MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Study Report

Self Study Report Submitted To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL Bangalore-560072 By Arya Vidyapeeth College (Affiliated to Gauhati University, Guwahati) Gopinath Nagar Guwahati-781016 ASSAM Office of the Principal ARYA VIDYAPEETH COLLEGE: GUWAHATI-781016 Ref. No. AVC/Cert./2015/ Dated Guwahati the 25/12/2015 Certificate of Compliance (Affiliated/Constitutent/Autonomous Colleges and Recognized Institute) This is to certify that Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati-16, fulfills all norms: 1. Stipulated by the affiliating University and/or 2. Regulatory council/Body [such as UGC, NCTE, AICTE, MCI, DCI, BCI, etc.] and 3. The affiliation and recognition [if applicable] is valid as on date. In case the affiliation/recognition is conditional, then a detailed enclosure with regard to compliance of conditions by the institution will be sent. It is noted that NAAC’s accreditation, if granted, shall stand cancelled automatically, once the institution loses its university affiliation or recognition by the regulatory council, as the case may be. In case the undertaking submitted by the institution is found to be false then the accreditation given by the NAAC is liable to be withdrawn. It is also agreeable that the undertaking given to NAAC will be displayed on the college website. Place: Guwahati (Harekrishna Deva Sarmah) Date: 25-12-2015 Principal Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati-16 Self Study Report Arya Vidyapeeth College Page 2 Office of the Principal ARYA VIDYAPEETH COLLEGE: GUWAHATI-781016 Ref. No. AVC/Cert./2015/ Dated Guwahati the 25/12/2015 DECLARATION This is to certify that the data included in this Self Study Report (SSR) is true to the best of my knowledge. -

TNPSC Current Affairs October 2019

Unique IAS Academy – TNPSC Current Affairs October 2019 UNIQUE IAS ACADEMY The Best Coaching Center in Coimbatore NVN Layout, New Siddhapudur, Gandhipuram, Coimbatore Ph: 0422 4204182, 98842 67599 ******************************************************************************************* STATE AFFAIRS MADURAI STUDENT INVITED TO ADDRESS U.N. FORUM: Twenty-one-year-old Premalatha Tamilselvan, a law course aspirant from Madurai, has been invited to attend the Human Rights Council Social Forum to be held at Geneva from October 1. A graduate in History, Ms. Premalatha has been invited to address the forum at the screening of ‗A Path to Dignity: The Power of Human Rights Education‘, a 2012 documentary in which she featured. In the documentary, Ms. Premalatha, then a student of the Elamanur Adi Dravidar Welfare School, spoke on issues relating to caste and gender disparity. CITY POLICE RECEIVES SKOCH AWARDS: The Greater Chennai Police has bagged two awards for the effective implementation of CCTV surveillance - ‗Third Eye‘ project with public partnership and introducing digital technology for cashless payment of fine against traffic violations. The SKOCH Governance Award instituted in 2003 is conferred by an independent organisation, which salutes people, projects and institutions that go the extra mile to make India a better nation. At a function held in New Delhi on Wednesday, Union Minister of Human Resource Development Ramesh Pokhriyal gave away the awards. AT 49%, TN IS NO 3 IN HIGHER EDUCATION GROSS ENROLMENT RATIO: Tamil Nadu emerges as the top performer among the big states in the country, in terms of Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in higher education, at 49%, according to the latest report of All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19 (AISHE). -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

World Cinema Amsterd Am 2

WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM 2011 3 FOREWORD RAYMOND WALRAVENS 6 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM JURY AWARD 7 OPENING AND CLOSING CEREMONY / AWARDS 8 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION 18 INDIAN CINEMA: COOLLY TAKING ON HOLLYWOOD 20 THE INDIA STORY: WHY WE ARE POISED FOR TAKE-OFF 24 SOUL OF INDIA FEATURES 36 SOUL OF INDIA SHORTS 40 SPECIAL SCREENINGS (OUT OF COMPETITION) 47 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM OPEN AIR 54 PREVIEW, FILM ROUTES AND HET PAROOL FILM DAY 55 PARTIES AND DJS 56 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM ON TOUR 58 THANK YOU 62 INDEX FILMMAKERS A – Z 63 INDEX FILMS A – Z 64 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS WELCOME World Cinema Amsterdam 2011, which takes place WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION from 10 to 21 August, will present the best world The 2011 World Cinema Amsterdam competition cinema currently has to offer, with independently program features nine truly exceptional films, taking produced films from Latin America, Asia and Africa. us on a grandiose journey around the world with stops World Cinema Amsterdam is an initiative of in Iran, Kyrgyzstan, India, Congo, Columbia, Argentina independent art cinema Rialto, which has been (twice), Brazil and Turkey and presenting work by promoting the presentation of films and filmmakers established filmmakers as well as directorial debuts by from Africa, Asia and Latin America for many years. new, young talents. In 2006, Rialto started working towards the realization Award winners from renowned international festivals of a long-cherished dream: a self-organized festival such as Cannes and Berlin, but also other films that featuring the many pearls of world cinema. Argentine have captured our attention, will have their Dutch or cinema took center stage at the successful Nuevo Cine European premieres during the festival. -

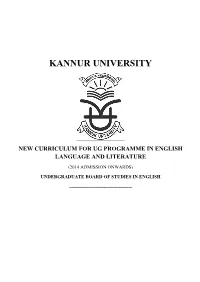

2014-Admn-Syllabus

KANNUR UNIVERSITY NEW CURRICULUM FOR UG PROGRAMME IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (2014 ADMISSION ONWARDS) UNDERGRADUATE BOARD OF STUDIES IN ENGLISH ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 1. Table of Common Courses Sl Sem Course Title of Course Hours/ Credit Marks No: ester Code Week ESE CE Total 1 1 1A01ENG Communicative English I 5 4 40 10 50 2 1 1A02ENG Language Through Literature 1 4 3 40 10 50 3 2 2A03ENG Communicative English II 5 4 40 10 50 4 2 2A04ENG Language Through Literature II 4 3 40 10 50 5 3 3A05ENG Readings in Prose and Poetry 5 4 40 10 50 6 4 4A06ENG Readings in Fiction and Drama 5 4 40 10 50 2. Table of Core Courses Sl Seme Course Title of course Hours/ Credit Marks No: ster code Week ESE CE Total 1 1 1B01ENG History of English Language 6 4 40 10 50 and Literature 2 2 2B02ENG Studies in Prose 6 4 40 10 50 3 3 3B03ENG Linguistics 5 4 40 10 50 4 3 3B04ENG English in the Internet Era 4 4 40 10 50 5 4 4B05ENG Studies in Poetry 4 4 40 10 50 6 4 4B06ENG Literary Criticism 5 5 40 10 50 7 5 5B07ENG Modern Critical Theory 6 5 40 10 50 8 5 5B08ENG Drama: Theory and Literature 6 4 40 10 50 9 5 5B09ENG Studies in Fiction 6 4 40 10 50 10 5 5B10ENG Women‘s Writing 5 4 40 10 50 11 6 6B11ENG Project 1 2 20 5 25 12 6 6B12ENG Malayalam Literature in 5 4 40 10 50 Translation 13 6 6B13ENG New Literatures in English 5 4 40 10 50 14 6 6B14ENG Indian Writing in English 5 4 40 10 50 15 6 6B15ENG Film Studies 5 4 40 10 50 16 6 6B16ENG Elective 01, 02, 03 4 4 40 10 50 3. -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

Morphotectonic Study in a Part of Indo-Burmese Ranges in Eastern Mizoram, India

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (July - December 2018), pp. 81-92 Research Article Open Access Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies A Journal of Pachhunga University College ISSN: 2456-3757 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Vol. 03, No. 02 July-Dec., 2018 Journal Website: https://sjms.mizoram.gov.in Morphotectonic Study in a part of Indo-Burmese Ranges in Eastern Mizoram, India Farha Zaman1,*, Devojit Bezbaruah1, Lalhmingsangi2 & Raghupratim Rakshit1 1Dept. of Applied Geology, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh, Assam 2Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract Mizoram fold belt, situated in geologically complex Indo-Burmese Ranges, comprises of arcuate sedimentary belt. This NS trending mountain series is cut by a number of parallel to subparallel NNE-SSW, NE-SW, and NW-SE tectonic features like faults, deformed hill ranges etc. This research work was carried out in Champhai district of eastern Mizoram, near Indo- Myanmar border. In this study, a morphotectonic analysis has been performed to know the presence of active tectonics for the region. Morphotectonic parameters were calculated for 32 basins of 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th order basins. Tuipui River had been originated near Champhai town which is supposed to be a paleo-lake. The two major rivers Tuipui and Tayo have similar entrench meander patterns which might have been controlled by some structural features. Most of the other drainage shows rectangular, trellis, oval and circular pattern along with the unique river meanders. The eastern basins of the Tuipui river mostly shows WNW highly asymmetrical (|AF|=IV) tilted basins whereas the western basins shows SE moderately asymmetrical (|AF|=III) tilted basins. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae (As on August, 2021) Dr. Biswaranjan Mistri Professor in Geography The University of Burdwan, Burdwan, West Bengal-713104, India (Cell: 09433310867; 9064066127, Email: [email protected]; [email protected]) Date of Birth: 9th September, 1977 Areas of Research Interest: Environmental Geography, Soil and Agriculture Geography Google Scholar Citation: https://scholar.google.co.in/citations?user=xpIe3RkAAAAJ&hl=en Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Biswaranjan-Mistri Educational Qualifications 1. B.Sc.( Hons.) in Geography with Geology and Economics, Presidency College; University of Calcutta, (1999) 2. M.A. in Geography, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, ( 2001) 3. M.A. in Philosophy, The University of Burdwan (2017) 4. Ph.D.(Geography), Titled: “Environmental Appraisal and Land use Potential of South 24 Parganas, West Bengal”, University of Calcutta, Kolkata (2013) 5. (i ) NET/UGC (Dec,2000), in Geography (ii) JRF/CSIR (July, 2001), in EARTH, ATMOSPHERIC, OCEAN AND PLANETARY SCIENCES along with SPMF call for (June, 2002) (iii) NET/UGC (Dec, 2001), in Geography (iv) JRF/UGC (June, 2002), in Geography Attended in Training Course/ Workshop (Latest First) 1. Workshop on “Student Guidance, Counseling and Career Planning” organized by Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, 25th August, 2018 to 31st August, 2018. 2. UGC Sponsored Short Term Course on “Environmental Science” organized by UGC- Human Resource Development Centre, The University of Burdwan, 24th May, 2016- 30th May, 2016. 3. UGC Sponsored Short Term Course on “Remote Sensing and GIS” organized by Human Resource Development Centre, The University of Burdwan, 29th December, 2015 - 4th January, 2016. 4. UGC Sponsored Short Term Course on “Human Rights” organized by Human Resource Development Centre , The University of Burdwan, June 24-30, 2015 5. -

The Winning Woman of Hindi Cinema

ADVANCE RESEARCH JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE A CASE STUDY Volume 5 | Issue 2 | December, 2014 | 211-218 e ISSN–2231–6418 DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ARJSS/5.2/211-218 Visit us : www.researchjournal.co.in The winning woman of hindi cinema Kiran Chauhan* and Anjali Capila Department of Communication and Extension, Lady Irwin College, Delhi University, DELHI (INDIA) (Email: [email protected]) ARTICLE INFO : ABSTRACT Received : 27.05.2014 The depiction of women as winners has been analyzed in four sets of a total of eleven films. The Accepted : 17.11.2014 first two sets Arth (1982) and Andhi (1975) and Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam (1962), Sahib Bibi aur Gangster (2011), Sahib Bibi aur Gangster returns (2013), explore the woman in search for power within marriage. Arth shows Pooja finding herself empowered outside marriage and KEY WORDS : without any need for a husband or a lover. Whereas in Aandhi, Aarti wins political power and Winning Woman, Hindi Cinema returns to a loving marital home. In Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam choti bahu after a temporary victory of getting her husband back meets her death. In both films Sahib Bibi aur Gangster and returns, the Bibi eliminates the other woman and gangster, deactivates the husband and wins the election to gain power. she remains married and a Rani Sahiba. In the set of four Devdas makes and remakes (1927–2009) Paro is bold, shy, glamorous and ultimately liberated (Dev, 2009). Chanda moves from the looked down upon, prostitute, dancing girl to a multilingual sex worker who is empowering herself through education and treating her occupation as a stepping stone to HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE : empowerment. -

Project Staff

Project Staff Thanhlupuia : Research Officer Ruth Lalrinsangi : Inspector of Statistics Lalrinawma : Inspector of Statistics Zorammawii Colney : Software i/c Lalrintluanga : Software i/c Vanlalruati : Statistical Cell Contents Page No. 1. Foreword - (i) 2. Preface - (ii) 3. Message - (iii) 4. Notification - (iv) Part-A (Abstract) 1. Dept. of School Education, Mizoram 2009-2010 at a Glance - 1 2. Number of schools by management - 2 3. Enrolment of students by management-wise - 3 4. Number of teachers by management-wise - 4 5. Abstract of Primary Schools under Educational Sub-Divisions - 5-9 6. Abstract of Middle Schools under Educational Sub-Divisions - 10-16 7. Abstract of High Schools under Educational Districts - 17-18 8. Abstract of Higher Secondary Schools under Educational Districts - 19-23 Part-B (List of Schools with number of teachers and enrolment of students) PRIMARY SCHOOLS: Aizawl District 1.SDEO, AizawlEast - 25-30 2.SDEO, AizawlSouth - 31-33 3.SDEO, AizawlWest - 34-38 4. SDEO, Darlawn - 39-41 5.SDEO, Saitual - 42-43 Champhai District 6.SDEO, Champhai - 44-47 7. SDEO, Khawzawl - 48-50 Kolasib District 8. SDEO, Kolasib - 51-53 9. SDEO, Kawnpui - 54-55 Lawngtlai District 10. EO, CADC - 56-59 11. EO, LADC - 60-64 Lunglei District 12.SDEO, LungleiNorth - 65-67 13.SDEO, LungleiSouth - 68-70 14.SDEO, Lungsen - 71-74 15. SDEO, Hnahthial - 75-76 Mamit District 16. SDEO, Mamit - 77-78 17. SDEO, Kawrthah - 79-80 18.SDEO, WestPhaileng - 81-83 Saiha District 19. EO, MADC - 84-87 Serchhip District 20. SDEO, Serchhip - 88-89 21. SDEO, North Vanlaiphai - 90 22.SDEO, Thenzawl - 91 MIDDLE SCHOOLS: Aizawl District 23.SDEO, Aizawl East - 93-97 24.SDEO, AizawlSouth - 98-99 25. -

Of Grandeur and Valour: Bollywood and Indiaís Fighting Personnel 1960-2005

OF GRANDEUR AND VALOUR: BOLLYWOOD AND INDIAíS FIGHTING PERSONNEL 1960-2005 Sunetra Mitra INTRODUCTION Cinema, in Asia and India, can be broadly classified into three categoriesópopular, artistic and experimental. The popular films are commercial by nature, designed to appeal to the vast mass of people and to secure maximum profit. The artistic filmmaker while not abandoning commercial imperatives seeks to explore through willed art facets of indigenous experiences and thought worlds that are amenable to aesthetic treatment. These films are usually designated as high art and get shown at international film festivals. The experimental film directors much smaller in number and much less visible on the film scene are deeply committed to the construction of counter cinema marked by innovativeness in outlook and opposition to the establishment (Dissanayke, 1994: xv-xvi). While keeping these broad generalizations of the main trends in film- making in mind, the paper engages in a discussion of a particular type of popular/ commercial films made in Bollywood1. This again calls for certain qualifications, which better explain the purpose of the paper. The paper attempts to understand Bollywoodís portrayal of the Indian military personnel through a review of films, not necessarily war films but, rather, through a discussion of themes that have war as subject and ones that only mention the military personnel. The films the paper seeks to discuss include Haqeeqat, Border, LOC-Kargil, and Lakshya that has a direct reference to the few wars that India fought in the post-Independence era and also three Bollywood blockbusters namely Aradhana, Veer-Zara and Main Hoon Na, the films that cannot be dubbed as militaristic nor has reference to any war time scenario but nevertheless have substantial reference to the army. -

The Naga Language Groups Within the Tibeto-Burman Language Family

TheNaga Language Groups within the Tibeto-Burman Language Family George van Driem The Nagas speak languages of the Tibeto-Burman fami Ethnically, many Tibeto-Burman tribes of the northeast ly. Yet, according to our present state of knowledge, the have been called Naga in the past or have been labelled as >Naga languages< do not constitute a single genetic sub >Naga< in scholarly literature who are no longer usually group within Tibeto-Burman. What defines the Nagas best covered by the modern more restricted sense of the term is perhaps just the label Naga, which was once applied in today. Linguistically, even today's >Naga languages< do discriminately by Indo-Aryan colonists to all scantily clad not represent a single coherent branch of the family, but tribes speaking Tibeto-Burman languages in the northeast constitute several distinct branches of Tibeto-Burman. of the Subcontinent. At any rate, the name Naga, ultimately This essay aims (1) to give an idea of the linguistic position derived from Sanskrit nagna >naked<, originated as a titu of these languages within the family to which they belong, lar label, because the term denoted a sect of Shaivite sadhus (2) to provide a relatively comprehensive list of names and whose most salient trait to the eyes of the lay observer was localities as a directory for consultation by scholars and in that they went through life unclad. The Tibeto-Burman terested laymen who wish to make their way through the tribes labelled N aga in the northeast, though scantily clad, jungle of names and alternative appellations that confront were of course not Hindu at all.