Full Free Fare Public Transport: Objectives and Alternatives September | 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

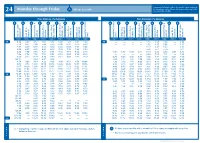

Monday Through Friday Mt

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

The Demand for Public Transport: a Practical Guide

The demand for public transport: a practical guide R Balcombe, TRL Limited (Editor) R Mackett, Centre for Transport Studies, University College London N Paulley, TRL Limited J Preston, Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford J Shires, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds H Titheridge, Centre for Transport Studies, University College London M Wardman, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds P White, Transport Studies Group, University of Westminster TRL Report TRL593 First Published 2004 ISSN 0968-4107 Copyright TRL Limited 2004. This report has been produced by the contributory authors and published by TRL Limited as part of a project funded by EPSRC (Grants No GR/R18550/01, GR/R18567/01 and GR/R18574/01) and also supported by a number of other institutions as listed on the acknowledgements page. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting and funding organisations TRL is committed to optimising energy efficiency, reducing waste and promoting recycling and re-use. In support of these environmental goals, this report has been printed on recycled paper, comprising 100% post-consumer waste, manufactured using a TCF (totally chlorine free) process. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The assistance of the following organisations is gratefully acknowledged: Arriva International Association of Public Transport (UITP) Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC) Local Government Association (LGA) Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) National Express Group plc Department for Transport (DfT) Nexus Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Network Rail Council (EPSRC) Rees Jeffery Road Fund FirstGroup plc Stagecoach Group plc Go-Ahead Group plc Strategic Rail Authority (SRA) Greater Manchester Public Transport Transport for London (TfL) Executive (GMPTE) Travel West Midlands The Working Group coordinating the project consisted of the authors and Jonathan Pugh and Matthew Chivers of ATOC and David Harley, David Walmsley and Mark James of CPT. -

Sustainable Urban Mobility and Public Transport in Unece Capitals

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS This publication is part of the Transport Trends and Economics Series (WP.5) New York and Geneva, 2015 ©2015 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. Email: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations’ publication issued by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Maps and country reports are only for information purposes. Acknowledgements The study was prepared by Mr. Konstantinos Alexopoulos and Mr. Lukasz Wyrowski. The authors worked under the guidance of and benefited from significant contributions by Dr. Eva Molnar, Director of UNECE Sustainable Transport Division and Mr. Miodrag Pesut, Chief of Transport Facilitation and Economics Section. ECE/TRANS/245 Transport in UNECE The UNECE Sustainable Transport Division is the secretariat of the Inland Transport Committee (ITC) and the ECOSOC Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals. -

Rail-Based Public Transport Service Quality and User Satisfaction

Ibrahim ANH, Borhan MN, Md. Yusoff NI, Ismail A. Rail-based Public Transport Service Quality and User Satisfaction... AHMAD NAZRUL HAKIMI IBRAHIM, M.Sc.1 Human-Transport Interaction E-mail: [email protected] Review MUHAMAD NAZRI BORHAN, Ph.D.1 Submitted: 23 May 2019 (Corresponding author) Accepted: 19 Feb. 2020 E-mail: [email protected] NUR IZZI MD. YUSOFF, Ph.D.1 E-mail: [email protected] AMIRUDDIN ISMAIL, Ph.D.1 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Department of Civil Engineering Faculty of Engineering and Built Environment Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia RAIL-BASED PUBLIC TRANSPORT SERVICE QUALITY AND USER SATISFACTION – A LITERATURE REVIEW ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION While rail-based public transport is clearly a more In today’s society, public transport plays a vi- advanced and preferable alternative to driving and a way tal role both in urban and rural settings and most of overcoming traffic congestion and pollution problems, people are either directly or indirectly affected by the rate of uptake for rail travel has remained stagnant as a result of various well-known issues such as that com- the quality, availability and accessibility of public muters either use a more reliable and comfortable alter- transport services. Many countries have prioritised native to get from A to B and/or that they are not satisfied developing good public rail services in order to cut with the quality of service provided. This study examined down on car dependency. Indeed, it is now univer- the factor of user satisfaction regarding rail-based public sally recognised that dependence on cars is a very transport with the aim of discovering precisely what fac- negative development which has only led to traffic tors have a significant effect on the user satisfaction and jams, environmental problems, noise, accidents and uptake of rail travel. -

The Effects of Fare-Collection Strategies on Transit Level of Service

Transportation Research Record 1036 79 The Effects of Fare-Collection Strategies on Transit Level of Service UPALI VANDEBONA and ANTHONY J. RICHARDSON ABSTRACT It is known that different fare-collection strategies have different passenger boarding and alighting rates for street-based public transport services. In this pape r, various models of stop service times are reviewed, the available empirical observations of boarding and alighting rates are summarized, and the effects of different average boarding rates and coefficients of variation of boarding rates on the route performance of a tram (light rail transit) service are examined. The analysis is conducted using the TRAMS (Transit Route Anima tion and Modeling by Simulation) package. This modeling package is briefly described with particular attention to the passenger demand subroutine as well as the tram stop service times subroutine. As a result o f the analysis , it was found that slower boarding rates produce a slower and less reliable service along the route. The variability of boarding rates has no effect on route travel time but does contribute to greater unreliability in level of service. It is concluded that these level-of-service effects need to be considered when assessing the effect of changes in fare-collection strategies. Public transport operators and managers have found systems to proof-of-payment systems will generally themselves under increasing pressure in recent years bring about significant level-of-service improve because of conflicting expectations from different ments that should be considered in any analysis of groups in the community. On the one hand, public such fare collection strategies. -

Reduced Cost Metro Transportation for People with Disabilities

REDUCED COST AND FREE METRO TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES Individual Day Supports are tailored services and supports that are provided to a person or a small group of no more than two (2) people, in the community. This service lends very well to the use of public transportation and associated travel training, allowing for active learning while exploring the community and its resources. While the set rate includes funding for transportation, it is important to be resourceful when possible, using available discount programs to make your funds go further. METRO TRANSIT ACCESSIBILITY CENTER The Metro Transit Accessibility Center (202)962-2700 located at Metro headquarters, 600 Fifth Street NW, Washington, DC 20001, offers the following services to people with disabilities: Information and application materials for the Reduced Fare (half fare) program for Metrobus and Metrorail Information and application materials for the MetroAccess paratransit service Consultations and functional assessments to determine eligibility for MetroAccess paratransit service Replacement ID cards for MetroAccess customers Support (by phone) for resetting your MetroAccess EZ-Pay or InstantAccess password The Transit Accessibility Center office hours are 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays, with the exception of Tuesdays with hours from 8 a.m. - 2:30 p.m. REDUCED FAIR PROGRAM Metro offers reduced fare for people with disabilities who require accessibility features to use public transportation and who have a valid Metro Disability ID. The Metro Disability ID card offers a discount of half the peak fare on Metrorail, and a reduced fare of for 90¢ cash, or 80¢ paying with a SmarTrip® card on regular Metrobus routes, and a discounted fare on other participating bus service providers. -

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart Card Or Magnetic- Your Choice

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart card or Magnetic- Your choice PATCO’s new fare collection system will feature the FREEDOM card, which will revolutionize how customers purchase their fares and travel on the PATCO system. The FREEDOM card is a smart card that will provide a high level of convenience and reliability to customers who use PATCO consistently. For customers who do not opt to use the FREEDOM card or who use PATCO infrequently, new magnetic tickets will be available. In PATCO’s current fare system, plastic tickets that use first generation magnetic technology are used. Although that technology was state of the art several decades ago, the technology is outdated and the tickets are prone to damage by devices commonly found in today’s environment. Unlike the current tickets, which are re-encoded numerous times for use after being captured by the fare gates, the new magnetic tickets will be paper tickets and will not be reused after capture. The new magnetic tickets can be purchased using either cash or coins. This means that customers choosing to purchase a ticket will not have to first stop at a change machine to convert their bills to coins. Both one- and two-ride tickets can be purchased from all new ticket vending machines located outside the fare gates. A customer wishing to purchase a magnetic ticket will simply select the prompt on the ticket vending machine screen for purchase of a ticket and then select the destination and whether a single ride or double ride ticket is desired. The ticket vending machine will list the price of the purchase. -

Effect of Fares on Transit Riding

Effect of Fares on Transit Riding JOHN F. CURTIN, Partner, Simpson & Curtin, Philadelphia • FARES are perhaps the most sensitive aspect of transit service-balancing uneasily between political pressures and the need for operating revenue. Political campaigns in major American cities have been won and lost over transit fare issues, and there is substantial evidence that patrons react to fare increases at the turnstiles as well as at the polls. The correlation of price increase with loss of transit riding has been well established. Most utility commissions use a variation of the "shrinkage formula" devised by our firm more than 20 years ago when pressures of inflation first became manifest in fare increase proposals by transit companies. But the corollary questions of price differential among competing transit services, and the effect of joint fares in coordinated transit operations, have not been so well explored. What is the "sub-modal split" of riding between surface and rapid transit connecting two points, when the fare is 15 cents on one and 25 cents on the other? How much added traffic is attracted to rapid transit when the feeder bus fare is dropped from 20cents to 10 cents? When feeder and trunk lines are separate operations, how should the feeder line discount in the combination fare be shared between them? These are fundamental questions of revenue and cost apportionment in developing coordination between surface and rapid transit systems. Auto travel switches freely between systems-from county roads to city streets to state highways-without motor ists' awareness; division of motor fuel revenues among these systems is accomplished by legislative standards with varying degrees of sophistication. -

Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: a Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data

Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: A Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data by Hazem Marwan Zureiqat B.A. in Economics Macalester College, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2008 © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of Author ………………………………………………………………………… Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 16, 2008 Certified by ……………………………………………………………………...................... Nigel H. M. Wilson Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Director, Master of Science in Transportation Program Thesis Supervisor Accepted by …………………………………………………………………………………. Daniele Veneziano Chairman, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students 2 Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: A Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data by Hazem Marwan Zureiqat Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 16, 2008, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract In many large metropolitan areas, public transport is very heavily used, and ridership is approaching system capacity in the peak periods. This has caused a shift in attention by agency decision‐makers to strategies that can more effectively manage the demand for public transport, rather than simply increase overall demand. In other words, a need has arisen to understand not only why people use public transport as opposed to other modes but also how they use public transport, in terms of their ticket, mode, and time‐of‐day choices. To that end, fares become an increasingly important policy tool that can trigger certain behavioral changes among riders. -

Passenger and Vehicle Fare Information Surcharges Seattle/Bainbridge, Seattle/Bremerton, Edmonds/Kingston Fauntleroy/Vashon

19-08-0392 Printed in the USA on recycled/recyclable paper. recycled/recyclable on USA the in Printed Seattle/Bainbridge, Seattle/Bremerton, Fauntleroy/Vashon, Point Defiance/Tahlequah, Americans with Disabilities Edmonds/Kingston Southworth/Vashon Mukilteo/Clinton Act (ADA) and Title VI Notice Seattle, Washington 98121-3014 Washington Seattle, 2901 Third Avenue Suite 500 Suite Avenue Third 2901 Passenger Regular Fare 8.65 Passenger Regular Fare 5.65 Passenger Regular Fare 5.20 It is the Washington State Department of Washington State Ferries State Washington In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 4.30 In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 2.80 In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 2.60 Transportation’s policy to ensure that no Youth Fare 4.30 Youth Fare 2.80 Youth Fare 2.60 person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin, or sex, as provided by Title VI Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 69.70 Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 45.70 Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 42.10 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or based on Monthly Ferry Pass 111.55 Monthly Ferry Pass 73.15 Monthly Ferry Pass 67.40 disability as provided by the Americans with Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Disabilities Act, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 12.35 Peak Season 16.00 Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 15.75 Peak Season 20.40 Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 7.40 Peak Season 9.70 discriminated against under any of its federally @WSFerries funded programs and activities. -

How These 7 European Cities Are Leading Smart Transit

Take Advantage of Change Best in Class: How These 7 European Cities are Leading Smart Transit WhiteBest in Class: How ThesePaper 7 European Cities are Leading Smart Transit [v.1.0] ddswireless.com1 Shutterstock / canadastock Learning From the Best “We are all about the optimization of vehicle movement; we’re the best scheduling engine in the market from the perspective of optimizing on-demand transport.” - Mark Williams, VP Sales and Global Marketing, DDS Wireless At DDS, we are in the business of moving people around. As a leader in the smart transit industry for the past 30 years, DDS has transferred on-the-ground knowledge and industry insights into mobility and integrated transit systems. And we’re seeing this trend worldwide. Leading European smart cities are harnessing the power of data and the sharing economy to offer successful integrated transit solutions. Here, we highlight the top European models revolutionizing the transit landscape, and outline recommendations for cities and transit providers looking to optimize their transportation systems. Taking cues from Europe, today’s transit providers can adapt to the rapid pace of change in the transportation space. Best in Class: How These 7 European Cities are Leading Smart Transit [v.1.0] 2 Shutterstock / Leonid Andronov What is Smart Transit? Smart transit is transit that makes use of data, sensors, automation and the internet to run and improve transportation offerings. Smart transit might advise you that your usual route is blocked due to traffic, or your bus is running ten minutes late. It similarly might notify city planners that a particular train line is at max capacity, or an intersection is being inefficiently signalled. -

Social Costs and Benefits of ´Free´Public Transport in Dutch

Social Costs and Benefits of ‘Free’ Public Transport in Dutch Cities Erasmus University Rotterdam School of Economics Master Thesis Urban, Port & Transport Economics Supervisor: drs. Giuliano Mingardo Sebastiaan van der Vliet Studentnumber 294612 2 Social Costs and Benefits of ‘Free’ Public Transport in Dutch Cities 3 4 Preface From the time I was very young, I was always fascinated by public transport. It is very interesting to see that a lot of people can be transported by public transport very efficiently in enormous cities like Paris and London. When I studied economics, I learned that price is very important in the market system of demand and supply. On first sight, delivering something ‘free’ may therefore sound strange for an economist and also for me. Nothing is ‘free’, only the rising of the sun. However, the capitalistic economic market system is not functioning perfectly, especially because of the existence of externalities, which are not incurred by the individual decision, but harm society as a whole. This is the reason for the existence of a government. Especially in transport economics, a lot of externalities exist. Because of this, ‘free’ public transport could be an interesting policy. ‘Free’ public transport has strong advocates and opponents. During my research, I discovered that not a lot of economic academic work was produced about this interesting subject. It was hard to make a start with it, but the results are as interesting as the concept of ‘free’ public transport is. Today, in times of the credit crunch, we are thinking and reviewing economic theories. The pure market driven laisser faire policies are on its return.