Summer Reading Challenge – Impact on Children's Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Society of Friends in Wiltshire1

The Society of Friends in Wiltshire1 OR the work of George Fox in Wiltshire see Wilts Notes <§ Queries, ii, 125-9, and The Journal of George Fox, Fed. N. Penney (Cambridge Edn.). The subsequent history of the Quakers in the county can be traced from the MS. records of the various quarterly and monthly meetings, from the Friends' Book of Meetings published annually since 1789 and the List of Members of the Quarterly Meeting of Bristol and Somerset, published annually since 1874. For the MS. records see Jnl. of Friends' Hist. Soc., iv, 24. The records are now at Friends House, Euston Road, London. From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Quakers' story is of a decline which was gradual until 1750 and thereafter very rapid. The Methodists and Moravians largely supplanted them. An interesting example of the change over from Quakerism to Methodism is to be found in Thomas R. Jones' The Departed Worthy (1857). This book tells the life story of Charles Maggs, a distinguished Melksham Methodist. When Maggs first went to Melksham just after 1800 he made the acquaintance of two Methodists named Abraham Shewring and Thomas Rutty. The family names of Shewring and Rutty both occur in Melksham Quaker records between 1700 and 1750. Even more interesting is the fact that Abraham Shewring was known as " the Quaker Methodist " and that Charles Maggs found that " the quiet manner in which the service was conducted scarcely suited his warm and earnest heart "* WILTSHIRE QUARTERLY MEETING, c. 1667-1785 By 1680 the number of Quaker meetings in Wilts had reached its maximum. -

Remote Meeting 16Th September 2020 Draft

MINUTES OF THE REMOTE MEETING OF THE STANTON ST QUINTIN PARISH COUNCIL HELD BY ZOOM ON 16th SEPTEMBER 2020 1. Present: Mr A. Andrews (Chairman); Mr E. Crossley; Capt J. Godwin; Mrs G. Horton Mrs Carey (Clerk) 2. Apologies: Nil 3. Absent: Mrs S. Parker; Mrs R. Whiting 4. Public Question Time: There were four members of the public present Rob Hill, Director of Global Capital Projects, Dyson and Debbie Greaves, Project Manager joined the meeting and spoke about the proposals for the roundabout on the A429. There would also be a second roundabout on the A429/Hullavington village. This would remove the dangerous junction that there is at present. The work had started earlier this year and will impact on the main highways in October/November. The work should be completed shortly after Christmas Debbie Greaves stated that there will be a website update next week and a newsletter sent out 5. Chairman’s announcements and declarations of interest: Nil 6. Minutes: The Minutes of the Meetings held on 8th July and 24th August 2020 were taken as read and will be signed as being a true record at the next proper meeting. 7. Matters Arising: a. Highway issues: • Litter by the garage: Continue to monitor • Damage to the Village triangle/verges in Lower village: Update from Wiltshire Council. This Highways Improvement request has been added to the list of requests to be considered by the Chippenham CATG. Clerk to pursue this with Wiltshire Highways • JunctionDraft of Seagry Road with 429: See update given above • Parish Steward visits: Clerk to obtain dates of future meetings • Speed Limits: Issue sheets had been submitted to CATG • Posts on village green – issue sheet had been submitted. -

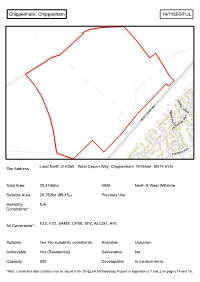

SHELAA Methodology Report in Appendices 1 and 2 on Pages 14 and 16

Chippenham: Chippenham 14/11556/FUL S O R R E L H D R A IV R E E S Y A P W WEST CEPEN WAY A T E C IN D H N LA CE Y A S W INER STA Land North of A350 West Cepen Way Chippenham Wiltshire SN14 6YG Site Address: Total Area: 20.4146ha HMA: North & West Wiltshire Suitable Area: 20.292ha (99.4%) Previous Use: Suitablity N/A Constraints*: FZ3, FZ2, SAMS, CP58, SPZ, ALCG1, HVL All Constraints*: Suitable: Yes. No suitability constraints. Available: Unknown Achievable: Yes (Residential) Deliverable: No Capacity: 620 Developable: In medium-term *Note: Constraint abbreviations can be found in the SHELAA Methodology Report in Appendices 1 and 2 on pages 14 and 16. Chippenham: Chippenham 14/11995/FUL BAYDONS LANE Land at Baydons Lane Chippenham Site Address: Total Area: 0.374ha HMA: North & West Wiltshire Suitable Area: 0.3185ha (85.2%) Previous Use: Suitablity N/A Constraints*: FZ3, FZ2, CP9, CP58, SPZ, ALCG1, CWS All Constraints*: Suitable: Yes. No suitability constraints. Available: Unknown Achievable: Yes (Residential) Deliverable: No Capacity: 14 Developable: In medium-term *Note: Constraint abbreviations can be found in the SHELAA Methodology Report in Appendices 1 and 2 on pages 14 and 16. Chippenham: Chippenham 47 BRISTOL ROAD BYTHEBROOK BARLEY LEAZE 47 MIDDLE LEAZE MIDDLEFIELD ROAD LOWER FIELD Y CORNFIELDS A W S R E P Y A M U W B N O T G N I L ALLINGTON WAY ALLINGTON L A Allington Special School Site Address: Total Area: 3.733ha HMA: North & West Wiltshire Suitable Area: 0.0386ha (1.0%) Previous Use: PDL Suitablity PP, Allocation Constraints*: PP, Allocation, SPZ, ALCG1 All Constraints*: Suitable: No. -

Final Information Farming Weekend 14 - 16 July 2017

Final Information Farming Weekend 14 - 16 July 2017 The Idea This is a fantastic weekend away together. We are going to take a select group to stay on our friends’ farm in Wiltshire. We will be doing farm work all day on the Saturday, and a bit more on the Sunday. On Sunday morning we will have our own church at the farm. Come expecting to work hard, and you will have great fun. The work is not compulsory; we just want everyone to experience “farm life”. Accommodation We shall be sleeping in tents, with showers and toilets available in the camping barn. When you arrive, the first job is to put up the tents. Bring a pillow, sleeping bag & karrimat or an air bed. Tent too, if you have one! If you don’t have a tent, please talk to us. Food Let us know of any special dietary needs. Please bring a cake to share. We will be eating outside in the garden under shelter. Travel We’ll assume people will sort their own, but happy to coordinate lift shares for people near each other, just ask if this helps you. Cost The cost is £30, for food, camping accommodation, farm expenses. This is a non-profit w/e, we simply want folk to benefit from the experience. Safety This is an important issue on a working farm. Clear advice will be given, however parents need to also assume responsibility for their children and take care! Clothing You need to bring scruffy clothes, and have some long sleeves/long trousers for working in the crops, and shifting hay bales. -

October 2019 PUBLISHED by SHERSTON PARISH COUNCIL DELIVERED FREE Pumpkins Pre-School: Aladdin’S Open Days and Opening Ceremony on His Way!

THE SHERSTON CLIFFHANGER October 2019 PUBLISHED BY SHERSTON PARISH COUNCIL DELIVERED FREE Pumpkins Pre-School: Aladdin’s Open Days and Opening Ceremony on his way! PresentedPresentedd by SHERSTONSHEHERSTR ONN DRAMADRAAMA GROUPGROUP by TobyTobyo BradfordB &Tina WebsterWebster We are delighted that our new building is now completed and that we are ready to open our doors for you to see the fi nished result! Th is invitation extends to the whole community – everyone is very welcome to pop in and have a look around and to see what will be on off er for the children in our new pre-school when it opens on SHERSTONSHERS Monday 4 November. VILLAGE HALL Open days will be running throughout the second WED 30 OCT - FRI 1 NOV 7.30 PM half of October so please pop in and join us for a SAT 2 NOV 2.30 PM & 7.30 PM By arrangement with Noda Pantomimes coff ee and a chat whilst the children take part in fun ADULTS £8 CHILD/CONS £6.50 activities in the workshops that we will be laying on Fully licensed cash bar for them. Fancy dress competition for children on Thursday Octoberob 31st during the interval. No need to book - just turn up when it’s TICKETS AVAILABLE FROM SHERSTON POST OFFICE STORES OR BOX OFFICE 07970 111601 convenient for you but if you would like to arrange an appointment you can do that too by emailing: Sherston Drama Group announces that Aladdin [email protected]. is set to fl y into Sherston on his magic carpet from Open Days Wednesday 30 October until Saturday 2 November. -

Remote Meeting 13Th May 2020

MINUTES OF THE REMOTE MEETING OF THE STANTON ST QUINTIN PARISH COUNCIL HELD BY ZOOM ON 13th MAY 2020 1. Present: Mr A. Andrews (Chairman); Mr E. Crossley; Mrs G. Horton; Mrs S. Parker; Mrs R. Whiting Cllr H. Greenman Mrs Carey (Clerk) 2. Apologies: Nil 3. Absent: Nil 4. Public Question Time: There were no members of the public present 5. Chairman’s announcements and declarations of interest: Nil 6. Minutes: The Minutes of the Meeting held on 15th January 2020 were taken as read and will be signed as being a true record at the next proper meeting. 7. Matters Arising: a. Highway issues: • Litter by the garage: Continue to monitor • Damage to the Village triangle/verges in Lower village: Update from Wiltshire Council. This Highways Improvement request has been added to the list of requests to be considered by the Chippenham CATG • Junction of Seagry Road with 429: This is tied in with the Dyson planning application and the development of the distribution centre at Junction 17 as there would be an increase in the traffic. • Parish Steward visits: Dates of future visits • Speed Limits: Issue sheets had been submitted to CATG • Posts on village green – issue sheet had been submitted. It was agreed to put in an additional issue sheet for posts on the triangle of land by the Church. • Flood on road by Bouverie Park – the Parish Steward had raised this with Wiltshire Council b. Area Board/Rural Parish Forum: On going c. OwnershipDRAFT of the Village Green; This is being processed by Wiltshire Council. -

Hullavington Airfield, Wiltshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment

Hullavington Airfield, Wiltshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Dyson Technology Ltd March 2017 90 Victoria Street, Bristol, United Kingdom, BS1 6DP Tel: +44 (0)117 925 4393 Fax: +44 (0)117 925 4239 Email: [email protected] Website: www.wyg.com WYG Environment Planning Transport Limited. Registered in England & Wales Number: 03050297 Registered Office: Arndale Court, Otley Road, Headingley, Leeds, LS6 2UJ Hullavington Airfield, Wiltshire Archaeological Desk Based Assessment Document control Document: Archaeological Desk Based Assessment Project: Hullavington Airfield, Wiltshire Client: Dyson Technology Ltd Job Number: A099314 File Origin: A099314 Hullavington Dyson DBA Revision: Draft Date: February 2017 Prepared by: Checked by: Approved By: Dr Tudor Skinner, Consultant Martin Brown, Principal Simon McCudden, Associate Archaeologist Archaeologist Director Revision: 1 Date: March 2017 Prepared by: Checked by: Approved By: Dr Tudor Skinner, Consultant Martin Brown, Principal Simon McCudden, Associate Archaeologist Archaeologist Director Description of revision: Minor text and formatting revisions. Revision: Date: Prepared by: Checked by: Approved By: Description of revision: A099314 March 2017 www.wyg.com creative minds safe hands Hullavington Airfield, Wiltshire Archaeological Desk Based Assessment Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aim and Objectives ....................................................................................................... -

Stanton St Quintin

Stanton St Quintin Parish Housing Needs Survey Survey Report June 2018 Wiltshire Council County Hall, Bythesea Road, Trowbridge BA14 8JN Contents Page Parish summary 3 Introduction 3 Aim 4 Survey distribution and methodology 4 Key findings 5 Part 1 – Households currently living in the parish 5 Part 2 – Households requiring accommodation in the parish 10 Affordability 13 Summary 14 Recommendations 14 2 1. Parish Summary The Parish of Stanton St Quintin is in the Chippenham Community Area in the north of Wiltshire. Stanton St Quintin is a small village and civil parish, with a population, according to the 2011 census, of 851. There are 240 residential properties. The St Quintin suffix is the surname of a 13-century lord of the manor. It is about 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Chippenham and 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Malmesbury. The parish includes the hamlet of Lower Stanton St Quintin, 0.6 miles (0.97 km) to the northeast on the A429. The M4 Motorway and Junction 17 built in 1971 runs near the southern edge of the parish. The village has a hall and a primary school. The primary school caters for 4 -11 years old and has approximately 100 pupils. Within Stanton St. Quintin is the Anglican Church of St Giles it is a Grade II listed building, dating from the 12 the century. In 1888 the chancel was rebuilt by C.E. Ponting and the nave windows by Christopher Whall were installed. Near to Saint Giles is Stanton Manor, listed in the Doomsday Book. The Hotel was once owned by Elizabeth 1’s Lord High Treasurer, Lord Burghley. -

2017 01 17 Council Meeting

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE STANTON ST QUINTIN PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON 17th JANUARY 2017 1. Present: Mr N. Greene (Chairman); Ms. A. Druce; Mr J. Eley; Mr P. Murton; Mr I. Plummer; Mrs R. Whiting; Cllr H. Greenman 7 members of the public 2. Apologies: Nil Letter of Resignation received from Ben King. Clerk to notify Wiltshire Council and send him a letter of thanks. 3. Public Question Time: The Chairman reiterated the procedure for the public question time. It was reported that there had been a further accident on the Seagry Road at the junction with the A429. Mr Pattison reported that he had attended the Kington St Michael Parish Council meeting re planning application 16/08756/FUL. The Chairman read out an excellent letter sent from the Clerk to Kington St Michael which expressed the views and concerns of Stanton St Quintin. Clerk to ask the officer and head of development control why Stanton St Quintin Parish Council was not consulted and to ask for the consultation period to be extended to allow for this. Cllr Greenman reported that he had called this into Committee. 4. Chairman’s announcements and declarations of interest: There were no declarations of interest. The Chairman reported that there had been an article in the local press re the grant made by Hills to the Village Hall renovation. 5. Minutes: The Minutes of the Meetings held on 15th November 2016 were taken as read and signed as being a true record: 6. Matters Arising: Action By a. Neighbourhood Plan; Cllr Greenman expressed his views on why a plan for Stanton St Quintin would shape the future of the village, particularly regarding the MoD Land and Barracks and the land adjacent to Junction 17. -

Cripps Cottage, 57 Stanton St. Quintin, Chippenham, SN14

Cripps Cottage, 57 Stanton St. Quintin, Chippenham, SN14 6DQ Semi-Detached Period Cottage 3 Good Bedrooms Character Features 2 Reception Rooms Kitchen & Utility Ample Parking 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Good Sized Gardens James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Village Setting Approximately 1,078 sq ft Price Guide: £425,000 ‘Centrally located in this Cotswold village, a characterful period cottage with light and airy accommodation extending in all to 1,078 sq.ft.’ The Property dual aspect and has a pretty fireplace, hotel/restaurant and Norman Church, Directions whilst the modern family bathroom has a whilst numerous countryside walks Cripps Cottage is a charming period shower over the bath. Benefits include surround the area. There is a regular bus From Junction 17 off the M4, follow the cottage located in the centre of the excellent ceiling height throughout, service from the village which runs from A429 north towards Malmesbury and Cotswold village of Stanton St Quintin. double glazing and central heating. Malmesbury to Chippenham. Located take the first left hand turn to Stanton St. Constructed of Cotswold stone, the just a mile away in Lower Stanton St Quintin. Enter the village and proceed cottage was sympathetically extended The property is set back from the lane by Quintin is a garage with shop selling through to locate the property on the right approximately 30 years ago whilst a large drive and front lawn with a five- everyday essentials. The neighbouring hand side just before the school. Sat nav retaining a wealth of character including bar gate leading to further parking at the larger village of Hullavington also has a postcode SN14 6DQ period fireplaces and an original bread side. -

92 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

92 bus time schedule & line map 92 Chippenham View In Website Mode The 92 bus line (Chippenham) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chippenham: 7:20 AM - 6:00 PM (2) Malmesbury: 7:55 AM - 6:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 92 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 92 bus arriving. Direction: Chippenham 92 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Chippenham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:20 AM - 6:00 PM School, Malmesbury Tuesday 7:20 AM - 6:00 PM Dark Lane, Malmesbury Wednesday 7:20 AM - 6:00 PM Cross Hayes, Malmesbury Thursday 7:20 AM - 6:00 PM 24 Cross Hayes Lane, Malmesbury Friday 7:20 AM - 6:00 PM Burton Hill, Malmesbury Burton Hill, Malmesbury Saturday 7:30 AM - 5:10 PM Police Station, Malmesbury Home Farm, Malmesbury 92 bus Info Foxley Turn, Corston Direction: Chippenham Quarry Close, St. Paul Malmesbury Without Civil Parish Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 45 min Radnor Arms, Corston Line Summary: School, Malmesbury, Dark Lane, Malmesbury, Cross Hayes, Malmesbury, Burton Hill, South End, Corston Malmesbury, Police Station, Malmesbury, Home Chippenham Road, St. Paul Malmesbury Without Civil Parish Farm, Malmesbury, Foxley Turn, Corston, Radnor Arms, Corston, South End, Corston, Telephone Telephone Exchange, Hullavington Exchange, Hullavington, Mere Avenue, Hullavington, Queens Head, Hullavington, The Star, Hullavington, Mere Avenue, Hullavington Parklands, Hullavington, St Giles Church, Stanton St Quintin, Valetta Gardens, Stanton St Quintin, Buckley Queens Head, -

Publications Leaflet

WILTSHIRE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Registered Charity No. 290284 PUBLICATIONS 2021 New & Forthcoming Publications 1 Introduction 2 Ordering by Post 2 Ordering by Post - UK and Overseas Postage Rates 2 Ordering On-line – GenFair 2 Records On-line – Findmypast 2 On-line – Free Indexes to Digital Publications 2 Publication Queries 2 Baptisms, Marriages & Burials - CMB Series 3 – 4 Parish Registers and Bishops’ Transcripts Listing 5 – 12 Other Publications on CD 13 A4 Books – County Series 14 – 18 A5 Books - Parish Series 19 Other A5 Books 20 A3 Map Of Wiltshire Parishes 1936 20 Consumer Protection - Conditions of Sale 20 New & re-released publications Alvediston Manor Court records 1633-1887 – p 18 Wiltshire Strays in Gloucester Gaol Name, date, trade, abode. 19C. – p 20 Wiltshire Emigration Association 1849-51 Names of applicants, with dates of birth & marriage, trades. – p 20 Wiltshire Fire Insurance Policy Holders 1714-1731 Name, abode, year and Guildhall Library reference. – p 20 Wiltshire Apprentices: Parish, Charity and Private Name, date of indenture, abode, trade & details of master – p 14 Broad Town Charity Apprentices Name, abode, trade & master – p 14 CD11 Wiltshire Land Tax 1780 – p 13 CD13 Wiltshire Confirmations 1703-1920 – p 13 CD14 Wiltshire Non conformist records – p 13 Forthcoming publications Salisbury St Martin baptisms & burials WFHS Publications 2021v4 1 www.wiltshirefhs.co.uk Introduction All of our current publications are in this leaflet. With few exceptions they are available in print, on CD and as downloads. Some older titles are still available on microfiche, either by post or GenFair (next page for ordering). Many individual records are also available through Findmypast (see below).