The Khobar Towers Bombing Incident

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country City Sitename Street Name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St

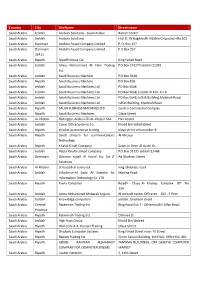

Country City SiteName Street name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St. W.Bogddadih AlZabin Cmpound villa 102 Saudi Arabia Damman Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P. O. Box 257 Saudi Arabia Dammam Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P O Box 257 31411 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Riyadh House Est. King Fahad Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Idress Mohammed Ali Fatni Trading P.O.Box 132270 Jeddah 21382 Est. Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machine P.O.Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machine P.O Box 818 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd PO Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Jeddah 21432, K S A Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Juffali Building,Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. Juffali Building, Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Riyadh SAUDI BUSINESS MACHINES LTD. Centria Commercial Complex Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machines Olaya Street Saudi Arabia Al-Khobar Redington Arabia LTD AL-Khobar KSA Hail Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Canar Office Systems Co Khalid Bin Walid Street Saudi Arabia Riyadh shrakat partnerships trading olaya street villa number 8 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Unicom for communications Al-Mrouje technology Saudi Arabia Riyadh Khalid Al Safi Company Salah Al-Deen Al-Ayubi St., Saudi Arabia Jeddah Azizia Panda United Company P.O.Box 33333 Jeddah 21448 Saudi Arabia Dammam Othman Yousif Al Yousif Est. for IT Ad Dhahran Street Solutions Saudi Arabia Al Khober al hasoob al asiavy est. king abdulaziz road Saudi Arabia Jeddah EchoServe-Al Sada Al Shamila for Madina Road Information Technology Co. -

Hezbollah's Syrian Quagmire

Hezbollah’s Syrian Quagmire BY MATTHEW LEVITT ezbollah – Lebanon’s Party of God – is many things. It is one of the dominant political parties in Lebanon, as well as a social and religious movement catering first and fore- Hmost (though not exclusively) to Lebanon’s Shi’a community. Hezbollah is also Lebanon’s largest militia, the only one to maintain its weapons and rebrand its armed elements as an “Islamic resistance” in response to the terms of the Taif Accord, which ended Lebanon’s civil war and called for all militias to disarm.1 While the various wings of the group are intended to complement one another, the reality is often messier. In part, that has to do with compartmen- talization of the group’s covert activities. But it is also a factor of the group’s multiple identities – Lebanese, pan-Shi’a, pro-Iranian – and the group’s multiple and sometimes competing goals tied to these different identities. Hezbollah insists that it is Lebanese first, but in fact, it is an organization that always acts out of its self-interests above its purported Lebanese interests. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, Hezbollah also has an “expansive global network” that “is sending money and operatives to carry out terrorist attacks around the world.”2 Over the past few years, a series of events has exposed some of Hezbollah’s covert and militant enterprises in the region and around the world, challenging the group’s standing at home and abroad. Hezbollah operatives have been indicted for the murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri by the UN Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) in The Hague,3 arrested on charges of plotting attacks in Nigeria,4 and convicted on similar charges in Thailand and Cyprus.5 Hezbollah’s criminal enterprises, including drug running and money laundering from South America to Africa to the Middle East, have been targeted by law enforcement and regulatory agen- cies. -

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

White Paper Makkah | Retail 2018 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Evolving Dynamics Makkah Retail Overview Summary The holy city of Makkah is currently going through a major strategic development phase to improve connectivity, Ian Albert increase capacity, and enhance the experience of Umrah Regional Director and Hajj pilgrims throughout their stay. Middle East & North Africa This is reflected in the execution of several strategic infrastructure and transportation projects, which have a clear focus on increasing pilgrim capacity and improving connectivity with key projects, including the Holy Haram Expansion, Haramain High- Speed Railway, and King Abdulaziz International Airport. These projects, alongside Vision 2030, are shaping the city’s real estate landscape and stimulating the development of several large real estate projects in their surrounding areas, including King Abdulaziz Road (KAAR), Jabal Omar, Thakher City and Ru’a Al Haram. These projects are creating opportunities for the development of various retail Imad Damrah formats that target pilgrims. Managing Director | Saudi Arabia Makkah has the lowest retail density relative to other primary cities; Riyadh, Jeddah, Dammam Al Khobar and Madinah. With a retail density of c.140 sqm / 1,000 population this is 32% below Madinah which shares the same demographics profile. Upon completion of major transport infrastructure and real estate projects the number of pilgrims is projected to grow by almost 223% from 12.1 million in 2017 up to 39.1 million in 2030 in line with Vision 2030 targets. Importantly the majority of international Pilgrims originate from countries with low purchasing power. Approximately 59% of Hajj and Umrah pilgrims come from countries with GDP/capita below USD 5,000 (equivalent to SAR 18,750). -

The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 7: The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The Ministry for Islamic Affairs, Endowments, Da’wah, and Guidance, commonly abbreviated to the Ministry of Islamic Affairs (MOIA), supervises and regulates religious activity in Saudi Arabia. Whereas the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) directly enforces religious law, as seen in Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 1,1 the MOIA is responsible for the administration of broader religious services. According to the MOIA, its primary duties include overseeing the coordination of Islamic societies and organizations, the appointment of clergy, and the maintenance and construction of mosques.2 Yet, despite its official mission to “preserve Islamic values” and protect mosques “in a manner that fits their sacred status,”3 the MOIA is complicit in a longstanding government campaign against the peninsula’s traditional heritage – Islamic or otherwise. Since 1925, the Al Saud family has overseen the destruction of tombs, mosques, and historical artifacts in Jeddah, Medina, Mecca, al-Khobar, Awamiyah, and Jabal al-Uhud. According to the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, between just 1985 and 2014 – through the MOIA’s founding in 1993 –the government demolished 98% of the religious and historical sites located in Saudi Arabia.4 The MOIA’s seemingly contradictory role in the destruction of Islamic holy places, commentators suggest, is actually the byproduct of an equally incongruous alliance between the forces of Wahhabism and commercialism.5 Compelled to acknowledge larger demographic and economic trends in Saudi Arabia – rapid population growth, increased urbanization, and declining oil revenues chief among them6 – the government has increasingly worked to satisfy both the Wahhabi religious establishment and the kingdom’s financial elite. -

Iran's Gray Zone Strategy

Iran’s Gray Zone Strategy Cornerstone of its Asymmetric Way of War By Michael Eisenstadt* ince the creation of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Iran has distinguished itself (along with Russia and China) as one of the world’s foremost “gray zone” actors.1 For nearly four decades, however, the United States has struggled to respond effectively to this asymmetric “way of war.” Washington has often Streated Tehran with caution and granted it significant leeway in the conduct of its gray zone activities due to fears that U.S. pushback would lead to “all-out” war—fears that the Islamic Republic actively encourages. Yet, the very purpose of this modus operandi is to enable Iran to pursue its interests and advance its anti-status quo agenda while avoiding escalation that could lead to a wider conflict. Because of the potentially high costs of war—especially in a proliferated world—gray zone conflicts are likely to become increasingly common in the years to come. For this reason, it is more important than ever for the United States to understand the logic underpinning these types of activities, in all their manifestations. Gray Zone, Asymmetric, and Hybrid “Ways of War” in Iran’s Strategy Gray zone warfare, asymmetric warfare, and hybrid warfare are terms that are often used interchangeably, but they refer neither to discrete forms of warfare, nor should they be used interchangeably—as they often (incor- rectly) are. Rather, these terms refer to that aspect of strategy that concerns how states employ ways and means to achieve national security policy ends.2 Means refer to the diplomatic, informational, military, economic, and cyber instruments of national power; ways describe how these means are employed to achieve the ends of strategy. -

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

Surprise, Intelligence Failure, and Mass Casualty Terrorism

SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM by Thomas E. Copeland B.A. Political Science, Geneva College, 1991 M.P.I.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1992 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Thomas E. Copeland It was defended on April 12, 2006 and approved by Davis Bobrow, Ph.D. Donald Goldstein, Ph.D. Dennis Gormley Phil Williams, Ph.D. Dissertation Director ii © 2006 Thomas E. Copeland iii SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM Thomas E. Copeland, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This study aims to evaluate whether surprise and intelligence failure leading to mass casualty terrorism are inevitable. It explores the extent to which four factors – failures of public policy leadership, analytical challenges, organizational obstacles, and the inherent problems of warning information – contribute to intelligence failure. This study applies existing theories of surprise and intelligence failure to case studies of five mass casualty terrorism incidents: World Trade Center 1993; Oklahoma City 1995; Khobar Towers 1996; East African Embassies 1998; and September 11, 2001. A structured, focused comparison of the cases is made using a set of thirteen probing questions based on the factors above. The study concludes that while all four factors were influential, failures of public policy leadership contributed directly to surprise. Psychological bias and poor threat assessments prohibited policy makers from anticipating or preventing attacks. Policy makers mistakenly continued to use a law enforcement approach to handling terrorism, and failed to provide adequate funding, guidance, and oversight of the intelligence community. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

Iran, Terrorism, and Weapons of Mass Destruction

Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 31:169–181, 2008 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1057-610X print / 1521-0731 online DOI: 10.1080/10576100701878424 Iran, Terrorism, and Weapons of Mass Destruction DANIEL BYMAN Center for Peace and Security Studies Georgetown University Washington, DC, USA and Saban Center for Middle East Policy Brookings Institution Washington, DC, USA This article reviews Iran’s past and current use of terrorism and assesses why U.S. attempts to halt Iran’s efforts have met with little success. With this assessment in mind, it argues that Iran is not likely transfer chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons to terrorist groups for several reasons. First, providing terrorists with such unconventional Downloaded By: [Georgetown University] At: 15:20 19 March 2008 weapons offers Iran few tactical advantages as these groups are able to operate effectively with existing methods and weapons. Second, Iran has become more cautious in its backing of terrorists in recent years. And third, Tehran is highly aware that any major escalation in its support for terrorism would incur U.S. wrath and international condemnation. The article concludes by offering recommendations for decreasing Iran’s support for terrorism. Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iran has been one of the world’s most active sponsors of terrorism. Tehran has armed, trained, financed, inspired, organized, and otherwise supported dozens of violent groups over the years.1 Iran has backed not only groups in its Persian Gulf neighborhood, but also terrorists and radicals in Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Bosnia, the Philippines, and elsewhere.2 This support remains strong even today: the U.S. -

U.S. Military Engagement in the Broader Middle East

U.S. MILITARY ENGAGEMENT IN THE BROADER MIDDLE EAST JAMES F. JEFFREY MICHAEL EISENSTADT U.S. MILITARY ENGAGEMENT IN THE BROADER MIDDLE EAST JAMES F. JEFFREY MICHAEL EISENSTADT THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY WWW.WASHINGTONINSTITUTE.ORG The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. Policy Focus 143, April 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing fromthe publisher. ©2016 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1111 19th Street NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: An F-16 from the Egyptian Air Force prepares to make contact with a KC-135 from the 336th ARS during in-flight refueling training. (USAF photo by Staff Sgt. Amy Abbott) Contents Acknowledgments V I. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF U.S. MILITARY OPERATIONS 1 James F. Jeffrey 1. Introduction to Part I 3 2. Basic Principles 5 3. U.S. Strategy in the Middle East 8 4. U.S. Military Engagement 19 5. Conclusion 37 Notes, Part I 39 II. RETHINKING U.S. MILITARY STRATEGY 47 Michael Eisenstadt 6. Introduction to Part II 49 7. American Sisyphus: Impact of the Middle Eastern Operational Environment 52 8. Disjointed Strategy: Aligning Ways, Means, and Ends 58 9. -

Hizbullah Under Fire in Syria | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Hizbullah Under Fire in Syria by Matthew Levitt, Nadav Pollak Jun 9, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Matthew Levitt Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute. Nadav Pollak Nadav Pollak is a former Diane and Guilford Glazer Foundation fellow at The Washington Institute. Articles & Testimony Last month's assassination of a senior Hizbullah commander, apparently by Syrian rebel groups, demonstrates the growing threat the organization faces from fellow Arabs and Muslims. he death of senior Hizbullah commander Mustafa Badreddine in Syria in May left the group reeling, but not for T the reason most people think. True, it lost an especially qualified commander with a unique pedigree as the brother-in-law of Imad Mughniyeh, with whom Badreddine plotted devastating terror attacks going back to the Beirut bombings in the 1980s. And, at the time of his death, Badreddine was dual-hatted as the commander of both the group's international terrorist network (the Islamic Jihad Organisation or External Security Organisation) and its significant military deployment in Syria. The loss of such a senior and seasoned commander is no small setback for Hizbullah. But the real reason Badreddine's death has Hizbullah on edge is not the loss of the man, per se, but the fact that the group's arch enemy, Israel, was seemingly not responsible. Hizbullah, it appears, now has more immediate enemies than Israel -- and that has the self-described "resistance" organisation tied up in knots. -

Indo-Saudia Trade of Traditional and Non-Traditional Items

INDO-SAUDIA TRADE OF TRADITIONAL AND NON-TRADITIONAL ITEMS DIS^ERT\TION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION BY ADIL PERVAIZ UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. ASIF HALEEM Reader DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1981 \98l 1A c: HI mi DS479 CEECZrD.2ooa >/^ DEPTT. OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) ASIF HALEEM Reader June 15<, 1982 This is to certify that Mr, Adil Pervaiz is a bonafide student of M.B.A. and has done his dissertation entitled "INDO - SAUDI A TRADE OF TRADITIONAL AND NON-TRADITIONAL ITEMS" under my supervision, in partial fulfil ment for the award of the degree of Master of Business Administr ation. As far as I know his work is original and has never been s\d:»nitted here or elsewhere for the award of any other degree. ( ASIF EEM ) ERVISOR CONTENTS PAGE NO. PREFACE PART - I SAUDI ARABIA CHAPTER 1 Economy ; 1 CHAPTER 2 Market Structure 32 CHAPTER 3 Trade -Policy and Relevant Laws, Segulations and Procedures. 47 CHAPTER - 4 Foreign Trade and Balance of Payments 55 PART - II INDIA CHAPTER -- 5 • Economy 66 CHAPTER -- 6 • Foreign Trade .78 PART - III TRADE CHAPTER -- 7 • India's Trade with Saudi Arabia 91 CHAPTER - 8 : Findings and Recommendations 131 APPENDICES; Appendix - I 137 Appendix - II 142 Appendix - III 150 BIBLIOGRAPHY 156 *-)«•****-***•)(• PREFACE After the independence, India established good relations with the Arab coiintries. However, trade between India and the Arab rforld was limited to few traditional items which were in abundance in India, moreover, in the Arab World the only country which had potential for growth and trade was -Sgypt (U.A.R.)' Thus most of the trade was limited to Egypt.