“The Challenge of Change”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hidden Manna

Outline of the Messages for the Full-time Training in the Spring Term of 2012 ------------------------------------------- GENERAL SUBJECT: EXPERIENCING, ENJOYING, AND EXPRESSING CHRIST Message Fifty-Five In Revelation (4) The Hidden Manna Scripture Reading: Rev. 2:17; Heb. 9:4; Exo. 16:32-34 I. The hidden manna mentioned in Revelation 2:17 was hidden in a golden pot in the Ark within the Holy of Holies—Heb. 9:4; Exo. 16:32-34: A. Placing the hidden manna in the golden pot signifies that the hidden Christ is con- cealed in the divine nature—Heb. 9:4; Col. 3:1, 3; 2 Pet. 1:4. B. The hidden manna is for those who are intimate with the Lord, those who have forsaken the world and every separation between them and God; they come into the intimacy of God’s presence, and here in this divine intimacy they enjoy the hidden manna in the divine nature—Heb. 9:4; Rev. 2:17. C. Our experience of Christ should not merely be open but also hidden in the Holy of Holies, even in Christ Himself as the Ark, the testimony of God—Heb. 10:19: 1. The golden pot is in the Ark, the Ark is in the Holy of Holies, and the Holy of Holies is joined to our spirit; if we continually touch Christ in our spirit, we will enjoy Him as the hidden manna—4:16; 1 Cor. 6:17. 2. The hidden manna is for the person who remains in the innermost part of God’s dwelling place, abiding in the presence of God in the spirit—2 Tim. -

From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’S Iconic Texts

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2014 From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation James W. Watts, "From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts," pre- publication draft, published on SURFACE, Syracuse University Libraries, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts [Pre-print version of chapter in Ritual Innovation in the Hebrew Bible and Early Judaism (ed. Nathan MacDonald; BZAW 468; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), 21–34.] The builders of Jerusalem’s Second Temple made a remarkable ritual innovation. They left the Holy of Holies empty, if sources from the end of the Second Temple period are to be believed.1 They apparently rebuilt the other furniture of the temple, but did not remake the ark of the cove- nant that, according to tradition, had occupied the inner sanctum of Israel’s desert Tabernacle and of Solomon’s temple. The fact that the ark of the covenant went missing has excited speculation ever since. It is not my intention to pursue that further here.2 Instead, I want to consider how biblical literature dealt with this ritual innovation. -

Lesson Four Joshua 3:1-17 Israel Crosses the River Jordan Key Concept: the LORD Is with Those Who Follow Him

Lesson Four Joshua 3:1-17 Israel crosses the River Jordan Key Concept: The LORD is with those who follow Him. Key Verse: Behold, the ark of the covenant of the LORD of all the earth is crossing over ahead of you into the Jordan. (Joshua 3:11) The Before Word: As Joshua and the Israelites are poised to cross the Jordan River and enter the land promised to their forefathers, GOD wants them to know that He is traveling with them. As you study Joshua 3, look for all the ways GOD shows the people that He is with them and all the ways He shows Joshua that He is with him. As you work through the scripture, record all the ways the LORD assured Joshua and the people that He was with them as they crossed over. This exercise is designed to increase your faith and your ability to see all the ways the LORD is traveling with you! Record all the ways the LORD assured the people and Joshua that He was with them as they crossed over the river. (Record the verse along with the assurance.) Assurances to the People Scripture Assurances to Joshua Scripture Questions for Joshua 3 1. 1. a. Where were the Israelites positioned? (3:1-2) b. For how long did they wait? 1. 2. a. Who was to lead the Israelites across the Jordan River? (3:3-4) b. What were they to carry? c. Why did the officers warn them to keep a distance of 2,000 cubits? d. What significance do you see in this arrangement? The Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:10-22) was constructed of acacia wood, overlaid with gold, covered with golden cherubim, and housed three articles: Aaron’s Rod of Budding, The Stone Tablets of the Law, and a Jar of Manna. -

The Road to Jericho

Although the story is made up by Jesus, the road “from Jerusalem to Jericho” is real. Known as The Bloody Way, the road from Jerusalem to Jericho had a long history of being a perilous journey. © 2021 Living 10:31 Hanna Brinker The Road to Jericho April 15, 2021 “Jesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him and departed, leaving him half dead.” (Luke 10:30) Although the story is made up by Jesus, the road “from Jerusalem to Jericho” is real and would have been understood immediately by his listeners. Known as The Bloody Way, the road from Jerusalem to Jericho had a long history of being a perilous journey famous for attacks by thieves and robbers. The road is about 20 miles long, and was steep, descending about 3000 feet from the Mount of Olives to sea level. It ran through a rocky area with plenty of caves, large boulders and other hiding places that provided robbers a place to lay in wait for defenseless travelers. Although Jesus leaves the man undescribed, the listeners, being Jewish, would naturally assume that he was a Jew. The lawyer, remember, has just asked Jesus ‘who is my neighbor’ – believing that the answer is a ‘fellow Jew.’ Jesus implies that the man who was beaten and robbed is a ‘neighbor’ even in the restricted sense of ‘fellow Jew.’ Since the man is stripped, he is unidentifiable. In Jesus’ day, a person was identified by the way they dressed and the way they spoke – their accent or dialect. -

Deeper Zone PDF Discover and Think

Over the past couple of months we’ve been trying hard not to get too close, haven’t we! Outside our homes we’ve been distancing ourselves from other people by 2 metres to make sure we don’t catch or pass on germs. In our story today the Israelites are told ‘Don’t get too close!’ too, but not to each other, to the Ark of the Covenant. This was because the big gold covered box represented the presence of God, so was very, very holy (special and good). Usually the ark rested in a tent and only the priests ever went past the thick curtain that separated off the area, called the ‘holy of holies’, where it was kept. In today’s story, the ark is carried in front of the people, and they are told to wash and pray before going in sight of it, and then to only go within 900 metres of it. (Take 9 BIG strides and then look back at how far that is. 10 times that is 900 metres.) They really had to treat God’s presence with RESPECT. We still need to treat God with respect - lots of it. But the good news is, we don’t have to think to ourselves, “Don’t get too close”, anymore. We can come as close to God as we want - he loves it when we do! Why? Because 2000 years ago, Jesus made a way for us. Look up this bible passage, to find out what he did: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=matthew+27+%3A+45-56&version=MSG Did you spot it in v 51? Jesus got rid of that thick curtain that was keeping the people away! Now anyone can come into God’s presence - even us! Wordsearch: https://sundayschoolzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/god_stopped_the_jordan_river_word_search.pdf Spot the difference: https://sundayschoolzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/god_stopped_the_jordan_river_spot_the_differences.pdf . -

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museu

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museum Tower of David Herod’s Palace Temple Mount The Temple Mount, in Hebrew: Har HaBáyit, "Mount of the House of God", known to Muslims as the Haram esh-Sharif, "the Noble Sanctuary and the Al Aqsa Compound, is a hill located in the Old City of Jerusalem that for thousands of years has been venerated as a holy site in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike. The present site is a flat plaza surrounded by retaining walls (including the Western Wall) which was built during the reign of Herod the Great for an expansion of the temple. The plaza is dominated by three monumental structures from the early Umayyad period: the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock and the Dome of the Chain, as well as four minarets. Herodian walls and gates, with additions from the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods, cut through the flanks of the Mount. Currently it can be reached through eleven gates, ten reserved for Muslims and one for non-Muslims, with guard posts of Israeli police in the vicinity of each. According to Jewish tradition and scripture, the First Temple was built by King Solomon the son of King David in 957 BCE and destroyed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE – however no substantial archaeological evidence has verified this. The Second Temple was constructed under the auspices of Zerubbabel in 516 BCE and destroyed by the Roman Empire in 70 CE. -

Lesson 10: the Atonement Cover

Lesson 10: The Atonement Cover Read: Exodus 25:17-22, Leviticus 16:11-19 The atonement cover, also called the mercy seat, was like a lid covering the Ark of the Covenant. On top of it stood two cherubim (angels) at the two ends, facing each other. The cherubim, symbols of God’s divine presence and power, were facing downward toward the ark with outstretched wings that covered the atonement cover. The whole structure was beaten out of one piece of pure gold. Discussion: 1. What is the significance of the atonement cover in light of Exodus 25:22 and Leviticus 16:2? The atonement cover was God’s dwelling place and throne in the tabernacle. He sat enthroned between the cherubim (see also 2 Samuel 6:2). It was very holy; it could not be approached lightly. Above the ark and the atonement cover, God appeared as a cloud in His glory. (Additional information: This cloud is sometimes referred to as the Shekinah glory. The word Shekinah, although it does not appear in our English Bibles, has the same roots as the word for tabernacle in Hebrew and refers to the presence of the Lord.) 2. The ark and atonement cover were a symbol of God’s presence and power among His people. Do you recall any incidents regarding the power of the ark in history of the Israelites? There are quite a number of miracles recorded in the Old Testament surrounding the ark: With the presence of the ark, the waters of the River Jordan divided so the Israelites could cross on dry land, and the walls of Jericho fell so that the Israelites could capture it (Joshua 3:14-17, 6:6-21). -

The Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif – Archaeology in a Political Context

The Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif – Archaeology in a Political Context 2017 March 2017 Table of contents >> Introduction 3 Written by: Yonathan Mizrachi >> Part I | The history of the Site: How the Temple Mount became the 0 Researchers: Emek Shaveh Haram al-Sharif 4 Edited by: Talya Ezrahi >> Part II | Changes in the Status of the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif 0 Proof-editing: Noa Granot from the 19th century to the Present Day 7 Graphic Design: Lior Cohen Photographs: Emek Shaveh, Yael Ilan >> Part III | Changes around the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif and the 0 Mapping: Lior Cohen, Shai Efrati, Slava Pirsky impact on the Status Quo 11 >> Conclusion and Lessons 19 >> Maps 20 Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an Israeli NGO working to prevent the politicization of archaeology in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and to protect ancient sites as public assets that belong to members of all communities, faiths and peoples. We view archaeology as a resource for building bridges and strengthening bonds between peoples and cultures. This publication was produced by Emek Shaveh (A public benefit corporation) with the support of the IHL Secretariat, the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs Switzerland (FDFA) the New Israeli Fund and CCFD. Responsibility for the information contained in this report belongs exclu- sively to Emek Shaveh. This information does not represent the opinions of the above mentioned donors. 2 Introduction Immediately after the 1967 War, Israel’s then Defense Minister Moshe Dayan declared that the Islamic Waqf would retain their authority over the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif compound. -

The Hidden Manna of Revelation 2:17

THE HIDDEN MANNA OF REVELATION 2:17 (1) an omer of manna was kept in a jar as a memorial for all generations of Jews to see: Then Moses said, “This is what the LORD has commanded, ‘Let an omerful of it be kept throughout your generations (MRkyEtOrOdVl ’for your generations’), that they may see the bread that I fed you in the wilderness, when I brought you out of the land of Egypt.’” 33 And Moses said to Aaron, “Take a jar (t‰nRx◊nIx) and put an omerful of manna in it, and place it before the LORD, to be kept throughout your generations (MRkyEtOrOdVl ’for your generations’).” 34 As the LORD commanded Moses, so Aaron placed it before the Testimony, to be kept (Exod 16:32–34). t‰nRx◊nˆx “jar, or like receptacle” (BDB) is a hapax legomenon in the Old Testament. It was not a common clay storage jar but a special gold jar (Heb 9:4). The stated intent of storing this manna is not to hide but to show it to all future generations of Jews. It was to be a memorial of God’s providential care and to strengthen the faith of all future generations of God’s people. That is to say, he has, can, and will provide their daily needs no matter how hopeless the situation. It was an historical and doctrinal reminder. Question. How can this jar be placed “before the LORD” (in the ark of the covenant) and still be seen by all the people? Note: this is the only manna that could be stored without spoiling: “and some left part of it until morning, and it bred worms and became foul” (Exod 16:20). -

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem - a View of the Areas That Are Closed to the Public Photos & Edit: Ron Peled 2008

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem - A view of the areas that are closed to the public Photos & Edit: Ron Peled 2008 www.feelJerusalem.com The Temple Mount is open to tourist, but only for an excursion around the open plaza Entrance to the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock, Solomon's Stables and other sitesbelow the Mount itself, are off limits to any non-Muslims. So, let's go in… The structure of the Dome of the Rock is called, in Arabic, Qubat al-Sakhra (which is not the Mosque of Omar, and in fact, not a mosque at all.). It was built in 691 by the Caliph Abd al-Malik (who founded the first Arab town in Israel – Ramla), and is believed to be the oldest and most intact Muslim structure in the Middle East. The interior of the dome is gilded and adorned with beautiful art Gold… The rock in the center of the structure is called the Foundation Stone. According to the Jewish and Muslim faiths, this is where the world was founded. It is where Abraham nearly sacrificed his son Isaac (Mount Moriah), it is where the very center of the Temple, the Holy of Holies, was located (give or take a few feet – but who’s counting?) and according to Islam, from this very place, Mohammad ascended to heaven. According to Islamic tradition, from this very place, Muhammad ascended to Heaven accompanied by the angel Gabriel Below the Foundation Stone is a cave where, according to tradition, Mohammad prayed. The pillars seen in the picture are of secondary use, from the Crusade period when the Templar Knights lodged at the temple mount The Mihrab at the entrance to the cave is in honor of King Solomon and is probably one of the first prayer niches in the Muslim world The al-Aqsa Mosque, above the southern wall of the Temple (Hulda Gates) was first built at the beginning of the 8th century by the Caliph al-Walid. -

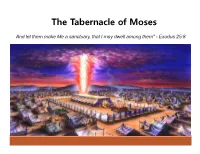

The Tabernacle of Moses

The Tabernacle of Moses And let them make Me a sanctuary, that I may dwell among them" - Exodus 25:8 The Tabernacle of Moses And let them make Me a sanctuary, that I may dwell among them" - Exodus 25:8 The Tabernacle . Over 50 chapters of The Bible reference it . The place where Divinity and humanity came together . 3 Million People . 2/3 size of Rhode Island . Located in the center surrounded by The 12 tribes . Each person gave up something to build . God gave specific construction instructions Exodus 25: 1-9 GOD spoke to Moses: “Tell the Israelites that they are to set aside offerings for me. Receive the offerings from everyone who is willing to give. These are the offerings I want you to receive from them: gold, silver and bronze; also blue, purple, and scarlet yarn ; fine linen; goats’ hair; tanned rams’ skins; acacia wood; lamp oil; spices for anointing oils and for fragrant incense; onyx stones and other stones for setting in the Ephod and the Breast piece. Let them construct a Sanctuary for me so that I can live among them. You are to construct it following the plans I’ve given you, the design for The Dwelling and the design for all its furnishings, follow it closely. Layout of The Tabernacle Materials of Construction Gold (Holy of Holies / Deity) Silver (Redemption/Buy Back) Bronze (Judgement / Brazen Altar) Fine White Linen (Walls of The Tabernacle) Acacia Wood (Indestructible from insects) Goat’s Hair (Covering of The Inner Court) (Scape Goat) Gates of The Tabernacle Yarn (Gates of The Tabernacle) •Blue •Purple •Red John 10:9 “Jesus said I am the gate and whoever enters through me will be saved 7 Elements in The Tabernacle 1. -

The Temple in Heaven: Its Description and Significance

19 The Templein Heaven: Its Descriptionand Significance Jay A. Parry and Donald W. Parry According to several old Jewish traditions, the earthly temple was a copy, counterpart, or mirror image of the heavenly temple. Victor Aptowitzer summarizes the Jewish point of view by writing that [Jewish] literature avers that in heaven there is a temple that is the counterpart of the temple on earth. The same sacrifices are said to be offered there and the same hymns sung as in the earthly temple. Just as the temple below is located in terrestrial Jerusalem so the temple above is located in celestial Jerusalem. 1 Various collections of writings mention the existence of a heavenly temple, including the Old and New Testaments, the Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Talmud, and a host of midrashic 2 materials. Some of the sources provide only a brief description of the temple, while others explain its sig nificance. The goals of this chapter are twofold: First, we will attempt to provide a brief description of the temple in heaven. In this regard, the Revelation of John will prove to be of great assistance, but a number of roughly contempo rary canonical and noncanonical sources will also be help ful. Second, and perhaps more importantly, we will attempt to determine what significance the heavenly temple holds for us. 515 516 JAY A.PARRYANDDONALDW.PARRY Extracanonical References to the Temple in Heaven A number of pseudepigraphic sources make reference to the celestial sanctuary. An explicit reference appears in 1 Enoch, wherein the prophet Enoch ascends to heaven in a vision. The prophet views the magnificent heavenly temple made of crystal.