CONTENTS Notes from the Chair and Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPS Newsletter October 2019.Pub

NPS Scotland OCTOBER 2019 NEWSLETTER AUTUMN ISSUE NPS SCOTLAND Inside this issue: BLAIR FINALS Chairman’s Report 2 In Hand Show 3 NPS Dressage 4 & 5 NPS Scotland Bake Off 6 & 7 Blair Finals Report & 8 & CHAMPIONS Championship Results 9 2019 Blair Photographs 10 – 12 Diary Dates 13 NPS Scotland 14 & 15 Committee Page 2 NPS Scotland WELCOME FROM OUR CHAIRMAN AND TO OUR AUTUMN 2019 NEWSLETTER Welcome to our third NPS Scotland newsletter for 2019 and with autumn as good as upon us, where has the year gone to – it just seems to have vanished before our eyes! Our Scottish Finals at Blair were once again a tremendous success and my thanks go to everyone who helps make this event happen. A full report will be given later in this newsletter and con- gratulations to all our newly crowned 2019 series champions and reserves. We do try to make Blair a day to remember for everyone and hope you enjoyed yourselves. Thanks got to all of our Young Judges who competed so successfully at the NPS Summer Cham- pionships in Malvern in August, and congratulation to Kayleigh Rose Evans for coming 2nd in the 18-25 year old section - a tremendous achievement. Congratulations also go to all our Scottish Members who competed so successfully at Malvern – some amazing placings and championships or reserves in many sections. Just great news. We still have two events to take place in 2019 and both follow on in quick succession. Firstly, we have our In Hand Show at Netherton, near Bridge of Earn, Perth on Saturday, 19th October. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Buy Your Next Home with Next Home Leading Perthshire Estate Agency

Buy your next home with Next Home Leading Perthshire Estate Agency 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, PH13 9HW £170,000 Many thanks for your interest in We offer free, no obligation mortgage 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, advice to all our buyers. PH13 9HW. Buying with If you have a property to sell contact us Next Home Estate Agents dedicate to arrange a valuation. We are known in themselves to be available when you are, getting our customers moving quicker and offering an unbeatable service 7 days a at a higher price than our competitors. Put Next Home week until 9pm. us to the test and get your free valuation today, call 01764 42 43 44. 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, We have the largest sales team in Perthshire, operating from our 5 offices If you would like to kept informed of other PH13 9HW throughout Perthshire and delivering more great properties like this one please sales than any other estate agent. register on our hot buyers list, where we will email you of new property listings and Not only are we Perthshire’s Number 1 property open days. choice but we are also local. One of the reasons we know the local markets so well is because we live here. So let us guide you through the selling and buying process. If you’re a first time buyer we have incentives to help get you onto the property ladder our consultants can advise you through the whole process. Next Home - 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, PH13 9HW 2 About the area Blairgowrie is a thriving town with the High Street being the focal point having a variety of local shops including a butcher, book shop, antique and local craft and gift shops together with well-known department stores and supermarkets. -

Coupar Angus Best Ever Cycling Festival

CANdo Coupar Angus and District Community Magazine ‘Eighth in the top ten healthiest places to live in the UK’ Coupar Angus best ever Cycling Festival ISSUE 90 July/August 2019 Joe Richards Collectables WANTED: Old tools & coins, Tilley lamps, war items 01828 628138 or 07840 794453 [email protected] Ryan Black, fish merchant in Coupar Bits n Bobs with Kids and Gifts Angus & area, Thursdays 8.30 am till 5 pm. At The Cross 12 till 12.45 ‘straight from the shore to your door’ CANdo July/August 2019 Editorial The other day I came across an interesting statistic, which you may have read in the local and national press. Apparently, Coupar Angus is one of the healthiest of places to live in the UK. It came eighth in a list of the top ten. You may view this with some scepticism - why not in the top three? Or with surprise that our town is mentioned at all. Further investigation revealed how the list was compiled. It comes from Liverpool University and the Consumer Data Research Centre. This body selected various criteria and applied them to towns and villages across the country. These criteria included access to health services - mainly GPs and dentists - air/environmental quality, green spaces, amenities and leisure facilities. With its Butterybank community woodland, park and blue spaces like the Burn, Coupar Angus did well in this analysis. If you are fit and healthy you may be gratified by this result. If however you are less fortunate, this particular league table will have less appeal. But it is salutary to learn that your home town has many advantages. -

GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE and STEADINGS Kettins • Blairgowrie • Perthshire • PH13 9HA

GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE AND STEADINGS Kettins • Blairgowrie • Perthshire • Ph13 9HA GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE AND STEADINGS Kettins • Blairgowrie • Perthshire • Ph13 9HA A traditional farmhouse with substantial stone steadings and paddocks For sale as a whole or in 3 lots Perth 14 miles, Dundee 14 miles, Blairgowrie 6 miles, Coupar Angus 3 miles (all distances are approximate) LOT 1 – GREENBURNS FARMHOUSE 3-4 reception rooms • 3 bedrooms • Enclosed garden and paddock Stone cart shed, kennel and fuel store About 0.89 acres EPC Rating = E LOT 2 – NORTHERN STEADING AND PADDOCK Traditional stone barns (approx 441 sqm / 4748 sqft) Steel framed hay barn • Paddock About 0.72 acres LOT 3 – EASTERN STEADING AND PADDOCK Traditional stone byres and stores (approx. 943 sqm / 10149 sqft) About 0.74 acres In all about 2.35 acres Savills Perth Solicitors Earn House, Broxden Business Park Murray Beith Murray Lamberkine Drive, Perth PH1 1RA 1-3 Glenfinlas Street [email protected] EH3 6AQ Tel: 01738 445588 Tel: 0131 225 1200 VIEWING Strictly by appointment with Savills – 01738 477525. DIRECTIONS From Coupar Angus take the Dundee road (A923) heading south. After about 0.6 miles turn left towards Ardler. The entrance to Greenburns Farm is on the left hand side after about half a mile. SITUATION Greenburns Farmhouse is surrounded by some of Perthshire’s most fertile farmland and has lovely open views across the countryside. While offering a peaceful rural lifestyle, it is only about 1 mile from Kettins village, 3 miles from the centre of Coupar Angus and about 14 miles from both Perth and Dundee. Kettins has a popular primary school and village amenities include a football pitch. -

Bridge of Earn Community Council

Earn Community Conversation – Final Report 1.1 Bridge of Earn Community Council - Community Conversation January 2020 Prepared by: Sandra Macaskill, CaskieCo T 07986 163002 E [email protected] 1 Earn Community Conversation – Final Report 1.1 Executive Summary – Key Priorities and Possible Actions The table below summaries the key actions which people would like to see as a result of the first Earn Community Conversation. Lead players and possible actions have also been suggested but are purely at the discretion of Earn Community Council. Action Lead players First steps/ Quick wins A new doctor’s surgery/ healthcare facility • Community • Bring key players together to plan an innovative for Bridge of Earn e.g. minor ailments, • NHS fit for the future GP and health care provision district nurse for Bridge of Earn • Involve the community in designing and possibly delivering the solution Sharing news and information – • Community Council • seeking funding to provide a local bi-monthly Quick • Newsletter in paper form • community newsletter Win • Notice boards at Wicks of Baigle • develop a Community Council or community Rd website where people can get information and • Ways of creating inclusive possibly have a two-way dialogue (continue conversations conversation) • enable further consultation on specific topics No public toilet facilities in Main Street • local businesses • Is there a comfort scheme in operation which Bridge of Earn • PKC could be extended? Public Transport • Community • Consult local people on most needed routes Bus services -

Gifts and Deposits, 1549-2003 MS14/2 Lampoon of Kaiser Wilhelm, C1918

Perth & Kinross Council Archive Collections Politics and the State MS14 Miscellaneous gifts and deposits, 1549-2003 MS14/2 Lampoon of Kaiser Wilhelm, c1918 MS14/7 Perth Ward Associations: Minute book, 1945-1951 (Sixth Ward), 1951-1975 (Eighth Ward); Members card with rules, nd MS14/16 Thomas Murie, Perthshire Militia papers [copies, nd], 1798- 1801;1950 MS14/20 Extracts [nd] from the minute book of the Carse of Gowrie Turnpike Trust, 1827-1828 MS14/23 The Law Society of Scotland: Solicitors (Scotland) Act, 1949. Election of council of the society bye-election, Fife and Kinross constituency, 1951 MS14/30 Copy [nd] of the ‘Rolls of the Bishops, Nobilitie, Officers of State, Commissioners for Shires and Burghs of ye Kingdom of Scotland, called in parliament at Edinburgh 28 July 1681. By his Royal Highnesse James Duke of Albanie and York, His Majesties High Commissioner &c’, 1681 MS14/31 Letter from W Ramsay, minister, Alyth to John McNicoll, Edinburgh, discusses arrangements for the county election, 1833 MS14/42 Commission of captaincy in the Perthshire militia, granted by the Earl of Kinnoull to Fletcher Norton Menzies, 1846 Page 1 of 8 Perth & Kinross Council Archive Collections Politics and the State MS14/69 Copy [nd] summons from Oliver Cromwell to Praise God Barebone to appear at the Council Chamber in Whitehall on 4 July 1653 as Member of Parliament for the City of London,1653 MS14/84 Military discharge in favour of Henry Hubert, a Swiss who served as a quarter master sergeant in the Elgin Fencibles, 1797 MS14/99 Public notice of regulations -

PERTH & KINROSS Name Tel No. Fax No. Pharmacy Address1 Address2 Address3 Postcode 1 Donna Mcsween 01738

COMMUNITY PHARMACY - PERTH & KINROSS Name Tel no. Fax no. Pharmacy Address1 Address2 Address3 Postcode 1Donna McSween 01738 494610 01738 494611 Asda Pharmacy Asda Superstore 89 Dunkeld Road PERTH PH1 5AP Caroline Rattray 01738 494610 01738 494611 Asda Pharmacy Asda Superstore 89 Dunkeld Road PERTH PH1 5AP Ian Duncan 01738 494610 01738 494611 Asda Pharmacy Asda Superstore 89 Dunkeld Road PERTH PH1 5AP 2 Elaine Murphy 01738 623837 01738 447698 Blair, R P Chemist 44 South Methven Street PERTH PH1 5NU 3 Carol Lewis- Manager (P/T) 01764 652310 01764 653665 Boots the Chemist Ltd 9/11 High Street CRIEFF PH7 3HU Nicola McInally 01764 652310 01764 653665 Boots the Chemist Ltd 9/11 High Street CRIEFF PH7 3HU 4 Gillian Stephen 01738 629181 01738 625949 Boots the Chemist Ltd 145/159 High Street PERTH PH1 5UN Jill Buchan 01738 629181 01738 625949 Neil Campbell (PT) 01738 629181 01738 625949 5 Susan McCaffrey 01250 872029 01250 874704 Boots the Chemist Ltd 49 Allan Street BLAIRGOWRIE PH10 6AB 6 Gordon Brown 01738 443667 01738 443667 Browns Pharmacy Healthcare 196 High Street PERTH PH1 5PA 7Mark Napier 01738 624843 01738 624843 Browns Pharmacy Healthcare 21 North Methven Street PERTH PH1 5PN 8 Brian Timlin 01821 641211 01821 641212 Carse Chemist High Street ERROL PH2 7QJ 9Alison Henry 01764 670210 01764 670210 Comrie Dispensary Ltd Drummond Street COMRIE PH6 2DS Lorraine Brock 01764 670210 Comrie Dispensary Ltd Drummond Street COMRIE PH6 2DS 10 Mark Jenkins 01887 820324 01887 820324 Davidsons Chemists 7 Bank Street ABERFELDY PH15 2BB 11 Georgina Walker -

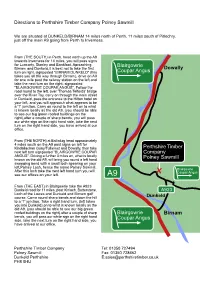

PDF Map and Directions

Directions to Perthshire Timber Company Polney Sawmill We are situated at DUNKELD/BIRNAM 14 miles north of Perth, 11 miles south of Pitlochry, just off the main A9 going from Perth to Inverness. From (THE SOUTH) in Perth, head north up the A9 towards Inverness for 14 miles, you will pass signs for Luncarty, Stanley and Bankfoot. Aproaching Blairgowrie Birnam and Dunkeld,it is best not to take the first turn on right, signposted "BIRNAM DUNKELD" (this Coupar Angus takes you all the way through Birnam), drive on A9 for one mile past the railway station on the left and take the next turn on the right, signposted "BLAIRGOWRIE COUPAR ANGUS". Follow the road round to the left, over 'Thomas Telfords' bridge over the River Tay, carry on through the main street in Dunkeld, pass the entrance to the Hilton hotel on your left, and you will approach what appears to be a 'T' junction. Carry on round to the left on to what is known locally as the old A9, (you should be able to see our big green roofed buildings on the right),after a couple of sharp bends, you will pass our white sign on the right hand side, take the next turn on the right hand side, you have arrived at our office. From (THE NORTH) at Ballinluig head approximately 4 miles south on the A9 past signs on left for Kindallachan Guay/Tulliemet and Dowally, then take Perthshire Timber next left turn signposted "BLAIRGOWRIE COUPAR Company ANGUS". Driving a further 3 miles on, what is locally Polney Sawmill known as the old A9, will bring you round a left hand sweeping bend with a small loch apearing on your left,Polney Loch, hence the name Polney Sawmill. -

Post Office Perth Directory

3- -6 3* ^ 3- ^<<;i'-X;"v>P ^ 3- - « ^ ^ 3- ^ ^ 3- ^ 3* -6 3* ^ I PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION 1 3- -e 3- -i 3- including I 3* ^ I KINROSS-SHIRE | 3» ^ 3- ^ I These books form part of a local collection | 3. permanently available in the Perthshire % 3' Room. They are not available for home ^ 3* •6 3* reading. In some cases extra copies are •& f available in the lending stock of the •& 3* •& I Perth and Kinross District Libraries. | 3- •* 3- ^ 3^ •* 3- -g Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeperthd1878prin THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 1878 AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH ^ Jleto ^lan of the Citg ant) i^nbixons, ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR THE WORK. PERTH: PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY LEITCH & LESLIE. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS. I §ooksz\ltmrW'Xmm-MBy & Stationers, | ^D, SILVER, COLOUR, & HERALDIC STAMPERS, Ko. 23 Qeorqe $treet, Pepjh. An extensive Stock of BOOKS IN GENERAL LITERATURE ALWAYS KEPT IN STOCK, THE LIBRARY receives special attention, and. the Works of interest in History, Religion, Travels, Biography, and Fiction, are freely circulated. STATIONEEY of the best Englisli Mannfactura.. "We would direct particular notice to the ENGRAVING, DIE -SINKING, &c., Which are carried on within the Previises. A Large and Choice Selection of BKITISK and FOEEIGU TAEOT GOODS always on hand. gesigns 0f JEonogntm^, Ac, free nf rhitrge. ENGLISH AND FOREIGN NE^A^SPAPERS AND MAGAZINES SUPPLIED REGULARLY TO ORDER. 23 GEORGE STREET, PERTH. ... ... CONTENTS. Pag-e 1. -

Tilley Awards 2003

Tilley Awards 2003 Project Title Thrillseekers Club. Category Operational support in police forces. Name of Police Force Tayside Police Force. Endorsing Chief Officer Mr Willie Bald, Assistant Chief Constable (Operations), Tayside Police. Contact Details - Name: Fergus Storrier Position : Sergeant Address : Community Safety, Western Division Headquarters, Perth Police Office, Barrack Street, Perth, PHI 5SF. Telephone number : 01738 892644 Email address: [email protected] THRILLSEEKERS CLUB SUMMARY The Thrillseekers Club is based in the town of Blairgowrie within Perth and Kinross. The project aims to work in partnership with voluntary, statutory, and private sector partners to provide positive alternatives for young people aged from 12 to 18 years of age (secondary school pupils) within the area. Blairgowrie, with a population of some 12000 people is situated within a rural area with the major cities of Perth and Dundee, being some 16 miles away. The area also has a number of outlying villages including Alyth and Coupar Angus. The area itself is very indicative of most rural settings with very little facilities for young people, difficulties with transport networks, and occasional tensions between the younger and older generations. Youth calls within the area were a particular issue, with Friday nights being highlighted as a peak time. The calls included alcohol-related annoyance, vandalism, and anti-social behaviour. Recent research within the Perth and Kinross area (2002 - Schools survey) around drug and alcohol use amongst under 16's has also shown a higher than national average (Scotland) of illicit drug use and alcohol consumption amongst school pupils in the area. A large part of the problem had been attributed towards a lack of credible, accessible, and affordable alternatives within rural areas, and the fact that younger and older teenagers often mix together within smaller villages so allowing for greater access to 'risk taking' practises for younger children. -

Glenview Auchterarder • Perthshire

Glenview AUCHTeRARDeR • PeRTHSHiRe Glenview ORCHil ROAD • AUCHTeRARDeR • PeRTHSHiRe • PH3 1nB A SUPeRB COnTemPORARy fAmily HOme wiTH STUnninG viewS TOwARDS THe OCHil HillS BeyOnD Kitchen / breakfast room, sitting room, sun room, dining area, utility room, WC. Galleried landing, family area, 4 Bedrooms (all en suite), south facing balcony. Double garage, parking area, Front and rear gardens. About 0.44 Acres EPC= B Wemyss House 8 Wemyss Place Edinburgh EH3 6DH 0131 247 3738 [email protected] SiTUATiOn Glenview sits in a superb setting close to the heart of Auchterarder and the world famous Gleneagles Hotel, with excellent south facing views over Auchterarder Golf Course and towards the Ochil Hills in the distance. Gleneagles Hotel offers a wealth of facilities including three championship courses, The Kings, The Queens and the PGA Centenary, which was the course venue for the 2014 Ryder Cup. Auchterarder provides good day to day services. Nearby Gleneagles railway station provides daily services north and south, including a sleeper service to London, while Dunblane provides commuter services to both Edinburgh and Glasgow. Perth lies some 15 miles to the east and offers a broad range of national retailers, theatre, concert hall, cinema, restaurants and railway station. The cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow can be reached in about an hour's journey by car, and provide international airports, railway stations and extensive city amenities. Independent schools in Perthshire include Morrison's Academy and Ardvreck in Crieff, Glenalmond just beyond; Craigclowan on the edge of Perth and Kilgraston and Strathallan near Bridge of Earn. Dollar Academy is also within easy reach.