Conquering Autonomy in the Administration: French Colonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif

“Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani To cite this version: Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani. “Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif.. Comparativ, Leipzig University, 2019, 29 (3), pp.41-64. hal-02954571 HAL Id: hal-02954571 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954571 Submitted on 1 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo, 1890-1914. Debates about abolition of slavery have essentially focused on two interrelated questions: 1) whether nineteenth and early twentieth century abolitions were a major breakthrough compared to previous centuries (or even millennia) in the history of humankind during which bondage had been the dominant form of labour and human condition. 2) whether they express an action specific to western bourgeoisie and liberal civilization. It is true that the number of abolitionist acts and the people concerned throughout the extended nineteenth century (1780- 1914) had no equivalent in history: 30 million Russian peasants, half a million slaves in Saint- Domingue in 1790, four million slaves in the US in 1860, another million in the Caribbean (at the moment of the abolition of 1832-40), a further million in Brazil in 1885 and 250,000 in the Spanish colonies were freed during this period. -

Indochina 1900-1939"

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/35581 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. "French Colonial Discourses: the Case of French Indochina 1900-1939". Nicola J. Cooper Thesis submitted for the Qualification of Ph.D. University of Warwick. French Department. September 1997. Summary This thesis focuses upon French colonial discourses at the height of the French imperial encounter with Indochina: 1900-1939. It examines the way in which imperial France viewed her role in Indochina, and the representations and perceptions of Indochina which were produced and disseminated in a variety of cultural media emanating from the metropole. Framed by political, ideological and historical developments and debates, each chapter develops a socio-cultural account of France's own understanding of her role in Indochina, and her relationship with the colony during this crucial period. The thesis asserts that although consistent, French discourses of Empire do not present a coherent view of the nation's imperial identity or role, and that this lack of coherence is epitomised by the Franco-indochinese relationship. The thesis seeks to demonstrate that French perceptions of Indochina were marked above all by a striking ambivalence, and that the metropole's view of the status of Indochina within the Empire was often contradictory, and at times paradoxical. -

Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy Towards Africa: Pragmatism Or Altruism Abdurrahim Sıradağ1

Afro Eurasian Studies Journal Vol 3. Issue 1, Spring 2014 Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy towards Africa: Pragmatism or Altruism Abdurrahim Sıradağ1 Abstract France has deep economic, political and historical relations with Africa, dating back to the 17th century. Since the independence of the former colonial countries in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, France has continued to maintain its economic and political relations with its former colonies. Importantly, France has a special strategic security partnership with the African countries. It has intervened militarily in Africa more than 50 times since 1960. France has especially continued to use its military power to strengthen its economic, political and strategic relations with Africa. For instance, it deployed its military troops in Mali in January 2013 and in the Central African Republic in December 2013. Why does France actively get involved in Africa militarily? This research will particularly uncover the main motivations behind the French foreign and security policy in Africa. Key words: Francophone Africa, France, Foreign Policy, Africa, economic interests. The Role of France in World Politics France’s international power and position has shaped its foreign and security policy towards Africa. France has been an important actor with its political and economic power in Europe and in the world. It was one of the six important founding members of the European Community after 1 International University of Sarajevo, Department of International Relations, Ilidža, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Email: [email protected] 100 the Second World War and plays a leading role in European integration. France plays a significant role in world politics through international or- ganizations. -

8.. Colonialism in the Horn of Africa

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The state, the crisis of state institutions and refugee migration in the Horn of Africa : the cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia Degu, W.A. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Degu, W. A. (2002). The state, the crisis of state institutions and refugee migration in the Horn of Africa : the cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia. Thela Thesis. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 8.. COLONIALISM IN THE HORN OF AFRICA 'Perhapss there is no other continent in the world where colonialism showed its face in suchh a cruel and brutal form as it did in Africa. Under colonialism the people of Africa sufferedd immensely. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Understanding African Armies

REPORT Nº 27 — April 2016 Understanding African armies RAPPORTEURS David Chuter Florence Gaub WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Taynja Abdel Baghy, Aline Leboeuf, José Luengo-Cabrera, Jérôme Spinoza Reports European Union Institute for Security Studies EU Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print ISBN 978-92-9198-482-4 ISSN 1830-9747 doi:10.2815/97283 QN-AF-16-003-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9198-483-1 ISSN 2363-264X doi:10.2815/088701 QN-AF-16-003-EN-N Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in France by Jouve. Graphic design by Metropolis, Lisbon. Maps: Léonie Schlosser; António Dias (Metropolis). Cover photograph: Kenyan army soldier Nicholas Munyanya. Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/SIPA CONTENTS Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli I. Introduction: history and origins 9 II. The business of war: capacities and conflicts 15 III. The business of politics: coups and people 25 IV. Current and future challenges 37 V. Food for thought 41 Annexes 45 Tables 46 List of references 65 Abbreviations 69 Notes on the contributors 71 ISSReportNo.27 List of maps Figure 1: Peace missions in Africa 8 Figure 2: Independence of African States 11 Figure 3: Overview of countries and their armed forces 14 Figure 4: A history of external influences in Africa 17 Figure 5: Armed conflicts involving African armies 20 Figure 6: Global peace index 22 Figure -

British Columbia 1858

Legislative Library of British Columbia Background Paper 2007: 02 / May 2007 British Columbia 1858 Nearly 150 years ago, the land that would become the province of British Columbia was transformed. The year – 1858 – saw the creation of a new colony and the sparking of a gold rush that dramatically increased the local population. Some of the future province’s most famous and notorious early citizens arrived during that year. As historian Jean Barman wrote: in 1858, “the status quo was irrevocably shattered.” Prepared by Emily Yearwood-Lee Reference Librarian Legislative Library of British Columbia LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BACKGROUND PAPERS AND BRIEFS ABOUT THE PAPERS Staff of the Legislative Library prepare background papers and briefs on aspects of provincial history and public policy. All papers can be viewed on the library’s website at http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/ SOURCES All sources cited in the papers are part of the library collection or available on the Internet. The Legislative Library’s collection includes an estimated 300,000 print items, including a large number of BC government documents dating from colonial times to the present. The library also downloads current online BC government documents to its catalogue. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the Legislative Library or the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. While great care is taken to ensure these papers are accurate and balanced, the Legislative Library is not responsible for errors or omissions. Papers are written using information publicly available at the time of production and the Library cannot take responsibility for the absolute accuracy of those sources. -

UK and Colonies

This document was archived on 27 July 2017 UK and Colonies 1. General 1.1 Before 1 January 1949, the principal form of nationality was British subject status, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the Crown's dominions. On and after this date, the main form of nationality was citizenship of the UK and Colonies, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the UK and Colonies. 2. Meaning of the expression 2.1 On 1 January 1949, all the territories within the Crown's dominions came within the UK and Colonies except for the Dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, India, Pakistan and Ceylon (see "DOMINIONS") and Southern Rhodesia, which were identified by s.1(3) of the BNA 1948 as independent Commonwealth countries. Section 32(1) of the 1948 Act defined "colony" as excluding any such country. Also excluded from the UK and Colonies was Southern Ireland, although it was not an independent Commonwealth country. 2.2 For the purposes of the BNA 1948, the UK included Northern Ireland and, as of 10 February 1972, the Island of Rockall, but excluded the Channel Islands and Isle of Man which, under s.32(1), were colonies. 2.3 The significance of a territory which came within the UK and Colonies was, of course, that by virtue of a connection with such a territory a person could become a CUKC. Persons who, prior to 1 January 1949, had become British subjects by birth, naturalisation, annexation or descent as a result of a connection with a territory which, on that date, came within the UK and Colonies were automatically re- classified as CUKCs (s.12(1)-(2)). -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

A Cape of Asia: Essays on European History

A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 1 a cape of asia A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 2 A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 3 A Cape of Asia essays on european history Henk Wesseling leiden university press A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 4 Cover design and lay-out: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie, Amsterdam isbn 978 90 8728 128 1 e-isbn 978 94 0060 0461 nur 680 / 686 © H. Wesseling / Leiden University Press, 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 5 Europe is a small cape of Asia paul valéry A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 6 For Arnold Burgen A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 7 Contents Preface and Introduction 9 europe and the wider world Globalization: A Historical Perspective 17 Rich and Poor: Early and Later 23 The Expansion of Europe and the Development of Science and Technology 28 Imperialism 35 Changing Views on Empire and Imperialism 46 Some Reflections on the History of the Partition -

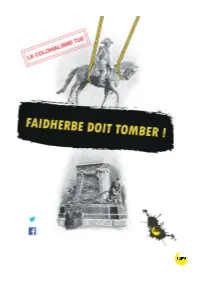

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang.