Lymphoma in Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular Lymphoma What is follicular lymphoma? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMA: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of follicular lymphoma and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of follicular lymphoma. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the lead author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals, as well as two oncology nurses from the European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS). It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Follicular Lymphoma: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines – v.2014.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

Issue 53 • Fall/Winter 2015 Check out Our Fresh Newsletter Design!

AKC Canine Health Foundation Issue 53 • Fall/Winter 2015 THIS ISSUE AT A GLANCE Dr. Douglas Thamm Receives Asa Mays, DVM Award ............3 CHF Welcomes New CSO .........5 CHF & VetVine Team Up for Webinar Series ..........................6 Distinguished Research Partners to be Honored ........................... 7 2015 National Parent Club Canine Health Conference Recap ..........................................8 Labrador Retriever Club, Inc., to Receive President’s Award ....10 Cold Weather Canine Care ...10 Your Impact: Spontaneous Cancer in Dogs ........................13 Check out our fresh newsletter design! © Copyright 2015 AKC Canine Health Foundation. All rights reserved. Dear Canine Health Supporter: This year, we celebrate the 20th anniversary of the AKC Canine Health Foundation (CHF), a milestone that would not be possible without your commitment to the health of all dogs. Thanks to you, the dogs we love benefit from advances in veterinary medicine, receiving better treatment options and more accurate diagnoses for both common and complex health issues. From laying the groundwork that mapped the canine genome, to awarding grants that eventually led to genetic tests for conditions like Exercise-Induced Collapse and Von Willebrand’s Disease; from working collaboratively with researchers to bring about better understanding and more effective treatments for diseases like cancer, epilepsy and bloat, to being on the forefront of new, promising breakthroughs like stem cell research/regenerative medicine, anti-viral therapy and personalized medicine, your support of CHF has made these breakthroughs possible. As we look toward the future, your gift to CHF is as important as ever. By donating and continuing your commitment to canine health, you help build on the important scientific advances in veterinary medicine and biomedical science, impacting future generations of dogs. -

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Questions and Answers

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Questions and Answers What is Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma? Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a cancer of the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. When lymphocytes become cancerous (malignant), they multiply and become tumors. Lymphocytes are normally found in the blood stream and lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are found throughout the body and are identified by their location. They are a part of the body’s immune system, which includes the lymphatic system, spleen and lymphocytes. Some lymph nodes can be found just by feeling them in the neck, groin or under the arms. Some cannot be felt, but they can be seen on X-rays. NHL is the fifth most common cancer in the United States. Men are at slightly higher risk than women. It is more common in adults than children. The average age at diagnosis is 45 to 55 years. The cause of NHL remains unknown. What Are the Types and Symptoms of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma? There are more than 30 different types of NHL. The specific types of NHL are associated with different symptoms. Low-grade or indolent NHL is usually associated with painless swelling of lymph nodes (usually in the neck or over the collarbone), but patients are otherwise healthy. The swelling may go away for a while, but then return. If the low-grade NHL has spread outside of the lymph nodes, such as to the stomach, there may be discomfort in the affected area. Low-grade lymphomas grow slowly. Examples of low-grade NHLs include: Marginal zone lymphomas. -

Canine Breed Predisposition to Cancer

Canine Breed Predisposition to Cancer 1Amalia Saladrigas, 1Adrienne Thom, 2Amanda Koehne, DVM 1Stanford University (Class of 2016), 2Cancer Biology Program, Stanford School of Medicine Introduction Osteosarcoma: large breeds Lymphoma: Golden Retriever Particularly now that pets are living longer, cancer has become a leading 1 cause of death in dogs. Cancer can affect all breeds of dogs, but there are General Information: General Information: some breeds that appear to be at higher risk to certain types of cancer. • Most common primary bone tumor in dogs • Most common tumor of the hematopoietic system in dogs Given the similarities between many human and canine cancers, the domestic • The mean age is 7 years7 • Classification of canine lymphomas follows a similar classification 2 13 dog has been used as a model of spontaneous neoplasia. • It occurs in large and giant breed dogs: Doberman, German Shepherd, Golden scheme to that used for humans Retriever, Great Dane, Irish Setter, Rottweiler and Saint Bernard8 • Golden Retrievers are predisposed • Higher incidence in middle-aged dogs (6-7 years)14 Histiocytic Sarcoma: Bernese Clinical Manifestation: Mountain Dog • Occurs in the metaphysis of long bones, similar to disease in humans Clinical Manifestation: • Most common in proximal humerus, distal femur, and proximal tibia • Clinical signs are highly variable and reflect the organs involved General Information: • Metastasis usually to lungs and other bones • Lymphadenopathy, anorexia, and lethargy are common • Mean age of onset is 6.5 years -

MINI-REVIEW Large Cell Lymphoma Complicating Persistent Polyclonal B

Leukemia (1998) 12, 1026–1030 1998 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0887-6924/98 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/leu MINI-REVIEW Large cell lymphoma complicating persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis J Roy1, C Ryckman1, V Bernier2, R Whittom3 and R Delage1 1Division of Hematology, 2Department of Pathology, Saint Sacrement Hospital, 3Division of Hematology, CHUQ, Saint Franc¸ois d’Assise Hospital, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada Persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis (PPBL) is a rare immunoglobulin (Ig) M with a polyclonal pattern on protein lymphoproliferative disorder of unclear natural history and its electropheresis. Flow cytometry cell analysis displays the pres- potential for B cell malignancy remains unknown. We describe the case of a 39-year-old female who presented with stage IV- ence of the CD19 antigen and surface IgM with a normal B large cell lymphoma 19 years after an initial diagnosis of kappa/lambda ratio. In contrast to CLL, CD5 is absent. There PPBL; her disease was rapidly fatal despite intensive chemo- is an association between HLA-DR 7 and PPBL in more than therapy and blood stem cell transplantation. Because we had two-thirds of the patients but the reason for such an associ- recently identified multiple bcl-2/lg gene rearrangements in ation remains unclear.3,6 There has been one report of PPBL blood mononuclear cells of patients with PPBL, we sought evi- occurring in identical female twins.7 No other obvious genetic dence of this oncogene in this particular patient: bcl-2/lg gene rearrangements were found in blood mononuclear cells but not predisposition or familial inheritance has yet been described in lymphoma cells. -

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphoproliferative disorders Dr. Mansour Aljabry Definition Lymphoproliferative disorders Several clinical conditions in which lymphocytes are produced in excessive quantities ( Lymphocytosis) Lymphoma Malignant lymphoid mass involving the lymphoid tissues (± other tissues e.g : skin ,GIT ,CNS …) Lymphoid leukemia Malignant proliferation of lymphoid cells in Bone marrow and peripheral blood (± other tissues e.g : lymph nods ,spleen , skin ,GIT ,CNS …) Lymphoproliferative disorders Autoimmune Infection Malignant Lymphocytosis 1- Viral infection : •Infectious mononucleosis ,cytomegalovirus ,rubella, hepatitis, adenoviruses, varicella…. 2- Some bacterial infection: (Pertussis ,brucellosis …) 3-Immune : SLE , Allergic drug reactions 4- Other conditions:, splenectomy, dermatitis ,hyperthyroidism metastatic carcinoma….) 5- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) 6-Other lymphomas: Mantle cell lymphoma ,Hodgkin lymphoma… Infectious mononucleosis An acute, infectious disease, caused by Epstein-Barr virus and characterized by • fever • swollen lymph nodes (painful) • Sore throat, • atypical lymphocyte • Affect young people ( usually) Malignant Lymphoproliferative Disorders ALL CLL Lymphomas MM naïve B-lymphocytes Plasma Lymphoid cells progenitor T-lymphocytes AML Myeloproliferative disorders Hematopoietic Myeloid Neutrophils stem cell progenitor Eosinophils Basophils Monocytes Platelets Red cells Malignant Lymphoproliferative disorders Immature Mature ALL Lymphoma Lymphoid leukemia CLL Hairy cell leukemia Non Hodgkin lymphoma Hodgkin lymphoma T- prolymphocytic -

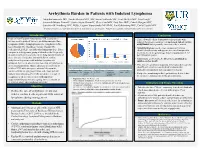

Arrhythmia Burden in Patients with Indolent Lymphoma

Arrhythmia Burden in Patients with Indolent Lymphoma Mujtaba Soniwala DO1, Saadia Sherazi MD1, MS, Susan Schleede MS1, Scott McNitt MS1, Tina Faugh2, Jeremiah Moore PharmD2, Justin Foster PharmD1, Clive Zent MD2, Paul Barr MD2, Patrick Reagan MD2, Jonathan W Friedberg MD2, MSSc, Eugene Storozynsky MD PhD1, Ilan Goldenberg MD1, Carla Casulo MD2 1Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry; 2Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester Medical Center Introduction Results Conclusions Indolent Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) comprise a • This real-world cohort demonstrates that patients with heterogeneous group of diseases including marginal zone indolent lymphoma could have an increased risk of cardiac lymphoma (MZL), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), arrhythmias that is possibly exacerbated by treatment. small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic • Atrial fibrillation was the most common arrhythmia leukemia (SLL/CLL), and follicular lymphoma (FL). These identified in this study and appears increased compared to compose a heterogenous group of disorders that frequently the incidence in the general age matched population (1-1.8 measures survival in years due to the long natural history of per 100 person-years). these diseases. Frequency and morbidity of cardiac • Surprisingly, of 80 deaths, 8 (10%) were attributed to arrhythmias in patients with indolent lymphoma is Arrhythmia Incidence Subtype of Indolent Lymphoma sudden cardiac death. unknown, but recent observations note that arrhythmias are • This data set contributes important information that can help an increasing problem. Due to advances in treatment for Arrhythmia incidence by CLL = 89 (53%) FL = 35 (21%) MZL = 27 (16%) LPL = 17 (10%) lymphoma subtype of total identify patients at increased risk of cardiovascular indolent NHL with emergence of novel therapeutics, (N = 168) Arrhythmia incidence Combination Targeted Therapy = Monoclonal Chemotherapy morbidity and mortality that can impact treatment. -

Understanding Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/ Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

Understanding Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/ Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that arise from B lymphocytes. CLL and SLL are essentially the same disease, with the only difference being the location where the cancer primarily occurs. When most of the cancer cells are located in the bloodstream and the bone marrow, the disease is referred to as CLL, although the lymph nodes and spleen are often involved. When the cancer cells are located mostly in the lymph nodes and are less frequent in the blood, the disease is called SLL. Many patients with CLL/SLL do not have any obvious symptoms of the disease. Their doctors might detect the disease during routine blood tests and/or a physical examination. For others, the disease is detected when symptoms occur and the patient goes to the doctor because he or she is worried, uncomfortable, or does not feel well. CLL/SLL may cause different symptoms depending on the location of the tumor in the body, including fatigue (extreme tiredness), shortness of breath, anemia (low red blood cell count), bruising easily, night sweats, weight loss, frequent infections. Other symptoms can include a swollen abdomen and feeling full even after eating only a small amount. However, many patients with CLL/SLL will live for years without symptoms. TREATMENT OPTIONS • Chlorambucil (Leukeran) and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) • Venetoclax (Venclexta) and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) Treatment is based on the severity of associated symptoms Occasionally patients might also be treated with chemotherapy, as well as the rate of cancer growth. -

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’S Lymphomas Version 2.2015

NCCN Guidelines Index NHL Table of Contents Discussion NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas Version 2.2015 NCCN.org Continue Version 2.2015, 03/03/15 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2015, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN® . Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2015 NCCN Guidelines Index NHL Table of Contents Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas Discussion DIAGNOSIS SUBTYPES ESSENTIAL: · Review of all slides with at least one paraffin block representative of the tumor should be done by a hematopathologist with expertise in the diagnosis of PTCL. Rebiopsy if consult material is nondiagnostic. · An FNA alone is not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Subtypes included: · Adequate immunophenotyping to establish diagnosisa,b · Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), NOS > IHC panel: CD20, CD3, CD10, BCL6, Ki-67, CD5, CD30, CD2, · Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL)d See Workup CD4, CD8, CD7, CD56, CD57 CD21, CD23, EBER-ISH, ALK · Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), ALK positive (TCEL-2) or · ALCL, ALK negative > Cell surface marker analysis by flow cytometry: · Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) kappa/lambda, CD45, CD3, CD5, CD19, CD10, CD20, CD30, CD4, CD8, CD7, CD2; TCRαβ; TCRγ Subtypesnot included: · Primary cutaneous ALCL USEFUL UNDER CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES: · All other T-cell lymphomas · Molecular analysis to detect: antigen receptor gene rearrangements; t(2;5) and variants · Additional immunohistochemical studies to establish Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (See NKTL-1) lymphoma subtype:βγ F1, TCR-C M1, CD279/PD1, CXCL-13 · Cytogenetics to establish clonality · Assessment of HTLV-1c serology in at-risk populations. -

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL)

Helpline (freephone) 0808 808 5555 [email protected] www.lymphoma-action.org.uk Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) This information is about chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). CLL and SLL are different forms of the same illness. They are often grouped together as a type of slow-growing (low-grade or indolent) non-Hodgkin lymphoma. On this page What is CLL/SLL? Who gets CLL? Symptoms of CLL Diagnosis and staging Outlook Treatment Follow-up Relapsed or refractory CLL Research and targeted treatments We have separate information about the topics in bold font. Please get in touch if you’d like to request copies or if you would like further information about any aspect of lymphoma. Phone 0808 808 5555 or email [email protected]. Page 1 of 13 © Lymphoma Action What is CLL/SLL? Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are slow-growing types of blood cancer. They develop when white blood cells called lymphocytes grow out of control. Lymphocytes are part of your immune system. They travel around your body in your lymphatic system, helping you fight infections. There are two types of lymphocyte: T lymphocytes (T cells) and B lymphocytes (B cells). CLL and SLL are different forms of the same illness. They develop when B cells that don’t work properly build up in your body. • In CLL, the abnormal B cells build up in your blood and bone marrow. This is why it’s called ‘leukaemia’ – after ‘leucocytes’: the medical name for white blood cells. -

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Rick, non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivor This publication was supported in part by grants from Revised 2013 A Message From John Walter President and CEO of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) believes we are living at an extraordinary moment. LLS is committed to bringing you the most up-to-date blood cancer information. We know how important it is for you to have an accurate understanding of your diagnosis, treatment and support options. An important part of our mission is bringing you the latest information about advances in treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, so you can work with your healthcare team to determine the best options for the best outcomes. Our vision is that one day the great majority of people who have been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma will be cured or will be able to manage their disease with a good quality of life. We hope that the information in this publication will help you along your journey. LLS is the world’s largest voluntary health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research, education and patient services. Since 1954, LLS has been a driving force behind almost every treatment breakthrough for patients with blood cancers, and we have awarded almost $1 billion to fund blood cancer research. Our commitment to pioneering science has contributed to an unprecedented rise in survival rates for people with many different blood cancers. Until there is a cure, LLS will continue to invest in research, patient support programs and services that improve the quality of life for patients and families. -

Analysis of Inherited and Somatic Variants to Decipher Canine Complex Traits

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1454 Analysis of inherited and somatic variants to decipher canine complex traits KATE MEGQUIER ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 ISBN 978-91-513-0310-9 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-347165 2018 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in B:22, BMC, Husargatan 3, Uppsala, Monday, 21 May 2018 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine). The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: David Sargan (University of Cambridge). Abstract Megquier, K. 2018. Analysis of inherited and somatic variants to decipher canine complex traits. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1454. 67 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0310-9. This thesis presents several investigations of the dog as a model for complex diseases, focusing on cancers and the effect of genetic risk factors on clinical presentation. In Papers I and II, we performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify germline risk factors predisposing US golden retrievers to hemangiosarcoma (HSA) and B- cell lymphoma (BLSA). Paper I identified two loci predisposing to both HSA and BLSA, approximately 4 megabases (Mb) apart on chromosome 5. Carrying the risk haplotype at these loci was associated with separate changes in gene expression, both relating to T-cell activation and proliferation. Paper II followed up on the HSA GWAS by performing a meta-analysis with additional cases and controls. This confirmed three previously reported GWAS loci for HSA and revealed three new loci, the most significant on chromosome 18.