The Medieval Period (1205-1540)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From South Hinksey Parish Plan Progress Report, April 2006

from www.southhinksey.co.uk South Hinksey Parish Plan Progress Report, April 2006 Action 1: Reduce A34 Probably the most requested action. This is constantly under road noise. discussion, with little success so far. Action 2: Improve safety The Parish Council now participate in the local transport group at slip-roads to with the police and neighbouring councils. The Chair of our A34 Parish Council has been very active in putting forward our concerns. Action 3: Reduce traffic New road markings on the Hill have not really solved the speed on Hinksey problem. Cats-eyes in the road have simply created a new Hill noise problem as large vehicles have to rumble over them. Action 4: Reduce the risk The Flood group has made progress with action taken by the of flooding railway authority to clear drain blockages and clearance of ditches and underground pipes in the village. In the last very heavy downpour there was no flooding in the village. Unfortunately the proposed bund around the village has been abandoned because the Environment Agency could not justify the high expenditure. Action 5: Improve and We have managed to get limited road repairs done in the repair roads, pavements village. Cutting back of overhanging hedges and removal of and footpaths litter particularly on Hinksey Hill has also been done. More pavement and road repairs are needed. Action 6: Improve parking Parking in the village has actually become more of a problem in the village since the pub car park has been fenced off. We are still working on this. Action 7: Upgrade bridge Network Rail have agreed to construct a "Wheelie ramp" on to New Hinksey to the Devil’s Backbone bridge improve cycle access Action 8: Create new We are working with Sustrans, the national cycle network, on cycling and walking establishing new cycle trails throughout the parish. -

Ttu Mac001 000057.Pdf (19.52Mb)

(Vlatthew flrnold. From the pn/ture in tlic Oriel Coll. Coniinon liooni, O.vford. Jhc Oxford poems 0[ attfiew ("Jk SAoUi: S'ips\i' ani "Jli\j«'vs.'') Illustrated, t© which are added w ith the storv of Ruskin's Roa(d makers. with Glides t© the Country the p©em5 iljystrate. Portrait, Ordnance Map, and 76 Photographs. by HENRY W. TAUNT, F.R.G.S. Photographer to the Oxford Architectural anid Historical Society. and Author of the well-knoi^rn Guides to the Thames. &c., 8cc. OXFORD: Henry W, Taunl ^ Co ALI. RIGHTS REStHVED. xji^i. TAONT & CO. ART PRINTERS. OXFORD The best of thanks is ren(iered by the Author to his many kind friends, -who by their information and assistance, have materially contributed to the successful completion of this little ^rork. To Mr. James Parker, -who has translated Edwi's Charter and besides has added notes of the greatest value, to Mr. Herbert Hurst for his details and additions and placing his collections in our hands; to Messrs Macmillan for the very courteous manner in which they smoothed the way for the use of Arnold's poems; to the Provost of Oriel Coll, for Arnold's portrait; to Mr. Madan of the Bodleian, for suggestions and notes, to the owners and occupiers of the various lands over which •we traversed to obtain some of the scenes; to the Vicar of New Hinksey for details, and to all who have helped with kindly advice, our best and many thanks are given. It is a pleasure when a ^ivork of this kind is being compiled to find so many kind friends ready to help. -

The Andrew Wiles Building: a Short History Below: Charles L

Nick Woodhouse The Andrew Wiles Building: A short history Below: Charles L. Dodgson A short time in the life of the University (Lewis Carroll) aged 24 at his “The opening of this desk [Wakeling Collection] The earliest ‘mathematical institute’ in Oxford fantastic building is may have been the School of Geometry and Arithmetic in the main Quadrangle of the great news for Oxford’s Bodleian Library (completed in 1620). But it was clearly insufficient to provide space staff and students, who for everyone. In 1649, a giant of Oxford mathematics, John Wallis, was elected to the will soon be learning Savilian Chair of Geometry. As a married man, he could not hold a college fellowship and he together in a stunning had no college rooms. He had to work from rented lodgings in New College Lane. new space.” In the 19th century, lectures were mainly given in colleges, prompting Charles Dodgson Rt Hon David Willets MP (Lewis Carroll) to write a whimsical letter to Minister of State for Universities and Science the Senior Censor of Christ Church. After commenting on the unwholesome nature of lobster sauce and the accompanying nightmares it can produce, he remarked: ‘This naturally brings me on to the subject of Mathematics, and of the accommodation provided by the University for carrying on the calculations necessary in that important branch of science.’ He continued with a detailed set of specifications, not all of which have been met even now. There was no room for the “narrow strip of ground, railed off and carefully levelled, for investigating the properties of Asymptotes, and testing practically whether Parallel Lines meet or not: for this purpose it should reach, to use the expressive language of Euclid, ‘ever so far’”. -

Council Letter Template

North Area Committee 4th March 2010 Central South and West Area Committee 9th March 2010 Strategic Development Control Committee 25th March 2010 Application Number: 09/02466/FUL, 09/02467/LBD, 09/02468/CAC Decision Due by: 10th February 2010 Proposal: 09/02466/FUL: Demolition of buildings on part of Acland site, retaining the main range of 25 Banbury Road, erection of 5 storey building fronting Banbury Road and 4 storey building fronting Woodstock Road to provide 240 student study bedrooms, 6 fellows flats, 3 visiting fellows flats with associated teaching office and research space and other ancillary facilities. Alteration to existing vehicular accesses to Banbury Road and Woodstock Road, provision of 27 parking spaces (including 4 disabled spaces) and 160 cycle parking spaces, recycling and waste bin storage, substation and including landscaping scheme. 09/02467/LBD: Listed Building Demolition. Demolition of buildings on part of Acland site, retaining the main range of 25 Banbury Road, (demolishing service range and later additions). Erection of extensions as part of a new college quad to provide 240 student study bedrooms, 6 fellows flats, 3 visiting fellows flats with associated teaching, office and research space and other ancillary facilities. External alterations including the removal of a chimney stack, underpinning and replacement of roof over staircase. Internal alterations to remove modern partitions, form new doorways, install en-suite facilities and reinstate staircase to 3rd floor. 09/02468/CAC: Conservation Area Consent. Demolition of 46 Woodstock Road. Site Address: Keble College Land At The Former Acland Hospital And 46 Woodstock Road 25 Banbury Road, (Site Plan - Appendix 1) Ward: North Agent: John Philips Planning Applicant: Keble College Consultancy REPORT Recommendation: Application for Planning Permission The North Area and Central South and West Area Committees are recommended to support the application for planning permission. -

REPORTS a Prehistoric Enclosure at Eynsham Abbey, Oxfordshire

REPORTS A Prehistoric Enclosure at Eynsham Abbey, Oxfordshire B) A 13 \RCI_~\, A 13m If and C.O. Ktf\lu. with contributions by A. BAYliS'>, C. BRO,\K Ibw,E1, T Ol RIl~,\, C. II \\ Ilf', J. ML L\ ILLf., P. ORIIIO\ f Rand E Rm SL i\IM.\R\ Part oj fl pr,hi\lnric ",rlm,,,.,. ditch U'(l\ e;vm'llltd Imor 10 Ilu' '.\/t'Il\lOU of Iht' grm't')"nd, of tlU' r/1IlJ(lit'\ oj St. Pt'tn\ mill St, LI'fJ1wrd\ E.lJl.\IUlm, O.t/orrN,i,.". I .nlr Rrtltlu- JIK' arttlarh u'rrt' jOlmd ;'llht lIppl'r Jt/t\ oj tlw (III(h Iml "L\ pn ....HUt that II U'flj (Q1uJru{/ed fllllln. ""IWI)' mill, Xfoli/hl(. UOPl~idt thl' lair 8m"ZI Igt' Ina/rna/, arltjar(\ oj StOWhl( and Bruhn/nat) 8wIIU' tw' datI' lL'f'I" (li\l) wl'ntified I pm."bll' lOlWdlw/HI' glllly. a l1wnhn oj /,i/\ and pm/lwft'\, mlll arl'W oj grmmd HlrjlICf. aI/ oj lalt 8r01l:..I' IKl'dalr ll'err joulld malIn IIIf' rnrlO\ll1f. Si.\ radu){mluJJI d(ltt,.~ tl'l'rt' obl/lllmi till mll/fnal dfrnmzgjl"Om til,. mrlo\llrt' ditch JiI/\ ami LIII' In""i~/{Jnr Kl'tul1Id ,\/irlflu, 11\ I ROIH ClIO~ hc Oxford Archaeological Unit (O.\l) eXGI\:~Ht'd an area of approximatel)' I HOOm.2 T \vilhill the Inner Ward or COUll of l-~y nsham .\boc) during 1990~92, The eXGI\,HIOnS were 1ll~\(lc nece:-.sall b) proposed cel11eter~ extensioll'i, and were \\holl) funded b) English Iledt4tgl'. -

Holy Trinity Church Parish Profile 2018

Holy Trinity Church Headington Quarry, Oxford Parish Profile 2018 www.hthq.uk Contents 4 Welcome to Holy Trinity 5 Who are we? 6 What we value 7 Our strengths and challenges 8 Our priorities 9 What we are looking for in our new incumbent 10 Our support teams 11 The parish 12 The church building 13 The churchyard 14 The Vicarage 15 The Coach House 16 The building project 17 Regular services 18 Other services and events 19 Who’s who 20 Congregation 22 Groups 23 Looking outwards 24 Finance 25 C. S. Lewis 26 Community and communications 28 A word from the Diocese 29 A word from the Deanery 30 Person specification 31 Role description 3 Welcome to Holy Trinity Thank you for looking at our Are you the person God is calling Parish Profile. to help us move forward as we seek to discover God’s plan and We’re a welcoming, friendly purposes for us? ‘to be an open door church on the edge of Oxford. between heaven and We’re known as the C. S. Lewis Our prayers are with you as you earth, showing God’s church, for this is where Lewis read this – please also pray for worshipped and is buried, and us. love to all’ we also describe ourselves as ’the village church in the city’, because that’s what we are. We are looking for a vicar who will walk with us on our Christian journey, unite us, encourage and enable us to grow and serve God in our daily lives in the parish and beyond. -

9-10 September 2017

9-10 September 2017 oxfordpreservation.org.uk Contents and Guide A B C D E F G A44 A34 To Birmingham (M40) 1 C 1 h d a To Worcester and Northampton (A43) oa d R n l to i Lin n g t B o a n P&R n R b o P&R Water Eaton W u a r d Pear o y N Contents Guide o R o & d Tree o r s d t a a o h t R o n d o m ns c awli k R o Page 2 Page 12 – Thursday 7 Sept – City centre map R o A40 o r a R Oxford To Cheltenham d o a 2 d 2 Page 4 – Welcome Page 13 – Friday 8 Sept W d oodst A40 Roa et’s r Banbur arga Page 5 – Highlights - Hidden Oxford Page 15 – Saturday 9 Sept M St ock R A34 y R oad M arst anal oad Page 7 Pages 20 & 21 To London (M40) – Highlights - Family Fun – OPT – what we do ace on R d C n Pl A40 W so or wn en Oxford a To B oad xf lt ark O P o City Page 8 Page 29 n ad – OPT venues – Sunday 10 Sept o S R d n a F P&R Centre oad t o o y P&R r d R fi e rn Seacourt a ad m e ondon R e F o a L Thornhill ry R h l t r 3 rbu No d 3 e R Page 9 t – OPT member only events an o C a d B r Botley Road e a rad d ad a m o th P k R Abingdon R r o No Cric A4142 r e I ffley R R Co o wley R a d s oad oad d n oad oa de R ar A420 rd G Red – OPT venues, FF – Family friendly, R – Refreshments available, D – Disabled access, fo am To Bristol ck rh Le No ad (D) – Partial disabled access Ro 4 ton P&R 4 ing Bev Redbridge A34 To Southampton For more specific information on disabled access to venues, please contact OPT or the venue. -

Wren and the English Baroque

What is English Baroque? • An architectural style promoted by Christopher Wren (1632-1723) that developed between the Great Fire (1666) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). It is associated with the new freedom of the Restoration following the Cromwell’s puritan restrictions and the Great Fire of London provided a blank canvas for architects. In France the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 revived religious conflict and caused many French Huguenot craftsmen to move to England. • In total Wren built 52 churches in London of which his most famous is St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711). Wren met Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in Paris in August 1665 and Wren’s later designs tempered the exuberant articulation of Bernini’s and Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture in Italy with the sober, strict classical architecture of Inigo Jones. • The first truly Baroque English country house was Chatsworth, started in 1687 and designed by William Talman. • The culmination of English Baroque came with Sir John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) and Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), Castle Howard (1699, flamboyant assemble of restless masses), Blenheim Palace (1705, vast belvederes of massed stone with curious finials), and Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight (now in ruins). Vanburgh’s final work was Seaton Delaval Hall (1718, unique in its structural audacity). Vanburgh was a Restoration playwright and the English Baroque is a theatrical creation. In the early 18th century the English Baroque went out of fashion. It was associated with Toryism, the Continent and Popery by the dominant Protestant Whig aristocracy. The Whig Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham, built a Baroque house in the 1720s but criticism resulted in the huge new Palladian building, Wentworth Woodhouse, we see today. -

The Record 2010 (Pdf)

Keble College Keble The Record 2010 The Record 2010 The Record 2010 Dame Professor Averil Cameron, Warden (1994–2010) Portrait by Bob Tulloch The Record 2010 Contents The Life of the College Letter from the Warden 5 College’s Farewell to the Warden 10 Sir David Williams 13 Mr Stephen De Rocfort Wall 15 Fellows’ Work in Progress 15 Fellows’ Publications 21 Sports and Games 25 Clubs and Societies 32 The Chapel 34 Financial Review 38 The College at Large Old Members at Work 42 Keble Parishes Update 48 Year Groups 49 Gifts and Bequests 51 Obituaries 63 The Keble Association 87 The London Dinner 88 Keble College 2009–10 The Fellowship 90 Fellowship Elections and Appointments 96 Recognition of Distinction 97 JCR & MCR Elections 97 Undergraduate Scholarships 97 Matriculation 2009–10 99 College Awards and Prizes 104 Academic Distinctions 109 Supplement News of Old Members 2 Forthcoming events: 2010–11 12 Keble College: The Record 2010 4 The Life of the College Letter from the Warden This is my sixteenth and last Letter as Warden, and obviously I write with many kinds of mixed feelings. Having had to move out of the Lodgings at the beginning instead of the end of the summer vacation, in order to allow time for necessary work to be done, I feel as if I am having an unusually prolonged retirement process, but the moment will come when the clock strikes midnight on 30 September and I cease to be Warden and Sir Jonathan Phillips takes over. The past sixteen years have been an extraordinarily rich experience, and I suspect that no one except another head of house really knows the full range of what is entailed. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

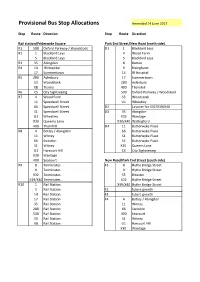

Provisional Bus Stop Allocations Amended 14 June 2017

Provisional Bus Stop Allocations Amended 14 June 2017 Stop Route Direction Stop Route Direction Rail station/Frideswide Square Park End Street/New Road (north side) R1 500 Oxford Parkway / Woodstock D1 1 Blackbird Leys R2 1 Blackbird Leys 4 Wood Farm 5 Blackbird Leys 5 Blackbird Leys R3 35 Abingdon 8 Barton R4 14 JR Hospital 9 Risinghurst 17 Summertown 14 JR Hospital R5 280 Aylesbury 17 Summertown S3 Woodstock 280 Aylesbury X8 Thame 400 Thornhill R6 CS City Sightseeing 500 Oxford Parkway / Woodstock R7 4 Wood Farm S3 Woodstock 11 Speedwell Street U1 Wheatley 66 Speedwell Street D2 Layover for X32/X39/X40 S1 Speedwell Street D3 35 Abingdon U1 Wheatley X32 Wantage X30 Queems Lane X39/X40 Wallingford 400 Thornhill D4 11 Butterwyke Place R8 4 Botley / Abingdon 66 Butterwyke Place 11 Witney S1 Butterwyke Place 66 Swindon S5 Butterwyke Place S1 Witney X30 Queens Lane U1 Harcourt Hill CS City Sightseeing X30 Wantage 400 Seacourt New Road/Park End Street (south side) R9 8 Terminates F1 8 Hythe Bridge Street 9 Terminates 9 Hythe Bridge Street X32 Terminates S5 Bicester X39/X40 Terminates X32 Hythe Bridge Street R10 1 Rail Station X39/X40 Hythe Bridge Street 5 Rail Station F2 future growth 14 Rail Station F3 future growth 17 Rail Station F4 4 Botley / Abingdon 35 Rail Station 11 Witney 280 Rail Station 66 Swindon 500 Rail Station 400 Seacourt S3 Rail Station S1 Witney X8 Rail Station U1 Harcourt Hill X30 Wantage Stop Route Direction Stop Route Direction Castle Street/Norfolk Street (west side) Castle Street/Norfolk Street (east side) E1 4 Botley -

Oriel College Record

Oriel College Record 2020 Oriel College Record 2020 A portrait of Saint John Henry Newman by Walter William Ouless Contents COLLEGE RECORD FEATURES The Provost, Fellows, Lecturers 6 Commemoration of Benefactors, Provost’s Notes 13 Sermon preached by the Treasurer 86 Treasurer’s Notes 19 The Canonisation of Chaplain’s Notes 22 John Henry Newman 90 Chapel Services 24 ‘Observing Narrowly’ – Preachers at Evensong 25 The Eighteenth Century World Development Director’s Notes 27 of Revd Gilbert White 92 Junior Common Room 28 How Does a Historian Start Middle Common Room 30 a New Book? She Goes Cycling! 95 New Members 2019-2020 32 Eugene Lee-Hamilton Prize 2020 100 Academic Record 2019-2020 40 Degrees and Examination Results 40 BOOK REVIEWS Awards and Prizes 48 Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, Leibniz: Graduate Scholars 48 Discourse on Metaphysics 104 Sports and Other Achievements 49 Robert Wainwright, Early Reformation College Library 51 Covenant Theology: English Outreach 53 Reception of Swiss Reformed Oriel Alumni Advisory Committee 55 Thought, 1520-1555 106 CLUBS, SOCIETIES NEWS AND ACTIVITIES Honours and Awards 110 Chapel Music 60 Fellows’ and Lecturers’ News 111 College Sports 63 Orielenses’ News 114 Tortoise Club 78 Obituaries 116 Oriel Women’s Network 80 Other Deaths notified since Oriel Alumni Golf 82 August 2019 135 DONORS TO ORIEL Provost’s Court 138 Raleigh Society 138 1326 Society 141 Tortoise Club Donors 143 Donors to Oriel During the Year 145 Diary 154 Notes 156 College Record 6 Oriel College Record 2020 VISITOR Her Majesty the Queen