Identity and Form in Alternative Comics, 1967 – 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a Close Reading of Contemporary Graphic Novels

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a close reading of contemporary graphic novels Abstract: The study offers an alternative analytical framework for thinking about the contemporary graphic novel as a dynamic area of visual art practice. Graphic narratives are placed within the broad, open-ended territory of investigative drawing, rather than restricted to a special category of literature, as is more usually the case. The analysis considers how narrative ideas and energies are carried across specific examples of work graphically. Using analogies taken from recent academic debate around translation, aspects of Performance Studies, and, finally, common categories borrowed from linguistic grammar, the discussion identifies subtle varieties of creative processing within a range of drawn stories. The study is practice-based in that the questions that it investigates were first provoked by the activity of drawing. It sustains a dominant interest in practice throughout, pursuing aspects of graphic processing as its primary focus. Chapter 1 applies recent ideas from Translation Studies to graphic narrative, arguing for a more expansive understanding of how process brings about creative evolutions and refines directing ideas. Chapter 2 considers the body as an area of core content for narrative drawing. A consideration of elements of Performance Studies stimulates a reconfiguration of the role of the figure in graphic stories, and selected artists are revisited for the physical qualities of their narrative strategies. Chapter 3 develops the grammatical concept of tense to provide a central analogy for analysing graphic language. The chapter adapts the idea of the graphic „confection‟ to the territory of drawing to offer a fresh system of analysis and a potential new tool for teaching. -

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 19 No. 14, October 9, 1986

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 10-9-1986 Central Florida Future, Vol. 19 No. 14, October 9, 1986 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 19 No. 14, October 9, 1986" (1986). Central Florida Future. 659. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/659 Weather: There's alot of sun behind those rain clouds Thursday, October 9, 1986 The Central Florida Future Volume 19 Number 14 - University of Central Florida/Orlando Twelve pages BOR forces credit Committee may hike union to re·locate health fee by Desiree McCartney Department of University NEWS EDITOR Relations, located next to the Fee could rise credit union's old location, is cramped due to lack of space. from 524 to 530 The UCF Federal Credit The move will allow the Union re-located to th~ department to be more spread Washington T. Student out. by Tim Ball Services Building last Hyde explained the move CENTRAL FLORIDA FUTURE Monday because UCF's does have some benefits. He Board of Regents policy said the credit union will now The Health Fee Committee involving space allocation. -

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011 Table of Contents: Fact Sheet 3 Why I Chose Top Shelf 4 Interview with Chris Staros 5 Book Review: Blankets by Craig Thompson 12 2 Fact Sheet: Top Shelf Productions Web Address: www.topshelfcomix.com Founded: 1997 Founders: Brett Warnock & Chris Staros Editorial Office Production Office Chris Staros, Publisher Brett Warnock, Publisher Top Shelf Productions Top Shelf Productions PO Box 1282 PO Box 15125 Marietta GA 30061-1282 Portland OR 97293-5125 USA USA Distributed by: Diamond Book Distributors 1966 Greenspring Dr Ste 300 Timonium MD 21093 USA History: Top Shelf Productions was created in 1997 when friends Chris Staros and Brett Warnock decided to become publishing partners. Warnock had begun publishing an anthology titled Top Shelf in 1995. Staros had been working with cartoonists and had written an annual resource guide The Staros Report regarding the best comics in the industry. The two joined forces and shared a similar vision to advance comics and the graphic novel industry by promoting stories with powerful content meant to leave a lasting impression. Focus: Top Shelf publishes contemporary graphic novels and comics with compelling stories of literary quality from both emerging talent and known creators. They publish all-ages material including genre fiction, autobiographical and erotica. Recently they have launched two apps and begun to spread their production to digital copies as well. Activity: Around 15 to 20 books per year, around 40 titles including reprints. Submissions: Submissions can be sent via a URL link, or Xeroxed copies, sent with enough postage to be returned. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Gypsum in California

TN 2.4 C3 A3 i<o3 HK STATE OP CAlIFOa!lTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES msmtBmmmmmmmmmaam GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA BULLETIN 163 1952 aou DIVl^ON OF MNES fZBar SDODSia sxh lasncisco ^"^^^^^nBM^^MMa^HBi«iaMa«NnMaMHBaaHB^HaHaa^^HHMi«nfl^HaMHiBHHHMauuHJin««aHiav^aMaHHaHHB«auKaiaMi^^M«ni^Maai^iMMWi^iM^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS STATE OF CALIFORNIA EARL WARREN, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES WARREN T. HANNUM, Director DIVISION OF MINES FERRY BUILDING, SAN FRANCISCO 11 OLAF P. JENKINS, Chief San Francisco BULLETIN 163 September 1952 GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA By WILLIAM E. VER PLANCK LIBRARY UNTXERollY OF CAUFC^NIA DAVIS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To IIlS EXCELLKNCY, TlIK IIONORAHLE EauL AVaRREN Governor of the State of California Dear Sir: I have the lionor to transmit herewitli liuUetiii 163, Gyj)- sinn in California, prepared under tlie direetion of Ohif P. Jenkins, Chief of the Division of ]\Iines. Gypsum represents one of the important non- metallic mineral commodities of California. It serves particularly two of California's most important industries, aprieulture and construction. In Bulletin 163 the author, W. p]. Xev Phinek, a member of the staff of the Division of Mines, has prepared a comprehensive treatise cover- ing all phases of the subject : history of the industry, geologic occurrence and origin of tlie minoi-al, mining, i)rocessing and marketing of the com- modity. Specific g3'psum i)roperties Avere examined and mapped. The report is profusely illustrated by maps, charts and photographs. In the preparation of the report it was necessary for the author to make field investigations, laboratory and library studies, and to determine how the mineral is used in industry as Avell as how it occurs in nature and how it is mined. -

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

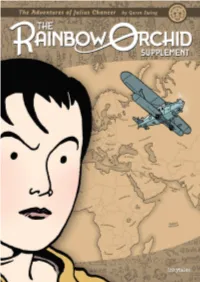

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea. -

Report on Micro Data, Sorted by Title

English Language Graphic Novels Winners and Nominations of Comics and Graphic Novels Awards up to 2004 (list sorted first by title) Prepared by Olivier Charbonneau [email protected] Concordia University Data current as of May 18, 2004 PS. Please feel free to use and circulate this list – as long as the person using or receiving it does not use it for commercial purposes (selecting books for a library is OK) and agrees to send me a thank you letter at the following address: Olivier Charbonneau, Webster Library, room LB-279 Concordia University 1400 de Maisonneuve Blvd. W. Montreal, Quebec, H3G 1M8 Page 1 of 56 Title Publisher Wins Nominations 100 Unknown 1 Workman, John letterer 100 BulletDC 4 5 Azzarello, Brian writer Johnson, Dave cover 2002-2003 Risso, Eduardo artist 1001 Nights of BacchusDark Horse Comics 1 Schutz, Diana editor 1963 Image 2 Moore, Alan 20 Nude Dancers 20Tundra 1 Martin, Mark 20/20 VisionsDC/Vertigo 1 Alonso, Axel editor Berger, Karen editor 300Dark Horse Comics 2 2 Miller, Frank Varley, Lynn colorist 32 Stories Drawn & Quarterly 1 Tomine, Adrian A Contract with GodDC 2 Eisner, Will A Decade of Dark HorseDark Horse Comics 1 Stradley, Randy editor A History of ViolenceParadox 1 Wagner, John A Jew in Communist PragueNBM 1 4 Giardino, Vittorio Nantier, Terry editor A Small KillingVG Graphics/Dark Horse 1 1 Moore, Alan Zarate, Oscar A1Atomeka 1 2 Elliott, Dave editor Abraham StonePlatinum/Malibu 2 Kubert, Joe Page 2 of 56 Title Publisher Wins Nominations Acid Bath CaseKitchen Sink Press 1 Schreiner, Dave editor