Language, Identity, and Power in Mauritania Under French Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Evaluation and Assessment of Meteorological Drought by Different Methods in Trarza Region, Mauritania

Water Resour Manage (2017) 31:825–845 DOI 10.1007/s11269-016-1510-8 Evaluation and Assessment of Meteorological Drought by Different Methods in Trarza Region, Mauritania Ely Yacoub1 & Gokmen Tayfur1 Received: 6 June 2016 /Accepted: 20 September 2016 / Published online: 10 October 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 Abstract Drought Indexes (DIs) are commonly used for assessing the effect of drought such as the duration and severity. In this study, long term precipitation records (monthly recorded for 44 years) in three stations (Boutilimit (station 1), Nouakchott (station 2), and Rosso (station 3)) are employed to investigate the drought characteristics in Trarza region in Mauritania. Six DI methods, namely normal Standardized Precipitation Index (normal-SPI), log normal Standardized Precipitation Index (log-SPI), Standardized Precipitation Index using Gamma distribution (Gamma-SPI), Percent of Normal (PN), the China-Z index (CZI), and Deciles are used for this purpose. The DI methods are based on 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12 month time periods. The results showed that DIs produce almost the same results for the Trarza region. The droughts are detected in the seventies and eighties more than the 1990s. Twelve drought years might be experienced in station 2 and six in stations 1 and 3 in every 44 years, according to reoccurrence probability of the gamma-SPI and log-SPI results. Stations 1 and 3 might experience fewer drought years than station 2, which is located right on the coast. In station 1, which is located inland, when the annual rainfall is less than 123 mm, it is likely that severe drought would occur. -

Ghana), 1922-1974

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN EWEDOME, BRITISH TRUST TERRITORY OF TOGOLAND (GHANA), 1922-1974 BY WILSON KWAME YAYOH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APRIL 2010 ProQuest Number: 11010523 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010523 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for Students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE S O A S lTb r a r y ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of local government in the Ewedome region of present-day Ghana and explores the transition from the Native Authority system to a ‘modem’ system of local government within the context of colonization and decolonization. -

Report Summary: Privatisation, Commercialisation, and Sale of Public Schools in Mauritania This Is a Summary of the Full Report Available Here

Association des Coalition des Organisations Femmes Chefs Mauritaniennes pour de Familles l’Education Report Summary: Privatisation, commercialisation, and sale of public schools in Mauritania This is a summary of the full report available here The Mauritanian education system rapidly privatised over the last 20 years, following the authorisation and promotion of private education by the Government, and because of the lack of regulation and supervision of private actors in education. This de facto privatisation has been accompanied by an increasing commercialisation of education through, the auctioning of public- school grounds since 2015 to transform them into commercial premises. 1. Private schools are progressing rapidly in the Mauritanian education system The share of students in the private education sector has increased more than eightfold in only 16 years. A phenomenon of this magnitude necessarily requires special attention and support to ensure that it does not undermine the right to education. 2. The growth of private actors in the Mauritanian education system contributes to creating divides according to household income Only the most affluent people in Mauritania (20%), who are able to spend four times more on primary education than the poorest families (40%), can enrol their children in private schools of good quality. Even in the case of the so-called "low cost" schools, with tuition fees promoted as low, these remain an obstacle to access to these schools for many families. These registration fees can be a major reason of de-schooling for families unable to pay them. 1 Association des Coalition des Organisations Femmes Chefs Mauritaniennes pour de Familles l’Education 3. -

North Africa, South Africa

North Africa POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS International Relations T -LHE YEAR was marked by greater rapprochement among the coun- tries of North Africa. Old disputes were settled or were on the way to settle- ment, and agreements for cooperation were developed. There was also a general improvement in relations between the countries of North Africa and nations outside the immediate area. However, there was increased anti-Israel activity, primarily on the diplomatic and public-relations fronts. A development of potential importance, but one whose effects could not yet be assessed fully, was the overthrow in September of King Idris of Libya by a group of young officers under strong Egyptian influence. Treaties of solidarity and cooperation were signed between Tunisia and Morocco, in January, and between Algeria and Libya, in February. When President Houari Boumedienne of Algeria visited King Hassan of Morocco to draw up the document, Hassan used the occasion to emphasize the im- portance of unity and regional agreements for the development of the Arab countries and the preservation of their freedom against outside aggression, particularly by Israel. Negotiations for a similar treaty between Algeria and Tunisia began in January, a year behind schedule, but there were difficulties because Tunisia gave asylum to Algerian political refugees and because the Tunisian press charged that there were Soviet bases in Algeria. Not until December was there an announcement that complete agreement had been reached on "all pending questions," apparently including disagreements on the delineation of the frontier. A number of international conferences took place in Algeria and Morocco in 1969. The annual conference of African ministers of labor, meeting in Algiers in March, called for a boycott of cargoes coming from South Africa, Portugal, and Israel, a demand which, however, failed to win the support of several countries from other parts of the continent. -

Migrations Internationales Ouest Africaines Et Les Trajectoires

Ba Cheikh Oumar. (1992) Migrations internationales ouest africaines et les trajectoires migratoires dans la vallée du fleuve Sénégal : étude menée à partir de deux villages à dominante ethnique : Halpulaar (Galoya) et Soninké (Bokidiawé) : rapport de stage Dakar : ORSTOM, 35 p. multigr. RAPPORT DE FIN DE STAGE A L'ORSTOM SOUS LA DIRECTION DE SYLVIE BREDELOUP, CHERCHEUR A L'ORSTOM Du 30 avril au 30 juillet soit pendant trois mois, nous avons eu à. effectuer, sous la .direction de Sylvie Bredeloup, un stage à. l 'ORSTOM. Ce stage entrait dans l'orientation de nos recherches pour le DEA à l'université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar. C'est ainsi que nous avons été recommandé par notre directeur de recherche le Pro Abdoulaye Bara Diop à Sylvie Bredeloup chercheur à. l'ORSTOM dans le cadre du programme "migrations internationales Ouest-africaines" initié au sein du' département sud de l'ORSTOM. Dans ~e cadre nous avons été emmené à effectuer deux missions .d"un mois chacune dans les villages de Galoya (Torodo et Peulh) et Bokidiawé (Soninké et halpulaar) • Ces missions ont bénéficié de l'aide· matérielle de l'ORSTOM et morale- de nos -'deux responsables de recherche précédemment cités. De part; . leur conseil méthodologique" ils ont rendu ce stage possible d "amont en aval. Qu'ils trouvent ici nos remerciements, eux sans qui ce travail ne serait même pas envisageable compte tenu des conditions sociales dans lesquelles nous nous trouvions avant d'e~~er ce travail. Nous tenons à. remercier tous les chercheurs de l'ORSTOM qui nous ont apporté chaque fois que nous leur avons sollicité leur aide très appréciable, ainsi qu'à. -

The Economic Foundations of Authoritarian Rule

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 The conomicE Foundations of Authoritarian Rule Clay Robert Fuller University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fuller, C. R.(2017). The Economic Foundations of Authoritarian Rule. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4202 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECONOMIC FOUNDATIONS OF AUTHORITARIAN RULE by Clay Robert Fuller Bachelor of Arts West Virginia State University, 2008 Master of Arts Texas State University, 2010 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2014 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: John Hsieh, Major Professor Harvey Starr, Committee Member Timothy Peterson, Committee Member Gerald McDermott, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright Clay Robert Fuller, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION for Henry, Shannon, Mom & Dad iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks goes to God, the unconditional love and support of my wife, parents and extended family, my dissertation committee, Alex, the institutions of the United States of America, the State of South Carolina, the University of South Carolina, the Department of Political Science faculty and staff, the Walker Institute of International and Area Studies faculty and staff, the Center for Teaching Excellence, undergraduate political science majors at South Carolina who helped along the way, and the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. -

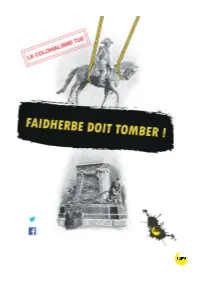

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Looters Vs. Traitors: the Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and Its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire

Looters vs. Traitors: The Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire Abstract: Since 2012, when broadcasting licenses were granted to various private television and radio stations in Mauritania, the controversy around the Battle of Um Tounsi (and Mauritania’s colonial past more generally) has grown substantially. One of the results of this unprecedented level of media freedom has been the prop- agation of views defending the Mauritanian resistance (muqawama in Arabic) to French colonization. On the one hand, verbal and written accounts have emerged which paint certain groups and actors as French colonial power sympathizers. At the same time, various online publications have responded by seriously questioning the very existence of a structured resistance to colonization. This article, drawing pre- dominantly on local sources, highlights the importance of this controversy in study- ing the western Saharan region social model and its contemporary uses. African Studies Review, Volume 63, Number 2 (June 2020), pp. 258– 280 Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba is Professor of History and Sociolinguistics at the University of Nouakchott, Mauritania (Ph.D. University of Provence (Aix- Marseille I); Fulbright Scholar resident at Northwestern University 2012–2013), and a Senior Research Consultant at the CAPSAHARA project (ERC-2016- StG-716467). E-mail: [email protected] Francisco Freire is an Anthropologist (Ph.D. Universidade Nova de Lisboa 2009) at CRIA–NOVA FCSH (Lisbon, Portugal). He is the Principal Investigator of the European Research Council funded project CAPSAHARA: Critical Approaches to Politics, Social Activism and Islamic Militancy in the Western Saharan Region (ERC-2016-StG-716467). -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N

!ho o Õ o !ho !h h !o ! o! o 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 0°0'0" Laayoune / El Aaiun HASSAN I LAAYOUNE !h.!(!o SMARAÕ !(Smara !o ! Cabo Bu Craa Algeria Bojador!( o Western Sahara BIR MOGHREIN 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Ad Dakhla h (!o DAKHLA Tiris Zemmour DAJLA !(! ZOUERAT o o!( FDERIK AIRPORT Zouerate ! Bir Gandus o Nouadhibou NOUADHIBOU (!!o Adrar ! ( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa !h NOUADHIBOU ! Atar (!o ! ATAR Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N AKJOUJT o ! ATLANTIC OCEAN Akjoujt Tagant TIDJIKJA ! o o o Tidjikja TICHITT Nouakchott Nouakchott Hodh Ech Chargui (!o NOUAKCHOTT Nbeika !h.! Trarza ! ! NOUAKCHOTT MOUDJERIA o Moudjeria o !Boutilimit BOUTILIMIT ! Magta` Lahjar o Mal ! TAMCHAKETT Aleg! ! Brakna AIOUN EL ATROUSS !Guerou Bourem PODOR AIRPORTo NEMA Tombouctou! o ABBAYE 'Ayoun el 'Atrous TOMBOUCTOU Kiffa o! (!o o Rosso ! !( !( ! !( o Assaba o KIFFA Nema !( Tekane Bogue Bababe o ! o Goundam! ! Timbedgha Gao Richard-Toll RICHARD TOLL KAEDI o ! Tintane ! DAHARA GOUNDAM !( SAINT LOUIS o!( Lekseiba Hodh El Gharbi TIMBEDRA (!o Mbout o !( Gorgol ! NIAFUNKE o Kaedi ! Kankossa Bassikounou KOROGOUSSOU Saint-Louis o Bou Gadoum !( ! o Guidimaka !( !Hamoud BASSIKOUNOU ! Bousteile! Louga OURO SOGUI AIRPORT o ! DODJI o Maghama Ould !( Kersani ! Yenje ! o 'Adel Bagrou Tanal o !o NIORO DU SAHEL SELIBABY YELIMANE ! NARA Niminiama! o! o ! Nioro 15°0'0"N Nara ! 15°0'0"N Selibabi Diadji ! DOUTENZA LEOPOLD SEDAR SENGHOR INTL Thies Touba Senegal Gouraye! du Sahel Sandigui (! Douentza Burkina (! !( o ! (!o !( Mbake Sandare! -

Crime, Punishment, and Colonization: a History of the Prison of Saint-Louis and the Development of the Penitentiary System in Senegal, Ca

CRIME, PUNISHMENT, AND COLONIZATION: A HISTORY OF THE PRISON OF SAINT-LOUIS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PENITENTIARY SYSTEM IN SENEGAL, CA. 1830-CA. 1940 By Ibra Sene A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY HISTORY 2010 ABSTRACT CRIME, PUNISHMENT, AND COLONIZATION: A HISTORY OF THE PRISON OF SAINT-LOUIS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PENITENTIARY SYSTEM IN SENEGAL, CA. 1830-CA. 1940 By Ibra Sene My thesis explores the relationships between the prison of Saint-Louis (Senegal), the development of the penitentiary institution, and colonization in Senegal, between ca. 1830 and ca. 1940 . Beyond the institutional frame, I focus on how the colonial society influenced the implementation of, and the mission assigned to, imprisonment. Conversely, I explore the extent to which the situation in the prison impacted the relationships between the colonizers and the colonized populations. First, I look at the evolution of the Prison of Saint-Louis by focusing on the preoccupations of the colonial authorities and the legislation that helped implement the establishment and organize its operation. I examine the facilities in comparison with the other prisons in the colony. Second, I analyze the internal operation of the prison in relation to the French colonial agenda and policies. Third and lastly, I focus on the ‘prison society’. I look at the contentions, negotiations and accommodations that occurred within the carceral space, between the colonizer and the colonized people. I show that imprisonment played an important role in French colonization in Senegal, and that the prison of Saint-Louis was not just a model for, but also the nodal center of, the development of the penitentiary. -

2. Arrêté N°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ Du 24 Août 2006 Fixant Le Nombre De Conseillers Au Niveau De Chaque Commune

2. Arrêté n°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ du 24 août 2006 fixant le nombre de conseillers au niveau de chaque commune Article Premier: Le nombre de conseillers municipaux des deux cent seize (216) Communes de Mauritanie est fixé conformément aux indications du tableau en annexe. Article 2 : Sont abrogées toutes dispositions antérieures contraires, notamment celles relatives à l’arrêté n° 1011 du 06 Septembre 1990 fixant le nombre des conseillers des communes. Article 3 : Les Walis et les Hakems sont chargés, chacun en ce qui le concerne, de l’exécution du présent arrêté qui sera publié au Journal Officiel. Annexe N° dénomination nombre de conseillers H.Chargui 101 Nema 10101 Nema 19 10102 Achemim 15 10103 Jreif 15 10104 Bangou 17 10105 Hassi Atile 17 10106 Oum Avnadech 19 10107 Mabrouk 15 10108 Beribavat 15 10109 Noual 11 10110 Agoueinit 17 102 Amourj 10201 Amourj 17 10202 Adel Bagrou 21 10203 Bougadoum 21 103 Bassiknou 10301 Bassiknou 17 10302 El Megve 17 10303 Fassala - Nere 19 10304 Dhar 17 104 Djigueni 10401 Djiguenni 19 10402 MBROUK 2 17 10403 Feireni 17 10404 Beneamane 15 10405 Aoueinat Zbel 17 10406 Ghlig Ehel Boye 15 Recueil des Textes 2017/DGCT avec l’appui de la Coopération française 81 10407 Ksar El Barka 17 105 Timbedra 10501 Timbedra 19 10502 Twil 19 10503 Koumbi Saleh 17 10504 Bousteila 19 10505 Hassi M'Hadi 19 106 Oualata 10601 Oualata 19 2 H.Gharbi 201 Aioun 20101 Aioun 19 20102 Oum Lahyadh 17 20103 Doueirare 17 20104 Ten Hemad 11 20105 N'saveni 17 20106 Beneamane 15 20107 Egjert 17 202 Tamchekett 20201 Tamchekett 11 20202 Radhi