The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and Video Ezy (A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

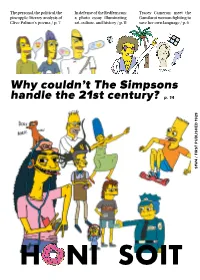

Why Couldn't the Simpsons Handle the 21St Century?

The personal, the political, the In defense of the Redfern run: Tracey Cameron: meet the pineapple: literary analysis of a photo essay illuminating Gamilaroi woman fighting to Clive Palmer’s poems / p. 7 art, culture, and history / p. 11 save her own language / p. 6 Why couldn’t The Simpsons handle the 21st century? p. 14 S1W4 / FIRST PUBLISHED 1929 PUBLISHED S1W4 / FIRST H NI SOIT LETTERS Acknowledgement of Country Fan mail We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. The University of Sydney – where we write, publish and distribute Honi Soit – is on the sovereign land of these people. As students and journalists, we recognise our complicity in the ongoing colonisation of Indigenous land. In the Senate and replace them soon regimes in Egypt and Turkey. The recognition of our privilege, we vow to not only include, but to prioritise and centre the experiences of Indigenous people, and to be reflective when we fail to. We Someone likes us with some five unidentified strangers, Someone else Brotherhood’s sectarian jihadists were recognise our duty to be a counterpoint to the racism that plagues the mainstream media, and to adequately represent the perspectives of Indigenous students at these masked corporate busybodies, in league with the al Qaeda’s sectar- our University. We also wholeheartedly thank our Indigenous reporters for the continuing contribution of their labour to our learning. Dear Sirs and Mesdames, et alia, who are not welcome in this sacred likes us ian jihadists from the beginnings of place of learning. Perhaps the words both the Libyan and Syrian conflicts, I have taken this opportunity to write of an old Master of Arts of Magdalen Congratulations to Zoe Stojanovic-Hill in 2011. -

Woolies Moves Into DVD Rental

Woolies Moves Into DVD Rental Jun 15, 2007 By Greg Peel Supermarket and just about everything else giant Woolworths (WOW) has taken another step down the online path by becoming the first major retailer in Australia to enter the popular movie rental market. If you think this seems like a left of field move for the country's prime purveyor of milk and bread, consider that the precedent has already been set by Woolies' poster girl - Tesco in the UK. Tesco commenced a similar scheme in 2004 in collaboration with Europe's biggest online DVD rental outlet Lovefilm. It now boasts 500,000 customers and 20% of the UK rental market. In the Australian version, Woolies has teamed up with local DVD rental leader Quickflix (QFX). Quickflix' subscriber base has grown by 100% in the last 12 months and now has more than 18,000 customers. It is expected that by 2010, 20% of all movie rentals will occur online. Once Australia has a fast broadband network in place, rental will occur primarily as a download. However, we're not there yet. So in the meantime, the "online" part of the Woolies business, which it will operate out of its Big W division, means that you order your DVD of choice over the internet and it will be sent out to you by snail mail. Video-Ezy take note: there will be NO FINES. You just won't be able to order your next DVD until you've returned the first one. And there is no "pay per view' cost either - one pays a monthly subscription of $9.95. -

Annual Report 2008

® Annual Report 2008 • Revised corporate mission: To provide convenient access to 2007 media entertainment • Announced decisive steps to strengthen the core rental business, enhance the company’s retail offering, and embrace digital content delivery • Positioned BLOCKBUSTER Total Access™ into a profi table and stable business • Completed Blu-ray Disc™ kiosk installation • Launched a new and improved blockbuster.com and integrated 2008 Movielink’s 10,000+ titles into the site • Improved studio relationships, with 80% of movie studios currently committed to revenue share arrangements • Enhanced approximately 600 domestic stores • Improved in-stock availability to 60% during the fi rst week a hot new release is available on DVD • Expanded entertainment related merchandise, including licensed memorabilia • Launched “Rock the Block” Concept in Reno, Dallas and New York City • Introduced consumer electronics, games and game merchandise in approximately 4,000 domestic stores • Launched new products and services nationally, including event ticketing through alliance with Live Nation • Continued to improve product assortment among confection and snack items • Launched BLOCKBUSTER® OnDemand through alliance with 2Wire® • Announced alliance with NCR Corporation to provide DVD vending 2009 • Teamed with Sonic Solutions® to provide consumers instant access to Blockbuster’s digital movie service across extensive range of home and portable devices • Began to gradually roll-out “Choose Your Terms” nationally • Announced pilot program to include online -

Global Brand List

Global Brand List Over the last ten years Superbrand, Topbrand and Grande status in over 10 countries: Marque status have become recognised as the benchmark for brand success. The organisation has produced over 5000 case DHL, American Express, Audi, AVIS, Sony, studies on brands identified as high achievers. These unique McDonald's, MasterCard, Philips, Pepsi, Nokia, stories and insights have been published in 100 branding bibles, Microsoft, Gillette, Kodak and Heinz. 77 of which were published in Europe, the Middle East and the Indian sub-continent. The following brands have achieved Superbrands ® 1C Aim Trimark Amstel Asuransi Barbie 3 Hutchison Telecom AIMC *Amsterdam AT Kearney Barca Velha 3 Korochki Air Asia Amsterdam Airport Atlas Barclaycard 36,6 Air Canada Amway Atlas Hi-Fi Barclays Bank 3FM Air France An Post Aton Barista 3M Air Liquide Anadin atv BARMER 7-Up Air Miles Anakku Audi Barnes & Noble 8 Marta Air Sahara Anchor Audrey Baron B A Blikle Airbus Ancol Jakarta Baycity Aurinkomatkat Basak¸ Emeklilik A&E Airland Andersen Consulting Australia Olympic Basak¸ Sigorta A-1 Driving Airtel Andersen Windows Committee BASF AA2000 AIS Andrex Australia Post Basildon Bond AAJ TAK Aiwa Angel Face Austrian Airlines Baskin Robins AARP Aji Ichiban Anlene Auto & General Baso Malang AB VASSILOPOULOS Ak Emekliik Ann Summers Auto Bild Bassat Ogilvy ABBA Akari Annum Automibile Association Bata abbey Akbank Ansell AV Jennings Batchelors ABC Al Ansari Exchange Ansett Avance Bates Abenson Inc Al Ghurair Retail City Antagin JRG AVE Battery ABN Amro -

List of Search Engines

A blog network is a group of blogs that are connected to each other in a network. A blog network can either be a group of loosely connected blogs, or a group of blogs that are owned by the same company. The purpose of such a network is usually to promote the other blogs in the same network and therefore increase the advertising revenue generated from online advertising on the blogs.[1] List of search engines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For knowing popular web search engines see, see Most popular Internet search engines. This is a list of search engines, including web search engines, selection-based search engines, metasearch engines, desktop search tools, and web portals and vertical market websites that have a search facility for online databases. Contents 1 By content/topic o 1.1 General o 1.2 P2P search engines o 1.3 Metasearch engines o 1.4 Geographically limited scope o 1.5 Semantic o 1.6 Accountancy o 1.7 Business o 1.8 Computers o 1.9 Enterprise o 1.10 Fashion o 1.11 Food/Recipes o 1.12 Genealogy o 1.13 Mobile/Handheld o 1.14 Job o 1.15 Legal o 1.16 Medical o 1.17 News o 1.18 People o 1.19 Real estate / property o 1.20 Television o 1.21 Video Games 2 By information type o 2.1 Forum o 2.2 Blog o 2.3 Multimedia o 2.4 Source code o 2.5 BitTorrent o 2.6 Email o 2.7 Maps o 2.8 Price o 2.9 Question and answer . -

Video Ezy Closes Door on Open Source and Chooses a More Certain Future with Windows

Video Ezy Closes Door on Open Source and Chooses a More Microsoft Customer Solution Case study Certain Future With Windows “From a business perspective Facing a multi-million dollar technology refresh across 560 Linux just didn’t stack up. It was retail outlets, Australasia’s largest video and DVD franchise going to cost the business extra operation, Video Ezy, was making decisions that would be felt far in too many ways, such as into the future. The company wanted to reduce overheads on IT administration, training and systems support and implement a cost-effective technology that integration.” would generate business confidence throughout its franchisee James Huckerby community. After a head-to-head comparison with various open CIO source technologies and deciding to go with Microsoft, Video Ezy Video Ezy hired Microsoft Consulting Services to design a Microsoft® Windows® environment for its corporate and franchise operations. The company chose what it describes as “a solid corporate approach” that provided “better value for money”. As a result, Video Ezy expects lower total cost of ownership, superior manageability and functionality, easy access to support skills and a sound technology road map for what will be a competitive and demanding future. CUSTOMER PROFILE BUSINESS SITUATION SOLUTION BENEFITS Founded in 1983, Video Ezy is Video Ezy needed to install a Following a head-to-head Lower total cost of ownership. Australasia’s largest video and new standard operating comparison with open source Superior manageability. DVD franchise operation. It has environment across its stores software, Video Ezy hired Superior functionality. more than 560 rental and retail to increase reliability, tighten Microsoft Consulting Services stores throughout Australia and security, reduce support costs to design a Windows Ready availability of skills. -

Realtime 2010 Distribution

REALTIME 2010 DISTRIBUTION Distribution is via 1000 plus well-targeted locations (art centres, galleries, universities, theatres, cinemas, bookstores, libraries cafes and music outlets). NSW 9090; Victoria 8750; Queensland 2700; South Australia 2310; WA 1950; ACT 700; Tasmania 1100; NT 100; subscribers and free list 300. NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY: Annandale Kafee Klatsch; Balmain Balmain WESTERN & OUTER SYDNEY: Bankstown Bankstown Library, Cat & Fiddle Hotel; Bondi Parade Music; Bondi Community College, Bankstown Library, Urban Theatre Beach Bondi Pavilion, City Cultural Centre; Broadway Projects; Blacktown Blacktown Community College, Humanities & Social Sciences (Transforming Cultures) Blacktown Arts Centre; Casula Casula Powerhouse UTS, The Media Store, UTS; Bronte Favoloso Espresso Arts Centre; Campbelltown Dumaresq Street Cinemas, Bar; Chatswood HUM Records; Chippendale Eora Centre, Campbelltown Art Centre; Fairfield Fairfield School of Arts, Seymour Centre, Fraser Studio, Café Giulia; Cremorne Fairfield Community Resource Centre; Gymea Hazelhurst Hayden Orpheum Picture Palace; Darlinghurst Watters Regional Gallery; Homebush Bay Australian College of Gallery,Tropicana Café, National Art School Library, DISC, Physical Education; Kingswood UWS SRC Nepean Campus, Camperdown Cellars, Stables Theatre, Edgecliff British Artsup Fine Art Supplies; Liverpool Art Matrix, Liverpool Council; Enmore Enmore Theatre; Erskineville PACT Youth Migrant Resource Centre; Milperra UWS SRC Bankstown Theatre, The Rose Hotel, Glebe Gleebooks Secondhand Campus; -

US ACTIVE BB LLC EC PAC Des Schedule 7-18-11 (2

Second Supplemental Executory Contract PAC Designation Schedule COUNTERPARTY NAME CONTRACT DESCRIPTION CURE AMOUNT Broadsign Canada INC/Broadsign USA LLC Hosted Software And Support Services For Canada $0.00 Broadsign Canada INC/Broadsign USA LLC Hosted Software And Support Services For Canada $0.00 Omnicom Canada, Inc (Tribal DDB) Canada Marketing Services $0.00 Omnicom Canada, Inc (Tribal DDB) Service Agreement $0.00 Advanced Access Content System Licensing AACS Content Provider Agreement $0.00 Administrator LLC Master Service Agreement Equinix $24,713.17 Contract Start Date: 11/2004 SDK Format License (Microsoft DRM Components), Microsoft Corporation License to Redistribute Player Components & WMDRM 10 $0.00 Server License Co-Marketing and Service Agreement for Blockbuster Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. Service with Samsung Products $22,000.00 Contract Start Date: 07/09/2009 Transportation Agreement (Truck Load Carrier) Crane Worldwide Logistics LLC $10,886.46 Contract Start Date: 06/12/2009 Transportation Agreement (Truck Load Carrier) HLS, Inc. $4,936.57 Contract Start Date: 09/16/2004 Transportation Agreement (Truck Load Carrier) Interstate Distributor Co., Inc $0.00 Contract Start Date: 03/15/2004 Service Agreement National Presort Inc. $38,758.04 Contract Start Date: 01/01/2009 Incentive Program Agreement and Supporting Amendments United Parcel Service Inc. $248,134.55 Contract Start Date: 04/17/2006 Compromise and Settlement Agreement, Bill of Sale and BAY 10004, LLC $0.00 Release and Termination Agreement - Store No. 10004 Compromise and Settlement Agreement, Bill of Sale and BAY 92943, LLC $0.00 Release and Termination Agreement - Store No. 92943 Compromise and Settlement Agreement, Bill of Sale and BAY 92944, LLC $0.00 Release and Termination Agreement - Store No. -

Project Blue Opportunity to Invest in Australia's Leading

Strictly Private and Confidential Project Blue Opportunity to invest in Australia‘s leading on demand platform 24 MAY 2013 Strictly Private and Confidential EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Media consumption habits and technologies are experiencing fundamental structural change. Hoyts, with its existing powerful movie consumer touch-points, will leverage these developments to create a new high growth business model in the Australian home entertainment / TV channel, in partnership with Studios Significant untapped Hoyts has the The standalone Business structure on demand revenues resource, skills and business case is in Australia assets to succeed attractive • High per capita • Leading, trusted • Extensive EST, tVOD and • Hoyts is seeking traditional media entertainment brand — sVOD content offer investment in its Stream consumption No. 1 cinema brand in (through Studio and Kiosk business of up • Pay-TV only 25-30% of Australia partnerships) will be to 49% homes; EST, tVOD and • Deep customer base of attractive to consumers • Seeking investment from sVOD all undeveloped movie lovers and active • Broad device coverage up to 3 Studios based on DVD renters (Kiosk) and clear development cash equity investment • Strong loyalty program roadmap and revenue share and ‗single CRM‘ system • Low cost customer content supply acquisition and delivery arrangements model returns value to • Dual returns to Studios consumers and Studio — incremental content partners revenues and equity • 15-20% EBITDA margins upside, while creating a at scale new sustainable channel -

THE MARKET There's No Doubt That Australians Love Their Movies and Games. with Over 152 Million Units of Dvds and Games Rente

THE MARKET Malaysia, Fiji and the There’s no doubt that United Arab Emirates. Australians love their With almost 1000 stores movies and games. With worldwide, Video Ezy is over 152 million units of highly respected within DVDs and games rented the home entertainment and $1.1 billion worth of industry. movies and games bought each year, HISTORYHISTORYHISTORY Australians invest more Video Ezy was established money per capita in in 1983, with the first store home entertainment than in Sydney. Video Ezy is any other country in the now the largest DVD world. rental and retail chain in Video Ezy’s core Australia with 518 stores market is DVD and and 3 million active Games rental, however members. over recent years, the The first Video Ezy company has been store to be set-up focusing on growth overseas was in New opportunities in the Zealand in 1998, which lucrative retail market, quickly grew to 162 stores which has grown at a 60% in New Zealand alone, rate year on year. Video making Video Ezy the Ezy has the lion’s share market leader in that of the Australian DVD country with 40% market rental market, accounting for 40% of total market Video Ezy is adapting share. Following this, Video Ezy expanded share, compared with 30% held by its nearest quickly to new technologies, into the South East Asian market in March competitor. addressing challenges in the 1999. This market was considered by many as market, including an impossible market to conquer, given the DVD mail order, Pay impact of piracy, but when Video Ezy opened TV and legal film its first store in Bangkok, it became apparent downloads direct that consumers were enthusiastic for quality from distributors and product and a brand they could trust. -

Australia-Volume-4-Video-Ezy.Pdf

business methods. Video Ezy has also simplified ordering with its own dedicated warehouse, where orders ru·e filled from one location, saving on freight and allowing customer special orders to be delivered to stores. With over 12,000 titles in stock, stores reap the rewards of this immediately. RECENT DEVELOPMEN'IS Video Ezy's new Windows-based point-of-sale Ezy does iL system, 'Ezy Retail', is the most advanced and ,.,..- powetful POS software system in the world. It has been des ig ned specifically for the home BRAND VALUES entettainment market, and to Video Ezy's speci Video Ezy is now developing significant points As a brand, Video Ezy needs little introduction to fications and offerings. It allows information to be of difference in the mru·ketplace for franchisees with the majority of Australians. Its aim has always been centrally created and pushed down the line to the the recent 'Ezy Exclusive' releases. Award winning to understand cleru·Iy what the home entertainment stores, both as real time and locally stored data. It titles such as 'Dinotopia', winner of the 2003 award customer wants, and deliver it better than anyone THE MARKET industry to provide rental provides comprehensive reporting capabilities, for best special feature DVD, and TV serials such else. The brand's populru·ity shows how successful The home entertainment market has followed many movies to the public. In its 21st inventory management and collection abilities, as 'Will and Grace' and 'King Pin' will provide that has been. paths over the past decades, most significantly from year it ts the largest giving Video Ezy one of the most comprehensive diversity of titles.