© 2015 Christopher Adam Mitchell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

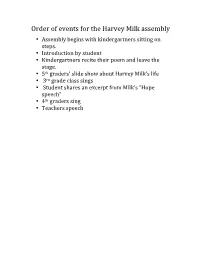

Order of Events for the Harvey Milk Assembly • Assembly Begins with Kindergartners Sitting on Steps

Order of events for the Harvey Milk assembly • Assembly begins with kindergartners sitting on steps. • Introduction by student • Kindergartners recite their poem and leave the stage. • 5th graders’ slide show about Harvey Milk’s life • 3rd grade class sings • Student shares an excerpt from Milk’s “Hope speech” • 4th graders sing • Teachers speech Student 1 Introduction Welcome students of (School Name). Today we will tell you about Harvey Milk, the first gay City Hall supervisor. He has changed many people’s lives that are gay or lesbian. People respect him because he stood up for gay and lesbian people. He is remembered for changing our country, and he is a hero to gay and lesbian people. Fifth Grade Class Slide Show When Harvey Milk was a little boy he loved to be the center of attention. Growing up, Harvey was a pretty normal boy, doing things that all boys do. Harvey was very popular in school and had many friends. However, he hid from everyone a very troubling secret. Harvey Milk was homosexual. Being gay wasn’t very easy back in those days. For an example, Harvey Milk and Joe Campbell had to keep a secret of their gay relationship for six years. Sadly, they broke up because of stress. But Harvey Milk was still looking for a spouse. Eventually, Harvey Milk met Scott Smith and fell in love. Harvey and Scott moved together to the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, which was a haven for people who were gay, a place where they were respected more easily. Harvey and Scott opened a store called Castro Camera and lived on the top floor. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

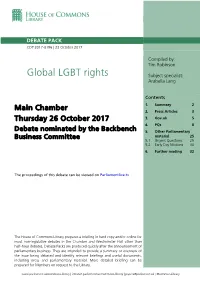

Global LGBT Rights Subject Specialist: Arabella Lang

DEBATE PACK CDP 2017-0196 | 23 October 2017 Compiled by: Tim Robinson Global LGBT rights Subject specialist: Arabella Lang Contents Main Chamber 1. Summary 2 2. Press Articles 3 Thursday 26 October 2017 3. Gov.uk 5 4. PQs 8 Debate nominated by the Backbench 5. Other Parliamentary Business Committee material 25 5.1 Urgent Questions 25 5.2 Early Day Motions 30 6. Further reading 32 The proceedings of this debate can be viewed on Parliamentlive.tv The House of Commons Library prepares a briefing in hard copy and/or online for most non-legislative debates in the Chamber and Westminster Hall other than half-hour debates. Debate Packs are produced quickly after the announcement of parliamentary business. They are intended to provide a summary or overview of the issue being debated and identify relevant briefings and useful documents, including press and parliamentary material. More detailed briefing can be prepared for Members on request to the Library. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Number 2017-0196, 20 October 2017 1. Summary Human rights of many LGBT people across the globe are being abused, for instance in Egypt, Azerbaijan and Chechnya. Arrests, imprisonment and mistreatment are common examples, and discrimination is even more widespread. LGBT rights are not fully protected in all the British Overseas Territories. Homosexual acts in private between consenting adults were decriminalised under the United Kingdom's Caribbean Territories (Criminal Law) Order 2000. This illustrates that in exceptional circumstances the UK is prepared to impose social reform on the Overseas Territories. -

The Caffe Cino

DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 31 Cornelia Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE No. 31 Cornelia Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. During those ten years, the coffee shop served as an experimental theater venue, becoming the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and New York City’s first gay theater. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 Former location of the Caffe Cino, 31 Cornelia Street 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman PHOTOGRAPHS BY LPC Staff Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 3 of 24 The Caffe Cino the National Parks Conservation Association, Village 31 Cornelia Street, Manhattan Preservation, Save Chelsea, and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, and 19 individuals. No one spoke in opposition to the proposed designation. The Commission also received 124 written submissions in favor of the proposed designation, including from Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz, New York Designation List 513 City Council Member Adrienne Adams, the LP-2635 Preservation League of New York State, and 121 individuals. -

Roditi, Edouard (1910-1992) by John Mcfarland

Roditi, Edouard (1910-1992) by John McFarland Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Poet, translator, literary and art critic, and short story writer, Edouard Roditi was associated with most of the twentieth-century's avant-garde literary movements from Surrealism to post-modernism. For more than sixty years, he produced such an astonishing variety of smart, lively, and moving poetry and prose that nobody objected when he dubbed himself "The Pharaoh of Eclecticism." A member of several predominantly homosexual social circles, Roditi maintained friendships with literary and artistic figures ranging from Paul Bowles and Jean Cocteau to Paul Tchelitchew and Christian Dior. His art and literary criticism held artists and writers to the very highest standards and insisted that intense but uncritical infatuation with flashy new trends could end in disappointment and heartbreak. His Internationalist Birthright Roditi was born in Paris on June 6, 1910. He was the beneficiary of a remarkably rich confluence of heritages--Jewish, German, Italian, French, Spanish, and Greek--and was truly international, both American and European. His father, Oscar, an Italian born in Constantinople, had become a United States citizen after his father emigrated to America and gained citizenship. Although Oscar's father had left the family behind in Europe, all the family in Europe became citizens when he did by virtue of the citizenship statutes in force at that time. Roditi's mother, Violet, had an equally rich family history. She was born in France but became an English citizen in her youth. When she married Oscar, she too became a United States citizen. -

The Diary, Photographs, and Letters of Samuel Baker Dunn, 1898-1899

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Spring 2016 Achieving Sourdough Status: The Diary, Photographs, and Letters of Samuel Baker Dunn, 1898-1899 Robert Nicholas Melatti Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Melatti, Robert N.. "Achieving Sourdough Status: The Diary, Photographs, and Letters of Samuel Baker Dunn, 1898-1899" (2016). Master of Arts (MA), Thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ mrs2-2135 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A ACHIEVING SOURDOUGH STATUS: THE DIARY, PHOTOGRAPHS, AND LETTERS OF SAMUEL BAKER DUNN, 1898-1899 by Robert Nicholas Melatti B.A. May 2011, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2016 Approved by: Elizabeth Zanoni (Director) Maura Hametz (Member) Ingo Heidbrink (Member) B ABSTRACT ACHIEVING SOURDOUGH STATUS: THE DIARY, PHOTOGRAPHS, AND LETTERS OF SAMUEL BAKER DUNN, 1898-1899 Robert Nicholas Melatti Old Dominion University, 2016 Director: Dr. Elizabeth Zanoni This thesis examines Samuel Baker Dunn and other prospectors from Montgomery County in Southwestern Iowa who participated in the Yukon Gold Rush of 1896-1899. -

Dp Harvey Milk

1 Focus Features présente en association avec Axon Films Une production Groundswell/Jinks/Cohen Company un film de GUS VAN SANT SEAN PENN HARVEY MILK EMILE HIRSCH JOSH BROLIN DIEGO LUNA et JAMES FRANCO Durée : 2h07 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 4 MARS 2008 Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.snd-films.com DISTRIBUTION : RELATIONS PRESSE : SND JEAN-PIERRE VINCENT 89, avenue Charles-de-Gaulle SOPHIE SALEYRON 92575 Neuilly-sur-Seine Cedex 12, rue Paul Baudry Tél. : 01 41 92 79 39/41/42 75008 Paris Fax : 01 41 92 79 07 Tél. : 01 42 25 23 80 3 SYNOPSIS Le film retrace les huit dernières années de la vie d’Harvey Milk (SEAN PENN). Dans les années 1970 il fut le premier homme politique américain ouvertement gay à être élu à des fonctions officielles, à San Francisco en Californie. Son combat pour la tolérance et l’intégration des communautés homosexuelles lui coûta la vie. Son action a changé les mentalités, et son engagement a changé l’histoire. 5 CHRONOLOGIE 1930, 22 mai. Naissance d’Harvey Bernard Milk à Woodmere, dans l’Etat de New York. 1946 Milk entre dans l’équipe de football junior de Bay Shore High School, dans l’Etat de New York. 1947 Milk sort diplômé de Bay Shore High School. 1951 Milk obtient son diplôme de mathématiques de la State University (SUNY) d’Albany et entre dans l’U.S. Navy. 1955 Milk quitte la Navy avec les honneurs et devient professeur dans un lycée. 1963 Milk entame une nouvelle carrière au sein d’une firme d’investissements de Wall Street, Bache & Co. -

Come Into My Parlor. a Biography of the Aristocratic Everleigh Sisters of Chicago

COME INTO MY PARLOR Charles Washburn LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN IN MEMORY OF STEWART S. HOWE JOURNALISM CLASS OF 1928 STEWART S. HOWE FOUNDATION 176.5 W27c cop. 2 J.H.5. 4l/, oj> COME INTO MY PARLOR ^j* A BIOGRAPHY OF THE ARISTOCRATIC EVERLEIGH SISTERS OF CHICAGO By Charles Washburn Knickerbocker Publishing Co New York Copyright, 1934 NATIONAL LIBRARY PRESS PRINTED IN U.S.A. BY HUDSON OFFSET CO., INC.—N.Y.C. \a)21c~ contents Chapter Page Preface vii 1. The Upward Path . _ 11 II. The First Night 21 III. Papillons de la Nun 31 IV. Bath-House John and a First Ward Ball.... 43 V. The Sideshow 55 VI. The Big Top .... r 65 VII. The Prince and the Pauper 77 VIII. Murder in The Rue Dearborn 83 IX. Growing Pains 103 X. Those Nineties in Chicago 117 XL Big Jim Colosimo 133 XII. Tinsel and Glitter 145 XIII. Calumet 412 159 XIV. The "Perfessor" 167 XV. Night Press Rakes 173 XVI. From Bawd to Worse 181 XVII. The Forces Mobilize 187 XVIII. Handwriting on the Wall 193 XIX. The Last Night 201 XX. Wayman and the Final Raids 213 XXI. Exit Madams 241 Index 253 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful appreciation to Lillian Roza, for checking dates John Kelley, for early Chicago history Ned Alvord, for data on brothels in general Tom Bourke Pauline Carson Palmer Wright Jack Lait The Chicago Public Library The New York Public Library and The Sisters Themselves TO JOHN CHAPMAN of The York Daily News WHO NEVER WAS IN ONE — PREFACE THE EVERLEIGH SISTERS, should the name lack a familiar ring, were definitely the most spectacular madams of the most spectacular bagnio which millionaires of the early- twentieth century supped and sported. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2328

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2328 ASCHENBROEDEL VEREIN (later GESANGVEREIN SCHILLERBUND/ now LA MAMA EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE CLUB) BUILDING, 74 East 4th Street, Manhattan Built 1873, August H. Blankenstein, architect; facade altered 1892, [Frederick William] Kurtzer & [Richard O.L.] Rohl, architects Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 459, Lot 23 On March 24, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Aschenbroedel Verein (later Gesangverein Schillerbund/ now La Mama Experimental Theatre Club) Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 11). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Four people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the Municipal Art Society of New York, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, and Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received a communication in support of designation from the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America. Summary The four-story, red brick-clad Aschenbroedel Verein Building, in today’s East Village neighborhood of Manhattan, was constructed in 1873 to the design of German-born architect August H. Blankenstein for this German-American professional orchestral musicians’ social and benevolent association. Founded informally in 1860, it had grown large enough by 1866 for the society to purchase this site and eventually construct the purpose-built structure. The Aschenbroedel Verein became one of the leading German organizations in Kleindeutschland on the Lower East Side. It counted as members many of the most important musicians in the city, at a time when German-Americans dominated the orchestral scene. -

Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates Over Urban Public Space

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates over Urban Public Space Anna Rascovar The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2019 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] WASHINGTON SQUARE PARK: STRUGGLES AND DEBATES OVER URBAN PUBLIC SPACE by ANNA RASCOVAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 ANNA RASCOVAR All Rights Reserved ii Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates over Urban Public Space by Anna Rascovar This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date David Humphries Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Washington Square Park: Struggles and Debates over Urban Public Space by Anna Rascovar Advisor: David Humphries Public space is often perceived as a space that is open to everyone and is meant for gatherings and interaction; however, there is often a great competition over the use and control of public places in contemporary cities. This master’s thesis uses as an example Washington Square Park, which has become a center of contention due to the interplay of public and private interests. -

LPC Designation Report for South Village Historic District

South Village Historic District Designation Report December 17, 2013 Cover Photographs: 200 and 202 Bleecker Street (c. 1825-26); streetscape along LaGuardia Place with 510 LaGuardia Place in the foreground (1871-72, Henry Fernbach); 149 Bleecker Street (c. 1831); Mills House No. 1, 156 Bleecker Street (1896-97, Ernest Flagg); 508 LaGuardia Place (1891, Brunner & Tryon); 177 to 171 Bleecker Street (1887-88, Alexander I. Finkle); 500 LaGuardia Place (1870, Samuel Lynch). Christopher D. Brazee, December 2013 South Village Historic District Designation Report Essay prepared by Christopher D. Brazee, Cynthia Danza, Gale Harris, Virginia Kurshan. Jennifer L. Most, Theresa C. Noonan, Matthew A. Postal, Donald G. Presa, and Jay Shockley Architects’ and Builders’ Appendix prepared by Marianne S. Percival Building Profiles prepared by Christopher D. Brazee, Jennifer L. Most, and Marianne S. Percival, with additional research by Jay Shockley Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Michael Devonshire Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS SOUTH VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP .............................................. FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 1 SOUTH