Shared Power Under the Constitution: the Independent Counsel Joseph R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates Over Urban Public Space

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates over Urban Public Space Anna Rascovar The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2019 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] WASHINGTON SQUARE PARK: STRUGGLES AND DEBATES OVER URBAN PUBLIC SPACE by ANNA RASCOVAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 ANNA RASCOVAR All Rights Reserved ii Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates over Urban Public Space by Anna Rascovar This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date David Humphries Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates over Urban Public Space by Anna Rascovar Advisor: David Humphries Public space is often perceived as a space that is open to everyone and is meant for gatherings and interaction; however, there is often a great competition over the use and control of public places in contemporary cities. This master’s thesis uses as an example Washington Square Park, which has become a center of contention due to the interplay of public and private interests. -

An Original Model of the Independent Counsel Statute

Michigan Law Review Volume 97 Issue 3 1998 An Original Model of the Independent Counsel Statute Ken Gormley Duquesne University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, President/ Executive Department Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Ken Gormley, An Original Model of the Independent Counsel Statute, 97 MICH. L. REV. 601 (1998). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol97/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ORIGINAL MODEL OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL STATUTE Ken Gormley * TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 602 I. HISTORY OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL STATUTE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • . • • • • • • 608 A. An Urgent Push fo r Legislation . .. .. .. .. 609 B. Th e Constitutional Quandaries . .. .. .. .. 613 1. Th e App ointments Clause . .. .. .. .. 613 2. Th e Removal Controversy .. ................ 614 3. Th e Separation of Powers Bugaboo . .. 615 C. A New Start: Permanent Sp ecial Prosecutors and Other Prop osals .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 617 D. Legislation Is Born: S. 555 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 624 E. Th e Lessons of Legislative History . .. .. .. 626 II. THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS: ESTABLISHING THE LAW'S CONSTITUTIONALITY • . • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • • • . • • • 633 III. REFORMING THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL LAW • • . • 639 A. Refo rm the Method and Frequency of App ointing In dependent <;ounsels ..... :........ 641 1. Amend the Triggering Device . -

GOES BACK... SCHOOL Johnson Remain in Berlin

. N V Ploy FOUBTBEN PRTOAT, AUGUST IS, IW l iKani:t;i?0t>r lEofttitig l^eraUt AveraR:e Daily Net Press Run The Weather For the Ended FoMOMt ef U. 8. Weather • June 8, 1961 L. Thomas Burdick, 14 Xdgerton loney (V ): medley winner*. Day- St, is th Jerome, Idaho, attending Salter’s Winner son Wnibel, Art Petrone, Bill FOR RENT Fair, nets tsr t iswif r * *1 About Town the funeral of his mother, Mrs. Avery (S). 13,3.30 toalght. Lew M t* #4. Fair, There will be a ttl-pool meet be S and 16 mm. Movie Projectors Myrtle D. Burdick, who died last In Swim Event -HMund or silent, also SO mm. Member of the Audit Award* and c«rtlflcate* will b« night tween Globe, Salters and Ver- planck next Thursday evening at slid* projeetdrs. Bureea of Olrenlstloa preaentcd to children, wh^ attend The second swim meet between Manchester— A City of Village Charm ih* Salvation Army** Vacation VFVP Auxlllaiy and members contestants from Verplsnck and 6 at Salter's Pool. In addition to WELDON DRUG CO. Bible School, at closing exercises planning to go on the Mystery Ride the events mentioned above a free 901 Main 8 t TeL BO S-OStl Salter's Pools was h ^ last eve style will be added for nine and tonight at 7 at the church. A dls- Tuesday should make reservations ning with Salter's team winning by (ClaaeUIed Advertlalng on Page I) flay of pupils’ wortt will be shown, with Mrs. John Vince, 227 McKee ten year olds. -

30 Years of Progress 1934 - 1964

30 YEARS OF PROGRESS 1934 - 1964 DEPARTMENT OF PARKS NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR REPORT TO THE MAYOR AND THE BOARD OF ESTIMATE ROBERT F. WAGNER, Mayor ABRAHAM D. BEAME, Comptroller PAUL R. SCREVANE, President of the Council EDWARD R. DUDLEY. President. Borough of Manhattan JOSEPH F. PERICONI, President. Borough of The Bronx ABE STARK, President, Borough of Brooklyn MARIO J. CARIELLO, President, Borough of Queens ALBERT V. MANISCALCO, President, Borough of Richmond DEPARTMENT OF PARKS NEWBOLD MORRIS, Commissioner JOHN A. MULCAHY, Executive Officer ALEXANDER WIRIN, Assistant Executive Officer SAMUEL M. WHITE, Director of Maintenance & Operation PAUL DOMBROSKI, Chief Engineer HARRY BENDER, Engineer of Construction ALEXANDER VICTOR, Chief of Design LEWIS N. ANDERSON, JR., Liaison Officer CHARLES H. STARKE, Director of Recreation THOMAS F. BOYLE, Assistant Director of Maintenance & Operation JOHN MAZZARELLA, Borough Director, Manhattan JACK GOODMAN, Borough Director, Brooklyn ELIAS T. BRAGAW, Borough Director, Bronx HAROLD P. McMANUS, Borough Director, Queens HERBERT HARRIS, Borough Director. Richmond COVER: Top, Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Playground Left, New York 1664 Bottom, New York World's Fair 1964-1965 INDEX Page ARTERIALS Parkways and Expressways 57 BEACHES 36 BEAUTIFICATION OF PARKS 50 CONCESSIONS 51 ENGINEERING AND ARCHITECTURAL Design and Construction 41 GIFTS 12 GOLF 69 JAMAICA BAY Wildlife Refuge 8 LAND Reclamation and Landfill 7 MAINTENANCE and OPERATION 77 MARGINAL SEWAGE PROBLEM 80 MUSEUMS AND INSTITUTIONS 71 MONUMENTS 13 PARKS 10 RECREATION Neighborhood, Recreation Centers, Golden Age Centers, Tournaments, Children's Programs, Playgrounds, Special Activi- ties 15 SHEA STADIUM FLUSHING MEADOW 67 SWIMMING POOLS 40 WORLDS FAIR 1964-1965 Post-Fair Plans 56 ZOOS 76 SCALE MODEL OF NEW YORK CITY EXHIBITED IN THE CITY'S BUILDING AT WORLD'S FAIR. -

Proposals to Reform Special Counsel Investigations

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2021 Balancing Independence and Accountability: Proposals to Reform Special Counsel Investigations Lawrence Keating Fordham University School of Law Steven Still Fordham University School of Law Brittany Thomas Fordham University School of Law Samuel Wechsler Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence Keating, Steven Still, Brittany Thomas, and Samuel Wechsler, Balancing Independence and Accountability: Proposals to Reform Special Counsel Investigations, January (2021) Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/1111 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Balancing Independence and Accountability: Proposals to Reform Special Counsel Investigations Democracy and the Constitution Clinic Fordham University School of Law Lawrence Keating, Steven Still, Brittany Thomas, & Samuel Wechsler January 2021 Balancing Independence and Accountability: Proposals to Reform Special Counsel Investigations Democracy and the Constitution Clinic Fordham University School of Law Lawrence Keating, Steven Still, Brittany Thomas, & Samuel Wechsler January 2021 This report was researched and written during the 2019-2020 academic year by students in Fordham Law School’s Democracy and the Constitution Clinic, where students developed non-partisan recommendations to strengthen the nation’s institutions and its democracy. -

Download Full Book

Neighbors in Conflict Bayor, Ronald H. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Bayor, Ronald H. Neighbors in Conflict: The Irish, Germans, Jews, and Italians of New York City, 1929-1941. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.67077. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67077 [ Access provided at 27 Sep 2021 07:22 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Ronald H. Bayor Neighbors in Conflict The Irish, Germans, Jews, and Italians of New York City, 1929–1941 Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-2990-8 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-2990-X (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3062-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3062-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3102-4 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3102-5 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. NEIGHBORS IN CONFLICT THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY STUDIES IN HISTORICAL AND POLITICAL SCIENCE NINETY-SIXTH SEMES (1978) 1. -

Jonathan R. Bailyn

THE UNITED STATES and ISRAEL: CULTURAL FOUNDATIONS of the SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP JONATHAN R. BAILYN Submitted to the Department of Sociology and Anthropology ofAmherst College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors. Faculty Advisor: Jan Dizard 4 16 2007 Israel was not created in order to disappear - Israel will endure and flourish. It is the child of hope and home of the brave. It can neither be broken by adversity nor demoralized by success. It carries the shield of democracy and it honors the sword of freedom. -President John F. Kennedy the UNITED STATES and ISRAEL: CULTURAL FOUNDATIONS of the SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP __ INTRODUCTION: THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP 1 I. FOUNDATIONAL MYTHS 19 II. JEWISH ASSIMILATION 51 III. RELIGIOUS HERITAGE 81 IV. THE HOLOCAUST 103 V. STRATEGIC ALLIES 127 CONCLUSION: THE LIMITS 145 bibliography 163 __ Jonathan R. Bailyn INTRODUCTION: THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP THE LOBBY In March 2006, John J. Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago and Stephen M. Walt of Harvard University published The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy on Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government webpage. It was submitted as a digital “working paper” on March 13, 2006, and on March 23 was run in print by the London Review of Books.1 In the piece Mearsheimer and Walt contend that American foreign policy in the Middle East “is due almost entirely…to the activities of the ‘Israel Lobby.’”2 The Israel Lobby has managed to “skew” and “divert” U.S. foreign policy away from its own national interest while simultane- ously “convincing” America that U.S. -

Ridgefield Encyclopedia

A compendium of more than 3,300 people, places and things relating to Ridgefield, Connecticut. by Jack Sanders [Note: Abbreviations and sources are explained at the end of the document. This work is being constantly expanded and revised; this version was updated on 4-14-2020.] A A&P: The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened a small grocery store at 378 Main Street in 1948 (long after liquor store — q.v.); became a supermarket at 46 Danbury Road in 1962 (now Walgreens site); closed November 1981. [JFS] A&P Liquor Store: Opened at 133½ Main Street Sept. 12, 1935. [P9/12/1935] Aaron’s Court: short, dead-end road serving 9 of 10 lots at 45 acre subdivision on the east side of Ridgebury Road by Lewis and Barry Finch, father-son, who had in 1980 proposed a corporate park here; named for Aaron Turner (q.v.), circus owner, who was born nearby. [RN] A Better Chance (ABC) is Ridgefield chapter of a national organization that sponsors talented, motivated children from inner-cities to attend RHS; students live at 32 Fairview Avenue; program began 1987. A Birdseye View: Column in Ridgefield Press for many years, written by Duncan Smith (q.v.) Abbe family: Lived on West Lane and West Mountain, 1935-36: James E. Abbe, noted photographer of celebrities, his wife, Polly Shorrock Abbe, and their three children Patience, Richard and John; the children became national celebrities when their 1936 book, “Around the World in Eleven Years.” written mostly by Patience, 11, became a bestseller. [WWW] Abbot, Dr. -

Centurions in Public Service Preface 11 Acknowledgments Ment from the Beginning; Retired Dewey Ballantine Partner E

centurions in pu blic service Particularly as Presidents, Supreme Court Justices & Cabinet Members by frederic s. nathan centurions in pu blic service Particularly as Presidents, Supreme Court Justices & Cabinet Members by frederic s. nathan The Century Association Archives Foundation, New York “...devotion to the public good, unselfish service, [an d] never-ending consideration of human needs are in them - selves conquering forces. ” frankli n delano roosevelt Rochester, Minnesota, August 8, 1934 Table of Contents pag e 9 preface 12 acknowle dgments 15 chapte r 0ne: Presidents, Supreme Court Justices, and Cabinet Members 25 charts Showing Dates of Service and Century Association Membership 33 chapte r two: Winning World War II 81 chapte r three: Why So Many Centurions Entered High Federal Service Before 1982 111 chapte r four: Why Centurion Participation Stopped and How It Might Be Restarted 13 9 appendix 159 afterw0rd the century association was founded in 1847 by a group of artists, writers, and “amateurs of the arts” to cultivate the arts and letters in New York City. They defined its purpose as “promoting the advancement Preface of art and literature by establishing and maintaining a library, reading room and gallery of art, and by such other means as shall be expedient and proper for that purpose.” Ten years later the club moved into its pen ul - timate residence at 109 East 15 th Street, where it would reside until January 10, 1891 , when it celebrated its an - nual meeting at 7 West 43 rd Street for the first time. the century association archives founda - tion was founded in 1997 “to foster the Foundation’s archival collection of books, manuscripts, papers, and other material of historical importance; to make avail able such materials to interested members of the public; and to educate the public regarding its collec - tion and related materials.” To take these materials from near chaos and dreadful storage conditions to a state of proper conservation and housing, complete with an online finding aid, is an accomplishment of which we are justly proud. -

P a R T M E N Parks Arsenal, Central Park Regent 4-1000

DEPARTMEN O F P ARK S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4- I 00 0 FOR RELEAS^^E^ IMMEDIATELY l-l-l-60M-706844(61) ^^^ 114 NewboTd Morris, Commissioner of Parks, announces that the seven Christmas week Marionette performances of "Alice in Wonderland", scheduled to be held in the Hunter College Playhouse, have been over- subscribed and the public is hereby notified that no further requests for tickets can be honored. To date there have been over 15,000 requests for tickets for these free marionette performances with only 5,000 seats available for the four days. It is hoped that the many thousands of youngsters who have been denied the pleasure of seeing any of these performances, may see "Alice in Wonderland" during the winter showings at public and Paro- chial schools in the five boroughs. The travelling marionette theatre will be in the five boroughs according to the following schedule.. Until January S Manhattan Brooklyn Jan. 9 to Jan. 30 Bronx Jan. 31 to Feb. 20 Queens Feb. 26 to March 16 Richmond March 19 to March 27 •\ o /on DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE IMMEDIATELY l-l-l-60M-706844(61) «^»* 114 NewboTd Morris, Commissioner of Parks, announces that the seven Christmas week Marionette performances of "Alice in Wonderland", scheduled to be held in the Hunter College Playhouse, have been over- subscribed and the public is hereby notified that no further requests for tickets can be honored. To date there have been over 15,000 requests for tickets for these free marionette performances with only 5,000 seats available for the four days. -

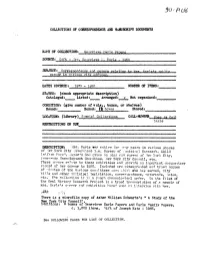

COLLECTIONS of CORRESPONDENCE and M/Knuscript DOCUMENTS

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND M/kNUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAJ*E OF COLLECTION: Genevieve Farle Papers SOURCES Gift - Mrs. Genevieve L. Farle - 1950 SUBJECT; Correspondence end papers relating to MT>S career in vnrious city offices. DATES COVERED: 19*5 - 1950 NUMBER OF ITEMSs STATUS! (check appropriate description) Cataloged; Listedi Arranged i x Not organized<^ CONDITION? (give number of vols#J boxes, or shelves) Bound : Boxed J t-8 boxes Stored s LOCATIONi (Library) Special Collections CALL-NUMBKR Spec ;/is Coll Earle RESTRICTIONS ON USE DESCRIPTION: Mrs. Earle was sctive for ;ieny years in various phases of levv York City poverrment i.e. Bureau of l.uniciosl Research, Child Velf?re Foar^, mayor's Co.n -iittee on plan end survey of "lev York City, K'nerfency Unemnloyinent Coauiittee, Ne^ York City Council, etc. These ospers relate to these activities end orovi.de an important documentary record of her career to 1S50. Included are mimeogr^ohed en^ typed copies of ninnt.es of the various committees upon which she has served," city bills and other municipal legislation, correspondence, memoranda, notes, etc. The collection is in a rouch chronolo^icel order. Tn the files of the Oral History Research Project is a. typed transcription of a memoir of Mrs. Earlefs csreer and activities fcssed uoon en interview y.-ith her. There is a microfilm copy of As her William Schwartz^ !l A Study of the New York City Council". Additions: 4 boxes of Genevieve Earle Papers and Earle family Papers, c. 1,000 items, Gift of Joseph Katz - 1965. See FOLLOWING PAGES FOR LIST OF COLLECTION. -

Special Investigations Involving U.S. Presidents and Their Admins Since 1973

Special Investigations Involving U.S. Presidents and Their Admins Since 1973 Second Update – August 13, 2019* Report Commissioned by the A-Mark Foundation www.amarkfoundation.org *Original Post – April 3, 2018 First update, April 16, 2019, and Second Update include updated Statement of Expenditures from Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller’s investigation. © 2019 A-Mark Foundation - This report is available for Fair Use. Special Investigations Involving U.S. Presidents Since 1973 Overview The A-Mark Foundation commissioned this report on special investigations involving presidents and those close to them following the appointment of Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller to investigate possible collusion among President Donald J. Trump, his presidential campaign and Russia in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. That investigation concluded on March 22, 2019. This report, with the exception of some commentary for historical context on the appointment of the first special prosecutor investigation,1 initiated by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1875, effectively begins with the Watergate investigation of President Richard M. Nixon in 1973. The report concludes with the end of the investigation into Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. Our criteria for the special investigations of the eight presidents [Barack H. Obama and his administration were not investigated] versus the investigations in the Appendix are as follows: The eight special investigations beginning in 1973 are investigations by special prosecutors/independent counsels/special counsels that began with possible offence(s) tied directly or indirectly to the president in office, and the investigation of President Gerald R. Ford which began with the investigation of President Nixon; the 22 special investigations in the Appendix are either prior to 1973, or when the investigations seemingly involved personal behavior or actions not tied directly or indirectly to administration business or action.