INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Borobudur 1 Pm

BOROBUDUR SHIP RECONSTRUCTION: DESIGN OUTLINE The intention is to develop a reconstruction of the type of large outrigger vessels depicted at Borobudur in a form suitable for ocean voyaging DISTANCES AND DURATION OF VOYAGES and recreating the first millennium Indonesian voyaging to Madagascar and Africa. Distances: Sunda Strait to Southern Maldives: Approx. 1600 n.m. The vessel should be capable of transporting some Maldives to Northern Madagascar: Approx. 1300 n.m. 25-30 persons, all necessary provisions, stores and a cargo of a few cubic metres volume. Assuming that the voyaging route to Madagascar was via the Maldives, a reasonably swift vessel As far as possible the reconstruction will be built could expect to make each leg of the voyage in using construction techniques from 1st millennium approximately two weeks in the southern winter Southeast Asia: edge-doweled planking, lashings months when good southeasterly winds can be to lugs on the inboard face of planks (tambuku) to expected. However, a period of calm can be secure the frames, and multiple through-beams to experienced at any time of year and provisioning strengthen the hull structure. for three-four weeks would be prudent. The Maldives would provide limited opportunity There are five bas-relief depictions of large vessels for re-provisioning. It can be assumed that rice with outriggers in the galleries of Borobudur. They sufficient for protracted voyaging would be carried are not five depictions of the same vessel. While from Java. the five vessels are obviously similar and may be seen as illustrating a distinct type of vessel there are differences in the clearly observed details. -

“Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 2 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR ROBERT ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: PRE-ADVANCE REPORT ON THE PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES Attached is some background information regarding the speech the President will make on July 2, 1976 at the National Archives. ***************************************************************** TAB A The Event and the Site TAB B Statement by President Truman dedicating the Shrine for the Delcaration, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, December 15, 1952. r' / ' ' ' • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR BOB ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: NATIONAL ARCHIVES ADDENDUM Since the pre-advance visit to the National Archives, the arrangements have been changed so that the principal speakers will make their addresses inside the building . -

Take a Lesson from Butch. (The Pros Do.)

When we were children, we would climb in our green and golden castle until the sky said stop. Our.dreams filled the summer air to overflowing, and the future was a far-off land a million promises away. Today, the dreams of our own children must be cherished as never before. ) For if we believe in them, they will come to believe in I themselves. And out of their dreams, they will finish the castle we once began - this time for keeps. Then the dreamer will become the doer. And the child, the father of the man. NIETROMONT NIATERIALS Greenville Division Box 2486 Greenville, S.C. 29602 803/269-4664 Spartanburg Division Box 1292 Spartanburg, S.C. 29301 803/ 585-4241 Charlotte Division Box 16262 Charlotte, N.C. 28216 704/ 597-8255 II II II South Caroli na is on the move. And C&S Bank is on the move too-setting the pace for South Carolina's growth, expansion, development and progress by providing the best banking services to industry, business and to the people. We 're here to fulfill the needs of ou r customers and to serve the community. We're making it happen in South Carolina. the action banlt The Citizens and Southern National Bank of South Carolina Member F.D.I.C. In the winter of 1775, Major General William Moultrie built a fort of palmetto logs on an island in Charleston Harbor. Despite heavy opposition from his fellow officers. Moultrie garrisoned the postand prepared for a possible attack. And, in June of 1776, the first major British deftl(lt of the American Revolution occurred at the fort on Sullivan's Island. -

To the Point

Summer 2009 To The PoinT Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Chesapeake Folk Festival–July 25 The July 25 Chesapeake Folk Festival at CBMM is the one place to be to experience the essence, culture and traditions of the Bay. And it’s an opportunity that comes only once a year! This celebration of the Bay’s people, traditions, work, food and music offers a unique chance to enjoy hands-on demonstrations by regional craftspeople and live musical crab prepared a number of ways, as well as barbeque chicken prepared by St. Luke Church of Bellevue, Md., 10-layer Smith Island cakes, homemade ice cream, organic granola and organic coffee. A number of documentary films about living and working on the Bay will be introduced and screened throughout the day. “Eatin’ Crabcakes, Chesapeake Style” follows crab expert Whitey Schmidt as he lays down his commandments for eating crabcakes. “Chesapeake Bugeye” features Sidney Dickson and Dr. John Hawkinson and the log bugeye vessel they performances by the Zionaires, the New Gospelites, Chester constructed. Other films include: River Runoff, and the Raging Unstoppables. There will also “Charlie Obert’s Barn,” “Band be skipjack and buyboat rides on the Miles River along with Together” (a 7-minute preview), plenty of crab cakes, beer and barbeque chicken. “Island Out of Time,” “Hands of “The festival is a way to celebrate the Bay’s traditions and Harvest” (screening), “Muskrat the people and work being done here on the Bay right now,” Lovely,” “Watermen,” and “The says Dr. Melissa McLoud, director of the Museum’s Breene M. New American Farmer.” Kerr Center for Chesapeake Studies. -

Occupational Safety

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH STANDARDS PART 7 Longshoring HAWAII ADMINISTRATIVE RULES TITLE 12 DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SUBTITLE 8 DIVISION OF OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH PART 7 OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH STANDARDS FOR LONGSHORING Chapter 12-190 Longshoring This unofficial copy varies from the administrative rules format in that all sections follow directly after the previous section; small letters designating subsections are in bold type; page numbers have been added to the bottom center of each page; headers do not include the section number, only the title and chapter number; and sections that incorporate federal (Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration) standards through reference include the federal standard. These variations facilitate changes to and use of the HIOSH rules and standards. This is an official copy in all other respects. HAWAII ADMINISTRATIVE RULES §12-190 TITLE 12 DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SUBTITLE 8 DIVISION OF OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH PART 7 SAFETY AND HEALTH REGULATIONS FOR LONGSHORING CHAPTER 190 LONGSHORING §12-190-1 Incorporation of federal standard §12-190-1 Incorporation of federal standard. Title 29, Code of Federal Regulations. Part 1918 entitled “Safety and Health Regulations for Longshoring”, published by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, on July 9, 1974; and the amendments published on July 22, 1977; August 24, 1987; February 9, 1994; July 19, 1994; December 22, 1994; February 13, 1996; July 25, 1997; December 1, 1998; August 27, 1999; November 12, 1999; June 30, 2000; and February 28, 2006, are made part of this chapter. -

The Poor Man's Ljungström

The poor man’s Ljungström rig (.. or how a simplified Ljungström rig can be a good alternative on a small boat...) ..by Arne Kverneland... ver. 20110722 Fredrik Ljungström: Once upon a time there lived an extraordinary man in Sweden, named Fredrik Ljungström (1875 – 1964). Like his father and brothers he turned out to be an inventor, even greater than the others. Among his over 200patents (some shared with others) the most lucrative were probably efficient steam turbines to drive electric generators and locomotives (1920) and even more important, the rotating heat regenerator which cut the coal consumption on the steam engines with over 30% (around 1930). Going through the list of patents, it is clear that he must have been a real multi-genius (.. for more info, just google Fredrik Ljungström...). The Ljungström rig – the original: Being also a keen sailor, in 1935 Mr. Ljungström came up with another brilliant idea; the Ljungström rig (Lj-rig). He had learned how dangerous it could be to handle sail on the foredeck of a small boat and his solution was radical: The diagram above of a Ljungström rig is copied from the book “RACING, CRUISING and DESIGN by Uffa Fox. (ISBN 0-907069-15-0 in UK, 0-87742-213-3 in USA). Great reading! This is a one-sail rig set on a freestanding wooden mast (.. in later designs the aft stay was omitted). The luff boltrope of the doubled sail went in a track in the mast and just as today’s roller genoas it was hoisted in spring and lowered at the end of the season. -

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Website Address

website address: http://canusail.org/ S SU E 4 8 AMERICAN CaNOE ASSOCIATION MARCH 2016 NATIONAL SaILING COMMITTEE 2. CALENDAR 9. RACE RESULTS 4. FOR SALE 13. ANNOUNCEMENTS 5. HOKULE: AROUND THE WORLD IN A SAIL 14. ACA NSC COMMITTEE CANOE 6. TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A SAILOR JOHN DEPA 16. SUGAR ISLAND CANOE SAILING 2016 SCHEDULE CRUISING CLASS aTLANTIC DIVISION ACA Camp, Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, NY June 26, Sunday, “Free sail” 10 am-4 pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) Lady Bug Trophy –Divisional Cruising Class Championships Saturday, July 9 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 10 11 am ADK Trophy - Cruising Class - Two sailors to a boat Saturday, July 16 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 17 11 am “Free sail” /Workshop Saturday July 23 10am-4pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Learn the techniques of cruising class sailing, using a paddle instead of a rudder. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) . Sebago series race #1 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) July 30, Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #2 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. 6 Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #3 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. -

The New York Sloop

The New York Sloop The most important of the sloop-rigged small-boat types used in the fisheries was the New York sloop, which had a style of hull and rig that influenced the design of both yachts and work-boats for over thirty years. The New York boats were developed sometime in the 1830's, when the centerboard had been accepted. The boats were built all about New York Bay, particularly on the Jersey shore. The model spread rapidly, and, by the end of the Civil War, the shoal centerboard sloop of the New York style had appeared all along the shores of western Long Island Sound, in northern New Jersey, and from thence southward into Delaware and Chesapeake waters. In the postwar growth of the southern fisheries, during the 1870's and 80's, this class of sloop was adopted all along the coasts of the South Atlantic states and in the Gulf of Mexico; finally, the boats appeared at San Francisco. The model did not become very popular, however, east of Cape Cod. The New York sloop was a distinctive boat—a wide, shoal centerboarder with a rather wide, square stern and a good deal of dead rise, the midsection being a wide, shallow V with a high bilge. The working sloops usually had a rather hard bilge; but in some it was very slack, and a strongly flaring side was used. Originally, the ends were plumb, and the stem often showed a slight tumble home at the cutwater. V-sterns and short overhanging counters were gradually introduced in the 1850's, particularly in the boats over 25 feet in length on deck. -

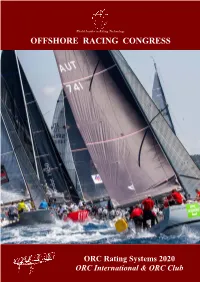

ORC Rating Systems 2020 ORC International & ORC Club 3

World Leader in Rating Technology OFFSHORE RACING CONGRESS ORC RATING SYSTEMS RATING ORC ORC Rating Systems 2020 ORC International & ORC Club 3 Copyright © 2020 Offshore Racing Congress. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is only with the permission of the Offshore Racing Congress. Cover picture: Offshore World Championship, Šibenik, Croatia 2019 Courtesy Nikos Alevromytis powered by VMG Factory Margin bars denote rule changes from 2019 version. Deleted rules from 2019 version: 208.3, 208.4, 208.6 World leader in Rating Technology ORC RATING SYSTEMS SYSTEMS RATING ORC International ORC Club 2020 Offshore Racing Congress, Ltd. www.orc.org [email protected] 1 CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................... 3 1. LIMITS AND DEFAULTS 100 General ……………………….......................... 5 101 Materials …….................................................... 6 102 Crew Weight ...................................................... 6 103 Hull ….……....................................................... 6 104 Appendages …………....................................... 7 105 Propeller ……………........................................ 7 106 Stability ……..................................................... 7 107 Righting Moment …………………………….. 8 108 Rig ……………………………………………. 9 109 Mainsail …………………………….………... 10 110 Mizzen ………………………...………...…... 10 111 Headsail ………………………..…………..… 11 112 Mizzen Staysail ……………………...………. 11 113 Symmetric Spinnaker ………………………... 12 114 Asymmetric Spinnaker ………………...……. 12 115 No Spinnaker Configuration -

The Discovery of the Sea

The Discovery of the Sea "This On© YSYY-60U-YR3N The Discovery ofthe Sea J. H. PARRY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London Copyrighted material University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Copyright 1974, 1981 by J. H. Parry All rights reserved First California Edition 1981 Published by arrangement with The Dial Press ISBN 0-520-04236-0 cloth 0-520-04237-9 paper Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 81-51174 Printed in the United States of America 123456789 Copytightad material ^gSS3S38SSSSSSSSSS8SSgS8SSSSSS8SSSSSS©SSSSSSSSSSSSS8SSg CONTENTS PREFACE ix INTROn ilCTION : ONE S F A xi PART J: PRE PARATION I A RELIABLE SHIP 3 U FIND TNG THE WAY AT SEA 24 III THE OCEANS OF THE WORI.n TN ROOKS 42 ]Jl THE TIES OF TRADE 63 V THE STREET CORNER OF EUROPE 80 VI WEST AFRICA AND THE ISI ANDS 95 VII THE WAY TO INDIA 1 17 PART JJ: ACHJF.VKMKNT VIII TECHNICAL PROBL EMS AND SOMITTONS 1 39 IX THE INDIAN OCEAN C R O S S T N C. 164 X THE ATLANTIC C R O S S T N C 1 84 XJ A NEW WORT D? 20C) XII THE PACIFIC CROSSING AND THE WORI.n ENCOMPASSED 234 EPILOC.IJE 261 BIBLIOGRAPHIC AI. NOTE 26.^ INDEX 269 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1 An Arab bagMa from Oman, from a model in the Science Museum. 9 s World map, engraved, from Ptolemy, Geographic, Rome, 1478. 61 3 World map, woodcut, by Henricus Martellus, c. 1490, from Imularium^ in the British Museum. -

The Chesapeake

A PUBLICATION OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY MARITIME MUSEUM The Chesapeake Log Winter 2012 contents Winter 2012 Aboard the Barbara Batchelder Mission Statement The mission of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime In the fall issue of The Chesapeake Log, “The Birthplace of Rosie Parks,” author Museum is to inspire an understanding Dick Cooper interviewed Irénée du Pont Jr. about his own skipjack, the Barbara of and appreciation for the rich maritime Batchelder, also built by Bronza Parks in the mid-1950s. This past September, heritage of the Chesapeake Bay and its Museum President Langley Shook, Chief Curator Pete Lesher, Project Manager tidal reaches, together with the artifacts, cultures and connections between this Marc Barto, and Shipwright Apprentice Jenn Kuhn were invited to sail on the place and its people. Chester River aboard the Barbara Batchelder with Irénée and his wife Barbara, the skipjack’s namesake. Vision Statement The vision of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is to be the premier maritime museum for studying, exhibiting, preserving and celebrating the important history and culture of the largest estuary in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay. Sign up for our e-Newsletter and stay up-to-date on all of the news and events at the Museum. Email [email protected] to be added to our mailing list. Don’t forget to visit us on Facebook! facebook.com/mymaritimemuseum Follow the Museum’s progress on historic Chesapeake boat restoration projects as well as updates for the Apprentice For a Day Program. Chesapeakeboats.blogspot.com 3 President’s Letter 13 Education 23 Calendar Check out Beautiful Swimmers, by Langley R.