Independent Office of Evaluation Nepal Country Programme Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONNECT Component Review

CONNECT component review CONNECT component review Date: 4 May 2020 Authors: Gordon Freer and Edward Hedley Submitted by Itad Itad 4 May 2020 CONNECT component review Acknowledgements The review team acknowledges the support of the Connect programme team in providing documentation and helping the team to arrange interviews. The review team also expresses thanks to our field team in conducting interviews and collecting data in the field. Disclaimer The views expressed in this report are those of the evaluators. They do not represent those of Connect or of any of the individuals and other organisations referred to in the report. ‘Itad’ and the tri-colour triangles icon are a registered trademark of ITAD Limited. Itad 4 May 2020 i CONNECT component review Contents List of acronyms iii 1. Introduction and scope 1 1.1. CONNECT component background 1 1.2. Review purpose 1 1.3. Review methodology 1 1.4. Review limitations 2 1.5. Structure of the report 2 2. Theoretical framework Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.1. The M4P Theory of Change 3 2.2. The CONNECT Theory of Change 4 2.3. Intervention Theories of Change 5 2.4. Commentary on intervention design 6 3. Findings 8 3.1. Relevance 8 3.2. Effectiveness: were the interventions effective in promoting changes to practice? 11 3.3. Impact: did the changes have value for the beneficiaries? 13 3.4. Sustainability: Are the changes likely to be implemented in the future? 15 4. Conclusion 18 5. Lessons and recommendations 19 List of references 21 Table of respondents 22 Annex A: Case study – Belpata Dairy -

Some Notes on Nepali Castes and Sub-Castes—Jat and Thar

SOME NOTES ON NEPALI CASTES AND SUB-CASTES- JAT AND THAR. - Suresh Singh This paper attempts to make a re-presentation of evolution and construction of Jat and Thar system among the Parbatya or hill people of Nepal. It seeks to expose the reality behind the myth that the large number of Aryans migrated from Indian plains due to Muslim invasion and conquered to become the rulers in Nepal, and the Mongoloids were the indigenous people. It also seeks to show the construction and reconstruction of identity of the different castes (Jats) and subcastes (Thars). The Nepalese history is lost in legends and fables. Archaeological data, which might shed light on the early years, are practically nonexistent or largely unexplored, because the Nepalese Government has not encouraged such research within its borders. However, there seem to be a number of sites that might yield valuable find, once proper excavation take place. Another problem seems to be that history writing is closely connected with the traditional conception of Nepali historiography, constructed and intervened by the efforts of the ruling elite. Many of the written documents have been re-presented to legitimatize the ruling elite’s claim to power. As it is well known from political history, the social history, too, becomes an interpretation from the view of the Kathmandu valley, and from the Indian or alleged Indian immigrants and priestly class. It is difficult to imagine, that Aryans came to Nepal in greater numbers about 600 years ago, and because of their mental superiority and their noble character, they were asked by the people to become the rulers of their small states. -

In Nepal : Citizens’ Perspectives on the Rule of Law and the Role of the Nepal Police

Calling for Security and Justice in Nepal : Citizens’ Perspectives on the Rule of Law and the Role of the Nepal Police Author Karon Cochran-Budhathoki Editors Shobhakar Budhathoki Nigel Quinney Colette Rausch With Contributions from Dr. Devendra Bahadur Chettry Professor Kapil Shrestha Sushil Pyakurel IGP Ramesh Chand Thakuri DIG Surendra Bahadur Shah DIG Bigyan Raj Sharma DIG Sushil Bar Singh Thapa Printed at SHABDAGHAR OFFSET PRESS Kathmandu, Nepal United States Institute of Peace National Mall at Constitution Avenue 23rd Street NW, Washington, DC www.usip.org Strengthening Security and Rule of Law Project in Nepal 29 Narayan Gopal Marg, Battisputali Kathmandu, Nepal tel/fax: 977 1 4110126 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] © 2011 United States Institute of Peace All rights reserved. © 2011 All photographs in this report are by Shobhakar Budhathoki All rights reserved. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. CONTENTS Foreword by Ambassador Richard H. Solomon, President of the United States Institute of Peace VII Acknowledgments IX List of Abbreviations XI Chapter 1 Summary 1.1 Purpose and Scope of the Survey 3 1.2 Survey Results 4 1.2.1 A Public Worried by Multiple Challenges to the Rule of Law, but Willing to Help Tackle Those Challenges 4 1.2.2 The Vital Role of the NP in Creating a Sense of Personal Safety 4 1.2.3 A Mixed Assessment of Access to Security 5 1.2.4 Flaws in the NP’s Investigative Capacity Encourage “Alternative -

Agastya Nadi Samhita

CHAPTER NO. 1 Sri. Agastya Naadi Samhita A mind - boggling Miracle In today’s world of science, if just from the impression of your thumb somebody accurately tells you, your name, the names of your mother, father, husband/wife, your birth-date, month, age etc. what would you call such prediction? Would you regard it as an amazing divination or as black magic? No, it is neither black magic nor a hand trick. Such prediction, which defies all logic and boggles one’s mind, forms the subject-matter of the Agastya Naadi. Those predictions were visualised at different places by various ancient Sages, with their divine insight and factually noted by their chosen disciples, thousands of years ago, to be handed down from generation to generation. This great work makes us realize the limitations of human sciences. That great compilation predicting the future of all human beings born or yet to be born, eclipses the achievements of all other sciences put together! Naadi is a collective name given to palm-leaf manuscripts dictated by ancient sages predicting the characteristics, family history, as well as the careers of innumerable individuals. The sages (rishis), who dictated those Naadis, were gifted with such a remarkable foresight – that they accurately foretold the entire future of all mankind. Many scholars in different parts of India have in their safekeepings several granthas (volumes) of those ancient palm-leaf manuscripts dictated by the great visualizing souls, alias sages such as Bhrugu, Vasistha, Agastya, Shukra, and other venerable saints. I had the good-fortune to consult Sri. Agastya Naadi predictions. -

{PDF} World Record Paintings of Lord Hanuman Ebook, Epub

WORLD RECORD PAINTINGS OF LORD HANUMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amrita Gupta | 118 pages | 01 Jan 2017 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781542852432 | English | none World Record Paintings of Lord Hanuman PDF Book Notification Center. In our Hindu scriptures we find countless references to powerful beings in the previous ages. Sandeep palyal on August 14, at am. Chattarpur Temple Hanuman ft Hanuman Statue in Chattarpur Temple complex is located in a down town area in south of Delhi, It is the second largest temple complex in India and one of the largest in the world. Explore our online art gallery and grab your choice of painting or portraits or craft. He is generally depicted as a man with the face of a monkey and a long tail. Even the Bible gives mention to the giants who walked the earth in ancient times:. Having become a master of all that he set out to learn, it was now time for Hanuman to pay for his education guru-dakshina. However, it turned out to be an empty promise and was never materialized. Very well composed. Total redeemable TimesPoints 0. Something went wrong. It was decreed that Hanuman would remain blissfully unaware of his own prowess, unless, during the course of a meritorious deed, his memory would remind him of his superhuman ability. Gladiator Drawing. Mickey Mouse Head Drawing. Hanuman's quest is suggestive of a much deeper symbolism than a mere search for the 'physical' Sita At last the monkeys confronted Mandodari, the chief wife of Ravana. Predictably there was panic in the cosmos. -

Micro Cottage and Small Entrepreneur Refinancing

l;4fy{ a}+s lnld6]8 != n3' 3/]n tyf ;fgf pBd shf{ s| g zfvf C0fLsf] gfd k||b]z s| g zfvf C0fLsf] gfd k||b]z . 1 Fikkal Sarita Pradhan 1 2101 JANAKPU CHAND TAILORS 2 2 Fikkal Navin Katuwal 1 2102 HETAUD RADHA SUPPLIERS Bagmati 3 Fikkal Rita Shrestha 1 2103 AAMCHO HIMAL FENCY KAPADA PASAL 1 4 Fikkal Pramesh Lamichhane 1 2104 SURKHET TIKA KHADYA TATHA KIRANAPASAL Karnali 5 RAJMARGA CHOWK KANKAI SUPPLIERS 1 2105 DHANGA KARUNA ELECTRONICS Sudurpashchim 6 Sindhuli unique electronic pasal 4 2106 DHANGA ANKIT NASTA PASAL Sudurpashchim 7 Sindhuli Kamal Bahadur khadka 5 2107 BUDIGAN TU FURNITURE UDHOG Sudurpashchim 8 Farsatikar New Kharel Order Suppliers 5 2108 BUDDHA SHUBHECHCHHA FANCY PASAL Gandaki 9 Taplejung Chandani Hotel 1 2109 TULSIPU NEW DANGI PLUMBINGSUPPLIERS 5 10 Taplejung Tej Bir Limbu 1 2110 HETAUD AMRITA KIRANA AND COLDSTORES Bagmati 11 Taplejung Dipak Gurung 1 2111 YASHOD SHUBHAM MOBILE CENTER 5 12 Taplejung Ganga Bahadur Limbu 1 2112 GADHI RAMU WORKSHOP 1 13 Taplejung Som Bimali 1 2113 DHANGA SANJAY AND YAMAN TRADERS Sudurpashchim 14 Taplejung Hari Kumar Limbu 1 2114 GOKULG G.N. ELECTRONICS AND MOBILECENTER Bagmati 15 Taplejung Chhowang Sherpa 1 2115 AAMCHO LOK BAHADUR KIRANA PASAL 1 16 Taplejung Gopal Neupane 1 2116 GHORAHI NEW SABINA HOTEL 5 17 Birauta Prashidddi Tours and Travels Pvt Ltd. Gandaki 2117 BUDIGAN NAUBIS GENERAL STORE Sudurpashchim 18 Chandragadi Sagarmatha Treders 1 2118 BIRATCH KANCHHA BAHUUDESHYAKRISHI FIRM 1 19 Chandragadi Hotel Grindland 1 2119 AAMCHO NANGANU NUYAHANG TRADERS 1 20 Chandragadi Bina books and Stationery 1 2120 AAMCHO SAKENWA PHALPHUL TA. -

List of Active Agents

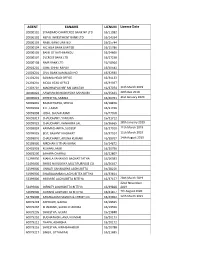

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal

UNEQUAL CITIZENS UNEQUAL37966 Public Disclosure Authorized CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Caste and Ethnic Exclusion Gender, THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development SUMMARY BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Tel.: 5542980 Complex Fax: 5542979 Durbar Marg Public Disclosure Authorized Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk Public Disclosure Authorized DFID Development International Department For ISBN 99946-890-0-2 9 799994 689001 > BANK WORLD THE Public Disclosure Authorized A Kathmandu businessman gets his shoes shined by a Sarki. The Sarkis belong to the leatherworker subcaste of Nepal’s Dalit or “low caste” community. Although caste distinctions and the age-old practices of “untouchability” are less rigid in urban areas, the deeply entrenched caste hierarchy still limits the life chances of the 13 percent of Nepal’s population who belong to the Dalit caste group. UNEQUAL CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal SUMMARY THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Complex Tel.: 5542980 Durbar Marg Fax: 5542979 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk A copublication of The World Bank and the Department For International Development, U.K. -

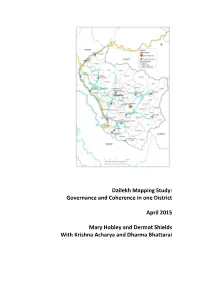

2015 Dailekh Mapping Study on Governance and Coherence

Dailekh Mapping Study: Governance and Coherence in one District April 2015 Mary Hobley and Dermot Shields With Krishna Acharya and Dharma Bhattarai Table of Contents Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ 4 Executive summary .............................................................................................................. 6 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1 Approach ............................................................................................................. 14 1.2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 15 2. Framework for mapping ............................................................................................. 18 2.1 Structures ............................................................................................................. 18 2.1.1 Core Ministries ......................................................................................................... 18 2.1.2 Sub-national organisation and structure ................................................................. 19 2.1.3 Sector ministries ...................................................................................................... 20 2.2 Key concepts ........................................................................................................ -

Hanuman Chalisa in English and with Description in English Page 1 of 4

Hanuman Chalisa In English And With Description In English Page 1 of 4 Hanuman Chalisa In English And With Description In English Shri Guru Charan Saroj Raj After cleansing the mirror of my mind with the pollen Nij mane mukure sudhar dust of holy Guru's Lotus feet. I Profess the pure, Varnao Raghuvar Vimal Jasu untainted glory of Shri Raghuvar which bestows the four- Jo dayaku phal char fold fruits of life.(Dharma, Artha, Kama and Moksha). Budhi Hin Tanu Janike Fully aware of the deficiency of my intelligence, I Sumirau Pavan Kumar concentrate my attention on Pavan Kumar and humbly Bal budhi Vidya dehu mohe ask for strength, intelligence and true knowledge to Harahu Kalesa Vikar relieve me of all blemishes, causing pain. Jai Hanuman gyan gun sagar Victory to thee, O'Hanuman! Ocean of Wisdom-All Jai Kapis tihun lok ujagar hail to you O'Kapisa! (fountain-head of power,wisdom and Shiva-Shakti) You illuminate all the three worlds (Entire cosmos) with your glory . Ram doot atulit bal dhama You are the divine messenger of Shri Ram. The Anjani -putra Pavan sut nama repository of immeasurable strength, though known only as Son of Pavan (Wind), born of Anjani. Mahavir Vikram Bajrangi With Limbs as sturdy as Vajra (The mace of God Indra) Kumati nivar sumati Ke sangi you are valiant and brave. On you attends good Sense and Wisdom. You dispel the darkness of evil thoughts. Kanchan varan viraj subesa Your physique is beautiful golden coloured and your dress Kanan Kundal Kunchit Kesa is pretty. You wear ear rings and have long curly hair. -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O. -

Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation

Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation Karnali Province Government Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment Surkhet, Nepal Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation Karnali Province Government Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment Surkhet, Nepal Copyright: © 2020 Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Karnali Province Government, Surkhet, Nepal The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of Ministry of Tourism, Forest and Environment, Karnali Province Government, Surkhet, Nepal Editors: Krishna Prasad Acharya, PhD and Prakash K. Paudel, PhD Technical Team: Achyut Tiwari, PhD, Jiban Poudel, PhD, Kiran Thapa Magar, Yogendra Poudel, Sher Bahadur Shrestha, Rajendra Basukala, Sher Bahadur Rokaya, Himalaya Saud, Niraj Shrestha, Tejendra Rawal Production Editors: Prakash Basnet and Anju Chaudhary Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Acharya, K. P., Paudel, P. K. (2020). Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation. Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Karnali Province Government, Surkhet, Nepal Cover photograph: Tibetan wild ass in Limi valley © Tashi R. Ghale Keywords: biodiversity, conservation, Karnali province, people-wildlife nexus, biodiversity profile Editors’ Note Gyau Khola Valley, Upper Humla © Geraldine Werhahn This book “Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation”, is prepared to consolidate existing knowledge about the state of biodiversity in Karnali province. The book presents interrelated dynamics of society, physical environment, flora and fauna that have implications for biodiversity conservation.