Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

DIASPORA and IDENTITY in the SELECTED POEMS of MEENA ALEXANDER Pooja Kushwaha Research Scholar Department of English and M.E.L

International Journal of Engineering Applied Sciences and Technology, 2020 Vol. 5, Issue 5, ISSN No. 2455-2143, Pages 100-104 Published Online September 2020 in IJEAST (http://www.ijeast.com) DIASPORA AND IDENTITY IN THE SELECTED POEMS OF MEENA ALEXANDER Pooja Kushwaha Research Scholar Department of English and M.E.L. University of Lucknow, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. Abstract- On the literary map of Indian women writings, The new poetry has emerged as a new awareness. Modern Meena Alexander appears to be leading woman poetess. Indian poetry finds one of its authentic voices in English. It The question of identity is the most controversial issue in is enriched by the experiences of Diaspora writers. It postcolonial time and literature and it can be regarded the represents the complexity of Indian experience poetry. The most important because its crisis exists in all postcolonial women poets of Indian Diaspora have migrated to and settled communities. She negotiates with the issue of ‘Diaspora’ in various countries like USA, Australia, Denmark, England and ‘Identity’ in almost all her writings. Meena and Germany. They are living in foreign country. The Alexander is always in an experiment on the issues of contribution of contemporary Indian women poets in English ‘Diaspora’ and ‘Identity’ in her creative oeuvre. This represent the range of their talent. The contemporary women paper endeavors to explore her postcolonial journey and poets show the Indian womanhood and emphasize on the her views of making a home, a living one and a literary search of identity. The new poets carry wounds in their one, and an individual identity of her own through her hearts. -

Profile/ Curriculum Vitae

BANKURA UNIVERSITY FACULTY ACADEMIC PROFILE/ CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Name: Dr. SUBHADEEP PAUL 2. Designation: ASSISTANT PROFESSOR 3. Date of Birth : 15/10/1980 4. Specializations: Postcolonial & New Literatures, Multiculturalism and multicultural literature, Indian Writing in English, American Literature, Diaspora Studies, Cultural Representations of Hollywood, Cultural and Literary Gerontology, Literature and Trauma, Literature of the Border, Posthumanism and critical appropriations of Futurism. 5. Contact Information: Contact Address: P19 Raipur. Flat A1. P.O. Garia. Kolkata – 700084. W.B., India. Email: [email protected] 6. Academic qualifications: College/ University from which the Abbreviation of the degree degree was obtained St. Xavier’s College, University of B.A. Calcutta Jadavpur University M.A. Jadavpur University M. Phil Jadavpur University Ph. D 7. Past Employments/ Academic Experience: Assistant Professor in English, Maulana Azad College, Kolkata, West Bengal Educational Service (W.B.E.S.) from 2009 to 2015. 8. Research Interests: Studies of the Orient and the Occident Cultural Theory Scottish Studies Critical Reflections on Popular Culture 21st Century Shakespeare Studies Ethics Creative Writing (Fiction and Poetry) Page 1 of 6 9. Research Guidance / Supervision: Number of researchers pursuing M.Phil. / Ph.D.: 02 10. Research Projects: Current projects: Co-Director of ongoing ICSSR Two Year Major Research Project entitled “Discoursing the Homeless Elderly: Tropes, Desires, Containment” (In Collaboration with The University of Swansea, UK), 2016-2018 [Awaiting Award]. Research Guidance: 1. Smt. Nabanita Karanjai (Ph. D Candidate) – “The Ontology of the Human Subject in the Digital Age: A Posthumanist Analysis of Select Literary Works” (ongoing). 2. Shri. Abhishek Das (Ph. D Candidate) – “Representation of Muslims in Select Pakistani Diasporic Fiction: A Critical Study” (ongoing). -

Self Study Report

Self Study Report Submitted To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL Bangalore-560072 By Arya Vidyapeeth College (Affiliated to Gauhati University, Guwahati) Gopinath Nagar Guwahati-781016 ASSAM Office of the Principal ARYA VIDYAPEETH COLLEGE: GUWAHATI-781016 Ref. No. AVC/Cert./2015/ Dated Guwahati the 25/12/2015 Certificate of Compliance (Affiliated/Constitutent/Autonomous Colleges and Recognized Institute) This is to certify that Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati-16, fulfills all norms: 1. Stipulated by the affiliating University and/or 2. Regulatory council/Body [such as UGC, NCTE, AICTE, MCI, DCI, BCI, etc.] and 3. The affiliation and recognition [if applicable] is valid as on date. In case the affiliation/recognition is conditional, then a detailed enclosure with regard to compliance of conditions by the institution will be sent. It is noted that NAAC’s accreditation, if granted, shall stand cancelled automatically, once the institution loses its university affiliation or recognition by the regulatory council, as the case may be. In case the undertaking submitted by the institution is found to be false then the accreditation given by the NAAC is liable to be withdrawn. It is also agreeable that the undertaking given to NAAC will be displayed on the college website. Place: Guwahati (Harekrishna Deva Sarmah) Date: 25-12-2015 Principal Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati-16 Self Study Report Arya Vidyapeeth College Page 2 Office of the Principal ARYA VIDYAPEETH COLLEGE: GUWAHATI-781016 Ref. No. AVC/Cert./2015/ Dated Guwahati the 25/12/2015 DECLARATION This is to certify that the data included in this Self Study Report (SSR) is true to the best of my knowledge. -

Literature of Review: Introduction: India Is the Land of Beauty And

Literature of Review: Introduction: India is the land of beauty and diversity. There exist number of poetic forms, styles and methods. Many poets from india are bilingual who carried the treasures from Indian languages to Europeans and English literature to Indian readers. The present work aims at critically analyzing Arun Kolatkar’s Jejuri. Thus it becomes a matter of immense importance to study and take review of Indian poetry written in English to locate Arun Kolatkar in the poetry tradition. Meaning of Indo-English Poetry: According to Oxford Dictonary Indo is the combination form (especially in linguistic and ethological forms) Indian. Indo- English poetry is the poems written by Indian poets in English. It is believed that the English literature began as an intresting by-product of an eventful encounter in the late 18th century between Britain and India. It has been known by different term such as ‘Indo-Anglican literature’, ‘Indian writing in English ‘ and ‘Indo- English literature .However , the Indian English literarture is defined as literature written originally in English by authors Indian by birth,ancestry or nationality. This literature is legitimately a part of Indian literature, since its differntia is the expression in it of an Indian ethos .The poetry written in English in india is classified differently by different scholars; however , it is mainly classified as Early poetry , Poetry written during Gandhian Age, Poetry after Independence. Early Poetry: The first Indian English poet who is considered seriously is Henry Louis Vivian Derozio(1809-31). He was the son of an Indo-Portuguese father and an English mother. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies MZU JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURAL STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Volume IV Issue 1 ISSN:2348-1188 Editor : Dr. Cherrie Lalnunziri Chhangte Editorial Board: Prof. Margaret Ch.Zama Prof. Sarangadhar Baral Prof. Margaret L.Pachuau Dr. Lalrindiki T. Fanai Dr. K.C. Lalthlamuani Dr. Kristina Z. Zama Dr. Th. Dhanajit Singh Advisory Board: Prof. Jharna Sanyal, University of Calcutta Prof. Ranjit Devgoswami,Gauhati University Prof. Desmond Kharmawphlang, NEHU Shillong Prof. B.K. Danta, Tezpur University Prof. R. Thangvunga, Mizoram University Prof. R.L. Thanmawia, Mizoram University Published by the Department of English, Mizoram University. 1 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies 2 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies FOREWORD The present issue of MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies has encapsulated the eclectic concept of culture and its dynamics, especially while pertaining to the enigma that it so often strives to be. The complexities within varying paradigms, that seek to determine the significance of ideologies and the hegemony that is often associated with the same, convey truly that the old must seek to coexist, in more ways than one with the new. The contentions, keenly raised within the pages of the journal seek to establish too, that a dual notion of cultural hybridity that is so often particular to almost every community has sought too, to establish a voice. Voices that may be deemed ‘minority’ undoubtedly, yet expressed in tones that are decidedly -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

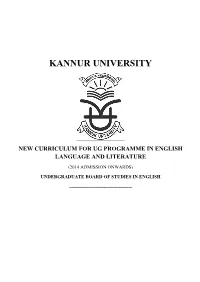

2014-Admn-Syllabus

KANNUR UNIVERSITY NEW CURRICULUM FOR UG PROGRAMME IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (2014 ADMISSION ONWARDS) UNDERGRADUATE BOARD OF STUDIES IN ENGLISH ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 1. Table of Common Courses Sl Sem Course Title of Course Hours/ Credit Marks No: ester Code Week ESE CE Total 1 1 1A01ENG Communicative English I 5 4 40 10 50 2 1 1A02ENG Language Through Literature 1 4 3 40 10 50 3 2 2A03ENG Communicative English II 5 4 40 10 50 4 2 2A04ENG Language Through Literature II 4 3 40 10 50 5 3 3A05ENG Readings in Prose and Poetry 5 4 40 10 50 6 4 4A06ENG Readings in Fiction and Drama 5 4 40 10 50 2. Table of Core Courses Sl Seme Course Title of course Hours/ Credit Marks No: ster code Week ESE CE Total 1 1 1B01ENG History of English Language 6 4 40 10 50 and Literature 2 2 2B02ENG Studies in Prose 6 4 40 10 50 3 3 3B03ENG Linguistics 5 4 40 10 50 4 3 3B04ENG English in the Internet Era 4 4 40 10 50 5 4 4B05ENG Studies in Poetry 4 4 40 10 50 6 4 4B06ENG Literary Criticism 5 5 40 10 50 7 5 5B07ENG Modern Critical Theory 6 5 40 10 50 8 5 5B08ENG Drama: Theory and Literature 6 4 40 10 50 9 5 5B09ENG Studies in Fiction 6 4 40 10 50 10 5 5B10ENG Women‘s Writing 5 4 40 10 50 11 6 6B11ENG Project 1 2 20 5 25 12 6 6B12ENG Malayalam Literature in 5 4 40 10 50 Translation 13 6 6B13ENG New Literatures in English 5 4 40 10 50 14 6 6B14ENG Indian Writing in English 5 4 40 10 50 15 6 6B15ENG Film Studies 5 4 40 10 50 16 6 6B16ENG Elective 01, 02, 03 4 4 40 10 50 3. -

MA English Revised (2016 Admission)

KANNUR Li N I \/EttSIl Y (Abstract) M A Programme in English Language programnre & Lirerature undcr Credit Based semester s!.stem in affiliated colieges Revised pattern Scheme. s,'rabus and of euestion papers -rmplemenred rvith effect from 2016 admission- Orders issued. ACADEMIC C SECTION UO.No.Acad Ci. til4t 20tl Civil Srarion P.O, Dared,l5 -07-20t6. Read : l. U.O.No.Acad/Ct/ u 2. U.C of €ven No dated 20.1O.2074 3. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pc) held on 06_05_2016. 4. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pG) held on 17_06_2016. 5. Letter dated 27.06.201-6 from the Chairman, Board of Studies in English(pc) ORDER I. The Regulations lor p.G programmes under Credit Based Semester Systeln were implernented in the University with eriect from 20r4 admission vide paper read (r) above dated 1203 2014 & certain modifications were effected ro rhe same dated 05.12.2015 & 22.02.2016 respectively. 2. As per paper read (2) above, rhe Scherne Sylrabus patern - & ofquesrion papers rbr 1,r A Programme in English Language and Literature uncler Credir Based Semester System in affiliated Colleges were implcmented in the University u,.e.i 2014 admission. 3. The meeting of the Board of Studies in En8lish(pc) held on 06-05_2016 , as per paper read (3) above, decided to revise the sylrabus programme for M A in Engrish Language and Literature rve'f 2016 admission & as per paper read (4) above the tsoard of Studies finarized and recommended the scheme, sy abus and pattem of question papers ror M A programme in Engrish Language and riterature for imprementation wirh efl'ect from 20r6 admissiorr. -

Art, Violence and Ethnic Identity in Meena Alexander's Manhattan Music

Art, Violence and Ethnic Identity in Meena Alexander’s Manhattan Music 149 Izabella Kimak “A Bridge !at Seizes Crossing”: Art, Violence and Ethnic Identity in Meena Alexander’s Manhattan Music Meena Alexander, an American writer born in India and now living in New York City, in all of her creative work exhibits a sensitivity to the experience of cross- ing borders, which entails the need to form new, hybrid identities and to learn to juggle not only diverse cultures but diverse languages as well. In comparison to other women writers of the South Asian diaspora in the US, such as Bharati Mukherjee and Jhumpa Lahiri, Alexander has been somewhat overlooked by general readers, although her writing has received substantial praise from critics, especially those of Indian provenance. However, scholarly attention so far has mostly been paid to Alexander’s poetry and memoir at the expense of her two !ctional texts: Nampally Road (1991), set in India, and Manhattan Music (1997), oscillating between Kerala and New York. In the latter novel, as well as in her poetry and memoir, Alexander explores the experience of immigration with its ensuing feelings of uprootedness and displacement. In this respect, Alexander’s thematic interests seem to coincide with those of other writers of the South Asian diaspora in the US,1 but this apparent similarity is in fact somewhat misleading. With its carefully cra"ed language and its elaborate structure, Manhattan Music 1 #is fact is stressed by numerous scholars who have attempted to characterize South Asian American literature as a unique body of writing ever since “Indians, whether as South Asians or as diasporic Indians, acquired a distinct literary identity” (Gurleen Grewal 91) in the 1990s. -

Representation of Caste Issue in Mainstream Literature and Regional Literature

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.5.Issue 4. 2017 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (Oct-Dec) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE REPRESENTATION OF CASTE ISSUE IN MAINSTREAM LITERATURE AND REGIONAL LITERATURE P. REVATHI Research Scholar, Assistant Professor, Department of English Vel Tech Technical Univeristy, Avadi, Chennai-62, Tamil Nadu, India. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The major focus of this piece of writing is to compare the way of representation of caste as theme for two prominent schools of writing in India; that is Indian Literature in English and Indian Literature in other languages. David Davidar and Omprakash Valmiki’s work are chosen for the article. Among their works The House of Blue Mangoes (2002) and Joothan: A Dalit’s Life (2003) respectively, are chosen, as they deal with caste issues. Both the works are sensitive portrayals of the lives of lower- caste people and their attempts at coming in terms with the reality of their shackled existence. It is not to grade the two schools of writings, but to analyze their differences in the way of illustration of the theme of caste as presented in the mainstream writing and regional writing. In order to understand the trends of Mainstream writing and Regional writing, it is indispensable to have an overview on Indian Literature in English and Indian Literature in English Translation. Keywords: Mainstream Writing, Regional Writing, Indian Literature in English, Indian Literature in English Translation. Introduction Literature along with Indian Regional Literature in In a multi – lingual country like India, Indian order to perceive a broader unified vision of national Literature in English cannot be studied in isolation, literature.