Chapter 2 Atoms, Molecules, and Ions 67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IR-3 Elements and Groups of Elements (March 04)

1 IR-3 Elements and Groups of Elements (March 04) CONTENTS IR-3.1 Names and symbols of atoms IR-3.1.1 Systematic nomenclature and symbols for new elements IR-3.2 Indication of mass, charge and atomic number using indexes (subscripts and superscripts) IR-3.3 Isotopes IR-3.3.1 Isotopes of an element IR-3.3.2 Isotopes of hydrogen IR-3.4 Elements (or elementary substances) IR-3.4.1 Name of an element of infinite or indefinite molecular formula or structure IR-3.4.2 Name of allotropes of definite molecular formula IR-3.5 Allotropic modifications IR-3.5.1 Allotropes IR-3.5.2 Allotropic modifications constituted of discrete molecules IR-3.5.3 Crystalline allotropic modifications of an element IR-3.5.4 Solid amorphous modifications and commonly recognized allotropes of indefinite structure IR-3.6 Groups of elements IR-3.6.1 Groups of elements in the Periodic Table and their subdivisions IR-3.6.2 Collective names of groups of like elements IR-3.7 References IR-3.1 NAMES AND SYMBOLS OF ATOMS The origins of the names of some chemical elements, for example antimony, are lost in antiquity. Other elements recognised (or discovered) during the past three centuries were named according to various associations of origin, physical or chemical properties, etc., and more recently to commemorate the names of eminent scientists. In the past, some elements were given two names because two groups claimed to have discovered them. To avoid such confusion it was decided in 1947 that after the existence of a new element had been proved beyond reasonable doubt, discoverers had the right to IUPACsuggest a nameProvisional to IUPAC, but that only Recommendations the Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (CNIC) could make a recommendation to the IUPAC Council to make the final Page 1 of 9 DRAFT 2 April 2004 2 decision. -

Neutron Stars

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide Neutron Stars Ordinary matter, or the stuff we and everything around us is made of, consists largely of empty space. Even a rock is mostly empty space. This is because matter is made of atoms. An atom is a cloud of electrons orbiting around a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons. The nucleus contains more than 99.9 percent of the mass of an atom, yet it has a diameter of only 1/100,000 that of the electron cloud. The electrons themselves take up little space, but the pattern of their orbit defines the size of the atom, which is therefore 99.9999999999999% Chandra Image of Vela Pulsar open space! (NASA/PSU/G.Pavlov et al. What we perceive as painfully solid when we bump against a rock is really a hurly-burly of electrons moving through empty space so fast that we can't see—or feel—the emptiness. What would matter look like if it weren't empty, if we could crush the electron cloud down to the size of the nucleus? Suppose we could generate a force strong enough to crush all the emptiness out of a rock roughly the size of a football stadium. The rock would be squeezed down to the size of a grain of sand and would still weigh 4 million tons! Such extreme forces occur in nature when the central part of a massive star collapses to form a neutron star. The atoms are crushed completely, and the electrons are jammed inside the protons to form a star composed almost entirely of neutrons. -

The Moedal Experiment at the LHC. Searching Beyond the Standard

126 EPJ Web of Conferences , 02024 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201612602024 ICNFP 2015 The MoEDAL experiment at the LHC Searching beyond the standard model James L. Pinfold (for the MoEDAL Collaboration)1,a 1 University of Alberta, Physics Department, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 0V1, Canada Abstract. MoEDAL is a pioneering experiment designed to search for highly ionizing avatars of new physics such as magnetic monopoles or massive (pseudo-)stable charged particles. Its groundbreaking physics program defines a number of scenarios that yield potentially revolutionary insights into such foundational questions as: are there extra dimensions or new symmetries; what is the mechanism for the generation of mass; does magnetic charge exist; what is the nature of dark matter; and, how did the big-bang develop. MoEDAL’s purpose is to meet such far-reaching challenges at the frontier of the field. The innovative MoEDAL detector employs unconventional methodologies tuned to the prospect of discovery physics. The largely passive MoEDAL detector, deployed at Point 8 on the LHC ring, has a dual nature. First, it acts like a giant camera, comprised of nuclear track detectors - analyzed offline by ultra fast scanning microscopes - sensitive only to new physics. Second, it is uniquely able to trap the particle messengers of physics beyond the Standard Model for further study. MoEDAL’s radiation environment is monitored by a state-of-the-art real-time TimePix pixel detector array. A new MoEDAL sub-detector to extend MoEDAL’s reach to millicharged, minimally ionizing, particles (MMIPs) is under study Finally we shall describe the next step for MoEDAL called Cosmic MoEDAL, where we define a very large high altitude array to take the search for highly ionizing avatars of new physics to higher masses that are available from the cosmos. -

Chemistry: the Molecular Nature of Matter and Change

REVISED CONFIRMING PAGES The Components of Matter 2.1 Elements, Compounds, and 2.5 The Atomic Theory Today 2.8 Formula, Name, and Mass of Mixtures: An Atomic Overview Structure of the Atom a Compound 2.2 The Observations That Led to Atomic Number, Mass Number, and Binary Ionic Compounds an Atomic View of Matter Atomic Symbol Compounds That Contain Polyatomic Mass Conservation Isotopes Ions Definite Composition Atomic Masses of the Elements Acid Names from Anion Names Multiple Proportions 2.6 Elements: A First Look at the Binary Covalent Compounds The Simplest Organic Compounds: Dalton’s Atomic Theory Periodic Table 2.3 Straight-Chain Alkanes Postulates of the Atomic Theory Organization of the Periodic Table Masses from a Chemical Formula How the Atomic Theory Explains Classifying the Elements Representing Molecules with a the Mass Laws Compounds: An Introduction 2.7 Formula and a Model to Bonding 2.4 The Observations That Led to Mixtures: Classification and the Nuclear Atom Model The Formation of Ionic Compounds 2.9 Separation Discovery of the Electron and The Formation of Covalent An Overview of the Components of Its Properties Compounds Matter Discovery of the Atomic Nucleus (a) (b) (right) ©Rudy Umans/Shutterstock IN THIS CHAPTER . We examine the properties and composition of matter on the macroscopic and atomic scales. By the end of this chapter, you should be able to • Relate the three types of matter—elements or elementary substances, compounds, and mixtures—to the simple chemical entities that they comprise—atoms, ions, and molecules; -

Hypochlorous Acid Handling

Hypochlorous Acid Handling 1 Identification of Petitioned Substance 2 Chemical Names: Hypochlorous acid, CAS Numbers: 7790-92-3 3 hypochloric(I) acid, chloranol, 4 hydroxidochlorine 10 Other Codes: European Community 11 Number-22757, IUPAC-Hypochlorous acid 5 Other Name: Hydrogen hypochlorite, 6 Chlorine hydroxide List other codes: PubChem CID 24341 7 Trade Names: Bleach, Sodium hypochlorite, InChI Key: QWPPOHNGKGFGJK- 8 Calcium hypochlorite, Sterilox, hypochlorite, UHFFFAOYSA-N 9 NVC-10 UNII: 712K4CDC10 12 Summary of Petitioned Use 13 A petition has been received from a stakeholder requesting that hypochlorous acid (also referred 14 to as electrolyzed water (EW)) be added to the list of synthetic substances allowed for use in 15 organic production and handling (7 CFR §§ 205.600-606). Specifically, the petition concerns the 16 formation of hypochlorous acid at the anode of an electrolysis apparatus designed for its 17 production from a brine solution. This active ingredient is aqueous hypochlorous acid which acts 18 as an oxidizing agent. The petitioner plans use hypochlorous acid as a sanitizer and antimicrobial 19 agent for the production and handling of organic products. The petition also requests to resolve a 20 difference in interpretation of allowed substances for chlorine materials on the National List of 21 Allowed and Prohibited Substances that contain the active ingredient hypochlorous acid (NOP- 22 PM 14-3 Electrolyzed water). 23 The NOP has issued NOP 5026 “Guidance, the use of Chlorine Materials in Organic Production 24 and Handling.” This guidance document clarifies the use of chlorine materials in organic 25 production and handling to align the National List with the November, 1995 NOSB 26 recommendation on chlorine materials which read: 27 “Allowed for disinfecting and sanitizing food contact surfaces. -

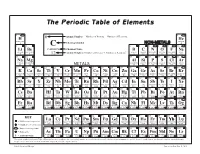

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

The Chemical Origin of Behavior Is Rooted in Abiogenesis

Life 2012, 2, 313-322; doi:10.3390/life2040313 OPEN ACCESS life ISSN 2075-1729 www.mdpi.com/journal/life Article The Chemical Origin of Behavior is Rooted in Abiogenesis Brian C. Larson, R. Paul Jensen and Niles Lehman * Department of Chemistry, Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, OR 97207, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (B.C.L.); [email protected] (R.P.J.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-503-725-8769. Received: 6 August 2012; in revised form: 29 September 2012 / Accepted: 2 November 2012 / Published: 7 November 2012 Abstract: We describe the initial realization of behavior in the biosphere, which we term behavioral chemistry. If molecules are complex enough to attain a stochastic element to their structural conformation in such as a way as to radically affect their function in a biological (evolvable) setting, then they have the capacity to behave. This circumstance is described here as behavioral chemistry, unique in its definition from the colloquial chemical behavior. This transition between chemical behavior and behavioral chemistry need be explicit when discussing the root cause of behavior, which itself lies squarely at the origins of life and is the foundation of choice. RNA polymers of sufficient length meet the criteria for behavioral chemistry and therefore are capable of making a choice. Keywords: behavior; chemistry; free will; RNA; origins of life 1. Introduction Behavior is an integral feature of life. Behavior is manifest when a choice is possible, and a living entity responds to its environment in one of multiple possible ways. -

TEK 8.5C: Periodic Table

Name: Teacher: Pd. Date: TEK 8.5C: Periodic Table TEK 8.5C: Interpret the arrangement of the Periodic Table, including groups and periods, to explain how properties are used to classify elements. Elements and the Periodic Table An element is a substance that cannot be separated into simpler substances by physical or chemical means. An element is already in its simplest form. The smallest piece of an element that still has the properties of that element is called an atom. An element is a pure substance, containing only one kind of atom. The Periodic Table of Elements is a list of all the elements that have been discovered and named, with each element listed in its own element square. Elements are represented on the Periodic Table by a one or two letter symbol, and its name, atomic number and atomic mass. The Periodic Table & Atomic Structure The elements are listed on the Periodic Table in atomic number order, starting at the upper left corner and then moving from the left to right and top to bottom, just as the words of a paragraph are read. The element’s atomic number is based on the number of protons in each atom of that element. In electrically neutral atoms, the atomic number also represents the number of electrons in each atom of that element. For example, the atomic number for neon (Ne) is 10, which means that each atom of neon has 10 protons and 10 electrons. Magnesium (Mg) has an atomic number of 12, which means it has 12 protons and 12 electrons. -

CHAPTER 12: the Atomic Nucleus

CHAPTER 12 The Atomic Nucleus ◼ 12.1 Discovery of the Neutron ◼ 12.2 Nuclear Properties ◼ 12.3 The Deuteron ◼ 12.4 Nuclear Forces ◼ 12.5 Nuclear Stability ◼ 12.6 Radioactive Decay ◼ 12.7 Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Decay ◼ 12.8 Radioactive Nuclides Structure of matter Dark matter and dark energy are the yin and yang of the cosmos. Dark matter produces an attractive force (gravity), while dark energy produces a repulsive force (antigravity). ... Astronomers know dark matter exists because visible matter doesn't have enough gravitational muster to hold galaxies together. Hierarchy of forces ◼ Sta Standard Model tries to unify the forces into one force Ernest Rutherford “Father of the Nucleus” Story so far: Unification Faraday Glashow,Weinberg,Salam Georgi,Glashow Green,Schwarz Witten 1831 1967 1974 1984 1995 Electricity } } } Electromagnetic force } } } Magnetism} } Electro-weak force } } } Weak nuclear force} } Grand unified force } } } 5 Different } Strong nuclear force} } D=10 String } M-theory ? } Theories } Gravitational force} +branes in D=11 Page 6 © Imperial College London Discovery of the Neutron 3) Nuclear magnetic moment: The magnetic moment of an electron is over 1000 times larger than that of a proton. The measured nuclear magnetic moments are on the same order of magnitude as the proton’s, so an electron is not a part of the nucleus. ◼ In 1930 the German physicists Bothe and Becker used a radioactive polonium source that emitted α particles. When these α particles bombarded beryllium, the radiation penetrated several centimeters of lead. The neutrons collide elastically with the protons of the paraffin thereby producing the5.7 MeV protons Discovery of the Neutron ◼ Photons are called gamma rays when they originate from the nucleus. -

Chapter 10 – Chemical Reactions Notes

Chapter 8 – Chemical Reactions Notes Chemical Reactions: Chemical reactions are processes in which the atoms of one or more substances are rearranged to form different chemical compounds. How to tell if a chemical reaction has occurred (recap): Temperature changes that can’t be accounted for. o Exothermic reactions give off energy (as in fire). o Endothermic reactions absorb energy (as in a cold pack). Spontaneous color change. o This happens when things rust, when they rot, and when they burn. Appearance of a solid when two liquids are mixed. o This solid is called a precipitate. Formation of a gas / bubbling, as when vinegar and baking soda are mixed. Overall, the most important thing to remember is that a chemical reaction produces a whole new chemical compound. Just changing the way that something looks (breaking, melting, dissolving, etc) isn’t enough to qualify something as a chemical reaction! Balancing Equations Notes: Things to keep in mind when looking at the recipes for chemical reactions: 1) The stuff before the arrow is referred to as the “reactants” or “reagents”, and the stuff after the arrow is called the “products.” 2) The number of atoms of each element is the same on both sides of the arrow. Even though there may be different numbers of molecules, the number of atoms of each element needs to remain the same to obey the law of conservation of mass. 3) The numbers in front of the formulas tell you how many molecules or moles of each chemical are involved in the reaction. 4) Equations are nothing more than chemical recipes. -

Cosmochemistry Cosmic Background Radia�On

6/10/13 Cosmochemistry Cosmic background radiaon Dust Anja C. Andersen Niels Bohr Instute University of Copenhagen hp://www.dark-cosmology.dk/~anja Hauser & Dwek 2001 Molecule formation on dust grains Multiwavelenght MW 1 6/10/13 Gas-phase element depleons in the Concept of dust depleon interstellar medium The depleon of an element X in the ISM is defined in terms of (a logarithm of) its reducon factor below the expected abundance relave to that of hydrogen if all of the atoms were in the gas phase, [Xgas/H] = log{N(X)/N(H)} − log(X/H) which is based on the assumpon that solar abundances (X/H)are good reference values that truly reflect the underlying total abundances. In this formula, N(X) is the column density of element X and N(H) represents the column density of hydrogen in both atomic and molecular form, i.e., N(HI) + 2N(H2). The missing atoms of element X are presumed to be locked up in solids within dust grains or large molecules that are difficult to idenfy spectroscopically, with fraconal amounts (again relave to H) given by [Xgas/H] (Xdust/H) = (X/H)(1 − 10 ). Jenkins 2009 Jenkins 2009 2 6/10/13 Jenkins 2009 Jenkins 2009 The Galacc Exncon Curve Extinction curves measure the difference in emitted and observed light. Traditionally measured by comparing two stars of the same spectral type. Galactic Extinction - empirically determined: -1 -1 <A(λ)/A(V)> = a(λ ) + b(λ )/RV (Cardelli et al. 1999) • Bump at 2175 Å (4.6 µm-1) • RV : Ratio of total to selective extinction in the V band • Mean value is RV = 3.1 (blue) • Low value: RV = 1.8 (green) (Udalski 2003) • High value: RV = 5.6-5.8 (red) (Cardelli et al. -

Chemistry - B.S

Chemistry - B.S. College of (Biochemistry Option) Arts and Sciences The Department of Chemistry offers the Bachelor of Science degree for students who Graduation Composition and Communication Requirement intend to become professional chemists or do graduate work in chemistry or a closely (GCCR) related discipline. There are three options in the B.S. program: a traditional track WRD 310 Writing in the Natural Sciences ............................................................. 3 covering all the major areas of chemistry, an option that emphasizes biochemistry and an option in materials chemistry. The Biochemistry and Traditional Options are Graduation Composition and Communication certified by the American Chemical Society. A Bachelor of Arts degree program is Requirement hours (GCCR) .................................................................... 3 offered as well for students who want greater flexibility in the selection of courses to perhaps pursue more diverse degree options, including dual and double majors. For College Requirements all majors CHE 109 and CHE 110 have been defined as equivalent to CHE 105. The I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ................................... 0-14 Department also offers the Master of Science and the Doctor of Philosophy degree. II. Disciplinary Requirements a. Natural Science (completed by Major Requirements) 128 hours b. Social Science ......................................................................................... 3 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS)