The Effects of Fare-Collection Strategies on Transit Level of Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

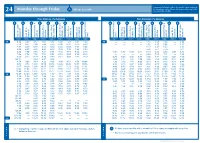

Monday Through Friday Mt

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

Reduced Cost Metro Transportation for People with Disabilities

REDUCED COST AND FREE METRO TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES Individual Day Supports are tailored services and supports that are provided to a person or a small group of no more than two (2) people, in the community. This service lends very well to the use of public transportation and associated travel training, allowing for active learning while exploring the community and its resources. While the set rate includes funding for transportation, it is important to be resourceful when possible, using available discount programs to make your funds go further. METRO TRANSIT ACCESSIBILITY CENTER The Metro Transit Accessibility Center (202)962-2700 located at Metro headquarters, 600 Fifth Street NW, Washington, DC 20001, offers the following services to people with disabilities: Information and application materials for the Reduced Fare (half fare) program for Metrobus and Metrorail Information and application materials for the MetroAccess paratransit service Consultations and functional assessments to determine eligibility for MetroAccess paratransit service Replacement ID cards for MetroAccess customers Support (by phone) for resetting your MetroAccess EZ-Pay or InstantAccess password The Transit Accessibility Center office hours are 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays, with the exception of Tuesdays with hours from 8 a.m. - 2:30 p.m. REDUCED FAIR PROGRAM Metro offers reduced fare for people with disabilities who require accessibility features to use public transportation and who have a valid Metro Disability ID. The Metro Disability ID card offers a discount of half the peak fare on Metrorail, and a reduced fare of for 90¢ cash, or 80¢ paying with a SmarTrip® card on regular Metrobus routes, and a discounted fare on other participating bus service providers. -

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart Card Or Magnetic- Your Choice

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart card or Magnetic- Your choice PATCO’s new fare collection system will feature the FREEDOM card, which will revolutionize how customers purchase their fares and travel on the PATCO system. The FREEDOM card is a smart card that will provide a high level of convenience and reliability to customers who use PATCO consistently. For customers who do not opt to use the FREEDOM card or who use PATCO infrequently, new magnetic tickets will be available. In PATCO’s current fare system, plastic tickets that use first generation magnetic technology are used. Although that technology was state of the art several decades ago, the technology is outdated and the tickets are prone to damage by devices commonly found in today’s environment. Unlike the current tickets, which are re-encoded numerous times for use after being captured by the fare gates, the new magnetic tickets will be paper tickets and will not be reused after capture. The new magnetic tickets can be purchased using either cash or coins. This means that customers choosing to purchase a ticket will not have to first stop at a change machine to convert their bills to coins. Both one- and two-ride tickets can be purchased from all new ticket vending machines located outside the fare gates. A customer wishing to purchase a magnetic ticket will simply select the prompt on the ticket vending machine screen for purchase of a ticket and then select the destination and whether a single ride or double ride ticket is desired. The ticket vending machine will list the price of the purchase. -

Effect of Fares on Transit Riding

Effect of Fares on Transit Riding JOHN F. CURTIN, Partner, Simpson & Curtin, Philadelphia • FARES are perhaps the most sensitive aspect of transit service-balancing uneasily between political pressures and the need for operating revenue. Political campaigns in major American cities have been won and lost over transit fare issues, and there is substantial evidence that patrons react to fare increases at the turnstiles as well as at the polls. The correlation of price increase with loss of transit riding has been well established. Most utility commissions use a variation of the "shrinkage formula" devised by our firm more than 20 years ago when pressures of inflation first became manifest in fare increase proposals by transit companies. But the corollary questions of price differential among competing transit services, and the effect of joint fares in coordinated transit operations, have not been so well explored. What is the "sub-modal split" of riding between surface and rapid transit connecting two points, when the fare is 15 cents on one and 25 cents on the other? How much added traffic is attracted to rapid transit when the feeder bus fare is dropped from 20cents to 10 cents? When feeder and trunk lines are separate operations, how should the feeder line discount in the combination fare be shared between them? These are fundamental questions of revenue and cost apportionment in developing coordination between surface and rapid transit systems. Auto travel switches freely between systems-from county roads to city streets to state highways-without motor ists' awareness; division of motor fuel revenues among these systems is accomplished by legislative standards with varying degrees of sophistication. -

Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: a Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data

Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: A Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data by Hazem Marwan Zureiqat B.A. in Economics Macalester College, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2008 © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of Author ………………………………………………………………………… Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 16, 2008 Certified by ……………………………………………………………………...................... Nigel H. M. Wilson Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Director, Master of Science in Transportation Program Thesis Supervisor Accepted by …………………………………………………………………………………. Daniele Veneziano Chairman, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students 2 Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: A Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data by Hazem Marwan Zureiqat Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 16, 2008, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract In many large metropolitan areas, public transport is very heavily used, and ridership is approaching system capacity in the peak periods. This has caused a shift in attention by agency decision‐makers to strategies that can more effectively manage the demand for public transport, rather than simply increase overall demand. In other words, a need has arisen to understand not only why people use public transport as opposed to other modes but also how they use public transport, in terms of their ticket, mode, and time‐of‐day choices. To that end, fares become an increasingly important policy tool that can trigger certain behavioral changes among riders. -

Passenger and Vehicle Fare Information Surcharges Seattle/Bainbridge, Seattle/Bremerton, Edmonds/Kingston Fauntleroy/Vashon

19-08-0392 Printed in the USA on recycled/recyclable paper. recycled/recyclable on USA the in Printed Seattle/Bainbridge, Seattle/Bremerton, Fauntleroy/Vashon, Point Defiance/Tahlequah, Americans with Disabilities Edmonds/Kingston Southworth/Vashon Mukilteo/Clinton Act (ADA) and Title VI Notice Seattle, Washington 98121-3014 Washington Seattle, 2901 Third Avenue Suite 500 Suite Avenue Third 2901 Passenger Regular Fare 8.65 Passenger Regular Fare 5.65 Passenger Regular Fare 5.20 It is the Washington State Department of Washington State Ferries State Washington In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 4.30 In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 2.80 In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 2.60 Transportation’s policy to ensure that no Youth Fare 4.30 Youth Fare 2.80 Youth Fare 2.60 person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin, or sex, as provided by Title VI Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 69.70 Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 45.70 Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 42.10 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or based on Monthly Ferry Pass 111.55 Monthly Ferry Pass 73.15 Monthly Ferry Pass 67.40 disability as provided by the Americans with Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Disabilities Act, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 12.35 Peak Season 16.00 Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 15.75 Peak Season 20.40 Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 7.40 Peak Season 9.70 discriminated against under any of its federally @WSFerries funded programs and activities. -

Full Free Fare Public Transport: Objectives and Alternatives September | 2020

POLICY BRIEF FULL FREE FARE PUBLIC TRANSPORT: OBJECTIVES AND ALTERNATIVES SEPTEMBER | 2020 INTRODUCTION At a time when cities must prepare for and face serious services and infrastructure must remain the overarching environmental and societal challenges, sustainable principle throughout these discussions. It is therefore urban mobility has never been this high up on the crucial to carefully consider the stated objectives which agenda. With the transversal role that public transport this measure is meant to achieve as well as its impacts, in plays in terms of urban quality of life, increasing and order to decide whether or not it is the most appropriate facilitating its access is a major challenge. Following use of public funds. In doing so, one must keep in mind this line of thought, the concept of free fare public that free public transport as such does not exist, as transport (FFPT) has been gaining traction in the public transport service and infrastructure has to be funded discourse, as several large cities have been considering one way or another. Hence the reference to free fare this possibility. public transport means that public transport users do not contribute to funding the service directly through While free public transport is often brought up in the payment of a fare. political discussions, its implementation has very concrete implications on the organisation of public Drawing from the experience of FFPT cities, this Policy transport. Yet, the strengthening of public transport Brief provides an analysis of the various stated objectives and the extent to which FFPT is the right tool to achieve them. -

The Effect of Fare Reductions on Public Transit Ridership

iL THE EFFECT OF FARE REDUCTIONS ON PUBLIC TRANSIT RIDERSHIP John R. Caruolo Roger P. Roess May 1974 PROJECT" REPORT This document was produced as part of a program of Research and Training in Urban Transportation sponsored by UMTA, USDOT. The results and views expressed are the independent products of university research and not necessarily concurred in by UMTA. Prepared for DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION URBAN MASS TRANSPORTATION ADMINISTRATION RESEARCH AND EDUCATION DIVISION WASHINGTON, D. C. 20 590 1 Of Transportation we Dept. If 3*/ / 0*6 1 MIR a 1976 , I — Library Report No. UMTA-74-6-1 THE EFFECT OF FARE REDUCTIONS ON PUBLIC TRANSIT RIDERSHIP, John R. Caruolo Roger P. Roess - . May 1974 PROJECT REPORT This document was produced as part of a program of Research and Training in Urban Transportation sponsored by UMTA, USDOT. The results and views expressed are the independent products of university research and not necessarily concurred in by UMTA. Prepared for DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION URBAN MASS TRANSPORTATION ADMINISTRATION RESEARCH AND EDUCATION DIVISION WASHINGTON, D. C. 20 590 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. T*cknicol Report Documentation Page 1. Report Ho. 2. Covtmoml Accrttion No. 3. Rrcipitnt * Cotoloq No. I UMTA-74-6- 1 4. Till* Subtitle 5. Report Do»o The Effect of Fare Reductions on Public May 1974 Transit Ridership 4. Performing Orgont ration Code 8. Performing Organization Report Mo j . Caruol'o, and Roger P. -

Loudoun County Transit Commuterbus Fare Analysis

LOUDOUN COUNTY TRANSIT COMMUTERBUS FARE ANALYSIS Completed for: Loudoun County Department of Transportation and Capital Infrastructure Transit and Commuter Services Division Completed by: April 3, 2014 ATTACHMENT 1 A-1 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 3 2.0 LC Transit Ridership and Revenue Trends ......................................................... 4 2.1 Service Level Baseline ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Ridership and Ridership Trends by Service Type ......................................................... 4 2.3 System Farebox Revenue ............................................................................................ 7 3.0 Characteristics that Influence Ridership ............................................................ 9 3.1 Consideration of Various Characteristics ....................................................................... 9 3.2 Influencing Characteristics ............................................................................................16 4.0 Fare Policy Framework and Proposed Fare Scenario ..................................... 20 4.1 National Perspectives ..................................................................................................20 4.2 Peer Review ................................................................................................................21 4.3 Fare Policy and Recommended -

BART Basics Guide

Create your custom end-to-end trip BART at www.bart.gov/planner using our multi-modal Trip Planner. Basics Download the official BART app for trip planning, real-time departures, service Guide advisories, and more. For personalized help with trip planning, JUNE 2020 call (510) 465-BART (2278), Monday Free through Friday from 8 am to 6 pm to speak with a Representative. Other important phone numbers: BART Main Number TDD Service (510) 464-6000 (510) 839-2220 BART Police Lost and Found (510) 464-7000 (510) 464-7090 Elevator Availability Bike Locker Info (510) 834-5438 or (510) 464-7133 (888) 235-3828 Ticket Exchange/ Clipper Customer Service Refund Information www.clippercard.com (510) 464-6841 (877) 878-8883 TDD/TTY: 711 or Parking Programs (800) 735-2929 www.bart.gov/parking Train schedules published in BART brochures do not anticipate service disruptions and are approximations for a normal trip. BART cannot assume responsibility for inconvenience, expense or damage resulting from errors in time estimates, delayed trains, fares, failure to make connections or shortage of equipment. Time schedules and equipment shown in this document are subject to change without notice. Printed on recycled paper. Please share or recycle this brochure. Bay Area Rapid Transit District P.O. Box 12688 Oakland, CA 94604-2688 © BART 2020 06/20 25M Welcome to BART Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) provides fast, reliable transportation connecting the San Francisco Peninsula with Oakland, Berkeley, Fremont, Walnut Creek, Dublin/Pleasanton, and other cities in the East Bay and now, Santa Clara County. 1 BART has been a proud part of the Bay Area for more than 45 years. -

The Effects of the Selective Enlargement of Fare-Free Public

sustainability Article The Effects of the Selective Enlargement of Fare-Free Public Transport Krzysztof Grzelec and Aleksander Jagiełło * Faculty of Economics, University of Gdansk, Armii Krajowej 119/121, 81-824 Sopot, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-58-523-1366 Received: 3 July 2020; Accepted: 6 August 2020; Published: 7 August 2020 Abstract: In recent years fare-free public transport (FFPT) found itself at the centre of attention of various groups, such as economists, transport engineers and local authorities, as well as those responsible for the organisation of urban transport. The FFPT is hoped to be the answer to contemporary transport-related problems within cities, problems which largely result from insensible proportions between trips carried out via personal mode of transportation and those completed by the means of public transport. This article reviews the motives and effects connected with the introduction to date of fare-free transport zones across the globe. It also presents, using data obtained in market research, the actual impact of a selective extension of the entitlement to free fares on the demand for urban transport services. The effects observed in other urban transport systems were then compared against those observed in relation to one, examined system. Analyses of observed FFPT implementation effects were then used to establish good and bad practices in the introduction of FFPT. The article also contains forecasts on the effect of the extension of entitlement to free fares and an increase in the public transport offer may have on the volume of demand for such services. -

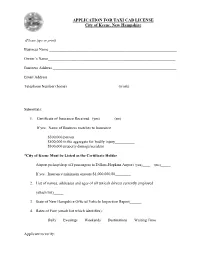

Application for Vehicle for Hire

APPLICATION FOR TAXI CAB LICENSE City of Keene, New Hampshire (Please type or print) Business Name _________________________________________________________________ Owner’s Name_________________________________________________________________ Business Address _______________________________________________________________ Email Address__________________________________________________________________ Telephone Number (home) ______________________ (work) _______________________ Submittals: 1. Certificate of Insurance Received (yes) ____ (no) _____ If yes: Name of Business matches to Insurance_______ $300,000/person __________ $500,000 in the aggregate for bodily injury__________ $300,000 property damage/accident____________ *City of Keene Must be Listed as the Certificate Holder Airport pickup/drop off passengers to Dillant-Hopkins Airport (yes)____ (no)_____ If yes: Insurance minimum amount $1,000,000.00________ 2. List of names, addresses and ages of all taxicab drivers currently employed (attach list)_____ 3. State of New Hampshire Official Vehicle Inspection Report______ 4. Rates of Fare (attach list which identifies): Daily___ Evenings___ Weekends___ Destinations___ Waiting Time_____ Applicant to verify: 1. Signage to include the phrase “Taxi” if not contained within the Company Name with Phone #: Magnetic _____ Lettering _____ Paint_______ 2. Rates of fares on a printed card and in plain view___________ 3. Card containing driver’s name with ID on a 3 X 5 “__________ _____________________________________ ____________________________