The Colonial Bar and the American Revolution, 60 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

Action-Reaction … the Road to Revolution

Name:____________________________________ Class Period:_____ Action-Reaction … The Road to Revolution APUSH Guide for American Pageant chapter 7 & 2nd half of AMSCO chapter 4 (and a bit from chapter 8 Pageant and chapter 5 AMSCO) Directions Print document and take notes in the spaces provided. Read through the guide before you begin reading the chapter. This step will help you focus on the most significant ideas and information And as you read. Purpose These notes are not “hunt and peck” or “fill in the blank” notes. Think of this guide as a place for reflections and analysis using your noggin (thinking skills) and new knowledge gained from the reading. Mastery of the course and AP exam await all who choose to process the information as they read/receive. To what extent was America a revolutionary force from the first days of European discovery? Assessment: __________________________ Small extent? Large extent? Evidence to support your assessment: Evidence to support the opposing view: 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. Explain the impact of the following statement in terms of America. “Distance weakens authority; great weakness weakens authority greatly.” The Impact of Mercantilism Explain how Americans were supposed to ensure Britain’s economic and naval supremacy. What impact did this have on colonists? What was the problem with having no banks in the colonies? How did Parliament respond to colonies issuing paper money? How did English policy regarding its North American colonies change after the French and Indian War, Pontiac’s Rebellion, and the Proclamation of 1763? From Salutary Neglect to…. For each of the items listed below, identify the Before the actual war of the Revolution Action (English purpose/goal) and the could begin, there had to be a Reaction of the colonists. -

Chapter 3 America in the British Empire

CHAPTER 3 AMERICA IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE The American Nation: A History of the United States, 13th edition Carnes/Garraty Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE BRITISH COLONIAL SYSTEM n Colonies had great deal of freedom after initial settlement due to n British political inefficiency n Distance n External affairs were controlled entirely by London but, in practice, the initiative in local matters was generally yielded to the colonies n Reserved right to veto actions deemed contrary to national interest n By 18 th Century, colonial governors (except Connecticut and Rhode Island) were appointed by either the king or proprietors Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE BRITISH COLONIAL SYSTEM n Governors n executed local laws n appointed many minor officials n summoned and dismissed the colonial assemblies n proposed legislation to them n had power to veto colonial laws n They were also financially dependent on their “subjects” Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE BRITISH COLONIAL SYSTEM n Each colony had a legislature of two houses (except Pennsylvania which only had one) n Lower House: chosen by qualified voters, had general legislative powers, including control of purse n Upper House: appointed by king (except Massachusetts where elected by General Court) and served as advisors to the governor n Judges were appointed by king n Both judges and councilors were normally selected from leaders of community n System tended to strengthen the influence of entrenched colonials n Legislators -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

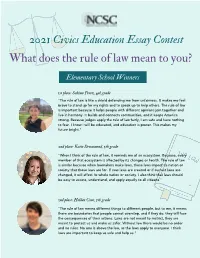

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

Notes and Documents

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS Thomas Paine's Response to Lord North's Speech on the British Peace Proposals Thomas Paine, whose book Common Sense proposed the formation of a "declaration for independence'* and stirred thousands to the cause of inde- pendence in 1776, supported the cause throughout the war effort with his American Crisis series of pamphlets and numerous newspaper publications. The newspapers played a crucial role in the American Revolution by supply- ing a war of words, which kept the colonists focused on their goal of inde- pendence. The printers had become active participants early in the war par- tially due to their anger at the British Stamp Act, which taxed newspapers.1 Writers, using multiple pseudonyms to mask their identities and produce an appearance of greater numbers, produced poems, essays, and letters for the newspapers to combat loyalists as well as the pernicious effects of fear and ignorance among the colonists.2 Paine's use of pseudonyms kept some of his newspaper contributions from being identified for many years. In 1951 A. Owen Aldridge identified a number of pieces, including an article written by Paine in York, Pennsyl- vania, on June 10,1778, and published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on June 13, 1778, signed "Common Sense," which had not been included in the published canon of Paine's writings.3 Similarly, it appears that Paine contrib- uted a letter and associated commentary in the April 25,1778, "Postscript" edition of the Pennsylvania Packet^ published in Lancaster, which has also been overlooked. Addressed to "R. L." and signed "T. P.," there is ample 1 Philip Davidson, Propaganda and the American Revolution 1763-1783 (Chapel Hill, 1941), 226. -

The Anglo-American World in the Long Eighteenth Century

L1 – Semester 2 Introduction à la civilisation des Pays Anglophones The Anglo-American World in the Long Eighteenth Century Anne-Claire Faucquez Département d’Etudes des Pays Anglophones 2 The Anglo-American World in the Long Eighteenth Century METHODOLOGY Primary vs secondary sources Reading primary sources : An introduction Written Document Analysis Worksheet Poster and Cartoon Analysis Worksheet To comment on iconographic documents To comment on graphs and statistics Timeline of events in 17th and 18th century England and America Test your knowledge on American and British institutions Chapter 1: The religious revolution in England 1. The Reformation and the formation of Anglicanism 2. Puritanism and the diversity of Protestant branches 3. Protestantism in America Chapter 2: The evolution of political institutions 1. The Glorious Revolution 2. British politics in the 18th century 3. British society in the 18th century Chapter 3: Colonization in America 1. Who colonized North America? 2. The 13 colonies 3. The Atlantic Slave Trade Chapter 4: The road to the revolution 1. American reactions to the Glorious Revolution 2. The growth of political independence 3. The American War of Independence Course description Assessment: Presence/Participation/Homework: 30% Midterm evaluation: 30% Final exam: 40% My contact information : Email : [email protected] Blog : acfaucquez.wordpress.com 3 PRIMARY VS SECONDARY SOURCES 1. PRIMARY SOURCES = a first-hand account of a past event ▪ Historical newspapers ▪ Documentary photographs ▪ Works of art, literature, or music ▪ Eyewitness accounts or testimony ▪ Interviews ▪ Diaries, journals, or letters ▪ Statutes, laws, or regulations ▪ Speeches, legal decisions, or case law ▪ Archaeological or historical artifacts ▪ Survey research 2. -

Otis Speech on Writs of Assistance

Copyright OUP 2013 AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM VOLUME I: STRUCTURES OF GOVERNMENT Howard Gillman • Mark A. Graber • Keith E. Whittington Supplementary Material Chapter 2: The Colonial Era – Judicial Power and Constitutional Authority James Otis, Part of Speech before the Superior Court of Massachusetts on the Writs of Assistance (1761)1 3 In 1761, the Superior Court of Massachusetts heard arguments on whether it should issue writs of assistance to colonial custom officials who were attempting to enforce British trade laws against local1 merchants smuggling goods. The writs would provide legal authority for officials to conduct forcible searches, on their own initiative, of private property throughout the Boston area. Before the court, James Otis raised what quickly became famous objections to the legality and constitutionality of the writs. 0 The argument of Otis particularly stood out for its assertion that an act authorizing writs of general assistance would be unconstitutional and therefore void. In support of this assertion, Otis 2cited Dr. Bonham’s Case (8 Co. 107a [1610]), in which the great English jurist Sir Edward Coke asserted that “in many cases, the common law will control acts of parliament, and sometimes adjudge them utterly void: for when an act of parliament is against common right and reason, or repugnant, or impossible to be performed, the common law will control it, and adjudge such act to be void.” The argument was subsequently important forP helping to lay the basis for the development of American judicial review after the Revolution. The Superior Court did not rule immediately, but instead sought further information from England as to whether such writs were still in use there. -

Causes of the American Revolution

Revolutionary War By: Kayden Hickle Table of Contents Chapter 1…. Overview Chapter 2…. Boston Tea Party Chapter 3…. Personal point of view Chapter 4…. Essay Overview Chapter 1 Do you know why the American Revolution War happened? The French and Indian War happened before American Revolution War. Britain lost a lot of money for the war and decided to tax the Colonists ( The Americans ) with Acts ,Tea Act, Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Quartering Act. The colonists were mad about the Boston Massacre and decided to go on three tea carrying ships and crack open all the tea crates and dumped it all in the water. They did the Boston Tea Party dressed as Indians then that’s when all the Redcoats came and attacked the people. Paul Revere warned all the people that the “The British are coming-repeat” that was the Battle of Lexington and Concord. The British came and that is when it started. Boston Tea Party Chapter 2 Have you ever wondered why the Boston Tea Party ever happened? In 1773 the Colonists were taxed with Acts called Tea Tax, Sugar Acts, Stamp Acts, and the Quartering Acts because the British lost a lot of money ( pounds in the U.K.) from the French and Indian War. The Boston Massacre happened because the Colonists were still angry at King George III for taxing us. Many people died in The Boston Massacre. The Boston Tea Party occurred on 12/16/1773 Colonists were angry and we boarded the Beaver, Dartmouth, & Eleanor. The only ships that were at the Boston Harbor with tea crates and barrels.