The Journal of the Music Academy Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Applying Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning Techniques for Raga Recognition in Indian Classical Music

Applying Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning Techniques for Raga Recognition in Indian Classical Music Deepthi Peri Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science and Applications Eli Tilevich, Chair Sang Won Lee Eric Lyon August 6th, 2020 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Raga Recognition, ICM, MIR, Deep Learning Copyright 2020, Deepthi Peri Applying Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning Tech- niques for Raga Recognition in Indian Classical Music Deepthi Peri (ABSTRACT) In Indian Classical Music (ICM), the Raga is a musical piece’s melodic framework. It encom- passes the characteristics of a scale, a mode, and a tune, with none of them fully describing it, rendering the Raga a unique concept in ICM. The Raga provides musicians with a melodic fabric, within which all compositions and improvisations must take place. Identifying and categorizing the Raga is challenging due to its dynamism and complex structure as well as the polyphonic nature of ICM. Hence, Raga recognition—identify the constituent Raga in an audio file—has become an important problem in music informatics with several known prior approaches. Advancing the state of the art in Raga recognition paves the way to improving other Music Information Retrieval tasks in ICM, including transcribing notes automatically, recommending music, and organizing large databases. This thesis presents a novel melodic pattern-based approach to recognizing Ragas by representing this task as a document clas- sification problem, solved by applying a deep learning technique. A digital audio excerpt is hierarchically processed and split into subsequences and gamaka sequences to mimic a textual document structure, so our model can learn the resulting tonal and temporal se- quence patterns using a Recurrent Neural Network. -

M.A-Music-Vocal-Syllabus.Pdf

BANGALORE UNIVERSITY NAAC ACCREDITED WITH ‘A’ GRADE P.G. DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS JNANABHARATHI, BANGALORE-560056 MUSIC SYLLABUS – M.A KARNATAKA MUSIC VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL (VEENA, VIOLIN AND FLUTE) CBCS SYSTEM- 2014 Dr. B.M. Jayashree. Professor of Music Chairperson, BOS (PG) M.A. KARNATAKA MUSIC VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL (VEENA, VIOLIN AND FLUTE) Semester scheme syllabus CBCS Scheme of Examination, continuous Evaluation and other Requirements: 1. ELIGIBILITY: A Degree with music vocal/instrumental as one of the optional subject with at least 50% in the concerned optional subject an merit internal among these applicant Of A Graduate with minimum of 50% marks secured in the senior grade examination in music (vocal/instrumental) conducted by secondary education board of Karnataka OR a graduate with a minimum of 50% marks secured in PG Diploma or 2 years diploma or 4 year certificate course in vocal/instrumental music conducted either by any recognized Universities of any state out side Karnataka or central institution/Universities Any degree with: a) Any certificate course in music b) All India Radio/Doordarshan gradation c) Any diploma in music or five years of learning certificate by any veteran musician d) Entrance test (practical) is compulsory for admission. 2. M.A. MUSIC course consists of four semesters. 3. First semester will have three theory paper (core), three practical papers (core) and one practical paper (soft core). 4. Second semester will have three theory papers (core), two practical papers (core), one is project work/Dissertation practical paper and one is practical paper (soft core) 5. Third semester will have two theory papers (core), three practical papers (core) and one is open Elective Practical paper 6. -

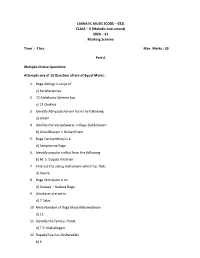

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

Dance Troupe

DANCE TROUPE The mission of our college ‘Blooming Humanity through Arts’ is disseminated by our institution through the program ‘Dance troupe’ globally for the past 39 years. It started on 27.12.1978 with the classical and folk dances of India and also dance dramas. The 1000th troupe programme was done on 13.01.2002 in the presence of the former Tamilnadu Chief-minister Dr.M.Kalaignar. It is also of great pride to say that soon the dance troupe will be performing its 3000thprogramme. KalaiKaviri performs dances not only to raga and thala but also performs dances with important didactic themes to reach the audience. Dances are performed with the following themes: Spirituality, Humanity, Social development, Moral values, Awareness, Religious morals and Patriotism. The troupe performs mainly in rural and remote areas to create awareness among the public. Irrespective of religion, caste and creed talented students from different backgrounds are selected, trained professionally for the troupe dances. This helps in the growth of the student’s individuality and also showcases their talent. The syllabus and dance items which students learn in their class are highly motivating for them to do a performance in the dance troupe. Main advantages of performing in a dance troupe include losing stage fear, sense of timing and rhythm, learning make-up techniques, costume selection and designing and helps building self-confidence in oneself. A student gets the opportunity to perform different roles and styles for example, classical, Indian folk and drama roles, hence by quick costume and role changes one’s concentration power increases. -

Andhra University 1 Year Diploma in (Music) Syllabus

SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATIN – ANDHRA UNIVERSITY 1st YEAR DIPLOMA IN (MUSIC) SYLLABUS (BOS approved and modified syllabus to be implemented from the admitted Batch 2012-13) Theory 100 Marks Paper I : Technical aspects of South Indian Classical Music 1. Technical Terms: a) Nada b) Sruti c) Swaras d) Swarasthanas e) Sathayi 2. Tala System: Sapta Talas, 35 Talas, Tala Dasa Prans, Chapu Tala Varieties Desadi and Madhyadi Talas 3. Musical Forms and their Lakshnas: Gitam, Varnam, Kritis, Kirtana, Padam, Ragamalika, Jasti Swaram, Swarajati, Tillana and Javali. 4. Lakshanas and Sancharas of the following Ragas: A a) Todi, b) Mayamalavagoula, c) Bhairavi, d) Kambhoji, e) Sankarabharanam f) Kalyani, g) Kharaharapriya, h) Mohana, i) Madhyamavathi j) Bilahari B. a) Dhanyasi, b) Saveri e)Vasanta d) HIndola e) Ananda Bhairavi f) Mukhari g) Kanada h) Khamas i) Begada j) Poorikalyani Paper II : Theoretical Aspects of South Indian Classical Music 100 Marks 1. Raaga and raga Lakshanam: a) Definition and Classification of ragas. b) Study of 13 Lakshanas c) ragalapana Padhathi 2. Musical Instruments and their classification 3. Special study of Tambura, Veena, Violin, Flute, Nagaswaram and Mridangam. 4. Characteristics of a composer. 5. Short biographical sketches of the following: a) Jayadeva b) Annamayya, c) Purandhara Dasa d) Narayana Tirtha e) Ramadasa f) Kshetrayya. Practical (First year) 100 Marks Paper III (Practical I) Fundamentals of Classical Music 1. a. Saraliswaras 6 b. Janta swaras 8 c. Alankaras 7 2. Gitas - 7 (Two Pillari Gitas, Two Ghanaraga Gitas, one Dhruva and one Lakshana gitam) 3. One Swarapallavi and one Swarajati 4. Five Adi Tala Varnas. -

108 Melodies

SRI SRI HARINAM SANKIRTAN - l08 MELODIES - INDEX CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1-2 Samant Sarang 37 Indian Classical Music Theory 3-13 Kurubh 38 Harinam Phylosphy & Development 14-15 Devagiri 39 FIRST PRAHAR RAGAS (6 A.M. to 9 A.M.) THIRD PRAHAR RAGAS (12 P.M. to 3 P.M.) Vairav 16 Gor Sarang 40 Bengal Valrav 17 Bhimpalasi 4 1 Ramkal~ 18 Piloo 42 B~bhas 19 Multani 43 Jog~a 20 Dhani 44 Tori 21 Triveni 45 Jaidev 22 Palasi 46 Morning Keertan 23 Hanskinkini 47 Prabhat Bhairav 24 FOURTH PKAHAR RAGAS (3 P.M. to 6 P.M.) Gunkali 25 Kalmgara 26 Traditional Keertan of Bengal 48-49 Dhanasari 50 SECOND PRAHAR RAGAS (9 A.M. to 12 P.M.) Manohar 5 1 Deva Gandhar 27 Ragasri 52 Bha~ravi 28 Puravi 53 M~shraBhairav~ 29 Malsri 54 Asavar~ 30 Malvi 55 JonPurl 3 1 Sr~tank 56 Durga (Bilawal That) 32 Hans Narayani 57 Gandhari 33 FIFTH PRAHAR RAGAS (6 P.M. to 9 P.M.) Mwa Bilawal 34 Bilawal 35 Yaman 58 Brindawani Sarang 36 Yaman Kalyan 59 Hem Kalyan 60 Purw Kalyan 61 Hindol Bahar 94 Bhupah 62 Arana Bahar 95 Pur~a 63 Kedar 64 SEVENTH PRAHAR RAGAS (12 A.M. to 3 A.M.) Jaldhar Kedar 65 Malgunj~ 96 Marwa 66 Darbar~Kanra 97 Chhaya 67 Basant Bahar 98 Khamaj 68 Deepak 99 Narayani 69 Basant 100 Durga (Khamaj Thhat) 70 Gaur~ 101 T~lakKarnod 71 Ch~traGaur~ 102 H~ndol 72 Shivaranjini 103 M~sraKhamaj 73 Ja~tsr~ 104 Nata 74 Dhawalsr~ 105 Ham~r 75 Paraj 106 Mall Gaura 107 SIXTH PRAHAR RAGAS (9Y.M. -

Bangalore for the Visitor

Bangalore For the Visitor PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 12 Dec 2011 08:58:04 UTC Contents Articles The City 11 BBaannggaalloorree 11 HHiissttoorryoofBB aann ggaalloorree 1188 KKaarrnnaattaakkaa 2233 KKaarrnnaattaakkaGGoovv eerrnnmmeenntt 4466 Geography 5151 LLaakkeesiinBB aanngg aalloorree 5511 HHeebbbbaalllaakkee 6611 SSaannkkeeyttaannkk 6644 MMaaddiiwwaallaLLaakkee 6677 Key Landmarks 6868 BBaannggaalloorreCCaann ttoonnmmeenntt 6688 BBaannggaalloorreFFoorrtt 7700 CCuubbbboonPPaarrkk 7711 LLaalBBaagghh 7777 Transportation 8282 BBaannggaalloorreMM eettrrooppoolliittaanTT rraannssppoorrtCC oorrppoorraattiioonn 8822 BBeennggaalluurruIInn tteerrnnaattiioonnaalAA iirrppoorrtt 8866 Culture 9595 Economy 9696 Notable people 9797 LLiisstoof ppee oopplleffrroo mBBaa nnggaalloorree 9977 Bangalore Brands 101 KKiinnggffiisshheerAAiirrll iinneess 110011 References AArrttiicclleSSoo uurrcceesaann dCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111155 IImmaaggeSS oouurrcceess,LL iicceennsseesaa nndCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111188 Article Licenses LLiicceennssee 112211 11 The City Bangalore Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Bangalore — — metropolitan city — — Clockwise from top: UB City, Infosys, Glass house at Lal Bagh, Vidhana Soudha, Shiva statue, Bagmane Tech Park Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Location of Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) in Karnataka and India Coordinates 12°58′′00″″N 77°34′′00″″EE Country India Region Bayaluseeme Bangalore 22 State Karnataka District(s) Bangalore Urban [1][1] Mayor Sharadamma [2][2] Commissioner Shankarlinge Gowda [3][3] Population 8425970 (3rd) (2011) •• Density •• 11371 /km22 (29451 /sq mi) [4][4] •• Metro •• 8499399 (5th) (2011) Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) [5][5] Area 741.0 square kilometres (286.1 sq mi) •• Elevation •• 920 metres (3020 ft) [6][6] Website Bengaluru ? Bangalore English pronunciation: / / ˈˈbæŋɡəɡəllɔəɔər, bæŋɡəˈllɔəɔər/, also called Bengaluru (Kannada: ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,, Bengaḷūru [[ˈˈbeŋɡəɭ uuːːru]ru] (( listen)) is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. -

The Journal of the Music Academy Madras Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

The Journal of Music Academy Madras ISSN. 0970-3101 Publication by THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar (Tamil) Part I, II & III each 150.00 Part – IV 50.00 Part – V 180.00 The Journal Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar of (English) Volume – I 750.00 Volume – II 900.00 The Music Academy Madras Volume – III 900.00 Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Volume – IV 650.00 Volume – V 750.00 Vol. 89 2018 Appendix (A & B) Veena Seshannavin Uruppadigal (in Tamil) 250.00 ŸÊ„¢U fl‚ÊÁ◊ flÒ∑ȧá∆U Ÿ ÿÊÁªNÔUŒÿ ⁄UflÊÒ– Ragas of Sangita Saramrta – T.V. Subba Rao & ◊jQÊ— ÿòÊ ªÊÿÁãà ÃòÊ ÁÃDÊÁ◊ ŸÊ⁄UŒH Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in English) 50.00 “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; Lakshana Gitas – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman 50.00 (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra The Chaturdandi Prakasika of Venkatamakhin 50.00 (Sanskrit Text with supplement) E Krishna Iyer Centenary Issue 25.00 Professor Sambamoorthy, the Visionary Musicologist 150.00 By Brahma EDITOR Sriram V. Raga Lakshanangal – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in Tamil) Volume – I, II & III each 150.00 VOL. 89 – 2018 VOL. COMPUPRINT • 2811 6768 Published by N. Murali on behalf The Music Academy Madras at New No. 168, TTK Road, Royapettah, Chennai 600 014 and Printed by N. Subramanian at Sudarsan Graphics Offset Press, 14, Neelakanta Metha Street, T. Nagar, Chennai 600 014. Editor : V. Sriram. THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS ISSN.