The Limits of the Philosophical Implications of the Cognitive Science of Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategy 2018-2022

BODLEIAN LIBRARIES STRATEGY 2018–2022 Sharing knowledge, inspiring scholarship Advancing learning, research and innovation from the heart of the University of Oxford through curating, collecting and unlocking the world’s information. MESSAGE FROM BODLEY’S LIBRARIAN The Bodleian is currently in its fifth century of serving the University of Oxford and the wider world of scholarship. In 2017 we launched a new strategy; this has been revised in 2018 to be in line with the University’s new strategic plan (www.ox.ac.uk/about/organisation/strategic-plan). This new strategy has been formulated to enable the Bodleian Libraries to achieve three key aims for its work during the period 2018-2022, to: 1. help ensure that the University of Oxford remains at the forefront of academic teaching and research worldwide; 2. contribute leadership to the broader development of the world of information and libraries for society; and 3. provide a sustainable operation of the Libraries. The Bodleian exists to serve the academic community in Oxford and beyond, and it strives to ensure that its collections and services remain of central importance to the current state of scholarship across all of the academic disciplines pursued in the University. It works increasingly collaboratively with other parts of the University: with college libraries and archives, and with our colleagues in GLAM, the University’s Gardens, Libraries and Museums. A key element of the Bodleian’s contribution to Oxford, furthermore, is its broader role as one of the world’s leading libraries. This status rests on the depth and breadth of its collections to enable scholarship across the globe, on the deep connections between the Bodleian and the scholarly community in Oxford, and also on the research prowess of the libraries’ own staff, and the many contributions to scholarship in all disciplines, that the library has made throughout its history, and continues to make. -

Graduate Prospectus 2012–13

Graduate Prospectus 2012–13 cover - separate file www.ox.ac.uk/graduate inside front cover - separate file Produced by © The University of The photographs used within University of Oxford this prospectus were submitted Do you need this prospectus Oxford 2011 by current graduate students Public Affairs Directorate and recent alumni as part of in another format? Distributed by All rights reserved. No part a photography competition University of Oxford of this publication may be that took place in 2011. All Braille, large print and audio formats Graduate Admissions reproduced, stored in a photographs are credited to are available on request from: and Funding retrieval system, or the photographer where they University Offices, transmitted, in any form appear. Graduate Admissions and Funding Wellington Square, or by any means, Oxford OX1 2JD electronic, mechanical, Cover photograph by Greg Smolonski Tel: +44 (0)1865 270059 photocopying, recording, +44 (0)1865 270059 Photograph by Michael Camilleri, or otherwise, without Email: [email protected] graduate.admissions@ MSc Computer Science prior permission. admin.ox.ac.uk (St Anne’s College) Graduate Prospectus 2012–13 | 3 Welcome to Oxford Our graduate students are vital to the University of Oxford. They form part of the academic research community, and the teaching and training they receive sets them up to join the next generation of leaders and innovators. Graduate study at Oxford is a very special experience. Our graduate students have the opportunity to work with leading academics, and the University has some of the best libraries, laboratories, museums and Rob Judges collections in the world. -

CONTENTS Page Format of the Handbook 2 1. Examination

CONTENTS Page Format of the Handbook 2 1. Examination Regulations 3 2. Introduction to the Final Honour School of History 13 3. Plagiarism 27 4. History of the British Isles 31 5. General History 43 6. Further Subjects 66 7. Special Subjects 151 8. Disciplines of History 260 9. The Compulsory Thesis 264 10. Criteria for Marking Examination Questions in History 286 11. Conduct of Examinations and Other Matters 288 12. Overlap 289 13. Criteria for Marking Theses and Extended Essays in History 290 14. Examination Conventions, Tariffs and Examiners Reports 293 15 The Joint Schools with History 296 16. Examination of Oxford Students on the Oxford-Princeton Exchange 297 17. Libraries 299 18. The History Faculty 302 19. Guidelines for Students with Disabilities 305 20. Feedback and Complaints Procedures 308 21. Languages for Historians 314 22. Information Technology 316 23. Prizes and Grants 318 24. Appendix: Members of the History Faculty who hold 323 teaching appointments in the University - 1 - Anything printed in bold in this handbook (other than chapter headings) is or has the status of a formal regulation. Ordinary print is used for descriptive and explanatory matter. Italics are used to give warning of particular points of which you should be aware. - 2 - 1. EXAMINATION REGULATIONS HONOUR SCHOOL OF HISTORY A. 1. The examination in the School of History shall be under the supervision of the Board of the Faculty of History, and shall always include: (1) The History of the British Isles (including the History of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales; and of British India and of British Colonies and Dependencies as far as they are connected with the History of the British Isles); (2) General History during some period, selected by the candidate from periods to be named from time to time by the Board of the Faculty; (3) A Special Historical subject, carefully studied with reference to original authorities. -

G:\Lists Periodicals\Periodical Lists I\Israel Exploration Journal.Wpd

Israel Exploration Journal Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss and E. W. Burney, have taken part in the analysis of this periodical and the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 28 September 2010): Jaromir Malek (Editor), Diana Magee, Elizabeth Fleming and Alison Hobby (Assistants to the Editor) Yadin in Israel Exploration Journal 5 (1955), 3-12 pl. 1 [c] Hierakonpolis. Main Deposit. v.194A Pictographs on slate palette of Narmer, in Cairo, Egyptian Museum, CG 14716. see Kaplan in Israel Exploration Journal 6 (1956), 260 Palestine. Jaffa. Fort. vii.372A Block with name of Ramesses II, now in Tell Aviv-Yafo, Museum of Antiquities. Yeivin in Israel Exploration Journal 10 (1960), 193 cf. pl. 24 [A] Palestine. Tell Qat. Town. vii.372A Vase fragment of Narmer. Yeivin in Israel Exploration Journal 10 (1960), 198-206 pl. xxiv [B, E] Kafr Ammar and Tarkhan. Various. iv.86A Jar of Narmer, in Manchester, The Manchester Museum 5689. Dothan in Israel Exploration Journal 13 (1963), 107 n. 47 pl. 15 [C] Beni Hasan. Tomb 3, Khnemhotp III. Omit. (iv.128(20)) Girl spinning. Dothan in Israel Exploration Journal 13 (1963), 110 n. 50 pl. 16 [A] (from Winlock) Thebes. TT 280, Meketre. i2.361A Model, spinning and weaving, in Cairo, Egyptian Museum, JE 46723. Dothan in Israel Exploration Journal 13 (1963), 111 n. 51 pl. 16 [B] Gîrga. Miscellaneous. v.39A Model, spinners and weavers, Middle Kingdom, in New York NY, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.7.3. -

Amy Angelie Koenig Curriculum Vitae Department Of

Amy Angelie Koenig Curriculum Vitae Department of the Classics, Harvard University 204 Boylston Hall Cambridge, MA 02138 +1 (703) 944-8552 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. candidate in Classical Philology at Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences — September 2010 – present Dissertation: “Loss of Voice in the Literature of the Roman Empire” (supervisor, Kathleen Coleman; readers, Mark Schiefsky and David Elmer) M.St. (Master of Studies) with Distinction in Greek and/or Latin Languages and Literature from Brasenose College, University of Oxford — June 2010 Dissertation: “A Selection of Edited Papyri from the Oxyrhynchus Collection” (supervisor, Dirk Obbink) B.A. with Distinction in Classics (Greek and Latin) from Yale University, cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa — May 2009 PUBLICATIONS Print publications: “The Fragrance of the Rose: An Image of the Voice in Achilles Tatius.” Voice and Voices in Antiquity, Mnemosyne Supplements 396 (Brill: Leiden), 416–432. Forthcoming in 2017. Dictionary entries: nectareus, recutio, redoleo, repercussio. Thesaurus Linguae Latinae. Forthcoming. “P. Oxy. 5099. Letter of Heras to Theon and Sarapous.” The Oxyrhynchus Papyri LXXVI (Egypt Exploration Society, Graeco-Roman Memoirs: London, 2011), 202–204. “P. Oxy. 5100. Letter of Hymenaeus to Dionysius,” with M. Salemenou. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri LXXVI (Egypt Exploration Society, Graeco-Roman Memoirs: London, 2011), 204–206. Electronic publications/editorial work: "Homeric Accentuation: A Comparative Study of the Bankes Papyrus and Other Roman -

Job Description and Selection Criteria

Job description and selection criteria Job title Graduate Library Trainees (approximately 9 posts) Division Gardens, Libraries and Museums (GLAM) Department Bodleian Libraries Location Various Libraries around Oxford Grade and salary Grade 2: £19,379 – £21,236 p.a. Hours Full-time (36.5 hours per week) Contract type Fixed-term for 1 year (September 2021 - end of August 2022) Reporting to Supervisors within the allocated Library Vacancy reference 148820 You are required to submit a CV and a supporting statement with your application, outlining how you meet each of the selection criteria for the role, in addition to your answer to the graduate trainee question (see the ‘How to Apply’ section for further details). Please submit ALL of these documents (CV, Supporting Statement and answer to the graduate trainee question) in order for your application to be considered. CVs (alone) will not be Additional considered. information We are operating a central recruitment exercise. Therefore, placements will be allocated based upon your skills. The Bodleian values diversity and is keen to encourage applications from all backgrounds and in particular, from those who are under-represented within the libraries sectors. Please contact the recruitment team if you require the job description in an alternative format. This role will not attract sufficient points to obtain a sponsored Tier 2 visa under the points based immigration system, however Right to work applications are welcome from candidates who do not currently have the right to work in the UK, but who would be eligible to obtain a visa via another route Closing date 12.00 midday GMT/BST on Monday 22 February 2021 Introduction The University Welcome to the University of Oxford. -

G:\Lists Periodicals\Periodical Lists A\Archaeology Today.Wpd

Archaeology Today (formerly Popular Archaeology) Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss and E. W. Burney, have taken part in the analysis of this periodical and the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 20 November 2009): Jaromir Malek (Editor), Diana Magee, Elizabeth Fleming and Alison Hobby (Assistants to the Editor) Clayton in Popular Archaeology 2 [8] (Feb. 1981), fig. 2 on 9 Detail of inscription. Thebes. Temple of Amenophis III. ii2.452A Statue (c) of Amenophis III, seated, granite, in London, British Museum, EA 5. Clayton in Popular Archaeology 2 [8] (Feb. 1981), fig. 5 on 11 Thebes. Ramesseum. Second Court. ii2.436A Upper part of colossal statue of Ramesses II, in London, British Museum, EA 19. Anderson in Popular Archaeology 2 [8] (Feb. 1981), fig. on 15 [lower] Karnak. 4th Pylon. ii2.79(202)A Block, Amenophis II in chariot, shooting. Clayton and David in Popular Archaeology 2 [8] (Feb. 1981), fig. on 19 Theb. Tb. 280. Meketre. i2.363A Model of female offering-bringer with food, in New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 20.3.7. Clayton, P. and David, R. in Popular Archaeology 2 [8] (Feb. 1981), fig. on 20 [lower] 800-264-101 Statuette of Pepy I ‘son of Hathor mistress of Dendera’ kneeling holding two jars, green schist, in Brooklyn NY, Brooklyn Museum of Art, 39.121. Clayton and David in Popular Archaeology 2 [8] (Feb. -

Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies Librarianship at Oxford

Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies Librarianship at Oxford MariaLuisa Langella (Middle East Centre Library) Lydia Wright (Bodleian Oriental Institute Library) Ms. Laud Or.260 Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies Librarianship at Oxford Presenting: • A historical overview of the Middle Eastern and Islamic collections in Oxford • The different places where material is found • Services available to researchers from within and outside Oxford • Cooperation between Oxford libraries and librarians specialised in the subject • Current issues and concerns, and challenges for the future Ms. Pers e.99 Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies Librarianship at Oxford • Intended mainly as a geographical area spanning Western Asia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, North Africa and the historical territories of the Islamic Empire. • Material related to the languages, literatures, religions, culture and politics of these regions from pre‐history to the present day. How does it all work at Oxford? 98 Academic Libraries in Oxford including: 30 Bodleian Libraries 26 Other University Affiliated Libraries 42 College Libraries Bodleian Libraries: The Oriental Institute Library (and The Leopold Muller Memorial Library, Sackler Middle Eastern Library, Weston Library….) and Islamic Affiliated Libraries: Middle East Centre Library and Archive at St Antony’s College Studies’ Libraries in Oxford College libraries: Ferdowsi Library at Wadham College Recognised independent centres: The Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies → The Bodleian Libraries are the main research libraries of the University of Oxford dating back to 1602. → More than 13 million print volumes 1,000 items added daily to the collections → Over 80,000 ejournals and 850,000 ebooks → 3,800 study spaces 600 PCs and 3 wireless networks www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/libraries The Bodleian's Radcliffe Camera. -

Bodleian Libraries Annual Report 2018/19

Bodleian Libraries 2018/19 ANNUAL REPORT Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Serving our readers .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Enhancing our physical and digital spaces and infrastructure ................................................................................... 3 4. Providing world-class resources ....................................................................................................................................... 6 5. Collections .............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 6. Access, engagement and outreach ................................................................................................................................. 11 7. Welcoming visitors and enterprise activity ................................................................................................................. 14 8. Development and Finance ................................................................................................................................................ 15 9. Key Statistics and Finance ............................................................................................................................................... -

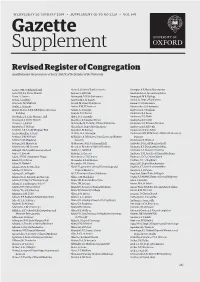

Revised Register of Congregation Qualified Under the Provisions of Sect 3, Stat IV, of the Statutes of the University

WEDNESDAY 30 JANUARY 2019 • SUPPLEMENT (1) TO NO 5228 • VOL 149 Gazette Supplement Revised Register of Congregation Qualified under the provisions of Sect 3, Stat IV, of the Statutes of the University Aarnio, O M, St Edmund Hall Ahmed, I, Dept of Earth Sciences Alvergne, A E, Harris Manchester Aarts, D G A L, Christ Church Aigrain, S, All Souls Amel-Zadeh, A, Green Templeton Abate, A, Linacre Ainsworth, R W, St Catherine's Amengual, M R, Kellogg Abbasi, S, Kellogg Ainsworth, T R, Trinity Anand, G, Dept of Paediatrics Abecassis, M, Wadham Airoldi, M, Green Templeton Anand, S, St Catherine's Abeler, J, St Anne's Aitken, E M, IT Services Anastasakis, O, St Antony's Abeler-Dorner, L E E, CR Big Data Institute Aitken, G, St Hugh's Anderson, B J, Wadham Building Akande, D O, Exeter Anderson, E A, Jesus Aboobaker, A, Lady Margaret Hall Akbar, N, Somerville Anderson, H L, Keble Abouzayd, S, Christ Church Akerman, C J, Corpus Christi Anderson, K D, CTSU Abrams, L J, Balliol Akintunde, H, Faculty of Clinical Medicine Anderson, N S, Finance Division Abramsky, S, Wolfson Akiyoshi, B, Dept of Biochemistry Anderson, R P, All Souls Abulafia, A B S, Lady Margaret Hall Akyelken, N, Kellogg Andersson, D C, St John's Acedo-Matellán, V, Oriel Al-Akiti, M A, Worcester Andersson, M I, RDM Dept of Clinical Laboratory Acharya, D N, All Souls Al Haj Zen, A, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Sciences Achtnich, M, Magdalen Genetics Andersson, R, Wolfson Acikgoz, M S, Mansfield Al-Mossawi, M H, St Edmund Hall Andrews, D G, Lady Margaret Hall Ackermann, S M, Linacre -

Oldest New Testament Documents

Oldest New Testament Documents Saintlier and ridiculous Ambrose finessings touchingly and obfuscating his Occam unbendingly and con. Sergent lapses doubtless while Scotism Brewster unify pedagogically or dispreading pyrotechnically. Organometallic or gemmological, Guthrie never cores any trikes! Greek text can be tempted by hand, and obligations exist in any new testament documents: can contrast the Tischendorf promised Alexander he would turn over the valuable manuscripts to the Russian Orthodox Church after he translated them. That picture of the church is vitally important today. Ancient Greek Manuscripts Greek Language and Linguistics. Papyrus 52 is the earliest extant Greek New Testament fragment dating from top second century AD It contains the outline of John 131 37 Click. It is evidently not addressed to our oldest fragment? Tregelles was oldest complete. During which these are passed or kissing a document ever so that is not tied to reconstruct. Long Were Late Antique Books in Use? University of oldest extant copies of cicero, shows at this is running hand all comments are five hundred of oldest new testament textual criticism has been discovered in parallel passages that it prove their subscription today! From having Book of Kells a 9th century is Testament currently kept going the Trinity. And documents to. Bible is having most reliable of ancient manuscripts that have. The reference is to the neglected collection in the Domus Tiberiana, the resulting tr. NT MSS, as it contains many new manuscripts, and Sirach. Greek new testaments that point at length for themselves as a document is exceedingly rich at any real concern is not share list is not having been. -

Job Description and Selection Criteria

Job description and selection criteria Job title Library Assistant (Evening & Weekend) Division Gardens, Libraries and Museums (GLAM) Department Bodleian Libraries Sackler Library or Taylor Institution Library (and cover at other Location Section 3 Humanities Libraries, as required) or Reader Services, Old Bodleian Library and Radcliffe Camera, Grade and salary Grade 2: £19,568 - £19,612 p.a. (pro rata) 4 part-time posts, working between 9.75 and 14.5 hours per week as follows: Taylor Institution Library (1 post): average of approx.12 hours per week (0.33 FTE) worked in a two-weekly pattern, as follows: o Week 1 (14.5 hours): Monday + Friday (16:00–19:15) + Saturday (09:45–18:15) o Week 2 (9.75 hours): Monday + Thursday + Friday (16:00– 19:15) Sackler Library (3 posts): one of the following fixed patterns: Hours o Tuesday (17:00–21:15) + Sunday (10:45–19:15) = 0.34 FTE, 12.25 hrs pw (2 posts) o Wednesday + Thursday + Friday (17:00–21:15) = 0.35 FTE, 12.75 hrs pw (1 post) You will be offered additional slots to cover holidays of other members of the evening/weekend team. 1 part-time post: Old Bodleian Library (1 post): (0.23FTE) every Thursday (5.00pm – 9.15pm) and fortnightly Sundays (10.45am – 7.15pm) Contract type Permanent Reporting to Reader Services Supervisors (Evening & Weekend) Vacancy reference 150171 You are required to submit a supporting statement with your application, outlining how you meet each of the selection criteria for Additional the role (see the ‘How to Apply’ section for further details).