Was the Mitanni a Suzerain Or in a Coalition of States?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2014 Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait Hasan Ashkanani University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ashkanani, Hasan, "Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4980 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait by Hasan J. Ashkanani A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Thomas J. Pluckhahn, Ph.D. E. Christian Wells, Ph.D. Jonathan M. Kenoyer, Ph.D. Jeffrey Ryan, Ph.D. Date of Approval April 7, 2014 Keywords: Failaka Island, chemical analysis, pXRF, petrographic thin section, Arabian Gulf Copyright © 2014, Hasan J. Ashkanani DEDICATION I dedicate my dissertation work to the awaited savior, Imam Mohammad Ibn Al-Hasan, who appreciates knowledge and rejects all forms of ignorance. -

Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka Lands. Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka lands: Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages Gander, Max DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/klio-2014-0039 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-119374 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Gander, Max (2014). Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka lands: Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. Klio. Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte, 96(2):369-415. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/klio-2014-0039 Klio 2014; 96(2): 369–415 Max Gander Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka lands. Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages Summary: The present article contains observations on the invasion of Lycia by the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV as described in the Yalburt inscription. The author questions the commonly found identification of the land of VITIS/Wiyanwanda with the city of Oinoanda on account of the problems raised by the reading of the sign VITIS as well as of archaeological and strategical observations. With the aid of Lycian and Greek inscriptions the author argues that the original Wiya- nawanda/Oinoanda was located further south than the city commonly known as Oinoanda situated above İncealiler. These insights lead to a reassessment of the Hittite-Luwian sources concerning the conquest of Lycia. -

Extracts Relating to the Hittites from the Tel El-Amarna Letters

APPENDIX EXTRACTS RELATING TO THE HITTITES FROM THE TEL EL-AMARNA LETTERS ROM a letter of Dusratta, king of Mitanni: 1 When F all the [army] of the Hittites marched to attack my country, Tessub my lord gave it into my hands and I smote it. There was none among them who returned to his own land.' From a letter of Aziru, son of Ebed-Asherah the Amorite, to the Egyptian official Dudu : 1 0 my lord, now Khatip (Hotep) is with me. I and he will march (together). 0 my lord, the king of the land of the Hittites has marched into the land of Nukhassi (Egyp!t"an Anaugas), and the cities (there) are not strong enough to defend themselves from the king of the Hittites ; but now I and Khatip will go (to their help).' From a letter of Aziru to the Egyptian official Khai : 1 The king of the land of the Hittites is in Nukhassi, and I am afraid of him; I keep guard lest he make his way up into the land of the Amorites. And if the city of Tunip falls there will be two roads (open) to the place where he is, and I am afraid of him, and on this account I have remained (here) till his departure. But now I and Khatip will march at once.' From a letter of Aziru to the Pharaoh : 1 And now the king of the Hittites is in Nukhassi: there are two roads to Tunip, and I am afraid it will fall, and that the city [will not be strong enough] to defend itself.' Appendix From a letter of Akizzi, the governor of Qatna (in Nukhassi) on the Khabur to the Pharaoh: 1 0 my lord, the Sun-god my father made thy fathers and set his name upon them ; but now the king of the Hittites has taken the Sun-god my father, and my lord knows what they have done to the god, how it stands. -

Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Arnhem (nl) 2015 – 3 Anatolia in the bronze age. © Joost Blasweiler student Leiden University - [email protected] Hanigal9bat and the land Hana. From the annals of Hattusili I we know that in his 3rd year the Hurrian enemy attacked his kingdom. Thanks to the text of Hattusili I (“ruler of Kussara and (who) reign the city of Hattusa”) we can be certain that c. 60 years after the abandonment of the city of Kanesh, Hurrian armies extensively entered the kingdom of Hatti. Remarkable is that Hattusili mentioned that it was not a king or a kingdom who had attacked, but had used an expression “the Hurrian enemy”. Which might point that formerly attacks, raids or wars with Hurrians armies were known by Hattusili king of Kussara. And therefore the threatening expression had arisen in Hittite: “the Hurrian enemy”. Translation of Gary Beckman 2008, The Ancient Near East, editor Mark W. Chavalas, 220. The cuneiform texts of the annal are bilingual: Babylonian and Nesili (Hittite). Note: 16. Babylonian text: ‘the enemy from Ḫanikalbat entered my land’. The Babylonian text of the bilingual is more specific: “the enemy of Ḫanigal9 bat”. Therefore the scholar N.B. Jankowska1 thought that apparently the Hurrian kingdom Hanigalbat had existed probably from an earlier date before the reign of Hattusili i.e. before c. 1650 BC. Normally with the term Mittani one is pointing to the mighty Hurrian kingdom of the 15th century BC 2. Ignace J. Gelb reported 3 on “the dragomans of the Habigalbatian soldiers/workers” in an Old Babylonian tablet of Amisaduqa, who was a contemporary with Hattusili I. -

"Ancient Terqa and Its Temple of Ninkarrak: the Excavations of The

ANCIENT TERQA AND ITS TEMPLE OF NINKARRAK: THE EXCAVATIONS OF THE FIFTH AND SIXTH SEASONS Renata M. Liggett Assistant Director, Joint Expedition to Terqa Doctoral Student, Near Eastern Languages & Cultures-UCLA Introduction The historical record of an ancient region can be traced archaeologically by artifactual, archival, linguistic, artistic, architectural and ceramic records. In the developments of the past few years at, for instance, Tell Mardikh in northern Syria, a single resource, such as a grammatical element or mention of a fdreign ruler, can provide the basis or a clue for a new interpretation of the material. The excavations at Terqa are intended to incorporate all manner of data into a reconstruction of the historical record of the Mid-Euphrates region. This article provides a brief overview of the recent archaeological discoveries, which, applied to the many facets of research surrounding the ancient city of Terqa and its environs, will produce a solid understanding of a particular region at various crucial times in the history of ancient Syria. Ongoing contributions to this goal include philological research, particularly involving onomastics and applied computer technology, sphragistic (cylinder seal) analysis by an encoded com- puter data base, particularly of the Old Babylonian and Khana periods, chronological assessment of ceramic types, partly by atomic absorption sourcing techniques, and a continuing development of an advanced methodology, especially stratigraphic analysis, again applying computer technology. Associated projects also include innovations in archaeological equipment, tested on-site at Terqa, such as an instrument for overhead aerial photography. Most recently, an important orgspic geochemical study conducted on ancient samples of asphalt from Terqa /~aturq,Vol. -

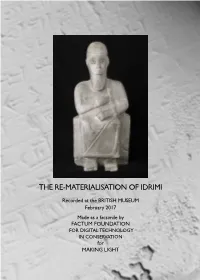

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

A Sketch of North Syrian Economic Relations in the Middle Bronze

A SKETCH OF NORTH SYRIAN ECONOMICRELATIONS IN THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE * BY JACK M. SASSON (The University of North Carolina) Northern Syria of the Middle Bronze Age, as known chiefly from the archives of Mari and Alalah VII, slowly graduatedfrom moments of relative chaos (ca. 2I00-I850) to an age of political stability (ca. I850-I625). Under the able leadership of the Yamhadian dynasty, a feudal system of relationship created one entity out of the whole region.') The evidence at our disposal allows us even to imagine a political and economic Pax Yamhadianawhich, beginning before the fall of Mari, lasted until the rise of the Hittite State and the attacks of Hattusilis I (ca. 625). *) The word 'sketch' in the title is chosen for reasons of necessity. Except for brief illuminations from the 'Cappadocian' texts and those from Egypt, heavy reliance had to be placed on the Mari and Alalah VII documents, and then only when they show evidence of foreign interconnection. The archaeology of Middle Bronze (IIa) Syria, in which the Mari age unfolds, has not been very helpful, simply because not enough North Syrian sites of that age have been excavated. The reports from the 'Amuq region (phase L), 'Atsanah (levels XVI-VIII), testify to a wide- spread use of a painted ware rounded of form, narrow necked, buff, with simple geometric designs (cross-hatching in triangles) within bands (cf. Iraq, I5 (I953), 57-65; Chronologiesin Old WorldArchaeology, p. I72). The material from Ugarit of that age being yet mostly unpublished, one looks forwardto the reports of excavation at Tilmen-Hiiyik, which is probably the site of ancient Ibla (for now, see Orientalia 33 (1964) 503-507; AJA 68 (1964), I55-56; 70 (966), I47). -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies. -

Indo-Iranian Personal Names in Mitanni: a Source for Cultural Reconstruction DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8

Onoma 54 Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences ISSN: 0078-463X; e-ISSN: 1783-1644 Journal homepage: https://onomajournal.org/ Indo-Iranian personal names in Mitanni: A source for cultural reconstruction DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8 Simone Gentile Università degli Studi di Roma Tre Dipartimento di Filosofia, Comunicazione e Spettacolo via Ostiense, 234˗236 00146 Roma (RM) Italy [email protected] To cite this article: Gentile, Simone. 2019. Indo-Iranian personal names in Mitanni: A source for cultural reconstruction. Onoma 54, 137–159. DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8 © Onoma and the author. Indo-Iranian personal names in Mitanni: A source for cultural reconstruction Abstract: As is known, some Indo˗Aryan (or Iranian) proper names and glosses are attested in documents from Egypt, Northern Mesopotamia, and Syria, related to the ancient kingdom of Mitanni (2nd millennium BC). The discovery of these Aryan archaic forms in Hittite and Hurrian sources was of particular interest for comparative philology. Indeed, some names can be readily compared to Indo˗Iranian anthroponyms and theonyms: for instance, Aššuzzana can likely be related with OPers. Aspačanā ‘delighting in horses’, probably of Median origin; Indaratti ‘having Indra as his guest’ clearly recalls Indra, a theonym which occurs both in R̥ gveda and Avesta. This paper aims at investigating the relationship between Aryan personal names preserved in Near Eastern documents and the Indo˗Iranian cultural milieu. After a thorough collection of these names, their 138 SIMONE GENTILE morphological and semantic structures are analysed in depth and the most relevant results are showed here. -

The Hittites United

The Major Assyrian Campaigns of 9C BCE (B S Curnock.) The Hittites United By P J Crowe Introducing a new historical framework for the Hittites - the fruits of two centuries of Anatolian archaeology A work in progress 121212 Successive generations of Near Eastern archaeologists have often had to admit that they could not reconcile their findings with the prevailing view of Hittite history. This paper is a summary version of an interim report for discussion of a new study initiated by B S Curnock. It demonstrates that the histories of the Empire and Neo-Hittites can be merged into a single integrated history of the Hatti Lands dating from the ninth to the mid-sixth centuries BCE. Interlocking supporting evidence is drawn from widespread and diverse sources including the ancient records of Assyria, Babylonia, Mitanni, Urartu, Syria, Egypt and the Old Testament. If this revision is followed, an alternative historical framework becomes available to the archaeologist within which many present difficulties of interpretation may find a more credible solution. Quote: "Few archaeologists have had the courage, or the time, or the overall knowledge to question the bases of the chronology they were taught and are using. For many, the chronological scale is only of peripheral interest...The tombstones of those rash souls who have questioned the fundamentals lie scattered along the dusty by-ways of history, forgotten and unlamented." John Dayton, 'Minerals, Metals, Glazing, and Man' (1978). Contact: Email: [email protected] Web site: www.thetroydeception.com (This version for private circulation; feedback invited.) 20 1 The Hittites United 121212 that the Hatti capital probably fell to Croesus in the time of Suppiluliumas II long before Ramesses III (perhaps the king Nectanebos whose wars are described by Diodorus Siculus) became king of Egypt. -

Anatolian Civilizations.Pdf

P a g e | 1 ANATOLIAN CIVILIZATIONS: “From Hittites to the Persian Domination” Text written by Erdal Yavuz Anatolia, also called Asia Minor, at the Their center was Hattusas (in Boğazköy near crossroads of Asia and Europe, has been the home Yozgat) which will also be the capital city of the of numerous peoples during the prehistoric ages, Hittite kingdoms. with well-known Neolithic settlements such as Hattians spoke a language related to the Çatalhöyük , Çayönü, Hacılar to name a few. Northwest Caucasian language group eventually The settlement of legendary Troy also starts merged with the Hittites, who spoke the Indo- in the Neolithic period and continues forward into European Hittite language. the Iron Age. In the east and south east Anatolia, one of Anatolia offered a mild climate with reliable the earliest state builders were the Hurrians, and regular rainfall necessary for a regular entering the scene toward the end of the 3rd agricultural production. Besides the timber and millennium BC stone essential for construction but deficient in Hurrians occupied large sections of eastern Mesopotamia, Anatolia had rich mines, which Anatolia and later the Cilicia region (From Alanya to provided copper, silver, iron, and gold. Mersin including the Taurus Mountains) and had a Since the peninsula is a land bridge between strong influence on the Hittite culture, language and Asia and Europe as well as the Mediterranean and mythology. the Black Sea, trade to and from the region also had However the Hurrians lost all political and been important since the prehistoric times. All the cultural identity by the last part of the 2nd above particularities made Anatolia very attractive millennium BC.