French Colonial Trade Patterns: Facts and Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

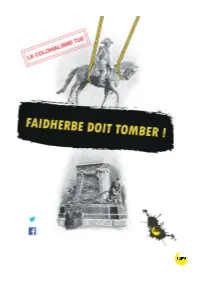

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Looters Vs. Traitors: the Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and Its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire

Looters vs. Traitors: The Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire Abstract: Since 2012, when broadcasting licenses were granted to various private television and radio stations in Mauritania, the controversy around the Battle of Um Tounsi (and Mauritania’s colonial past more generally) has grown substantially. One of the results of this unprecedented level of media freedom has been the prop- agation of views defending the Mauritanian resistance (muqawama in Arabic) to French colonization. On the one hand, verbal and written accounts have emerged which paint certain groups and actors as French colonial power sympathizers. At the same time, various online publications have responded by seriously questioning the very existence of a structured resistance to colonization. This article, drawing pre- dominantly on local sources, highlights the importance of this controversy in study- ing the western Saharan region social model and its contemporary uses. African Studies Review, Volume 63, Number 2 (June 2020), pp. 258– 280 Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba is Professor of History and Sociolinguistics at the University of Nouakchott, Mauritania (Ph.D. University of Provence (Aix- Marseille I); Fulbright Scholar resident at Northwestern University 2012–2013), and a Senior Research Consultant at the CAPSAHARA project (ERC-2016- StG-716467). E-mail: [email protected] Francisco Freire is an Anthropologist (Ph.D. Universidade Nova de Lisboa 2009) at CRIA–NOVA FCSH (Lisbon, Portugal). He is the Principal Investigator of the European Research Council funded project CAPSAHARA: Critical Approaches to Politics, Social Activism and Islamic Militancy in the Western Saharan Region (ERC-2016-StG-716467). -

Crime, Punishment, and Colonization: a History of the Prison of Saint-Louis and the Development of the Penitentiary System in Senegal, Ca

CRIME, PUNISHMENT, AND COLONIZATION: A HISTORY OF THE PRISON OF SAINT-LOUIS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PENITENTIARY SYSTEM IN SENEGAL, CA. 1830-CA. 1940 By Ibra Sene A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY HISTORY 2010 ABSTRACT CRIME, PUNISHMENT, AND COLONIZATION: A HISTORY OF THE PRISON OF SAINT-LOUIS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PENITENTIARY SYSTEM IN SENEGAL, CA. 1830-CA. 1940 By Ibra Sene My thesis explores the relationships between the prison of Saint-Louis (Senegal), the development of the penitentiary institution, and colonization in Senegal, between ca. 1830 and ca. 1940 . Beyond the institutional frame, I focus on how the colonial society influenced the implementation of, and the mission assigned to, imprisonment. Conversely, I explore the extent to which the situation in the prison impacted the relationships between the colonizers and the colonized populations. First, I look at the evolution of the Prison of Saint-Louis by focusing on the preoccupations of the colonial authorities and the legislation that helped implement the establishment and organize its operation. I examine the facilities in comparison with the other prisons in the colony. Second, I analyze the internal operation of the prison in relation to the French colonial agenda and policies. Third and lastly, I focus on the ‘prison society’. I look at the contentions, negotiations and accommodations that occurred within the carceral space, between the colonizer and the colonized people. I show that imprisonment played an important role in French colonization in Senegal, and that the prison of Saint-Louis was not just a model for, but also the nodal center of, the development of the penitentiary. -

The Slow Death of Slavery in Nineteenth Century Senegal and the Gold Coast

That Most Perfidious Institution: The slow death of slavery in nineteenth century Senegal and the Gold Coast Trevor Russell Getz Submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School or Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10673252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673252 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract That Most Perfidious Institution is a study of Africans - slaves and slave owners - and their central roles in both the expansion of slavery in the early nineteenth century and attempts to reform servile relationships in the late nineteenth century. The pivotal place of Africans can be seen in the interaction between indigenous slave-owning elites (aristocrats and urban Euro-African merchants), local European administrators, and slaves themselves. My approach to this problematic is both chronologically and geographically comparative. The central comparison between Senegal and the Gold Coast contrasts the varying impact of colonial policies, integration into the trans-Atlantic economy; and, more importantly, the continuity of indigenous institutions and the transformative agency of indigenous actors. -

The West Indian Mission to West Africa: the Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963

The West Indian Mission to West Africa: The Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963 by Bakary Gibba A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Bakary Gibba (2011) The West Indian Mission to West Africa: The Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963 Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Bakary Gibba Department of History, University of Toronto Abstract This thesis investigates the efforts of the West Indian Church to establish and run a fascinating Mission in an area of West Africa already influenced by Islam or traditional religion. It focuses mainly on the Pongas Mission’s efforts to spread the Gospel but also discusses its missionary hierarchy during the formative years in the Pongas Country between 1855 and 1863, and the period between 1863 and 1873, when efforts were made to consolidate the Mission under black control and supervision. Between 1873 and 1900 when additional Sierra Leonean assistants were hired, relations between them and African-descended West Indian missionaries, as well as between these missionaries and their Eurafrican host chiefs, deteriorated. More efforts were made to consolidate the Pongas Mission amidst greater financial difficulties and increased French influence and restrictive measures against it between 1860 and 1935. These followed an earlier prejudiced policy in the Mission that was strongly influenced by the hierarchical nature of nineteenth-century Barbadian society, which was abandoned only after successive deaths -

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal –

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal – Key terms: Assimilation Association Direct rule Mission Dakar–Djibouti Direct Rule Direct rule is a system whereby the colonies were governed by European officials at the top position, then Natives were at the bottom. The Germans and French preferred this system of administration in their colonies. Reasons: This system enabled them to be harsh and use force to the African without any compromise, they used the direct rule in order to force African to produce raw materials and provide cheap labor The colonial powers did not like the use of chiefs because they saw them as backward and African people could not even know how to lead themselves in order to meet the colonial interests It was used to provide employment to the French and Germans, hence lowering unemployment rates in the home country Impacts of direct rule It undermined pre-existing African traditional rulers replacing them with others It managed to suppress African resistances since these colonies had enough white military forces to safeguard their interests This was done through the use of harsh and brutal means to make Africans meet the colonial demands. Assimilation (one ideological basis of French colonial policy in the 19th and 20th centuries) In contrast with British imperial policy, the French taught their subjects that, by adopting French language and culture, they could eventually become French and eventually turned them into black Frenchmen. The famous 'Four Communes' in Senegal were seen as proof of this. Here Africans were granted all the rights of French citizens. -

British and French Styles of Influence in Colonial and Independent Africa

British and French Styles of Influence in Colonial and Independent Africa: A Comparative Study of Kenya and Senegal Laura Fenwick SIS 419 002: Honors Capstone Dr. Patrick Ukata 23 April 2009 Fenwick 2 Introduction The goal of colonialism was universal: extract economic benefits for the colonizing government. However, France and England had fundamentally different approaches to their colonial rule. While England wanted to exploit resources and create a profitable environment for its settler communities, France espoused an additional goal of transforming the African populations within its sphere of influence into French citizens. Nowhere is this effort epitomized better than in Senegal. These different approaches affected the type of colonial rule and the post- colonial relationship in an elemental way. The two powers had many similarities in their colonial rule. They imposed direct rule, limiting rights of the African peoples. The colonial administrations established a complementary economy based on exporting raw goods and importing manufactured goods. They introduced European culture and taught their own history in schools. France, however, took the idea of a united French Empire a step further with the policy of assimilation. Reeling from the ideals of equality from the 1848 Revolution, the French Republic granted political rights and citizenship for francisé (Frenchified) Africans. Its rule in West Africa was characterized by an unprecedented degree of political representation for Blacks. The English government did not grant this amount of political rights until the final years of colonial rule, when international and domestic pressures for decolonization were mounting. French West African colonies enjoyed their close economic, political, and cultural ties with the metropole. -

Constructing Dakar: Cultural Theory and Colonial Power Relations in French African Urban Development

CONSTRUCTING DAKAR: CULTURAL THEORY AND COLONIAL POWER RELATIONS IN FRENCH AFRICAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT by Dustin Alan Harris B.A. Honours History, University of British Columbia, 2008 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department Of History © Dustin Alan Harris 2011 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Dustin Alan Harris Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Constructing Dakar: Cultural Theory and Colonial Power Relations in French African Urban Development Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Mary-Ellen Kelm Associate Professor, Department of History Simon Fraser University ___________________________________________ Dr. Roxanne Panchasi Senior Supervisor Associate Professor, Department of History Simon Fraser University ___________________________________________ Dr. Nicolas Kenny Supervisor Assistant Professor, Department of History Simon Fraser University ___________________________________________ Dr. Hazel Hahn External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of History Seattle University Date Defended/Approved: January 26 2011 Note (Don’t forget to delete this note before printing): The Approval page must be only one page long. This is because it MUST be page “ii”, while the Abstract page MUST begin on page “iii”. To accommodate longer titles, longer examining committee lists, or any other feature that demands more space, you have a variety of choices. Consider reducing the font size (10 pt is acceptable), changing the font (see templates Appendix 2, for font choices), using a table to create two columns for examiners, reducing spacing for signatures, indentation and tab spacing. -

3193-Savash Ve Dunya-Askeri Guc Ve Dunyanin Kadri-1450-2000-Jeremy Black

Sava§ ve Dünya AskeriGüç ve KıtalannKaderi 14 50,2000 Jeremy Black (1955) İngiliz sava§ tarihçisi. Exeter Üniversitesi'nde profesör olmasının yanı sıra Dı§ Politika Ara§tırma Enstitüsü'nde de sava§ tarihi üzerine dersler vermektedir. Cambridge'teki Queen's College'te eğitim gördükten sonra akademik kariyerine St. John's, Merton ve Durham üniversitelerinde devam etti. Kanada, Avustralya, Almanya, Fransa, Danimarka gibi ülkelerde konuk öğretim üyesi olarak bulundu. 1996 yılından bu yana Exeter Üniversitesi'nde profesör olarak ders vermektedir. Ba§lıca yapıtları arasında World War Two: A Military History (2003), Retitinking Military History (2004), ve Kings, Nobles and Comrrwners: States and Societies in Early Modem Europe (2004) sayılabilir. D Black, Jeremy Savaş ve Dünya: Askeri Güç ve Kıtaların Kaderi 1450-2000 ISBN 978-975-298-388-5 1 Türkçesi: Yeliz Özkan 1 Dost Kitabevi Yayınları Mart 2009,.Ankara, 504 sayfa. Tarih-Sovo§ Tarihi-Toplumbilim-Notlar-isim Dizini SAVAŞ VE DÜNYA AskeriGüç ve KıtalannKaderi 14 50� 2000 . Jeremy Black ISBN 978-975-298-388-5 War and the World: Miliıary Power and the Faıe of Conıinenıs JEREMY BLACK ©Jeremy Black, 1998 Bu kitabın Türkçe yayın hakları Akcalı Telif Ajansı aracılığıyla Dost Kitabevi Yayınları'na aittir. Birinci Baskı, Mart 2009, Ankara İngilizceden çeviren, Yeliz Özkan Teknik Hazırlık, Mehmet Dirican-Dost İTB Baskıve cilı, PelinOfset Ltd. Şti.; İvedikOrganize Sanayi Bölgesi,Maıbaacılar Sitesi 58 8. SokakNo: 28-30, Yenimalıalle Arıkara 1 Tel:(0312) 3952580-81 • Fax:(0312) 3952584 Dost Kitabevi Yayınlan -

Mauritania Country Study

area handbook series Mauritania country study Mauritania a country study Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Robert E. Handloff Research Completed December 1987 On the cover: Pastoralists near 'Ayoun el 'Atrous Second Edition, First Printing, 1990. Copyright ®1990 United States Government as represented by the Secretary of the Army. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mauritania: A Country Study. Area handbook series, DA pam 550-161 "Research completed June 1988." Bibliography: pp. 189-200. Includes index. Supt. of Docs. no. : D 101.22:000-000/987 1. Mauritania I. Handloff, Robert Earl, 1942- . II. Curran, Brian Dean. Mauritania, a country study. III. Library of Congress. Federal Research Division. IV. Series. V. Series: Area handbook series. DT554.22.M385 1990 966.1—dc20 89-600361 CIP Headquarters, Department of the Army DA Pam 550-161 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This volume is one in a continuing series of books now being prepared by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Con- gress under the Country Studies—Area Handbook Program. The last page of this book lists the other published studies. Most books in the series deal with a particular foreign country, describing and analyzing its political, economic, social, and national security systems and institutions, and examining the interrelation- ships of those systems and the ways they are shaped by cultural factors. Each study is written by a multidisciplinary team of social scientists. The authors seek to provide a basic understanding of the observed society, striving for a dynamic rather than a static portrayal. -

3D Modelization and the Industrial Heritage

3D modelization and the industrial heritage Dr. Jean-Louis Kerouanton (assistant-professor), Université de Nantes, Centre François Viète, Epistémologie Histoire des sciences et des techniques, France Dr. Eng, Florent Laroche (assistant-professor), Ecole Centrale de Nantes, Laboratoire des sciences du numérique, France 3D modelization is very well known today in industry and engineering but also in games. Its applications for culture and human sciences are more recent. However, the development of such applications today is quite important in archaeology with amazing results. The proposal of this communication is to show how 3D modelling, and more generally data knowledge, provides new perspectives for approaching industrial archaeology, between knowledge, conservation and valorisation, especially in museums. A new way for us to imagine contemporary archaeology: by the way not only new methodology but actually archaeology of contemporary objects. That is we are trying in Nantes associated laboratories (Université de Nantes, Ecole centrale de Nantes) in stretch collaborations with museums. This double point of view succeeds necessarily with interdisciplinary questioning between engineering and human sciences approaches for the development of digital humanities. We are trying today to enhance and develop our interdisciplinary methodology for heritage and museology in a new ANR resarch project, RESEEDi1. Interdisciplinarity for valorization “When heritage becomes virtual” Over the past 10 years, our research collaboration has focused on industrial heritage. It is an interdisciplinary approach between the Centre François Viète2, a laboratory of history of science and technology from University of Nantes3, and the LS2N4, Laboratoire des sciences du numérique de Nantes, a mixt Research unity between CNRS , the University of Nantes and the Ecole Centrale de Nantes, and more precisely inside LS2N, the ex IRCCyN, a cybernetics laboratory from Centrale Nantes5.