AUTOGRAPHY's BIOGRAPHY in a Recent Interview, Alison Bechdel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2019 - No

MEANWHILE FORM FOLLOWS DYSFUNCTION 741.5 NEW EXPERIMENTAL COMICS BY -HUIZENGA —WARE— HANSELMANN- NOVEMBER 2019 - NO. 35 PLUS...HILDA GOES HOLLYWOOD! Davis Lewis Trondheim Hubert Chevillard’s Travis Dandro Aimee de Jongh Dandro Sergio Toppi. The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of Far away from the 3D blockbuster on funny animal comics stands out Galvan follows that pattern, but to emphasize the universality of mentality of commercial comics, a from the madding crowd. As usu- cools it down with geometric their stories as each make their new breed of cartoonists are ex- al, this issue of KE also runs mate- figures and a low-key approach to way through life in the Big City. In panding the means and meaning of rial from the past; this time, it’s narrative. Colors and shapes from contrast, Nickerson’s buildings the Ninth Art. Like its forebears Gasoline Alley Sunday pages and a Suprematist painting overlay a and backgrounds are very de- RAW and Blab!, the anthology Kra- Shary Flenniken’s sweet but sala- alien yet familiar world of dehu- tailed and life-like. That same mer’s Ergot provides a showcase of cious Trots & Bonnie strips from manized relationships defined by struggle between coherence and today’s most outrageous cartoon- the heyday of National Lampoon. hope and paranoia. In contrast to chaos is the central aspect of ists presenting comics that verge But most of this issue features Press Enter to Continue, Sylvia Tommi Masturi’s The Anthology of on avant garde art. The 10th issue work that comes on like W.S. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Pedagogická

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta pedagogická Bakalářská práce VZESTUP AMERICKÉHO KOMIKSU DO POZICE SERIÓZNÍHO UMĚNÍ Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 University of West Bohemia Faculty of Education Undergraduate Thesis THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN COMIC INTO THE ROLE OF SERIOUS ART Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 Tato stránka bude ve svázané práci Váš původní formulář Zadáni bak. práce (k vyzvednutí u sekretářky KAN) Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. V Plzni dne 19. června 2012 ……………………………. Jiří Linda ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank to my supervisor Brad Vice, Ph.D., for his help, opinions and suggestions. My thanks also belong to my loved ones for their support and patience. ABSTRACT Linda, Jiří. University of West Bohemia. May, 2012. The Rise of the American Comic into the Role of Serious Art. Supervisor: Brad Vice, Ph.D. The object of this undergraduate thesis is to map the development of sequential art, comics, in the form of respectable art form influencing contemporary other artistic areas. Modern comics were developed between the World Wars primarily in the United States of America and therefore became a typical part of American culture. The thesis is divided into three major parts. The first part called Sequential Art as a Medium discusses in brief the history of sequential art, which dates back to ancient world. The chapter continues with two sections analyzing the comic medium from the theoretical point of view. The second part inquires the origin of the comic book industry, its cultural environment, and consequently the birth of modern comic book. -

A Video Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Recipient Art Spiegelman

Inspicio the last laugh Introduction to Art Spiegelman. 1:53 min. Photo & montage by Raymond El- man. Music: My Grey Heaven, from Normalology (1996), by Phillip Johnston, Jedible Music (BMI) A Video Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Recipient Art Spiegelman By Elman + Skye From the Steven Barclay Agency: rt Spiegelman (b. 1948) has almost single-handedly brought comic books out of the toy closet and onto the A literature shelves. In 1992, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his masterful Holocaust narrative Maus— which por- trayed Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. Maus II continued the remarkable story of his parents’ survival of the Nazi regime and their lives later in America. His comics are best known for their shifting graphic styles, their formal complexity, and controver- sial content. He believes that in our post-literate culture the im- portance of the comic is on the rise, for “comics echo the way the brain works. People think in iconographic images, not in holograms, and people think in bursts of language, not in para- graphs.” Having rejected his parents’ aspirations for him to become a dentist, Art Spiegelman studied cartooning in high school and began drawing professionally at age 16. He went on to study art and philosophy at Harpur College before becoming part of the underground comix subculture of the 60s and 70s. As creative consultant for Topps Bubble Gum Co. from 1965-1987, Spie- gelman created Wacky Packages, Garbage Pail Kids and other novelty items, and taught history and aesthetics of comics at the School for Visual Arts in New York from 1979-1986. -

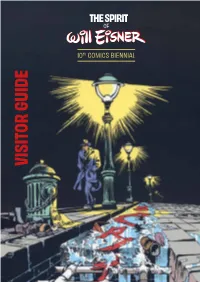

Visitor Guide — Room 1

VISITOR GUIDE — ROOM 1 — THE SPIRIT OF WILL EISNER For its 10th Comics Biennial, the Thomas The one hundred works in this exhibition, Henry Museum is honouring one of the on loan from private collections, present the most influential authors of American comic major stages in the career of an author who books: Will Eisner (1917-2005). Will Eisner was focussed on elevating his discipline left an indelible mark on pop culture with to the rank it deserved, that of an art form The Spirit, a cult series which was to have in its own right. In the complete stories of an impact on the creativity of several The Spirit, Eisner’s very specific narration is generations, from the underground comix there to be discovered (or re-discovered): movement of the 1960s (Robert Crumb, plunge into the very dark atmosphere of Harvey Kurtzman) to the dark comics of the his flagship series, wander through his 1980s (Frank Miller, Alan Moore). theatrical sets and view New York City and the life of its most humble inhabitants from THE THOMAS HENRY MUSEUM Following the end of The Spirit in 1952, Will a different perspective. HAS ADAPTED TO THE CURRENT REGULATIONS RELATING Eisner pondered the theory of his art and TO THE HEALTH CRISIS AND IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. taught a ‘sequential art’ class, at the School of Visual Art in New York. After a long break, THIS EXHIBITION HAS BEEN CREATED IN PARTNERSHIP during which he was creating comics and WITH GALERIE 9e ART (REFERENCES). illustrations for educational purposes, he returned to the forefront of the comic book scene in 1978, inventing a new form of narration: the graphic novel. -

Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies)

European journal of American studies Reviews 2018-4 Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) Christina Douka Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/14166 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Christina Douka, “Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies)”, European journal of American studies [Online], Reviews 2018-4, Online since 07 March 2019, connection on 10 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/14166 This text was automatically generated on 10 July 2021. Creative Commons License Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) 1 Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) Christina Douka 1 Andrew J. Kunka, Autobiographical Comics. (Bloomsbury Comics Studies) 2 London: Bloomsbury, 2018. Pp. x+290 ISBN: 978-1-4742-2784-1 3 Christina Dokou 4 With the exception of Elisabeth El Refaie’s Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures (UP of Mississippi, 2012), which Andrew Kunka cites frequently and with relish in his own survey, this is the only other known full-length monograph study focusing exclusively on the subgenre of autobiographical comics, also identified by other critics and/or creators as “autographics,” “autobiographix,” “autobiofictionalography” or “gonzo literary comics” (Kunka 13-14). Such rarity, even accounting for the relative newness of the scholarly field of Comics Studies, is of even greater value considering that graphic autobiographies constitute a major, vibrant, and—most importantly— mature audience-oriented class of sequential art, recognized by “[m]any comics scholars…as a central genre in contemporary comics” (Kunka 1). As such, this genre has contributed significantly both to the growth of comics as a diverse and qualitative storytelling medium and towards the recognition of said merit by the academic status quo. -

Feminist (And/As) Alternative Media Practices in Women’S Underground Comix in the 1970S1

Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s1 Abstract: The American underground comix scene in general, and women’s comix that flourished as a part of that scene in the 1970s in particular, grew out of and in response to the mainstream American comics scene, which, from its “Golden Age” to the 1970s, had been ruled and construed in accordance with commercial business practices and “assembly-line” processes. This article discusses underground comix created by women in the 1970s in the wider context of alternative and second-wave feminist media practices. I explain how women’s comix used “activist aesthetics” and parodic poetics, combining a radical political and social message with independent publishing and distributive networks. Keywords: American comics, American comix, women’s comix, feminist art and theory, media practices Introduction Toughly mainly associated with popular culture, mass production, and thus consumerism, the history of comics also intertwines with the history of the American counterculture and feminism. In the present article, I examine women’s underground comix from the 1970s as a product and an integral element of a complex and dynamic network of historical, cultural, and social factors, including the mainstream comics industry, men’s underground comix, and alternative media practices, demonstrating how the media practices adopted by female comix authors were used to promote the ideals of second-wave feminism. As Elke Zobl and Ricarda Drüeke point out in Feminist Media, “[u]sing media to transport their messages, to disrupt social orders and to spin novel social processes, feminists have long recognized the importance of self-managed, alternative media” (11). -

Newfangles 31 1970-02

I Number 31, February 1970. Monthly from Don & Maggie Thompson, 8786 Hendricks Rd., Mentor, Ohio 44060, for 100 a copy, 10 for $1, free copies for news, cartoons, title logos or other valuable considerations. Back issues (24 25 27-30) for 100 each. V-liile your wallet is out, we have a few copies left of a checklist of Dell ’’special series” titles (plus some others) at $1, plus 100 for a planned corrections list; and How to Sur vive Comics Fandom at 200. Circulation of Newfangles this issue: 307. No ad sheets again this Cartoon: month, but our giant Jefferson Hamill cellar-cleaning sale will be back soon. REISINGER RETIRES: Mort Reisinger, editor of Superman, Superbov, Action, Adventure, Lois Lane, Jimmy Olsen and 7. or Id ’ s Finest Comics, is retiring. His books are to be divided among the other National-DC editors. Details when we get them. A full rundown probably will be in the next Comic Reader. CIRCULATION figures are appearing (we need help on this: we never see the Archie, most DC, Charlton or Dennis the Menace books -- if you do, how about passing on the total avg. paid circulation figures?). In general, circulations are down for DC, holding pretty steady for Marvel, climbing for Charlton. Y.e discern no trend for sure with Gold Key, but it seems to be downward. Superman lost 124,416 from the 1969-published figure; Batman is down 177,668; World’s Finest is off 113,497; Tarzan is off 91,778; Jimmy Olsen lost 81,325. By remaining steady while others lost (down 951 from last year), Spider-Man has moved above Rorld1s Finest, Batman and Tarzan in circulation. -

Newfangles 37 1970-07

NEWFANGLES 37 from Don & Jfeggie Thompson, 8786 Hendricks Rd., Mentor, Ohio 44060. 100 a copy- through #40, 200 there after (see inside for an explanation). Back issues (24 29 30 33 35) @100. Our circulation is 437, up 100 from last month, almost entirely due to mention in RBCC. Our title logo this month is by Jim Warren, who is a good man. The Dick Tracy cartoon inside somewhere is bv Mike Britt. 373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737 2000/ attend NY Comicon. That was paid attendance as of the first day; most estimates run considerably higher. There were some complaints (traders all over the halls, blocking traffic; hotel goons challenging anyone not wearing convention identification — one goon, really overly officious, challenged Guest of Honor Bill Everett even though Everett was standing by a huge photo of himself at the time) but most seemed to think it was a good convention. We only have a handful of reports so far. Sol Brodsky has quit Marvel to form his own publishing firm (not comics). John Verpoorten is replacing him as Marvel’s production manager. Gary Friedrich has quit Marvel, too, again. He did the first part of a Daredevil 2-parter based on the Chicago 7, quit without notice between installments. Challengers of the Unknown dies with #77, though one report said the Deadman issue did so well the book might be renewed with Deadman on a more-or-less-regular basis. Silver Surfer died with 18, the Kirby issue; Trimpe did the first page, was working on the second for his first issue when the book was killed. -

“We're Not Rated X for Nothin', Baby!”

CORSO DI DOTTORATO IN “LE FORME DEL TESTO” Curriculum: Linguistica, Filologia e Critica Ciclo XXXI Coordinatore: prof. Luca Crescenzi “We’re not rated X for nothin’, baby!” Satire and Censorship in the Translation of Underground Comix Dottoranda: Chiara Polli Settore scientifico-disciplinare L-LIN/12 Relatore: Prof. Andrea Binelli Anno accademico 2017/2018 CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 1: FROM X-MEN TO X-RATED ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 1. “DEPRAVITY FOR CHILDREN – TEN CENTS A COPY!” ......................................................... 12 1.1. A Nation of Stars and Comic Strips ................................................................................................................... 12 1.2. Comic Books: Shades of a Golden Age ............................................................................................................ 24 1.3. Comics Scare: (Self-)Censorship and Hysteria ................................................................................................. 41 Chapter 2. “HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN?”: RISE AND FALL OF A COUNTERCULTURAL REVOLUTION ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Feminist (And/As) Alternative Media Practices in Women’S Underground Comix in the 1970S1

Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s1 Abstract: The American underground comix scene in general, and women’s comix that flourished as a part of that scene in the 1970s in particular, grew out of and in response to the mainstream American comics scene, which, from its “Golden Age” to the 1970s, had been ruled and construed in accordance with commercial business practices and “assembly-line” processes. This article discusses underground comix created by women in the 1970s in the wider context of alternative and second-wave feminist media practices. I explain how women’s comix used “activist aesthetics” and parodic poetics, combining a radical political and social message with independent publishing and distributive networks. Keywords: American comics, American comix, women’s comix, feminist art and theory, media practices Introduction Toughly mainly associated with popular culture, mass production, and thus consumerism, the history of comics also intertwines with the history of the American counterculture and feminism. In the present article, I examine women’s underground comix from the 1970s as a product and an integral element of a complex and dynamic network of historical, cultural, and social factors, including the mainstream comics industry, men’s underground comix, and alternative media practices, demonstrating how the media practices adopted by female comix authors were used to promote the ideals of second-wave feminism. As Elke Zobl and Ricarda Drüeke point out in Feminist Media, “[u]sing media to transport their messages, to disrupt social orders and to spin novel social processes, feminists have long recognized the importance of self-managed, alternative media” (11).