Designing Ocean Parks for the Next Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

Stone Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Vision Statement

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Stone Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Vision Statement Stone Lakes National Wildlife Refuge belongs to a limited group among the 540 national wildlife refuges that protect fish, wildlife, and habitat within an urban area. Through collaboration with public and private partners, Stone Lakes conserves and enhances a range of scarce Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Central Valley habitats and the fish, wildlife, and plants they support. It sustains freshwater wetlands, wooded riparian corridors, and grasslands that facilitate wildlife movement and compensate for habitat fragmentation. Managed wetlands are of sufficient size to maintain abundant wildlife populations. Grasslands consist of a sustainable mix of native and desirable nonnative species that support a variety of grassland-dependent species. The Refuge reduces further habitat fragmentation and buffers the effects of urbanization on agricultural lands and adjacent natural areas within the Delta region. The Refuge pursues a land conservation program that complements other regional efforts and initiatives. Management efforts expand and diversify habitats for migratory birds and a range of species at risk. The Refuge promotes cooperative farming opportunities and strives to maintain traditional agricultural practices in southwestern Sacramento County that have proven benefits for migratory birds experiencing declines, such as long-billed curlews (Numenius americanus), Swainson’s hawks (Buteo swainsoni) and sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis). Through cooperation with other agencies, conservation organizations, neighbors, and other partners, the Refuge develops and manages wetlands in a manner that reflects historic hydrologic patterns and is consistent with local, State, and Federal floodplain management goals and programs. Stone Lakes was established as a national wildlife refuge because of passionate support from people who recognized its ecological importance and critical role for the floodplain of the Beach-Stone Lakes basin. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Yellowstone Center for Resources

YELLOWSTONE CENTER FOR RESOURCES SPATIAL A naly sis es rc u o s RESOUR e CE R N L A T A U R R U A T L L U R e C s o u r r c c e s I nfo rmation R ES EA RCH Support ANNUAL2001 REPORT YELLOWSTONE CENTER FOR RESOURCES 2001 ANNUAL REPORT Hand-painted Limoges bowl, Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, ca. 1910. Part of the Davis Collection acquired in 2001. Yellowstone Center for Resources National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR–AR–2001 2002 In memory of Donay Hanson 1960–2001 Suggested Citation: Yellowstone Center for Resources. 2002. Yellowstone Center for Resources Annual Report, 2001. National Park Service, Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming, YCR–AR–2001. Photographs not otherwise marked are courtesy of the National Park Service. Front cover: clockwise from top right, Beatrice Miles of the Nez Perce Tribe; Yellowstone cutthroat trout; Golden Gate Bridge by W. Ingersoll, circa 1880s, from the Susan and Jack Davis Collection; low northern sedge (Carex concinna) by Jennifer Whipple; and center, Canada lynx. Back cover: mountain chickadee. ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................ iv Part I. Resource Highlights ............................................................................... 1 Part II. Cultural Resource Programs ............................................................... 7 Archeology ...................................................................................................... 8 Ethnography ................................................................................................. -

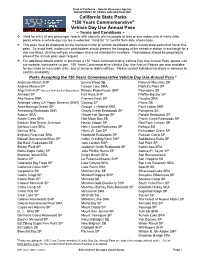

California State Parks Volunteer District and Statewide Passes

State of California – Natural Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION California State Parks Volunteer District and Statewide Passes California’s State Park System is the largest in the country, offering some of the world’s most varied natural and cultural wonders. Volunteers are vital to California’s State Parks. Tens of thousands of volunteers donate over one million hours of time every year. As a means of showing appreciation for these volunteer efforts, California State Parks’ offers Volunteer District and Statewide Passes to those who meet minimum requirements. Please observe the terms and conditions listed below that apply to this pass and its use. Violation of the terms and conditions could result in pass revocation. Parks Accepting the Volunteer District* and Statewide Passes** *District pass holders may only use their pass at the parks listed below that fall within the district named on the front of their Volunteer District Pass. Andrew Molera SP Castle Rock SP Hungry Valley SVRA Angel Island SP (day use boat dock at Caswell Memorial SP Huntington SB finger piers only) China Camp SP Indian Grinding Rock SHP Ano Nuevo SP Chino Hills SP Jack London SHP Antelope Valley California Poppy Clay Pit SVRA Jedidiah Smith Redwoods SP Reserve SNR Clear Lake SP Julia Pfeiffer Burns SP Antelope Valley Indian Museum SHP Colonel Allensworth SHP Kings Beach SRA Anza-Borrego Desert SP Crystal Cove SP La Purisima Mission SHP Armstrong Redwoods SNR Cuyamaca Rancho SP Lake Oroville SRA Auburn SRA D. L. Bliss SP Lake Perris SRA Austin -

Units by Classification

CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS UNITS BY CLASSIFICATION CULTURAL PRESERVES (CP): Marina SB (Marina Dunes NP) McGrath SB (Santa Clara Estuary NP) Carmel River SB (Ohlone Coastal CP) Montaña de Oro SP (Morro Dunes NP) Cuyamaca Rancho SP (Ah-Ha-Kwe-Ah-Mac/Stone- Morro Bay SP (Heron Rookery NP, Morro Estuary wall Mine CP, Cuish-Cuish CP, Kumeyaay Soapstone NP, Morro Rock NP) CP, Pilcha CP) Mount San Jacinto SP (Hidden Divide NP) Hungry Valley SVRA (Freeman Canyon CP, Gorman Natural Bridges SB (Monarch Butterfly NP, Moore CP, Tataviam CP) Creek Wetland NP) Millerton Lake SRA (Kechaye CP) Palomar Mountain SP (Doane Valley NP) Mount Diablo SP (Civilian Conservation Corps CP) Pescadero SB (Pescadero Marsh NP) Ocotillo Wells SVRA (Barrel Springs CP) Pismo SB (Pismo Dunes NP) San Simeon SP (Pâ-nu CP) Point Mugu SP (La Jolla Valley NP) Wilder Ranch SP (Wilder Dairy CP) Providence Mountains SRA (Mitchell Caverns NP) Red Rock Canyon SP (Hagen Canyon NP, Red Cliffs NATURAL PRESERVES (NP): NP) Salinas River SB (Salinas River Dunes NP, Salinas Anderson Marsh SHP (Anderson Marsh NP) River Mouth NP) Benicia SRA (Southampton Wetland NP) San Onofre SB (Trestles Wetlands NP) Big Basin Redwoods SP (Theodore J. Hoover NP) San Simeon SP (San Simeon NP, Santa Rosa Creek Border Field SP (Tijuana Estuary NP) NP) Burton Creek SP (Antone Meadows NP, Burton Silver Strand SB (Silver Strand NP) Creek NP) Sugar Pine Point SP (Edwin L. Z’berg NP) Calaveras Big Trees SP (Calaveras South Grove Sunset SB (Sunset Wetlands NP) NP) Torrey Pines SR (Ellen Browning Scripps NP, Los Carmel River SB (Carmel River Lagoon and Wet- Peñasquitos Marsh NP) land NP) Van Damme SP (Van Damme Pygmy Forest NP) Castle Rock SP (San Lorenzo Headwaters NP) Wilder Ranch SP (Wilder Beach NP) Chino Hills SP (Water Canyon NP) Woodson Bridge SRA (Woodson Bridge NP) Cuyamaca Rancho SP (Cuyamaca Meadow NP) Zmudowski SB (Pajaro River Mouth NP) Folsom Lake SRA (Anderson Island NP, Mormon Island Wetlands NP) REGIONAL INDIAN MUSEUMS: Harry A. -

TOTALS = 1,691 175,767 AVERAGES = 35 3,587 7.6 48% 8% 23% 1% 20% 48% AL ALBAMA STATE PARKS (22 State Parks)

Reserve State # Parks # Sites Rating % 40+ ft % EWS % EW % W % E % NONE America? 1 Louisiana (LA) 21 2,147 8.4 67% 5% 58% 1% 5% 31% Yes 2 Arizona (AZ) 15 1,426 8.4 7% 43% 0% 26% 24% No 3 Nevada (NV) 17 521 8.3 5% 4% 0% 0% 91% No 4 North Dakota (ND) 11 500 8.3 94% 3% 80% 4% 2% 11% No 5 Arkansas (AR) 33 1,786 8.2 27% 61% 0% 0% 12% No 6 South Dakota (SD) 49 3,800 8.1 87% 0% 0% 0% 88% 12% No 7 Georgia (GA) 41 3,124 8.1 68% 1% 71% 0% 5% 23% Yes 8 Maryland (MD) 18 2,289 8.1 28% 1% 1% 0% 21% 77% Yes 9 Virginia (VA) 25 2,403 8.1 37% 5% 42% 0% 3% 50% Yes 10 Texas (TX) 70 6,975 8.0 11% 53% 13% 0% 23% No 11 Oregon (OR) 41 5,948 8.0 56% 23% 37% 0% 3% 37% Yes 12 Minnesota (MN) 62 3,943 8.0 70% 4% 0% 0% 40% 56% No 13 Vermont (VT) 39 2,152 8.0 6% 0% 0% 0% 0% 100% No 14 Alabama (AL) 22 2,336 7.9 61% 39% 0% 0% 0% No 15 Utah (UT) 30 2,063 7.9 30% 18% 14% 0% 6% 62% Yes 16 Illinois (IL) 48 5,391 7.9 64% 14% 0% 0% 68% 18% Yes 17 Kansas (KS) 22 7,021 7.9 64% 6% 33% 0% 5% 56% Yes 18 Idaho (ID) 17 1,883 7.8 40% 7% 44% 0% 3% 46% Yes 19 Colorado (CO) 41 4,258 7.8 63% 13% 2% 0% 43% 42% Yes 20 Florida (FL) 54 3,287 7.8 42% 14% 77% 0% 1% 8% Yes 21 Missouri (MO) 39 3,512 7.8 95% 5% 2% 0% 65% 28% No 22 North Carolina (NC) 16 2,792 7.8 68% 0% 43% 0% 1% 56% Yes 23 New Hampshire (NH) 17 1,127 7.7 9% 2% 7% 0% 0% 91% Yes 24 Maine (ME) 12 777 7.7 13% 0% 14% 0% 0% 86% No 25 South Carolina (SC) 33 3,182 7.7 34% 3% 72% 0% 0% 25% Yes 26 Oklahoma (OK) 41 5,119 7.7 No 27 Pennsylvania (PA) 47 5,784 7.7 41% 0% 0% 0% 49% 51% No 28 Indiana (IN) 32 8,275 7.6 63% 3% 0% 0% 76% 21% Yes -

Nature and Culture at Fishing Bridge: a History of the Fishing Bridge Devel- Opment in Yellowstone National Park

Schullery Paul Nature and Culture at Fishing Bridge Nature and Culture at Fishing Bridge at Fishing and Culture Nature A HISTORY OF T H E FISHING BRIDGE DEVELOPMENT IN YELLOWSTONE NA TION A L PA RK By Paul Schullery National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-2010-02 2010 Nature and Culture at Fishing Bridge A HISTORY OF T H E FISHING BRIDGE DEVELOPMENT IN YELLOWSTONE NA TION A L PA RK By Paul Schullery National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-2010-02 Front Cover: Left: The “second” Fishing Bridge as it appeared in the 1920s was nearly identical in general features to the original. Note that a floating dock was at this date moored on the downstream side of the bridge near the east bank, and was used by small boats (NPS photo, YELL 171144). Center: Fishermen crowd the railing at Fishing Bridge, early 1960s (NPS Photo, YELL 01902). Right: The ecological inseparability of landscape elements near Fishing Bridge has vexed genera- tions of managers and park constituents seeking simple and yet unified approaches to managing this area. The Fishing Bridge development is just to the east (right) of the bridge in this 2001 photograph. The large open area in the center of the photograph is the site of the former cabin area, and several miles of the Pelican Valley are visible across the top of the photograph (NPS photo by Jim Peaco, YELL 17339). Previous page: The original Fishing Bridge boathouse was, according to the superintendent, a “floating dock with office and sleeping quarters.” Steps led from the bridge down to the dock, where rental boats were tethered. -

REQUEST for QUALIFICATIONS No

REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS No. C08E0019 Architectural and Engineering Professional Services for Projects in the California State Park System November 2008 State of California Department of Parks and Recreation Acquisition and Development Division State of California Request for Qualifications No. C08E0019 Department of Parks and Recreation Architectural and Engineering Professional Services Acquisition and Development Division for Projects in the California State Parks System TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page SECTION 1 – GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Type of Professional Services......................................................................................... 3 1.3 RFQ Issuing Office .......................................................................................................... 5 1.4 SOQ Delivery and Deadline ............................................................................................ 5 1.5 Withdrawal of SOQ.......................................................................................................... 6 1.6 Rejection of SOQ ............................................................................................................ 6 1.7 Awards of Master Agreements ........................................................................................ 6 SECTION 2 – SCOPE OF WORK 2.1 Locations and Descriptions of Potential Projects ........................................................... -

"150 Years Commemorative" Vehicle Day Use Annual Pass

State of California – Natural Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION California State Parks "150 Years Commemorative" Vehicle Day Use Annual Pass ~ Terms and Conditions ~ Valid for entry of one passenger vehicle with capacity of nine people or less or one motorcycle at many state parks where a vehicle day use fee is collected. Valid for 12 months from date of purchase. This pass must be displayed on the rearview mirror or vehicle dashboard when visiting state parks that honor this pass. To avoid theft, motorcycle passholders should present the hangtag at the entrance station in exchange for a day use ticket, utilizing self-pay envelopes where no attendant is available. Passholders should be prepared to present the annual pass upon request. For additional details and/or to purchase a 150 Years Commemorative Vehicle Day Use Annual Pass, please visit our website, www.parks.ca.gov. 150 Years Commemorative Vehicle Day Use Annual Passes are also available for purchase at many park units, and at sector or district offices. Please contact individual locations in advance to confirm availability. Parks Accepting the 150 Years Commemorative Vehicle Day Use Annual Pass * Anderson Marsh SHP Emma Wood SB Palomar Mountain SP Andrew Molera SP Folsom Lake SRA Patrick's Point SP Angel Island SP (day use boat dock at finger piers) Folsom Powerhouse SHP Pescadero SB Annadel SP Fort Ross SHP Pfeiffer Big Sur SP Año Nuevo SNR Fremont Peak SP Picacho SRA Antelope Valley CA Poppy Reserve (SNR) Gaviota SP Pismo SB Anza-Borrego Desert SP George J. Hatfield SRA Point Lobos SNR Armstrong Redwoods SNR Grizzly Creek Redwoods SP Pomponio SB Auburn SRA Grover Hot Springs SP Portola Redwoods SP Austin Creek SRA Half Moon Bay SB Prairie Creek Redwoods SP Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook Hendy Woods SP Red Rock Canyon SP Benbow Lake SRA Henry Cowell Redwoods SP Refugio SB Benicia SRA Henry W. -

Chapter 2. Resource and Land Use Inventory

Chapter 2. Resource and Land Use Inventory This chapter describes key natural resource and land-use factors and characteristics affecting the Bufferlands. These provide the context and the basis for the management directions outlined in Chapters 4 and 5. In separate sections, this chapter describes soils and geology, hydrology and water quality, vegetation and wildlife, visual resources, cultural resources, existing land use, and public use and security. SOILS Soil characteristics, such as depth, texture, drainage and surface relief influence the suitability of an area for use in agriculture, livestock grazing, or habitat restoration. This section provides a general description of soils in the Bufferlands and their relative suitability for agricultural use and habitat restoration. Information from the Soil Survey of Sacramento County, California (Soil Conservation Service 1993) was used to assess the suitability of the soils for agricultural use and habitat restoration and to determine soil-related constraints on habitat restoration. The following soil types identified in the soil survey of Sacramento County (Soil Conservation Service 1993) are found on the Bufferlands: the Clear Lake and Egbert clays, Dierrsen sandy clay loam and clay loam, Madera loam, San Joaquin silt loam, and Galt clay. These soil types are discussed below. Clear Lake and Egbert Clays These soils, the most productive found in the Bufferlands, occupy low elevations in Beach Lake and on the floodplains of Morrison, Laguna, and Beacon Creeks (Figure 2–1). The main limitations of these soils are shallow depths to the water table, fine surface texture, slow permeability, and slow runoff, all of which contribute to frequent flooding in some areas. -

Planning Milestones for the Park Units and Major Properties Associated with the California State Park System

Planning Milestones for the Park Units and Major Properties Associated with the CALIFORNIA STATE PARK SYSTEM July 1, 2019 Strategic Planning and Recreation Services Division Recreation Planning Unit California State Parks P. O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 PLANNING MILESTONES FOR THE PARK UNITS AND MAJOR PROPERTIES ASSOCIATED WITH THE CALIFORNIA STATE PARK SYSTEM July 1, 2019 OVERVIEW This document is a compendium providing selected information on the classified units and major unclassified properties that currently are or have in the past been associated with the California State Park System*. The main purposes of this compendium are to provide, in a single source: 1. a record of the major milestones and achievements in unit-level land use and management planning that have been accomplished through the years by the Department, with the major accomplishments of the last year summarized in Chapter II; 2. a variety of other information useful to understanding the past history or current status of these units and properties, and of the evolution of unit-level land use and resource management planning in the Department; and 3. the definitive number and the specific identity of those basic classified units and major unclassified properties that constitute the official State Park System as of the date of this report’s publication. As of July 1, 2019, the California State Park System consists of 280 basic classified units and major unclassified properties. These units and properties are identified on Lists 1 and 2 in Chapter III. To have data current to July 1, 2019, this total will be the Department’s official figure until the next edition of this report.