I Would Save You, but My Boobs Keep Getting in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2019 - No

MEANWHILE FORM FOLLOWS DYSFUNCTION 741.5 NEW EXPERIMENTAL COMICS BY -HUIZENGA —WARE— HANSELMANN- NOVEMBER 2019 - NO. 35 PLUS...HILDA GOES HOLLYWOOD! Davis Lewis Trondheim Hubert Chevillard’s Travis Dandro Aimee de Jongh Dandro Sergio Toppi. The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of Far away from the 3D blockbuster on funny animal comics stands out Galvan follows that pattern, but to emphasize the universality of mentality of commercial comics, a from the madding crowd. As usu- cools it down with geometric their stories as each make their new breed of cartoonists are ex- al, this issue of KE also runs mate- figures and a low-key approach to way through life in the Big City. In panding the means and meaning of rial from the past; this time, it’s narrative. Colors and shapes from contrast, Nickerson’s buildings the Ninth Art. Like its forebears Gasoline Alley Sunday pages and a Suprematist painting overlay a and backgrounds are very de- RAW and Blab!, the anthology Kra- Shary Flenniken’s sweet but sala- alien yet familiar world of dehu- tailed and life-like. That same mer’s Ergot provides a showcase of cious Trots & Bonnie strips from manized relationships defined by struggle between coherence and today’s most outrageous cartoon- the heyday of National Lampoon. hope and paranoia. In contrast to chaos is the central aspect of ists presenting comics that verge But most of this issue features Press Enter to Continue, Sylvia Tommi Masturi’s The Anthology of on avant garde art. The 10th issue work that comes on like W.S. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Pedagogická

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta pedagogická Bakalářská práce VZESTUP AMERICKÉHO KOMIKSU DO POZICE SERIÓZNÍHO UMĚNÍ Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 University of West Bohemia Faculty of Education Undergraduate Thesis THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN COMIC INTO THE ROLE OF SERIOUS ART Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 Tato stránka bude ve svázané práci Váš původní formulář Zadáni bak. práce (k vyzvednutí u sekretářky KAN) Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. V Plzni dne 19. června 2012 ……………………………. Jiří Linda ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank to my supervisor Brad Vice, Ph.D., for his help, opinions and suggestions. My thanks also belong to my loved ones for their support and patience. ABSTRACT Linda, Jiří. University of West Bohemia. May, 2012. The Rise of the American Comic into the Role of Serious Art. Supervisor: Brad Vice, Ph.D. The object of this undergraduate thesis is to map the development of sequential art, comics, in the form of respectable art form influencing contemporary other artistic areas. Modern comics were developed between the World Wars primarily in the United States of America and therefore became a typical part of American culture. The thesis is divided into three major parts. The first part called Sequential Art as a Medium discusses in brief the history of sequential art, which dates back to ancient world. The chapter continues with two sections analyzing the comic medium from the theoretical point of view. The second part inquires the origin of the comic book industry, its cultural environment, and consequently the birth of modern comic book. -

FUN BOOKS During COMIC-CON@HOME

FUN BOOKS during COMIC-CON@HOME Color us Covered During its first four years of production (1980–1984), Gay Comix was published by Kitchen Sink Press, a pioneering underground comic book publisher. Email a photo of you and your finished sheet to [email protected] for a chance to be featured on Comic-Con Museum’s social media! Share with us! @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum SPECIAL EDITION 4 Anagrams of Class Photo Class Photo is a graphic novella by Gay Comix contributor and editor Robert Triptow. Take 3 minutes and write down words of each size by combining and rearranging the letters in the title. After 3 minutes, tally up your score. How’d you do? 4-LETTER WORDS 5-LETTER WORDS 1 point each 2 points each 6-LETTER WORDS 7-LETTER WORDS 8-LETTER WORDS 3 points each 4 points each 6 points each Share with us! @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum SPECIAL EDITION 4 Cross Purpose It’s a crossword and comics history lesson all in one! Learn about cartoonist Howard Cruse, the first editor of the pioneering comic book Gay Comix and 2010 Comic-Con special guest. ACROSS DOWN Share with us! @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum SPECIAL EDITION 4 Dots & Boxes Minimum 2 players. Take turns connecting two dots horizontally or vertically only; no diagonal lines! When you make a box, write your initials in it, then take another turn. Empty boxes are each worth 1 point. Boxes around works by the listed Gay Comix contributors are each worth 2 points. The player with the most points wins! Watch Out Fun Home Comix Alison Vaughn Frick Bechdel It Ain’t Me Babe Trina Robbins & Willy Mendes subGurlz Come Out Jennifer Comix Camper Mary Wings "T.O. -

A Video Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Recipient Art Spiegelman

Inspicio the last laugh Introduction to Art Spiegelman. 1:53 min. Photo & montage by Raymond El- man. Music: My Grey Heaven, from Normalology (1996), by Phillip Johnston, Jedible Music (BMI) A Video Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Recipient Art Spiegelman By Elman + Skye From the Steven Barclay Agency: rt Spiegelman (b. 1948) has almost single-handedly brought comic books out of the toy closet and onto the A literature shelves. In 1992, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his masterful Holocaust narrative Maus— which por- trayed Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. Maus II continued the remarkable story of his parents’ survival of the Nazi regime and their lives later in America. His comics are best known for their shifting graphic styles, their formal complexity, and controver- sial content. He believes that in our post-literate culture the im- portance of the comic is on the rise, for “comics echo the way the brain works. People think in iconographic images, not in holograms, and people think in bursts of language, not in para- graphs.” Having rejected his parents’ aspirations for him to become a dentist, Art Spiegelman studied cartooning in high school and began drawing professionally at age 16. He went on to study art and philosophy at Harpur College before becoming part of the underground comix subculture of the 60s and 70s. As creative consultant for Topps Bubble Gum Co. from 1965-1987, Spie- gelman created Wacky Packages, Garbage Pail Kids and other novelty items, and taught history and aesthetics of comics at the School for Visual Arts in New York from 1979-1986. -

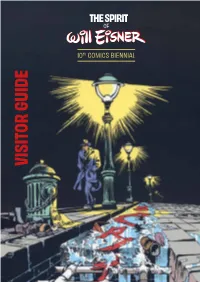

Visitor Guide — Room 1

VISITOR GUIDE — ROOM 1 — THE SPIRIT OF WILL EISNER For its 10th Comics Biennial, the Thomas The one hundred works in this exhibition, Henry Museum is honouring one of the on loan from private collections, present the most influential authors of American comic major stages in the career of an author who books: Will Eisner (1917-2005). Will Eisner was focussed on elevating his discipline left an indelible mark on pop culture with to the rank it deserved, that of an art form The Spirit, a cult series which was to have in its own right. In the complete stories of an impact on the creativity of several The Spirit, Eisner’s very specific narration is generations, from the underground comix there to be discovered (or re-discovered): movement of the 1960s (Robert Crumb, plunge into the very dark atmosphere of Harvey Kurtzman) to the dark comics of the his flagship series, wander through his 1980s (Frank Miller, Alan Moore). theatrical sets and view New York City and the life of its most humble inhabitants from THE THOMAS HENRY MUSEUM Following the end of The Spirit in 1952, Will a different perspective. HAS ADAPTED TO THE CURRENT REGULATIONS RELATING Eisner pondered the theory of his art and TO THE HEALTH CRISIS AND IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. taught a ‘sequential art’ class, at the School of Visual Art in New York. After a long break, THIS EXHIBITION HAS BEEN CREATED IN PARTNERSHIP during which he was creating comics and WITH GALERIE 9e ART (REFERENCES). illustrations for educational purposes, he returned to the forefront of the comic book scene in 1978, inventing a new form of narration: the graphic novel. -

MUNDANE INTIMACIES and EVERYDAY VIOLENCE in CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in Partial Fulfilm

MUNDANE INTIMACIES AND EVERYDAY VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 © Copyright by Kaarina Louise Mikalson, 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Comics in Canada: A Brief History ................................................................................. 7 For Better or For Worse................................................................................................. 17 The Mundane and the Everyday .................................................................................... 24 Chapter outlines ............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 2: .......................................................................................................................... 37 Mundane Intimacy and Slow Violence: ........................................................................... -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies)

European journal of American studies Reviews 2018-4 Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) Christina Douka Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/14166 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Christina Douka, “Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies)”, European journal of American studies [Online], Reviews 2018-4, Online since 07 March 2019, connection on 10 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/14166 This text was automatically generated on 10 July 2021. Creative Commons License Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) 1 Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) Christina Douka 1 Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) 2 London: Bloomsbury, 2018. Pp. x+290 ISBN: 978-1-4742-2784-1 3 Christina Dokou 4 With the exception of Elisabeth El Refaie’s Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures (UP of Mississippi, 2012), which Andrew Kunka cites frequently and with relish in his own survey, this is the only other known full-length monograph study focusing exclusively on the subgenre of autobiographical comics, also identified by other critics and/or creators as “autographics,” “autobiographix,” “autobiofictionalography” or “gonzo literary comics” (Kunka 13-14). Such rarity, even accounting for the relative newness of the scholarly field of Comics Studies, is of even greater value considering that graphic autobiographies constitute a major, vibrant, and—most importantly— mature audience-oriented class of sequential art, recognized by “[m]any comics scholars…as a central genre in contemporary comics” (Kunka 1). As such, this genre has contributed significantly both to the growth of comics as a diverse and qualitative storytelling medium and towards the recognition of said merit by the academic status quo.