Did God Dwell in the Second Temple? Clarifying the Relationship Between Theophany and Temple Dwelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Maccabees, Chapter 1 Letter 1: 124 B.C

Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Sacred Worship Lectio Divina Bible The Second Book of Maccabees Second Maccabees can be divided as follows: I. Letters to the Jews in Egypt II. Author’s Preface III. Heliodorus’ Attempt to Profane the Temple IV. Profanation and Persecution V. Victories of Judas and Purification of the Temple VI. Renewed Persecution VII. Epilogue * * * Lectio Divina Read the following passage four times. The first reading, simple read the scripture and pause for a minute. Listen to the passage with the ear of the heart. Don’t get distracted by intellectual types of questions about the passage. Just listen to what the passage is saying to you, right now. The second reading, look for a key word or phrase that draws your attention. Notice if any phrase, sentence or word stands out and gently begin to repeat it to yourself, allowing it to touch you deeply. No elaboration. In a group setting, you can share that word/phrase or simply pass. The third reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “Where does the content of this reading touch my life today?” Notice what thoughts, feelings, and reflections arise within you. Let the words resound in your heart. What might God be asking of you through the scripture? In a group setting, you can share your reflection or simply pass. The fourth reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “I believe that God wants me to . today/this week.” Notice any prayerful response that arises within you, for example a small prayer of gratitude or praise. -

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

The Identification of “The Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon(Psssol1))

DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2011.10.29.149 The Identification of “the Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon / Unha Chai 149 The Identification of “the Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon(PssSol1)) Unha Chai* 1. The Problem The frequent references to “the righteous” and to a number of other terms and phrases2) variously used to indicate them have constantly raised the most controversial issue studied so far in the Psalms of Solomon3) (PssSol). No question has received more attention than that of the ideas and identity of the righteous in the PssSol. Different views on the identification of the righteous have been proposed until now. As early as 1874 Wellhausen proposed that the righteous in the PssSol refer to the Pharisees and the sinners to the Sadducees.4) * Hanil Uni. & Theological Seminary. 1) There is wide agreement on the following points about the PssSol: the PssSol were composed in Hebrew and very soon afterwards translated into Greek(11MSS), then at some time into Syriac(4MSS). There is no Hebrew version extant. They are generally to be dated from 70 BCE to Herodian time. There is little doubt that the PssSol were written in Jerusalem. The English translation for this study is from “the Psalms of Solomon” by R. Wright in The OT Pseudepigrapha 2 (J. Charlesworth, ed.), 639-670. The Greek version is from Septuaginta II (A. Rahlfs, ed.), 471-489; G. W. E. Nickelsburg, Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah, 203-204; K. Atkinson, “On the Herodian Origin of Militant Davidic Messianism at Qumran: New Light From Psalm of Solomon 17”, JBL 118 (1999), 440-444. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

1 the 613 Mitzvot

The 613 Mitzvot P33: The Priestly garments P62: Bringing salt with every (Commandments) P34: Kohanim bearing the offering According to the Rambam Ark on their shoulders P63: The Burnt-Offering P35: The oil of the P64: The Sin-Offering Anointment P65: The Guilt-Offering P36: Kohanim ministering in P66: The Peace-Offering 248 Positive Mitzvot watches P67: The Meal-Offering Mitzvot aseh P37: Kohanim defiling P68: Offerings of a Court that themselves for deceased has erred P1: Believing in God relatives P69: The Fixed Sin-Offering P2: Unity of God P38: Kohen Gadol should P70: The Suspensive Guilt- P3: Loving God only marry a virgin Offering P4: Fearing God P39: Daily Burnt Offerings P71: The Unconditional Guilt- P5: Worshiping God P40: Kohen Gadol's daily Offering P6: Cleaving to God Meal Offering P72: The Offering of a Higher P7: Taking an oath by God's P41: The Shabbat Additional or Lower Value Name Offering P73: Making confession P8: Walking in God's ways P42: The New Moon P74: Offering brought by a P9: Sanctifying God's Name Additional Offering zav (man with a discharge) P10: Reading the Shema P43: The Pesach Additional P75: Offering brought by a twice daily Offering zavah (woman with a P11: Studying and teaching P44: The Meal Offering of the discharge) Torah Omer P76: Offering of a woman P12: Wearing Tephillin of the P45: The Shavuot Additional after childbirth head Offering P77: Offering brought by a P13: Wearing Tephillin of the P46: Bring Two Loaves on leper hand Shavuot P78: Tithe of Cattle P14: To make Tzitzit P47: The Rosh Hashana -

The Hidden Manna

Outline of the Messages for the Full-time Training in the Spring Term of 2012 ------------------------------------------- GENERAL SUBJECT: EXPERIENCING, ENJOYING, AND EXPRESSING CHRIST Message Fifty-Five In Revelation (4) The Hidden Manna Scripture Reading: Rev. 2:17; Heb. 9:4; Exo. 16:32-34 I. The hidden manna mentioned in Revelation 2:17 was hidden in a golden pot in the Ark within the Holy of Holies—Heb. 9:4; Exo. 16:32-34: A. Placing the hidden manna in the golden pot signifies that the hidden Christ is con- cealed in the divine nature—Heb. 9:4; Col. 3:1, 3; 2 Pet. 1:4. B. The hidden manna is for those who are intimate with the Lord, those who have forsaken the world and every separation between them and God; they come into the intimacy of God’s presence, and here in this divine intimacy they enjoy the hidden manna in the divine nature—Heb. 9:4; Rev. 2:17. C. Our experience of Christ should not merely be open but also hidden in the Holy of Holies, even in Christ Himself as the Ark, the testimony of God—Heb. 10:19: 1. The golden pot is in the Ark, the Ark is in the Holy of Holies, and the Holy of Holies is joined to our spirit; if we continually touch Christ in our spirit, we will enjoy Him as the hidden manna—4:16; 1 Cor. 6:17. 2. The hidden manna is for the person who remains in the innermost part of God’s dwelling place, abiding in the presence of God in the spirit—2 Tim. -

Eng-Kjv 2MA.Pdf 2 Maccabees

2 Maccabees 1:1 1 2 Maccabees 1:10 The Second Book of the Maccabees 1 The brethren, the Jews that be at Jerusalem and in the land of Judea, wish unto the brethren, the Jews that are throughout Egypt health and peace: 2 God be gracious unto you, and remember his covenant that he made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, his faithful servants; 3 And give you all an heart to serve him, and to do his will, with a good courage and a willing mind; 4 And open your hearts in his law and commandments, and send you peace, 5 And hear your prayers, and be at one with you, and never forsake you in time of trouble. 6 And now we be here praying for you. 7 What time as Demetrius reigned, in the hundred threescore and ninth year, we the Jews wrote unto you in the extremity of trouble that came upon us in those years, from the time that Jason and his company revolted from the holy land and kingdom, 8 And burned the porch, and shed innocent blood: then we prayed unto the Lord, and were heard; we offered also sacrifices and fine flour, and lighted the lamps, and set forth the loaves. 9 And now see that ye keep the feast of tabernacles in the month Casleu. 10 In the hundred fourscore and eighth year, the people that were at Jerusalem and in Judea, and the council, and Judas, sent greeting and health unto Aristobulus, king Ptolemeus’ master, who was of the stock of the anointed priests, and to the Jews that were in Egypt: 2 Maccabees 1:11 2 2 Maccabees 1:20 11 Insomuch as God hath delivered us from great perils, we thank him highly, as having been in battle against a king. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

Manifestations of God: Theophanies in the Hebrew Prophets and the Revelation of John Kyle Ronchetto Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Classics Honors Projects Classics Department 2017 Manifestations of God: Theophanies in the Hebrew Prophets and the Revelation of John Kyle Ronchetto Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Ronchetto, Kyle, "Manifestations of God: Theophanies in the Hebrew Prophets and the Revelation of John" (2017). Classics Honors Projects. 24. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/24 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANIFESTATIONS OF GOD: THEOPHANIES IN THE HEBREW PROPHETS AND THE REVELATION OF JOHN Kyle Ronchetto Advisor: Nanette Goldman Department: Classics March 30, 2017 Table of Contents Introduction........................................................................................................................1 Chapter I – God in the Hebrew Bible..............................................................................4 Introduction to Hebrew Biblical Literature...............................................................4 Ideas and Images of God..........................................................................................4 -

Tamid 28.Pub

כ“א אייר תשע“ב Sunday, May 13, 2012 תמיד כ“ח OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) Checking on the guards (cont.) The task was delegated to the kohen who arrived first The Gemara continues its citation of the Mishnah that היו שנים שוים הממונה אומר להם הצביעו describes the procedure for making sure the guards were doing their job. T he Gemara cites the Mishnah in Yoma (22a) which tells the R’ Chiya bar Abba related R’ Yochanan’s response to story of two kohanim who were running up the ramp of the Al- this Mishnah. tar. They each wanted to be the first to reach the top and thereby merit to be the one to be able to do the service of removing the 2) Rebuke ashes from the pyre. Shockingly, one pushed the other and The Gemara cites a Beraisa in which Rebbi emphasizes caused him to break his leg. The sages realized that it was danger- the importance of rebuke. ous to have a system of allowing this privilege to be granted to Another teaching related to rebuke is recorded. anyone who would “win the race” of reaching the top of the Al- ter. They therefore changed the system to be one of drawing lots 3) Lottery among all the kohanim who arrived early. A contradiction in the Mishnah is noted about whether Tosafos HaRosh points out that it is surprising to read that a lottery was held to determine who would remove the ashes these two kohanim were running. The Yerushalmi (Berachos 1:1) from the Altar. -

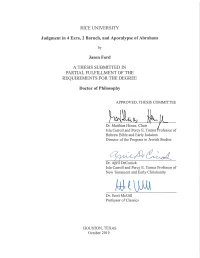

Ford-Judgment in 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and Apocalypse of Abraham FINAL

Abstract Judgment in 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and Apocalypse of Abraham By: Jason Ford When the Roman army destroyed Jerusalem’s temple in 70 CE, it altered Jewish imagination and compelled religious and community leaders to devise messages of consolation. These messages needed to address both the contemporary situation and maintain continuity with Israel’s religious history. 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and Apocalypse of Abraham are three important witnesses to these new messages hope in the face of devastation. In this dissertation I focus on how these three authors used and explored the important religious theme of judgment. Regarding 4 Ezra, I argue that by focusing our reading on judgment and its role in the text’s message we uncover 4 Ezra’s essential meaning. 4 Ezra’s main character misunderstands the implications of the destroyed Temple and, despite rounds of dialogue with and angelic interlocutor, he only comes to see God’s justice for Israel in light of the end-time judgment God shows him in two visions. Woven deeply into the fabric of his story, the author of 2 Baruch utilizes judgment for different purposes. With the community’s stability and guidance in question, 2 Baruch promises the coming of God’s judgment on the wicked nations, as well as the heavenly reward for Israel itself. In that way, judgment serves a pedagogical purpose in 2 Baruch–to stabilize and inspire the community through its teaching. Of the three texts, Apocalypse of Abraham explores the meaning of judgment must directly. It also offers the most radical portrayal of judgment. -

From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’S Iconic Texts

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2014 From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation James W. Watts, "From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts," pre- publication draft, published on SURFACE, Syracuse University Libraries, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts [Pre-print version of chapter in Ritual Innovation in the Hebrew Bible and Early Judaism (ed. Nathan MacDonald; BZAW 468; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), 21–34.] The builders of Jerusalem’s Second Temple made a remarkable ritual innovation. They left the Holy of Holies empty, if sources from the end of the Second Temple period are to be believed.1 They apparently rebuilt the other furniture of the temple, but did not remake the ark of the cove- nant that, according to tradition, had occupied the inner sanctum of Israel’s desert Tabernacle and of Solomon’s temple. The fact that the ark of the covenant went missing has excited speculation ever since. It is not my intention to pursue that further here.2 Instead, I want to consider how biblical literature dealt with this ritual innovation.