Drilling Holes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8.10 Drill Grinding Device

Special Accessories 8.10 Drill Grinding Device 1. Introduction Device can accurately grind precision drill and tools, this drill grinding machine system consists of a motor and grinding wheel head composed of the drill tool in a precision six claw clip manual chuck, and with a rotatable operating handle, when swing operation handle, that produce the following actions: (A) The rotation of the drill blade in contact with the wheel. (B) Drill bit to the forward movement of the wheel, which is determined by a simple plane caused by the cam and the drive arm. (C) By the rotation of the operation 1 and 2 together, can produce about necessary, Forward and backward rotation, and rotation of the left and right around the vertical arm by means of proper adjustment of the cam drive for grinding. 2. Installation Three methods of operation (A) By the arrows in the slider on the scale required in the angle, and then tighten (12) handles. Pulled the latch position behind the locking screws, remember locking. (B) Fitted inside the grinding cam 6, the upper fixed block (2) on the green slot. (C) After setting the required bevel adjustment (1) handle rake angle 0 ° ~ 18 ° can be adjusted after the oblique angle is larger, thinner blade. The higher the M-40 Operating Manual 8-49 Special Accessories hardness of the material to be cut, then the posterior oblique angle should be smaller; lower the hardness of the material to be cut, then the posterior oblique angle should be larger. (D) If a straight shank drill bit, then caught in six claw clip directly to the head; such as slope handle, is mounted on the right sleeve of Mohs, and then to six claw tip drill chuck clamping, which can center of the drill grinding more solid and more accurate. -

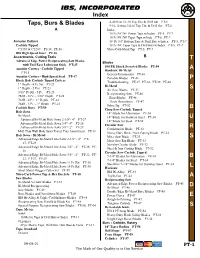

IBS, INCORPORATED T a P S B U R S B L a D E S Index

IBS, INCORPORATED Index 4-40 thru 1/2-10 Tap, Die & Drill Set PT-8 Taps, Burs & Blades 9/16-12 thru 3/4-16 Tap, Die & Drill Set PT-8 A Index 10 Pc NC/NF Power Taps w/Index PT-5, PT-7 10 Pc NC/NF Taper Taps w/Inde PT-5, PT-7 Annular Cutters 18 Pc NC Bottom Taps & Drill Bits w/Index PT-5, PT-7 Carbide Tipped 18 Pc NC Taper Taps & Drill Bits w/Index PT-5, PT-7 CT150 & CT200 PT-14, PT-16 Nitro-Carb Hand Tap PT-5, PT-7 IBS High Speed Steel PT-16 Assortments, Cutting Tools B Advanced Edge Power Reciprocating Saw Blades T Blades with Tool Ease Lubricant Stick PT-45 100 PK Shark Serrated Blades PT-54 Annular Cutters - Carbide Tipped Bandsaw, Bi-Metal A PT-15 General Information PT-36 Annular Cutters - High Speed Steel PT-17 Portable Blades PT-41 P Black Hole Carbide Tipped Cutters Troubleshooting PT-37, PT-38, PT-39, PT-40 1" Depth - 4 Pc.Set PT-23 Bi-Metal 1" Depth - 5 Pcs PT-23 Air Saw Blades PT-51 S 3/16" Depth - 5 Pc. PT-23 Reciprocating Saw PT-46 762R - 5 Pc. - 3/16" Depth PT-22 Boar Blades PT-48 763R - 4 Pc. 1" Depth PT-22 Thick Demolition PT-47 764R - 5 Pc. - 1" Depth PT-23 Sabre/Jig PT-52 Carbide Burs PT-59 Chop Saw-Carbide Tipped B Hole Saws 14" Blade for Aluminum PT-34 Bi-Metal 14" Blade for Stainless Steel PT-34 U Advanced Bi-Metal Hole Saws 2-1/8"- 4" PT-27 14" Blade for Steel PT-34 Advanced Bi-Metal Hole Saws 3/4"- 4" PT-28 Circular Saw Advanced Bi-Metal Hole Saws 5/8"- 2" PT-29 Combination Blade PT-32 R M42 Thin Wall Hole Saws Travel Tray Assortment PT-18 Heavy Duty Deck / Nail Cutting Blade PT-32 Hole Saws - Bi-Metal Miter Saw -

SM-140 (Beading Expander)

SM-140 SM-140 SPECIFICATIONS O.D. Ga. Beading Mandrel Reverse Drive Cplg. Expansion Expander No. Square Coupling Hex. Range 2” OD TUBES 10 41633-0010 2-1/2” OD TUBES 3” OD TUBES 11 41633-0011 9/16” 1.700-1.906” 2 3/4” Sq. 42360 14.3mm (43.2-48.4mm) 12 41633-0012 COMBINATION BEADING 13 41633-0013 EXPANDER 10 41634-0010 11 41634-0011 3/4” 2.200-2.440” 2-1/2 3/4” Sq. 42361 19.1mm (55.9-62.0mm) 12 41634-0012 13 41634-0013 10 41359-0010 7/8” 2.700-2.940” 3 11 41359-0011 1” Sq. 42362 22.2mm (68.6-74.7mm) 12 41359-0012 TOOL MAINTENANCE REPLACING BEADING ROLL When replacing Beading Roll, make sure it is installed with the side stamped the word ‘TOP’ or its part no. facing upward. OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS LUBRICATION ! & The tremendous force to simultaneously expand and bead the tubes, results in an ex- SERVICE MANUAL tremely heated tool. This requires a proper schedule of maintenance to lubricate the bear- ings involved to prevent their premature failure. Lubricate the support roll assembly bear- Rev: A, 2/23/2007 ings (key 8 &12) and the front guide roll assembly (key 4) frequently. Apply a good bear- ing grease through the grease fittings provided in parts (key 5, 9 &10). TO REDUCE THE RISK OF INJURY AND EQUIPMENT DAMAGE USER MUST READ AND UNDERSTAND OPERATOR’S MANUAL. Thomas C. Wilson, Inc. Thomas C. Wilson, Inc. 21-11 44th Avenue, Long Island City, New York 11101 21-11 44th Avenue, Long Island City, New York 11101 Tel: (718)729-3360 Fax: (718)361-2872 http://www.tcwilson.com Tel: (718)729-3360 Fax: (718)361-2872 http://www.tcwilson.com 8 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] SM-140 SM-140 SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS TROUBLE-SHOOTING Problem Cause & Solutions ! WARNING! Bead not complete 1. -

Tube Pullers Tube Removal Tools

TUBE PULLERS TUBE REMOVAL TOOLS Pipe Bevelling Machines Pipe Cutting Machines Grinding Machines Pipe Stands and Clamps Pipe Purging Plate Bevellers Heat Exchanger, Boiler & Bundle 3 - ” CONTINUOUS HYDRAULIC TUBE PULLER 8” 4 O.D. PULLING GUN POWERPACK FEATURES : Pulling gun communicates with electric powerpack via 9v DC control. This ensures safety and eliminates the need of electrical cord between pump and gun that other manufacturers provide. In pneumatic version communication is via pneumatic control. Available with a choice of Electric-TPP System or Pneumatic-PPP System for hazardous, explosive working environments. Microprocessor controls on powerpack and gun ensure trouble free life. Removes tube without any damage to tube sheet. Low setup time and ease of operation. High power & High speed automatic cycling, for highest speed of pull available worldwide. Auto switchover from low pressure high flow to high pressure low flow on load and again back to low pressure high flow when load is released. Automatic slow start feature to minimize risk of breaking tubes and to conserve consumables. Compact design of Powerpack and Gun. Interchangeable pulling guns with same Powerpack. 15 ton gun for light duty high speed work, 30 ton gun for heavy duty tube pulling and 45 ton gun for tubes upto 3” O.D. Pulls up to 3” OD tubes continuously, pulls up to 4” O.D. stub. Low maintenance cost and worldwide availability of components. Significant saving of time and money over conventional systems. Unit is portable with handle and mounted on four wheels for easy handling. Unit will pull tubes continuously through the gun effortlessly, needing only one man for operation. -

MODEL G0686 LARGE DRILL BIT GRINDER OWNER's MANUAL (For Models Manufactured Since 01/15)

MODEL G0686 LARGE DRILL BIT GRINDER OWNER'S MANUAL (For models manufactured since 01/15) COPYRIGHT © MAY, 2009 BY GRIZZLY INDUSTRIAL, INC., REVISED MARCH, 2019 (MN) WARNING: NO PORTION OF THIS MANUAL MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY SHAPE OR FORM WITHOUT THE WRITTEN APPROVAL OF GRIZZLY INDUSTRIAL, INC. #TS11442 PRINTED IN TAIWAN V2.03.19 This manual provides critical safety instructions on the proper setup, operation, maintenance, and service of this machine/tool. Save this document, refer to it often, and use it to instruct other operators. Failure to read, understand and follow the instructions in this manual may result in fire or serious personal injury—including amputation, electrocution, or death. The owner of this machine/tool is solely responsible for its safe use. This responsibility includes but is not limited to proper installation in a safe environment, personnel training and usage authorization, proper inspection and maintenance, manual availability and compre- hension, application of safety devices, cutting/sanding/grinding tool integrity, and the usage of personal protective equipment. The manufacturer will not be held liable for injury or property damage from negligence, improper training, machine modifications or misuse. Some dust created by power sanding, sawing, grinding, drilling, and other construction activities contains chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer, birth defects or other reproductive harm. Some examples of these chemicals are: • Lead from lead-based paints. • Crystalline silica from bricks, cement and other masonry products. • Arsenic and chromium from chemically-treated lumber. Your risk from these exposures varies, depending on how often you do this type of work. -

Disston-Catalog.Pdf

OUR HAND-MADE HISTORY From the beginning, Henry Disston knew that to compete with the then superior English tools, he would need to make the best saw the world had ever known. That was 1840. With superior manufacturing, a vision for innovation, and an earnestness of spirit, Disston created saws manufactured to usher in a new industrial age. Today, Disston is a global manufacturer of hole saws, bandsaw blades, jig saw blades, reciprocating saw blades, drill bits, and other hand and power tool related accessories for the DIY, contractor and industrial markets. Its domestic operation is a state-of-the-art production facility in South Deerfield, MA. The company also operates fabrication and production enterprises overseas. Disston’s international manufacturing and distribution capabilities combined with its history and tradition as a brand leader in the tool category for over 165 years provide its customers the optimum blend of value, performance and integrity. HOLE SAWS page Blu-Mol® Xtreme Bi-Metal Hole Saws ........................................E3 Table of Blu-Mol® Xtreme Merchandiser / Display Line ...........................E4 Blu-Mol® Xtreme Hole Saw Kits .................................................E4 Contents Blu-Mol® Bi-Metal Hole Saws ....................................................E5 Blu-Mol® Merchandiser / Display Line ........................................E6 Blu-Mol® Hole Saw Kits .............................................................E6 Blu-Mol® Sheet Metal Hole Saws ..............................................E7 -

Klik® Rivet-Nuts

MarsonMarson Rivets,Rivets, InsertsInserts && InstallationInstallation ToolsTools Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................2 General Information.......................................................................................3 Design Information.........................................................................................4 Steel Rivets.........................................................................................................5 Aluminum Rivets .............................................................................................6 Aluminum/Steel Rivets..................................................................................7 Stainless Rivets.................................................................................................8 Stainless/Steel Rivets .....................................................................................9 Closed-End Rivets .........................................................................................10 Multi-Grip Rivets............................................................................................11 Copper/Brass Rivets .....................................................................................12 Alcoa Fastening Systems (AFS) offers the broadest line of Copper/Steel Rivets......................................................................................12 blind fasteners for industrial and automotive applications in the industry. -

Metal Drill Bits Hammer Drill Stronger Than Steel Chisel Drill Bits Stone and Special Metal Drill Bits

BITS METAL DRILL BITS HAMMER DRILL STRONGER THAN STEEL CHISEL DRILL BITS STONE AND SPECIAL METAL DRILL BITS 307 | HSS-E DIN 338 cobalt 76–79 WOOD DRILL BITS 311 | HSS TIN DIN 338 steel drill bit 80–81 302 | HSS DIN 338, ground, split point 82–85 300 | HSS DIN 338, standard 86–90 300 | HSS DIN 338, standard, shank reduced 91 340 | HSS DIN 340, ground, split point, long 92 342 | HSS DIN 1869, ground, extra long 93 SAWS 344 | HSS hollow section drill bit / Facade drill bit 94 345 | HSS DIN 345 morse taper 95–96 303 | HSS DIN 1897 pilot drill bit, ground, split point, extra short 97 310 | HSS DIN 8037 carbide tipped 98 312 | HSS-G Speeder DIN 338 RN metal drill bit 99 304 | HSS Double end drill bit, ground, split point 100 315 | HSS Drill bit KEILBIT, ground 101 317 | HSS combination tool KEILBIT 102 329 | HSS countersink KEILBIT 103 327 | HSS countersink 90° DIN 335 C 104 328 | HSS deburring countersink 105 ASSORTMENTS 326 | HSS tube and sheet drill bit 106 325 | HSS step drill 107 140 | Scriber 108 320 | HSS hole saw bi-metal 109–112 SHELVES | From Pros for Pros | www.keil.eu | 73 MODULES - BITS HAMMER DRILL METAL DRILL BITS Nothing stops the metal drill bits because we offer a drill bit for every application. CHISEL HSS-E TWIST DRILL BIT 135° The HSS-E drill bit is a cobalt alloyed high performance drill bit. Even with insufficient cooling it has reserve in heat resistance. Due to the alloying addition of 5 % Co in the cutting material these drill bits can be used for working with work pieces with a tensile strength of over 800N/m². -

Tube Service Tools Tube

Tube Service Tools Power Tools Sales & Service Centers AIRETOOL TUBE SERVICE TOOLS Please note that all locations may not service all products. Please contact the nearest Apex Tool Group Sales & Service Center for the appropriate facility to handle your service requirements. DETROIT, MICHIGAN YORK, PENNSylVANIA ENGLAND INDIA Apex Tool Group Apex Tool Group Apex Tool Group Apex Power Tools India Sales & Service Center Sales & Service Center GmbH & Co. OHG Private Limited 2630 Superior Court York Service Center C/O Spline Gauges Gala No. 1, Plot No. 5 Auburn Hills, MI 48326 3990 E. Market Street Piccadilly, Tamworth, S. No. 234, 235 & 245 Tel: (248) 393 5640 York, PA 17402 Staffordshire B78 2ER Indialand Global Fax: (248) 391 6295 Tel: (717) 755 2933 United Kingdom Industrial Park Fax: (717) 757 5063 Tel: +44 1827 8741 28 Taluka-Mulsi, Phase I HOUSTON, TEXAS Fax: +44 1827 8741 28 Hinjawadi, Pune 411057 Apex Tool Group BRAZIL Maharashtra, India Sales & Service Center Apex Tool Group FRANCE 6550 West Sam Houston Sales & Service Center Apex Tool Group SNC MEXICO Parkway North, Suite 200 Av. Liberdade, 4055 25 rue Maurice Chevalier Apex Tool Group México, Houston, TX 77041 Zona Industrial - Iporanga B. P. 28 S. de R.L. de C.V. Tel: (713) 849 2364 18087-170 Sorocaba 77831 Ozoir-la-Ferrière Cedex Vialidad El Pueblito #103 Fax: (713) 849 2047 SP Brazil France Parque Industrial Querétaro Tel: +55 15 2383929 Tel: +33 1 64 43 22 00 Querétaro, QRO 76220 LEXINGTON, SC Fax: +55 15 2383260 Fax: +33 1 64 43 17 17 Mexico Apex Tool Group Tel: +52 (442) 211 3800 670 Industrial Drive CANADA GERMANY Fax: +52 (442) 103 0443 Lexington, SC 29072 Apex Tool Group Apex Tool Group Tel: (800) 845 5629 Sales & Service Center GmbH & Co. -

Hole Saw and Mandrel Assembly

Europaisches Patentamt 19 J) European Patent Office Office europeen des brevets (Tj) Publication number : 0 455 420 A2 12 EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (2?) Application number : 91303751.1 (a) Int. CI.5 : B23B 51/04 (2) Date of filing : 25.04.91 (So) Priority : 04.05.90 US 532527 (72) Inventor : Cain, William 100 Brookside Road Orange, Massachusetts 01364 (US) (43) Date of publication of application : Inventor : Emond, Ernest 06.11.91 Bulletin 91/45 28 River Road Millers Falls, Massachusetts 01349 (US) Karl @ Designated Contracting States : Inventor : Glawischnig, DE FR GB IT SE 98 Shelburne Center Road Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts 01370 (US) Inventor : Grant, Robert @ Applicant : RULE INDUSTRIES, INC. 31 Columbian Avenue 70 Blanchard Road Athol, Massachusetts 01331 (US) Burlington, MA 01803 (US) @) Representative : Woodward, John Calvin et al VENNER SHIPLEY & CO. 368 City Road London EC1V 2 OA (GB) (54) Hole saw and mandrel assembly. (57) A one piece hole saw assembly with mandrel permanently affixed to the hole saw cup. The mandrel contains a hollow shaft, a locking flange and reinforcing flange which are integ- rally formed as by machining. The locking flange of the mandrel mates with a locking hole or slot in the top surface of the hole saw cup. The reinforcing flange on the mandrel is welded during manufacture to the top surface of the hole saw cup. A pilot drill bit is inserted into the shaft core and welded to the shaft. The resulting product is a one piece hole saw assembly inten- ded for use by simple insertion of the mandrel or shaft end of the pilot drill into the chuck of a conventional electric drill. -

The MG Chemicals Professional Prototyping Process

The MG Chemicals Professional Prototyping Process Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................3 Before you begin ..........................................................................................................................................................4 Read the instructions in their entirety.......................................................................................................................4 Get everything you need...........................................................................................................................................4 Plan for safety...........................................................................................................................................................5 Plan for disposal .......................................................................................................................................................5 Design your circuit for the MG process ...................................................................................................................6 Step 1: Cutting and Routing .........................................................................................................................................6 Ingredients required..................................................................................................................................................6 Overview: -

Investigation of Nondestructive Testing Methods for Friction Stir Welding

metals Review Investigation of Nondestructive Testing Methods for Friction Stir Welding Hossein Taheri 1,* , Margaret Kilpatrick 2, Matthew Norvalls 3, Warren J. Harper 3, Lucas W. Koester 4, Timothy Bigelow 3,4 and Leonard J. Bond 3,5 1 Department of Manufacturing Engineering, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460, USA 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA; [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (W.J.H.); [email protected] (T.B.); [email protected] (L.J.B.) 4 Center for Nondestructive Evaluation (CNDE), Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Aerospace Engineering, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-912-478-7463 Received: 15 April 2019; Accepted: 23 May 2019; Published: 29 May 2019 Abstract: Friction stir welding is a method of materials processing that enables the joining of similar and dissimilar materials. The process, as originally designed by The Welding Institute (TWI), provides a unique approach to manufacturing—where materials can be joined in many designs and still retain mechanical properties that are similar to, or greater than, other forms of welding. This process is not free of defects that can alter, limit, and occasionally render the resulting weld unusable. Most common amongst these defects are kissing bonds, wormholes and cracks that are often hidden from visual inspection. To identify these defects, various nondestructive testing methods are being used. This paper presents background to the process of friction stir welding and identifies major process parameters that affect the weld properties, the origin, and types of defects that can occur, and potential nondestructive methods for ex-situ detection and in-situ identification of these potential defects, which can then allow for corrective action to be taken.