Irish Women Artists 1870 - 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NGI Annual Report 2009 Web NGI Annual Report2001

G AILEARAÍ N ÁISIÚNTA NA HÉ IREANN N ATIONAL G ALLERY of I RELAND T UARASCÁIL B HLIANTÚIL 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT 2009 GAILEARAÍ NÁISIÚNTA NA HÉIREANN Is trí Acht Parlaiminte i 1854 a bunaíodh Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann, agus osclaíodh don phobal é i 1864. Tá breis agus 13,000 mír ann: breis agus 2,500 olaph- ictiúr, agus 10,000 píosa oibre i meáin éagsúla, lena n-áirítear uiscedhathanna, líníochtaí, priontaí agus dealbhóireacht. Is ón gceathrú céad déag go dtí an la inniu a thagann na píosaí oibre, agus tríd is tríd léirítear iontu forbairt na mórscoileanna péin- téireachta san Eoraip: Briotanach, Dúitseach, Pléimeannach, Francach, Gearmánach, Iodálach, Spáinneach agus an Ísiltír, comhlánaithe ag bailiúchán cuimsitheach d’Ealaín ó Éirinn. Ráiteas Misin Tá sé mar chuspóir ag Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann an bailúchán náisiúnta a thais- peáint, a chaomhnú, a bhainistiú, a léirmhíniú agus a fhorbairt; chun taitneamh agus tuiscint ar na hamharcealaíona a fheabhsú, agus chun saol cultúrtha, ealaíonta agus intleachtúil na nglúinte reatha agus na nglúinte sa todhchaí a fheabhsú freisin. NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND The National Gallery of Ireland was founded by an Act of Parliament in 1854 and opened to the public in 1864. It houses some 13,000 items: over 2,500 oil paintings, and 10,000 works in different media including watercolours, drawings, prints and sculpture. The works range in date from the fourteenth century to the present day and broadly represent the development of the major European schools of painting: British, Dutch, Flemish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Netherlands, complemented by a comprehensive collection of Irish art. -

Annual Report Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 ISBN: 978-1-904291-57-2

annual report tuarascáil bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 ISBN: 978-1-904291-57-2 The Arts Council t +353 1 618 0200 70 Merrion Square, f +353 1 676 1302 Dublin 2, D02 NY52 Ireland Callsave 1890 392 492 An Chomhairle Ealaíon www.facebook.com/artscouncilireland 70 Cearnóg Mhuirfean, twitter.com/artscouncil_ie Baile Átha Cliath 2, D02 NY52 Éire www.artscouncil.ie Trophy part-exhibition, part-performance at Barnardo Square, Dublin Fringe Festival. September 2017. Photographer: Tamara Him. taispeántas ealaíne Trophy, taibhiú páirte ag Barnardo Square, Féile Imeallach Bhaile Átha Cliath. Meán Fómhair 2017. Grianghrafadóir: Tamara Him. Body Language, David Bolger & Christopher Ash, CoisCéim Dance Theatre at RHA Gallery. November/December 2017 Photographer: Christopher Ash. Body Language, David Bolger & Christopher Ash, Amharclann Rince CoisCéim ag Gailearaí an Acadaimh Ibeirnigh Ríoga. Samhain/Nollaig 2017 Grianghrafadóir: Christopher Ash. The Arts Council An Chomhairle Ealaíon Who we are and what we do Ár ról agus ár gcuid oibre The Arts Council is the Irish government agency for Is í an Chomhairle Ealaíon an ghníomhaireacht a cheap developing the arts. We work in partnership with artists, Rialtas na hÉireann chun na healaíona a fhorbairt. arts organisations, public policy makers and others to build Oibrímid i gcomhpháirt le healaíontóirí, le heagraíochtaí a central place for the arts in Irish life. ealaíon, le lucht déanta beartas poiblí agus le daoine eile chun áit lárnach a chruthú do na healaíona i saol na We provide financial assistance to artists, arts organisations, hÉireann. local authorities and others for artistic purposes. We offer assistance and information on the arts to government and Tugaimid cúnamh airgeadais d'ealaíontóirí, d'eagraíochtaí to a wide range of individuals and organisations. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

Moving Ahead with the Stevens Competition

the WORSHIPFUL COMPANY of GLAZIER S & PAINTERS OF GLASS Issue Number 63 Spring 20 21 the 2020 competition or do it differently. Then came lockdown two! No problem, Moving ahead We chose the latter. we have been here before. We reintroduced Firstly, we delayed the entry date by four the Design Only category and sat back. with the Stevens months in the hope that lockdown would be Inevitably, lockdown three arrived, so the eased in time for participants to complete entry date has been delayed to July and Competition their work. This worked. Secondly, we Prizegiving until October. Judging will be introduced a new type of entry, Design Only, virtual again and we have a panel of judges BRIAN GREEN reports: Organising the which allowed competitors to submit their who are looking forward to the challenge. Stevens Competition in 2020 and 2021 has design but removed the need to produce a The delay has been used to widen the been quite a game! So far, the Glaziers are sample panel. This worked; roughly 40% of potential field of entry; translations of the in the lead and we intend to keep it that way. the entries fell into this category. Thirdly, the brief have been circulated in Spanish, French The original game plan for Stevens 2020 decision was taken to judge the competition and German. had to be abandoned when the country online. This worked surprisingly well. We hope Stevens 2022 will be more went into the first lockdown in March 2020 At the end of the day the Prizegiving was straightforward. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Homage to Fra Angelico (1928) Oil on Canvas, 183 X 152.5Cms (72 X 60’’)

38 31 Mainie Jellett (1897-1944) Homage to Fra Angelico (1928) Oil on canvas, 183 x 152.5cms (72 x 60’’) Provenance: From the Collection of Dr. Eileen MacCarvill, Fitzwilliam Square, Dublin Exhibited: Mainie Jellett Exhibition, Dublin Painters Gallery 1928 Irish Exhibition of Living Art, 1944, Cat. No. 91 An Tostal-Irish Painting 1903-1953, The Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, Dublin 1953 Mainie Jellett Retrospective 1962, Hugh Lane Gallery Cat. No. 38 Irish Art 1900-1950, Cork ROSC 1975, The Crawford Gallery, Cork, 1975, Cat. No. 65 The Irish Renaissance, Pyms Gallery, London, 1986, Cat. No. 39 Mainie Jellett Retrospective 1991/92, Irish Museum of Modern Art Cat. No. 89 The National Gallery of Ireland, New Millennium Wing, Opening Exhibition of 20th Century Irish Paintings, January 2002-December 2003 The Collectors’ Eye, The Model Arts & Niland Gallery, Sligo, January-February 2004, Cat. No. 12; The Hunt Museum, Limerick, March-April 2004 A Celebration of Irish Art & Modernism, The Ava Gallery, Clandeboye, June- September 2011, Cat. No 21 Analysing Cubism Exhibition Irish Museum of Modern Art Feb/May 2013, The Crawford Gallery Cork June / August 2014 and The FE Mc William Museum September/November 2013 Irish Women Artists 1870 - 1970 Summer loan exhibition Adams Dublin July 2014 and The Ava Gallery , Clandeboye Estate August/September Cat. No. 70. Literature: The Irish Statesman, 16th June 1928 Stella Frost, A Tribute to Evie Hone & Mainie Jellett, Dublin 1957, pp19-20 Kenneth McConkey, A Free Spirit-Irish Art 1860-1960, 1990, fig 58 p75 Dr. S.B. Kennedy, Irish Art & Modernism, 1991, p37 Bruce Arnold, Mainie Jellett and the Modern Movement in Ireland, 1991, full page illustration p120 Mainie Jellett, IMMA Cat, No. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

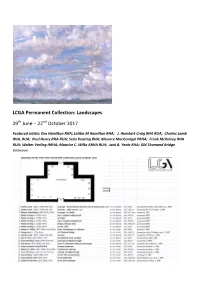

Landscapes from Permanent Collection June

LCGA Permanent Collection: Landscapes 29th June – 22nd October 2017 Featured artists: Eva Hamilton RHA; Letitia M Hamilton RHA; J. Humbert Craig RHA RUA; Charles Lamb RHA, RUA; Paul Henry RHA RUA; Seán Keating RHA; Maurice MacGonigal PRHA; Frank McKelvey RHA RUA; Walter Verling HRHA; Maurice C. Wilks ARHA RUA; Jack B. Yeats RHA; Old Thomond Bridge Unknown. Charles Lamb RHA, RUA (1893–1964): The Irish landscape artist, portrait and figure painter Charles Vincent Lamb was born in Portadown, Co. Armagh. and worked as a house painter before teaching art and painting professionally. He studied life-drawing in Belfast School of Art before winning a scholarship to the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art in 1917, where he came under the influence of Sean Keating. He began exhibiting at the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1919, and thereafter averaged about 4 paintings per show until his final years. In 1922 he went to Connemara, settling in a remote Irish-speaking part of County Galway, Carraroe. Lamb was one of a group of painters, including Sean Keating, Patrick Tuohy and Paul Henry, who found their inspiration in the West of Ireland, which was seen as the repository of true Irishness. In 1938 he was elected a full member of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA). He continued painting actively right up until his death in 1964. Maurice MacGonigal PRHA (1900- 1979): The landscape and portrait artist MacGonigal was born in Dublin, becoming a design apprentice in his uncle's firm, Joshua Clark, ecclesiastical decorator and stained glass artist. MacGonigal mixed politics with art studies, managing within a few years to be interned at Ballykinlar Camp, take drawing and figure drawing classes at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (now the National College of Art and Design) and win the Taylor Scholarship in painting. -

SIOBHÁN HAPASKA Born 1963, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Lives and Works in London, United Kingdom

SIOBHÁN HAPASKA Born 1963, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Lives and works in London, United Kingdom. Education 1985-88 Middlesex Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom. 1990-92 Goldsmiths College, London, United Kingdom. Solo Exhibitions 2021 Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2020 LOK, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. 2019 Olive, Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Paris, France. Snake and Apple, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom. 2017 Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2016 Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Sweden. 2014 Sensory Spaces, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 2013 Hidde van Seggelen Gallery, London, United Kingdom. Siobhán Hapaska, Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden. 2012 Siobhán Hapaska and Stephen McKenna, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Sweden. 2011 A great miracle needs to happen there, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2010 The Nose that Lost its Dog, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. The Curve Gallery, the Barbican Art Centre, London, United Kingdom. Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast, United Kingdom. 2009 The Nose that Lost its Dog, Glasgow Sculpture Studios Fall Program, Glasgow, United Kingdom. 2007 Camden Arts Centre, London, United Kingdom. Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. 2004 Playa de Los Intranquilos, Pier Gallery, London, United Kingdom. 2003 cease firing on all fronts, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2002 Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. 2001 Irish Pavillion, 49th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy. 1999 Sezon Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan. Artist Statement for Bonakdar Jancou Gallery, Basel Art Fair, Basel, Switzerland. Tokyo International Forum, Yuraku-Cho Saison Art Program Gallery, Aoyama, Tokyo, Japan. 1997 Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. Ago, Entwistle Gallery, London, United Kingdom. Oriel, The Arts Council of Wales' Gallery, Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom. -

The Life and Works of Beatrice Elvery, 1881-1920

Nationalism, Motherhood, and Activism: The Life and Works of Beatrice Elvery, 1881-1920 Melissa S. Bowen A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History May 2015 Copyright By Melissa S. Bowen 2015 Acknowledgments I am incredibly grateful for the encouragement and support of Cal State Bakersfield’s History Department faculty, who as a group worked closely with me in preparing me for this fruitful endeavor. I am most grateful to my advisor, Cliona Murphy, whose positive enthusiasm, never- ending generosity, and infinite wisdom on Irish History made this project worthwhile and enjoyable. I would not have been able to put as much primary research into this project as I did without the generous scholarship awarded to me by Cal State Bakersfield’s GRASP office, which allowed me to travel to Ireland and study Beatrice Elvery’s work first hand. I am also grateful to the scholars and professionals who helped me with my research such as Dr. Stephanie Rains, Dr. Nicola Gordon Bowe, and Rector John Tanner. Lastly, my research would not nearly have been as extensive if it were not for my hosts while in Ireland, Brian Murphy, Miriam O’Brien, and Angela Lawlor, who all welcomed me into their homes, filled me with delicious Irish food, and guided me throughout the country during my entire trip. List of Illustrations Sheppard, Oliver. 1908. Roisin Dua. St. Stephen's Green, Dublin. 2 Orpen, R.C. 1908. 1909 Seal. The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland, Dublin. -

An Artistic Praxis: Phenomenological Colour and Embodied Experience

Journal of the International Colour Association (2017): 17, 150-200 Balabanoff An Artistic Praxis: Phenomenological colour and embodied experience Doreen Balabanoff Faculty of Design, OCAD University, Toronto, Canada Email: [email protected] Artistic knowledge resides within the works that a visual artist makes. .Verbalising or discussing that knowledge is a separate exercise, often left to others, who make their own interpretations and investigations. In this introspective study of artworks spanning four decades, I look into and share insight about a practice in which knowledge about colour, light and spatial experience was developed and utilised. The process of action, reflection and new application of gained knowledge is understood as a praxis—a practice aimed at creating change in the world. The lessons learned are about human embodied experience of light, colour and darkness in spatial environments. The intent of the study (as of the artwork) is enhancement of our capacities for creating sensitive and enlivening space for human life experience and human flourishing, through understanding and use of colour and light as complex environmental phenomena affecting our mind/body/psyche. Four themes arose from reflecting upon the work. These are, in order of discussion: (1) Image and Emanation, (2) Resonance and Chord, (3) Threshold and Veil, and (4) Projection, Reflection, Light and Time. My findings include affirmation that a Goethian science (phenomenological, observational) approach to investigating and unconcealing tacit knowledge—embedded in an artistic praxis and its outcomes—has value for developing a deeper understanding of environmental colour and light. Such knowledge is important because environmental design has impact upon our bodies, our minds and our life experience.