Mini Trail Place Names of the Cateran Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Deer Management Plan for Sub Area 1 of the East Grampians DMG 2016-2021

Deer Consultancy Services A Deer Management Plan for Sub Area 1 of the East Grampians DMG 2016-2021 Colin McClean [email protected] 07736 722180 Laura Taylor [email protected] 07966 201859 East Grampian SA1 Deer Management Plan 2016-2021 Contents Executive Summary 5 Summary of Actions Arising from East Grampian Sub Group 1 Deer Management Plan 6 1. Introduction 10 1.1 Purpose of Plan 10 1.2 Management Structures and Agreements which influence deer management 10 within SA1 1.3 A new name for SA1? 12 1.4 Boundary 13 1.5 Membership 13 1.6 The Member Estates 14 1.6.1 Airlie West (Tarrabuckle) 14 1.6.2 Alrick 14 1.6.3 Auchavan 14 1.6.4 Auldallan 14 1.6.5 Balintore 14 1.6.6 Clova South 14 1.6.7 Corrie Fee 15 1.6.8 FCS Glenisla/ Glenmarkie and Glen Prosen 15 1.6.9 Glen Cally 15 1.6.10 Glenhead/Glen Damph (Scottish Water) 15 1.6.11 Glen Isla 16 1.6.12 Glen Prosen and Balnaboth 16 1.6.13 Glen Shee 17 1.6.14 Harran Plantation 17 1.6.15 Lednathie 17 1.6.16 Pearsie 17 1.6.17 Tulchan 18 1.7 Summary of Member’s Objectives 18 2. Deer Management Group: Organisation, Function & Policies 18 Deer Consultancy Services 2016 2 East Grampian SA1 Deer Management Plan 2016-2021 2.1 Updating the Constitution 18 2.2 Code of Practice on Deer Management 19 2.3 ADMG Principles of Collaboration 19 2.4 Best Practice Guidance 19 2.5 Long Term Vision 19 2.6 Strategic Objectives 19 2.7 Communications Policy 20 2.8 Authorisations 20 2.9 Training Policy 21 2.10 Deer Counting Policy 21 2.11 Counting in Woodland 22 2.12 Mortality Searches 22 2.13 Recruitment Counts 23 2.14 Venison Marketing 24 2.15 Strategic Fencing 24 3. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors Who’s Who Guide 2017-2022 Key to Phone Numbers: (C) - Council • (M) - Mobile Alasdair Bailey Lewis Simpson Labour Liberal Democrat Provost Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Dennis Melloy Conservative Tel 01738 475013 (C) • 07557 813291 (M) Tel 01738 475093 (C) • 07909 884516 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 2 Strathmore Angus Forbes Colin Stewart Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Tel 01738 475034 (C) • 07786 674776 (M) Email [email protected] Tel 01738 475087 (C) • 07557 811341 (M) Tel 01738 475064 (C) • 07557 811337 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Provost Depute Beth Pover Bob Brawn Kathleen Baird SNP Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 3 Carse of Gowrie Blairgowrie & Ward 9 Glens Almond & Earn Tel 01738 475036 (C) • 07557 813405 (M) Tel 01738 475088 (C) • 07557 815541 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Fiona Sarwar Tom McEwan Tel 01738 475086 (C) • 07584 206839 (M) SNP SNP Email [email protected] Ward 2 Ward 3 Strathmore Blairgowrie & Leader of the Council Glens Tel 01738 475020 (C) • 07557 815543 (M) Tel 01738 475041 (C) • 07984 620264 (M) Murray Lyle Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Conservative Caroline Shiers Ward 7 Conservative Strathallan Ward 3 Ward Map Blairgowrie & Glens Tel 01738 475037 (C) • 07557 814916 (M) Tel 01738 475094 (C) • 01738 553990 (W) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 11 Perth City North Ward 12 Ward 4 Perth City Highland -

Buy Your Next Home with Next Home Leading Perthshire Estate Agency

Buy your next home with Next Home Leading Perthshire Estate Agency 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, PH13 9HW £170,000 Many thanks for your interest in We offer free, no obligation mortgage 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, advice to all our buyers. PH13 9HW. Buying with If you have a property to sell contact us Next Home Estate Agents dedicate to arrange a valuation. We are known in themselves to be available when you are, getting our customers moving quicker and offering an unbeatable service 7 days a at a higher price than our competitors. Put Next Home week until 9pm. us to the test and get your free valuation today, call 01764 42 43 44. 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, We have the largest sales team in Perthshire, operating from our 5 offices If you would like to kept informed of other PH13 9HW throughout Perthshire and delivering more great properties like this one please sales than any other estate agent. register on our hot buyers list, where we will email you of new property listings and Not only are we Perthshire’s Number 1 property open days. choice but we are also local. One of the reasons we know the local markets so well is because we live here. So let us guide you through the selling and buying process. If you’re a first time buyer we have incentives to help get you onto the property ladder our consultants can advise you through the whole process. Next Home - 2 Monks Way, Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, PH13 9HW 2 About the area Blairgowrie is a thriving town with the High Street being the focal point having a variety of local shops including a butcher, book shop, antique and local craft and gift shops together with well-known department stores and supermarkets. -

Coupar Angus Best Ever Cycling Festival

CANdo Coupar Angus and District Community Magazine ‘Eighth in the top ten healthiest places to live in the UK’ Coupar Angus best ever Cycling Festival ISSUE 90 July/August 2019 Joe Richards Collectables WANTED: Old tools & coins, Tilley lamps, war items 01828 628138 or 07840 794453 [email protected] Ryan Black, fish merchant in Coupar Bits n Bobs with Kids and Gifts Angus & area, Thursdays 8.30 am till 5 pm. At The Cross 12 till 12.45 ‘straight from the shore to your door’ CANdo July/August 2019 Editorial The other day I came across an interesting statistic, which you may have read in the local and national press. Apparently, Coupar Angus is one of the healthiest of places to live in the UK. It came eighth in a list of the top ten. You may view this with some scepticism - why not in the top three? Or with surprise that our town is mentioned at all. Further investigation revealed how the list was compiled. It comes from Liverpool University and the Consumer Data Research Centre. This body selected various criteria and applied them to towns and villages across the country. These criteria included access to health services - mainly GPs and dentists - air/environmental quality, green spaces, amenities and leisure facilities. With its Butterybank community woodland, park and blue spaces like the Burn, Coupar Angus did well in this analysis. If you are fit and healthy you may be gratified by this result. If however you are less fortunate, this particular league table will have less appeal. But it is salutary to learn that your home town has many advantages. -

The Military Road from Braemar to the Spittal Of

E MILITARTH Y ROAD FROM BRAEMA E SPITTATH O RT L OF GLEN SHEE by ANGUS GRAHAM, F.S.A.SCOT. THAT the highway from Blairgowrie to Braemar (A 93) follows the line of an old military roa mattea s di commof o r n knowledge, thoug wore hth ofteks i n attributed, wrongly, to Wade; but its remains do not seem to have been studied in detail on FIG. i. The route from Braemar to the Spittal of Glen Shee. Highway A 93 is shown as an interrupted line, and ground above the ajoo-foot contour is dotted the ground, while published notes on it are meagre and difficult to find.1 The present paper is accordingly designed to fill out the story of the sixteen miles between BraemaSpittae th Glef d o l an rn Shee (fig. i). Glen Cluni Gled ean n Beag, wit Cairnwele hth l Pass between them,2 havo en outlinn a histors r it f Fraser1e eFo o yse Ol. e M.G ,d Th , Deeside Road (1921) ff9 . 20 , O.Se Se 2. Aberdeenshiref 6-inco p hma , and edn. (1901), sheets xcvm, cvi, cxi, surveye 186n di d 6an revised in 1900; ditto Perthshire, 2nd edn. (1901), sheets vin SW., xiv SE., xv SW., xv NW. and NE., xxm NE., surveye 186n di revised 2an 1898n deditioi e Th . Nationan no l Grid line t (1964s ye doe t )sno include this area, and six-figure references are consequently taken from the O.S. 1-inch map, yth series, sheet 41 (Braemar)loo-kmn i e ar l . -

An Original Collection of the Poems of Ossian, Orrann, Ulin, and Other

mmt^ \ .30 ^41(^^4^^ I. ol OC'V'tuO fviM^ IaaJI'^S /mu.O^civ- ItcchecUCui, C^'V^ci^uu ^/Ilo ^i^^u/ 4W<; Wt ^t^C^ Jf^ [W^JLWtKA c^ Cjn^uCiJi tri/xf)^ Ciyi>^^ CA^(A^ ^^" l^/Ji^^^JL. Irk. /UuJL . TWw- c/?Z^ ?iJI7 A-^c*^ yi^lU. ^'^ C/iiuyu^ G^AMA^f\M^ yJ\f\MMA/^ InJieuti J^tT^Tl^JU^ C)nc(A\.p%2=k ^^^^^^^ A^^^ /^^^^^ yi^ UvyUSi^ ,at ["hoy, Ci/^yul Qcc/iA^i'ey. ftul^k hJiruo^/iil!;^ AH ORIGINAL COLLECTION OF THB POEMS OF OSSIAN, OMIRANN, IJJLIN, WHO FLOURISHED ZN THE SAME AGE. COLLECTEB ANO EDITED BY HUGH AND JOHN M'CALLUM. MONTROSE: PrfiiteD at t^e ISeiJieto Behjjspapet; <£^cc, FOR THE EDITORS, By James Watt, Bookaeller. I8iej. DEDICATED (bY PERMISSION), TO THE JDUKE OF YORK, PRESIDENT, AND THE OTHER NOBLE AND ILLUSTRIOUS MEMBERS OF THE HIGHLAND SOCIETY OP PREFACE. After the Editors devoted much of their time in compiling materials for an additional collec- tion of Ossian's poems, and in comparing different editions collected from oral recitation; having also perused the controversy, ^vritten by men of highly respectable abilities, establisliing the au- thenticity of the poems of Ossian ; also, upon the other hand, considered what has been stated a- gainst the authenticity of these poems, by a few whose abilities are well known in other matters, though they have failed in this vain and frivolous attempt. Having contemplated both sides of the question, and weighed the balance with reason and justice; the Editors consulted with some of the first characters in the nation about the matter, who, after serious consideration, have granted their approbation for publishing the following sheets, and favoured the Editors, not only with vi PREFACE. -

The Scottish Society of Indianapolis from the Desk of the President

The Scottish Society of Indianapolis Fall Edition, September - November 2015 2015 Board of Trustees Robin Jarrett, President, [email protected] Steven Johnson, Treasurer [email protected] From the desk of the President Elisabeth Hedges, Secretary Fellow Scots, [email protected] The Society is having a great year. We have been preparing for the upcoming festival season in which we will make many appearances. You may already know Carson C Smith, Trustee that the practice of setting up a Society booth is how we perpetuate our charter, [email protected] educating the public in “Gach ni Albanach” (all things Scottish). It also helps the public become aware that there is a Scottish Community and people of Scottish Andy Thompson, Trustee descent living in the Indianapolis and metro areas. This often surprises people when [email protected] they hear it. It is a special experience to point out to visitors that their last name is indeed Scottish, to show their name in the COSCA book and help them find their tartan. Many of our ancestors moved to America so long ago, our heritage has been Samuel Lawson,Trustee forgotten. I’m sure over time we’ve inspired more than one person to pursue their [email protected] roots and to trace their own family’s path across the sea. Armand Hayes, Trustee Volunteering time in our Society booth is a great way to learn while you educate. [email protected] Members who haven’t manned the tent before can sign up for the same slots with others who have, and learn that it’s a rewarding and easy thing to do. -

Wildman Global Limited for Themselves and for the Vendor(S) Or Lessor(S) of This Property Whose Agents They Are, Give Notice That: 1

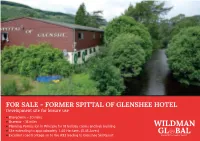

FOR SALE - FORMER SPITTAL OF GLENSHEE HOTEL Development site for leisure use ◆ Blairgowrie – 20 miles ◆ Braemar – 15 miles ◆ Planning Permission in Principle for 18 holiday cabins and hub building WILDMAN ◆ Site extending to approximately 1.40 Hectares (3.45 Acres) GL BAL ◆ Excellent road frontage on to the A93 leading to Glenshee Ski Resort PROPERTY CONSULTANT S LOCATION ACCOMMODATION VIEWING The Spittal of Glenshee lies at the head of Glenshee in the The subjects extend to an approximate area of 1.40 Hectares Strictly by appointment with the sole selling agents. highlands of eastern Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The village has (3.45 Acres). The site plan below illustrates the approximate become a centre for travel, tourism and winter sports in the region. site boundary. SITE CLEARANCE The subjects are directly located off the A93 Trunk Road which The remaining buildings and debris will be removed from the site by leads from Blairgowrie north past the Spittal to the Glenshee Ski PLANNING the date of entry. Centre and on to Braemar. The subjects are sold with the benefit of Planning Permission in Principle (PPiP) from Perth & Kinross Council to develop the entire SERVICES The village also provides a stopping place on the Cateran Trail site to provide 18 holiday cabins, a hub building and associated car ◆ Mains electricity waymarked long distance footpath which provides a 64-mile (103 parking. ◆ Mains water km) circuit in the glens of Perthshire and Angus. ◆ Further information with regard to the planning consent is available Private drainage DESCRIPTION to view on the Perth & Kinross website. -

Notices and Proceedings

THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER FOR THE SCOTTISH TRAFFIC AREA NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2005 PUBLICATION DATE: 15 April 2013 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 06 May 2013 Correspondence should be addressed to: Scottish Traffic Area Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/04/2013 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to bus registrations and public inquiries should be sent to: Scottish Traffic Area Level 6 The Stamp Office 10 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG The public counter in Edinburgh is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. Please note that only payments for bus registration applications can be made at this counter. The telephone number for bus registration enquiries is 0131 200 4927. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region. -

Cateran Trail Is a Fully-Waymarked, 64-Mile (103 Km) Route Through Perthshire and the Angus Glens — the Heart of Scotland

EXPLORE THIS FULLY- CATERAN TRAIL MAPS WAYMARKED, 64-MILE The map inside this leaflet is solely an illustration of the (103 km) CIRCULAR ROUTE Cateran Trail. THROUGH THE HEART OF To walk the Trail, all visitors should bring a detailed map and compass for navigation. We recommend SCOTLAND, APPROXIMATELY the specially-created, waterproof, 1:40,000 Footprint 1 ½ HOURS NORTH OF map published by Stirling Surveys or the Cateran Trail EDINBURGH. Guidebook published by Rucksack Readers, which contains both the Footprint map and detailed, up-to- date descriptions of each section of the Trail. www.stirlingsurveys.co.uk/nationaltrails.html GEOCACHING ON THE CATERAN TRAIL www.rucsacs.com/books/Cateran-Trail Perthshire is the geocaching capital of Scotland, and The Cateran Trail is home to a special GeoTrail with collectable bronze and antique silver geocoins to be won. www.caterantrail.org/geocaching CATERAN TRAIL APP There is a free app available to download from the Google Play Store that brings the Trail to life with folklore, insights and stories about the area, including the Glenisla giants, the Herdsman of Alyth and the legend of Queen Guinivere. The Cateran Trail follows old drove roads and ancient tracks across a varied terrain of farmland, forests and moors. Some of these routes follow the same ones used by the Caterans – fearsome cattle thieves who raided Strathardle, Glenshee and Glen Isla from the Middle Ages to the 17th century and for whom the Trail is named. The Cateran Trail is managed and maintained by Perth & Kinross Countryside Trust with the kind permission The map inside this leaflet shows details of the five and co-operation of the stages of the Trail and the mini trail.