Len Berkman on the Caffe Cino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caffe Cino

DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 31 Cornelia Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE No. 31 Cornelia Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. During those ten years, the coffee shop served as an experimental theater venue, becoming the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and New York City’s first gay theater. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 Former location of the Caffe Cino, 31 Cornelia Street 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman PHOTOGRAPHS BY LPC Staff Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 3 of 24 The Caffe Cino the National Parks Conservation Association, Village 31 Cornelia Street, Manhattan Preservation, Save Chelsea, and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, and 19 individuals. No one spoke in opposition to the proposed designation. The Commission also received 124 written submissions in favor of the proposed designation, including from Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz, New York Designation List 513 City Council Member Adrienne Adams, the LP-2635 Preservation League of New York State, and 121 individuals. -

Wilson, Doric (B

Wilson, Doric (b. 1939) by Brandon Hayes Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com A portrait of Doric Wilson by Robert Giard. A pioneer in the development of contemporary gay theater, Doric Wilson has been Courtesy Doric Wilson. instrumental in Off-Off-Broadway theater in New York City since the early 1960s. Wilson uses theater as a means of anatomizing the lives of gay New Yorkers, particularly gay men, and to motivate his audiences toward activism. His most famous play, Street Theater (1981), is a heartfelt depiction of the Stonewall riots, in which Wilson took part. Wilson was born in Los Angeles on February 24, 1939. He was raised on his grandfather's ranch in Washington state. He attended high school in Kennewick, Washington, where he came out in the 1950s. He has ever since lived as an out gay man. Wilson trained for a short time in the Drama Department at the University of Washington. He was asked to leave the university in 1958 after he protested anti-gay harassment at a local park. Wilson moved to New York City in 1958, where, under the mentorship of producer Richard Barr, he became active in the burgeoning Off-Off-Broadway theater scene. Along with Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson, he was involved in Caffe Cino, a coffee shop and theatrical space owned by producer Joe Cino. In 1961, Wilson's first major play, And He Made a Her, opened at Caffe Cino. Wilson became a founding member of Circle Repertory Theatre and the Barr/Wilder/Albee Playwright's Unit. -

Broadside 12:L

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION - - - - - - - - - Volume 12, Number 2 Fall 1984 New Series THE CAFFE ClNO AND ITS LEGACY: OFF-OFF BROADWAY IS FOCUS OF EXHIBITION Richard M. Buck, the Theatre Library Association's tireless and dedicated Secre- tary-Treasurer, has put together an extraor- dinary exhibition detailing the history and heyday of the Caffce Cino, m Qff-Off Broadway playhouse which was the inspir- ation for a new movement in the theatre. The exhibition, which will be on view in the Vincent Astor Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center until May 15, follows former TLA board member William Appleton's splendid exhibition on the life and career of composer Richard Rodgers. The Caffe Cino flourished at 31 Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village, New York City, from 1959 to 1968. Beginning with the earliest days when the Cino was a poetry- reading cafe, the exhibition carries the story of the Cino to its end, when after founder Joe Cino's tragic death in 1967, a loyal group of followers tried to continue the tradition. Along the way, the viewer will discover many names and titles that have become landmarks in theatre history: Lanford Wilson, Tom Eyen, John Guare, Sam Shepard, Robert Patrick, Dames at Stewart, Robert Patrick, Robert Heide, Hoffman will discuss the impact of the Sea, This is the Rill Speaking, The White Robert Dahdah, Shirley Stoler, and many Cino on theatre that followed. The pro- Whore and the Bit Player, and many, many others who have first-hand memories of grams, which will begin at 6:30 p.m., will more. -

Wilson, Doric (1939-2011) by Brandon Hayes

Wilson, Doric (1939-2011) by Brandon Hayes Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com A portrait of Doric Wilson by Robert Giard. A pioneer in the development of contemporary gay theater, Doric Wilson was Courtesy Doric Wilson. instrumental in Off-Off-Broadway theater in New York City frin the early 1960s through the 1980s. Wilson used theater as a means of anatomizing the lives of gay New Yorkers, particularly gay men, and to motivate his audiences toward activism. His most famous play, Street Theater (1981), is a heartfelt depiction of the Stonewall riots, in which Wilson took part. Wilson was born in Los Angeles on February 24, 1939. He was raised on his grandfather's ranch in Washington state. He attended high school in Kennewick, Washington, where he came out in the 1950s. He ever since lived as an out gay man. Wilson trained for a short time in the Drama Department at the University of Washington. He was asked to leave the university in 1958 after he protested anti-gay harassment at a local park. Wilson moved to New York City in 1958, where, under the mentorship of producer Richard Barr, he became active in the burgeoning Off-Off-Broadway theater scene. Along with Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson, he was involved in Caffe Cino, a coffee shop and theatrical space owned by producer Joe Cino. In 1961, Wilson's first major play, And He Made a Her, opened at Caffe Cino. Wilson became a founding member of Circle Repertory Theatre and the Barr/Wilder/Albee Playwright's Unit. -

God at the Drafting Board Airy Public Housing Units Were Built

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 14, NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2018 $1.00 years ago, under LaGuardia and Roosevelt, ancient tenements came down through slum clearance, and the first, nice, clean, God at the Drafting Board airy public housing units were built. How- By George Capsis ever, the bureaucratic solution of one era becomes the bane of the next, so we now If God sat down at the drafting board to have one million residents and three gen- design a perfect solution for seniors now erations living in NYCHA Land, all with a living alone in a five-story walk-up, with an vested interest in maintaining poverty. ancient dog that has to go four times a day, So, right now if you offer a West Village what would He come up with? He would senior an apartment off in some foreign have a nice, fresh-faced youngster offer a neighborhood like Chelsea or SoHo, he strong arm to help our ancient walk to the will hesitate and demur, “Uh, it’s not the doctor and take Fido to happily meet his West Village. This is my home,” and fight target hydrant for even a fifth visit. to keep his mouse-central apartment. Unfortunately, God does not work in So, okay, God sits down at the drafting City Planning. So, we hear a moaning cho- board for the many seniors facing eviction rus of West Village seniors once happy for and/or a heart attack to design the ideal the fifth floor view and now working up apartment and the ideal companion. -

The Caffe Cino (Block 590, Lot 30), by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on June 18, 2019 (Designation List No

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION August 14, 2019 / Calendar No. 33 N 190534 HIM IN THE MATTER OF a communication dated June 27, 2019, from the Executive Director of the Landmarks Preservation Commission regarding the landmark designation of The Caffe Cino (Block 590, Lot 30), by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on June 18, 2019 (Designation List No. 513/LP-2635), Borough of Manhattan, Community District 2. Pursuant to Section 3020.8(b) of the City Charter, the City Planning Commission shall submit to the City Council a report with respect to the relation of any designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, whether of a historic district or a landmark, to the Zoning Resolution, projected public improvements, and any plans for the development, growth, improvement or renewal of the area involved. On June 18, 2019, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the Caffe Cino, located at 31 Cornelia Street (Block 590, p/o Lot 47) as a City landmark. The landmark site is located on the west side of Cornelia Street between Bleecker and West 4th streets, within Manhattan Community District 2. The Caffe Cino is one of six buildings that the LPC designated as individual landmarks for their historical significance to the LGBT community. On the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots and coinciding with World Pride NYC, LPC recognized these sites as places associated with groups and individuals that helped move forward the LGBT civil rights movement by creating political and community support structures and by bringing LGBT cultural expression into the public realm. 31 Cornelia Street, located between Bleecker and West 4th streets in Manhattan, is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground-floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. -

Greenwich Village Historic District Extension II Designation Report

Cover Photograph: Father Demo Square and Our Lady of Pompeii Church (Matthew Del Gaudio, 1926-28), Bleecker and Carmine Streets Christopher D. Brazee, 2010 Greenwich Village Historic District Extension II Designation Report Essay researched and written by Olivia Klose Architects’ and Builders’ Appendix researched and written by Marianne Percival Building Profiles by Olivia Klose, Virginia Kurshan, and Marianne Percival Editorial Assistance by Christopher D. Brazee Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Pablo E. Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Stephen F. Byrns Margery Perlmutter Diana Chapin Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Roberta Brandes Gratz Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS GREENWICH VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION II MAP ...................... FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING .............................................................................................. 1 GREENWICH VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION II BOUNDARIES ................................ 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 3 HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREENWICH VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION II ........................................................................................................................................... -

A Background to Balm in Gilead

A Background to Balm in Gilead: A little bit of information to give you a deeper look at the time, place, and themes in the play 1 | Page Table of Contents Lanford Wilson ............................................................................... Page 3 Balm in Gilead ................................................................................ Page 6 Book of Jeremiah ........................................................................... Page 7 1960s ............................................................................................... Page 9 History of New York City (1946–1977) ........................................ Page 30 Classic ‘New York’: The 1960s .................................................... Page 35 Important Events of the 1960s .................................................... Page 37 Heroin ............................................................................................ Page 46 2 | Page Lanford Wilson (1937- ) American playwright. The following entry provides an overview of Wilson's career through 2003. For further information on his life and works, see CLC, Volumes 7, 14, and 36. INTRODUCTION A prolific writer of experimental and traditional drama, Wilson launched his career at the avant-garde Caffe Cino during the off-off-Broadway movement of the 1960s. He later co-founded the renowned Circle Repertory Company, for which he wrote many of his major works, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning Talley's Folly (1979). Through his dynamic characters, many of whom are misfits of low social -

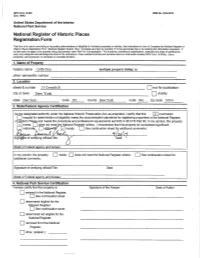

Caffe Cino Multiple Property Listing: No Other Names/Site Number 2

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Caffe Cino multiple property listing: no other names/site number 2. Location street & number 31 Cornelia St not for publication city or town New York vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10014 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this x nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide x locally. -

Playing Underground: a Critical History of the 1960'S Off-Off-Broadway Movement Philip C

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Faculty Publications 12-1-2005 Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960's Off-Off-Broadway Movement Philip C. Kolin University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/fac_pubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kolin, P. C. (2005). Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960's Off-Off-Broadway Movement. Theatre Journal, 57(4), 780-781. Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/fac_pubs/2597 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 780 / Book Review practical guide to how performances are written, mark") took over "the job of putting on the far staged, or filmed. Where Hatchuel is interested in thest, most risky plays of young writers restless" the nuts and bolts of how a director transforms with other theatres (83). As a result of Bottoms's Shakespeare for cinema, Aebischer wants to ques exhaustive search for scripts, reviews, and a series tion the tools of that transformation and the result of interviews with forty playwrights, directors, and ing mechanism itself. Shakespeare's Violated Bodies actors, he captures the Off Off movement by focus ends with a short return to her stated purpose: she ing on the complex relationships among the people, means to turn "stories of loss into stories of re venues, and plays at four theatres?Caffe Cino, membrance, resistance, hope and gain" (190). -

Study Guide For

Study Guide for Written by Sophie Watkiss Edited by Rosie Dalling Rehearsal photography by Marc Brenner Production photography by Hugo Glendining This programme has been made possible by the generous support of The Bay Foundation, Noel Coward Foundation and Universal Consolidated Group 1 Contents Section 1: Cast and Creative Team Section 2: Lanford Wilson and a New American Theatre Off-Off Broadway The style of Lanford Wilson’s work An introduction to SERENADING LOUIE The quartet of characters Section 3: Inside the rehearsal room Design concept A conversation with Ben Woolf, Associate Director Section 4: Practical work Act One, Scenes One and Two Section 5: Bibliography and endnotes 2 section 1 Cast and Creative Team Cast Charlotte Emmerson: MARY Theatre: includes Wallenstein (Chichester Festival), On the Rocks (Hampstead), The Children’s Hour, Great Expectations (Manchester Royal Exchange), Therese Raquin, The Coast of Utopia, The Good Hope, The Cherry Orchard (NT), The Daughter-in-Law (Watford Palace), Postman Always Ring Twice (Playhouse/ WYP), The Seagull (Edinburgh Festival), Our Song (TEG Productions), Baby Doll (Birmingham Rep/NT/Albery), The Crucible (tour). Film: includes The Last Minute, Smile, Weekend Bird, Food of Love, Wangle. Television: includes Casualty 1909, Berry’s Way, The Innocent Project, Stan, See No Evil, Midsomer Murders, Vincent, Outlaws, The Brief, Foyles War, The Alan Clark Diaries, Holby City, Peak Practise, Just Desserts, Noah’s Ark, The Lives and Crimes of William Palmer, Underworld, Staying Alive. Jason -

LGBTQ Playwrights Respond to Bullying and Teen Suicide Written by Kevin Cristopher Crowe Has Been Approved for the Department of Theatre & Dance

WORDS THAT WOUND: LGBTQ PLAYWRIGHTS RESPOND TO BULLYING AND TEEN SUICIDE By KEVIN CHRISTOPHER CROWE B.A., Stony Brook University, 1998 M.F.A., Humboldt State University, 2003 M.S., Portland State University, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment Of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre & Dance 2017 This thesis entitled: Words That Wound: LGBTQ Playwrights Respond to Bullying and Teen Suicide Written by Kevin Cristopher Crowe has been approved for the Department of Theatre & Dance ______________________________________________________ Dr. Beth Osnes (Committee Chair) ______________________________________________________ Dr. Bud Coleman ______________________________________________________ Dr. Amanda Giguere ______________________________________________________ Dr. Lynn Nichols ______________________________________________________ Dr. Cecilia Pang Date: __________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the forms meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above-mentioned discipline. iii Abstract Kevin Cristopher Crowe (Ph.D.; Theatre) Words That Wound: LGBTQ Playwrights Respond to Bullying and Teen Suicide Thesis directed by Associate Professor Beth Osnes This research looks at how playwrights within a specific and unique community use theatre to address challenges faced by that community to bring about positive change. Specifically, this investigation focuses on the American LGBTQ community, who have historically demonstrated a high level of success in using theatre to bring public awareness to specific issues, such as homophobia and AIDS, and how playwrights within that community are currently dealing with the ongoing crisis of teen suicide and bullying, particularly in light of a string of LGBTQ bullying-related suicides in September 2010.