Islamic Extremism in Saudi Arabia and the Attack on Al Khobar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

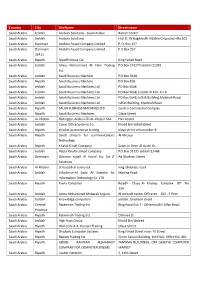

Country City Sitename Street Name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St

Country City SiteName Street name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St. W.Bogddadih AlZabin Cmpound villa 102 Saudi Arabia Damman Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P. O. Box 257 Saudi Arabia Dammam Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P O Box 257 31411 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Riyadh House Est. King Fahad Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Idress Mohammed Ali Fatni Trading P.O.Box 132270 Jeddah 21382 Est. Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machine P.O.Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machine P.O Box 818 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd PO Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Jeddah 21432, K S A Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Juffali Building,Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. Juffali Building, Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Riyadh SAUDI BUSINESS MACHINES LTD. Centria Commercial Complex Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machines Olaya Street Saudi Arabia Al-Khobar Redington Arabia LTD AL-Khobar KSA Hail Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Canar Office Systems Co Khalid Bin Walid Street Saudi Arabia Riyadh shrakat partnerships trading olaya street villa number 8 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Unicom for communications Al-Mrouje technology Saudi Arabia Riyadh Khalid Al Safi Company Salah Al-Deen Al-Ayubi St., Saudi Arabia Jeddah Azizia Panda United Company P.O.Box 33333 Jeddah 21448 Saudi Arabia Dammam Othman Yousif Al Yousif Est. for IT Ad Dhahran Street Solutions Saudi Arabia Al Khober al hasoob al asiavy est. king abdulaziz road Saudi Arabia Jeddah EchoServe-Al Sada Al Shamila for Madina Road Information Technology Co. -

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

White Paper Makkah | Retail 2018 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Evolving Dynamics Makkah Retail Overview Summary The holy city of Makkah is currently going through a major strategic development phase to improve connectivity, Ian Albert increase capacity, and enhance the experience of Umrah Regional Director and Hajj pilgrims throughout their stay. Middle East & North Africa This is reflected in the execution of several strategic infrastructure and transportation projects, which have a clear focus on increasing pilgrim capacity and improving connectivity with key projects, including the Holy Haram Expansion, Haramain High- Speed Railway, and King Abdulaziz International Airport. These projects, alongside Vision 2030, are shaping the city’s real estate landscape and stimulating the development of several large real estate projects in their surrounding areas, including King Abdulaziz Road (KAAR), Jabal Omar, Thakher City and Ru’a Al Haram. These projects are creating opportunities for the development of various retail Imad Damrah formats that target pilgrims. Managing Director | Saudi Arabia Makkah has the lowest retail density relative to other primary cities; Riyadh, Jeddah, Dammam Al Khobar and Madinah. With a retail density of c.140 sqm / 1,000 population this is 32% below Madinah which shares the same demographics profile. Upon completion of major transport infrastructure and real estate projects the number of pilgrims is projected to grow by almost 223% from 12.1 million in 2017 up to 39.1 million in 2030 in line with Vision 2030 targets. Importantly the majority of international Pilgrims originate from countries with low purchasing power. Approximately 59% of Hajj and Umrah pilgrims come from countries with GDP/capita below USD 5,000 (equivalent to SAR 18,750). -

The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 7: The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The Ministry for Islamic Affairs, Endowments, Da’wah, and Guidance, commonly abbreviated to the Ministry of Islamic Affairs (MOIA), supervises and regulates religious activity in Saudi Arabia. Whereas the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) directly enforces religious law, as seen in Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 1,1 the MOIA is responsible for the administration of broader religious services. According to the MOIA, its primary duties include overseeing the coordination of Islamic societies and organizations, the appointment of clergy, and the maintenance and construction of mosques.2 Yet, despite its official mission to “preserve Islamic values” and protect mosques “in a manner that fits their sacred status,”3 the MOIA is complicit in a longstanding government campaign against the peninsula’s traditional heritage – Islamic or otherwise. Since 1925, the Al Saud family has overseen the destruction of tombs, mosques, and historical artifacts in Jeddah, Medina, Mecca, al-Khobar, Awamiyah, and Jabal al-Uhud. According to the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, between just 1985 and 2014 – through the MOIA’s founding in 1993 –the government demolished 98% of the religious and historical sites located in Saudi Arabia.4 The MOIA’s seemingly contradictory role in the destruction of Islamic holy places, commentators suggest, is actually the byproduct of an equally incongruous alliance between the forces of Wahhabism and commercialism.5 Compelled to acknowledge larger demographic and economic trends in Saudi Arabia – rapid population growth, increased urbanization, and declining oil revenues chief among them6 – the government has increasingly worked to satisfy both the Wahhabi religious establishment and the kingdom’s financial elite. -

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

Desert Storm"

VECTORS AND WAR - "DESERT STORM" By Joseph Conlon [email protected] The awesome technological marvels of laser-guided munitions and rocketry riveted everyone's attention during the recent Persian Gulf War. Yet, an aspect of the war that received comparatively little media attention was the constant battle waged against potential disease vectors by preventive medicine personnel from the coalition forces. The extraordinarily small number of casualties suffered in combat was no less remarkable than the low numbers of casualties due to vector-borne disease. Both statistics reflect an appreciation of thorough planning and the proper allocation of massive resources in accomplishing a mission against a well-equipped foe. A great many personnel were involved in the vector control effort from all of the uniformed services. This paper will address some of the unique vector control issues experienced before, during, and after the hostilities by the First Marine Expeditionary Force (1st MEF), a contingent of 45,000 Marines headquartered at Al Jubail, a Saudi port 140 miles south of Kuwait. Elements of the 1st MEF arrived on Saudi soil in mid-August, 1991. The 1st MEF was given the initial task of guarding the coastal road system in the Eastern Province, to prevent hostile forces from capturing the major Saudi ports and airfields located there. Combat units of the 1st Marine Division were involved in the Battle of Khafji, prior to the main campaign. In addition, 1st MEF comprised the primary force breaching the Iraqi defenses in southern Kuwait, culminating in the tank battle at the International Airport. THE VECTOR-BORNE DISEASE THREAT The vector control problems encountered during the five months preceding the war were far worse than those during the actual fighting. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

READ Middle East Brief 101 (PDF)

Judith and Sidney Swartz Director and Professor of Politics Repression and Protest in Saudi Arabia Shai Feldman Associate Director Kristina Cherniahivsky Pascal Menoret Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor of Middle East History and Associate Director for Research few months after 9/11, a Saudi prince working in Naghmeh Sohrabi A government declared during an interview: “We, who Senior Fellow studied in the West, are of course in favor of democracy. As a Abdel Monem Said Aly, PhD matter of fact, we are the only true democrats in this country. Goldman Senior Fellow Khalil Shikaki, PhD But if we give people the right to vote, who do you think they’ll elect? The Islamists. It is not that we don’t want to Myra and Robert Kraft Professor 1 of Arab Politics introduce democracy in Arabia—but would it be reasonable?” Eva Bellin Underlying this position is the assumption that Islamists Henry J. Leir Professor of the Economics of the Middle East are enemies of democracy, even if they use democratic Nader Habibi means to come to power. Perhaps unwittingly, however, the Sylvia K. Hassenfeld Professor prince was also acknowledging the Islamists’ legitimacy, of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies Kanan Makiya as well as the unpopularity of the royal family. The fear of Islamists disrupting Saudi politics has prompted very high Renée and Lester Crown Professor of Modern Middle East Studies levels of repression since the 1979 Iranian revolution and the Pascal Menoret occupation of the Mecca Grand Mosque by an armed Salafi Neubauer Junior Research Fellow group.2 In the past decades, dozens of thousands have been Richard A. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

Saudi Arabia 2019 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh

Saudi Arabia 2019 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Saudi Arabia at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to terrorism. Overall Crime and Safety Situation The U.S. Embassy in Riyadh does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The American Citizens’ Services unit (ACS) cannot recommend a particular individual or location, and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. Review OSAC’s Saudi Arabia-specific page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Crime Threats There is minimal risk from crime in Riyadh. Crime in Saudi Arabia has increased over recent years but remains at levels far below most major metropolitan areas in the United States. Criminal activity does not typically target foreigners and is mostly drug-related. For more information, review OSAC’s Report, Shaken: The Don’ts of Alcohol Abroad. Cybersecurity Issues The Saudi government continues to expand its cybersecurity activities. Major cyber-attacks in 2012 and 2016 focused on the private sector and on Saudi government agencies, spurring action from Saudi policymakers and local business leaders. The Saudi government, through the Ministry of Interior (MOI), continues to develop and expand its collaboration with the U.S. -

TIR/GE6871/SDG CIRCULAR LETTER No 02 - Geneva, 22 January 2020

TIR/GE6871/SDG CIRCULAR LETTER No 02 - Geneva, 22 January 2020 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: The Saudi Automobile and Touring Association (SATA/098), as the issuing and guaranteeing association for TIR carnets in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, will begin its TIR issuing and guaranteeing activities from 23 January 2020 Addressees: TIR Carnet issuing and guaranteeing Associations We are pleased to inform you that the “Saudi Automobile & Touring Association” (SATA/098) that has been designated by the competent authorities of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as the issuing and guaranteeing association for TIR carnets on its territory in conformity with article 6 and Annex 9, part I of the TIR Convention, will start its issuing and guaranteeing activities on 23 January 2020. Following the approval of the IRU competent body, SATA became an associate member of IRU and underwent a thorough TIR admission process, which was accomplished with success. The International Insurers have confirmed that the guarantee will be provided for both TIR carnets issued by SATA and TIR carnets issued by other TIR issuing associations affiliated to IRU and used on the territory of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Under the terms of Article 8.3 of the TIR Convention, the maximum sum per TIR carnet in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has been set at EUR 100,000. Thus, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will be considered a country in which TIR transports can be arranged as of 23 January 2020. The activation of the TIR system in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia brings the number of TIR operational countries to 63. -

Saudi Arabia

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS BRANCH/SOILS UNIT IL REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST ASIA IRAQ A RAPID ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACTS OF THE IRAQ-KUWAIT CONFLICT ON TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS PART HI SAUDI ARABIA SEPTEMBER1991 ( LU Ci UNiTED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME 0 , w TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS BRANCH)SOILS UNiT REGIONAL OFFiCE FOR WEST ASIA A. RAPID ASSESSMENT \C 410FP Oi ANO OF THE IMPACTS OF THE IE.AQ-IcrJWAIT CONFLICT ON TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS PART THREE i A Report prepared for the United Nations Environment Programme by CAAFAR KARRAR KAMAL H. BATANOUNY MUHAMMAD A. MIAN Revised and Edited by p September 1991 Page Executive Summary vi-xi tntroducticn 2 Chapter I The Assianment and Execution ... 5 1.1 Background ... 5 1.2 The work assignment of the mission ... 6 1.3 Execution of the assignment ... 6 Chapter II The State of the Eiironment Before the the IracLKuwait Conflict ... 8 2.1 General ... 8 2.2 Physical Factors ... 8 2.2.1 Location . S 2.2.2 Topography and physiographic Regions ... B 2.2.3 Climate ... ii. 2.2.4 Soils ... 17 2.3 Biota ... 18 2.3.1 Fauna ... 18 2.3.2 Flora ... 20 2.3.3 Vegetation ... 21 2.4 Socto-Economic Indicators ... 22 2.5 Land Use ... 23 2.6 Institutional Set-up ... 23 2.6.1 Policy Relating to the Environment ... 23 2.6.2 Implementing Institution ... 24 Chapter III Imoact Identification and Evaluation. ... 25 3.1 War Activities ... 22 3.2 Environmental Components and kinds of Impacts ... 29 3.3 Qualitative judgement on nature, level and duration of impact results .. -

Security Council Distr

UNITED NATIONS S Security Council Distr. GENERAL S/AC.26/2002/7 13 March 2002 Original: ENGLISH UNITED NATIONS COMPENSATION COMMISSION GOVERNING COUNCIL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS MADE BY THE PANEL OF COMMISSIONERS CONCERNING THE THIRD INSTALMENT OF “F2” CLAIMS S/AC.26/2002/7 Page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction .........................................................................................................1 - 2 7 I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY ..............................................................................3 - 12 11 II. COMMON CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................13 - 38 12 A. Military operations, military costs and the threat of military action..........17 - 20 13 B. Payment or relief to others ....................................................................... 21 14 C. Salary and labour-related benefits..........................................................22 - 28 14 D. Verification and valuation........................................................................ 29 15 E. Other issues..........................................................................................30 - 38 15 III. THE CLAIMS ............................................................................................. 39 - 669 17 A. Saudi Ports Authority ...........................................................................39 - 93 17 1. Business transaction or course of dealing (SAR 270,397,424) .........41 - 49 17 2. Real property (SAR 9,753,500) .....................................................50