Editors' Introduction: New Dimensions in the Scholarship and Practice Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph Maradiaga Collection CEMA 35

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8639rd9 No online items Guide to the Ralph Maradiaga collection CEMA 35 Finding aid prepared by Mari Khasmanyan, 2015. UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2015 October 26 Guide to the Ralph Maradiaga CEMA 35 1 collection CEMA 35 Title: Ralph Maradiaga collection Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 35 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 22.1 linear feet(4 document boxes, 3 binder boxes, 2 oversized boxes, 165 posters, 41 audio recordings, and 150 video recordings). Date (bulk): Bulk, 1973-1983 Date (inclusive): 1963-1993 Abstract: The Ralph Maradiaga Collection covers Maradiaga's educational, professional and creative accomplishments. They are recorded in exhibit materials, poetry, posters and other papers. Many slides and photos are part of this collection as well. The photos cover much of his personal and professional life as an artist. Included are also numerous audio and video recordings. These recordings cover his extensive involvement in filmmaking as a producer and director. Physical Location: Del Norte (Boxes 1-7), Del Norte Oversized (Boxes 8-9), Del Norte map case (posters). There are some videos from this collection that are available for streaming online, links are provided in the video section. Language of Materials: The collection is predominantly in English, with some Spanish materials. creator: Maradiaga, Ralph Access Restrictions Collection is open for research. -

Greenlining's 25Th Annual Economic Summit

510.926.4001 tel The Greenlining Institute 510.926.4010 fax The Greenlining Institute Oakland, California @Greenlining GREENLINING’S 25TH ANNUAL ECONOMIC SUMMIT www.greenlining.org @Greenlining e come together for The Greenlining Institute’s 26th annual Economic Summit at a moment that feels special and pivotal. On the one hand, we face continuing attacks on communities of color and on others who are too often marginalized in this Wsociety. But in 2018, we saw that people of color will no longer just play defense against attacks on our rights; we will lead America toward a vision of equity and justice. That’s why this year’s Summit theme takes its inspiration from the words of Representative Maxine Waters – that famous “reclaiming my time” moment that so quickly went viral – in order to highlight the leaders, especially here in California, who refuse to stay silent in the face of injustice. We invite you to listen and be inspired by such stellar figures as Representative Barbara Lee, our Lifetime Achievement Award winner, California Public Utilities Commissioner Martha Guzman Aceves, She The People founder Aimee Alison, Dream Corps President Vien Truong, and acclaimed rapper, activist, producer, screenwriter and film director Boots Riley, among many others. But we also hope you’ll join our interactive Equity Lab in the afternoon and explore practical tools to move the struggle for justice and equity from thinking to doing. And today we will also be saying a very special farewell to Orson Aguilar as he transitions out of Greenlining after 11 years as our President. Orson first came to Greenlining through our Leadership Academy as a young leader more than 20 years ago. -

SI Calendar June20updated

2017 MALCS Summer Institute – Final Draft 06.27.2017 *Tuesday, July 18. Board Meeting. 9:00am-5:00pm Wednesday July 19, 2017 [EC/CC Meeting (if needed): 9:00am-12:00pm] Pre-Institute Professional, Emotional Well-Being, and Academic Workshops *Pre-Registration Required for Workshops A1-2, and B1-2. (Email At-Large Representative Dr. Sandra M. Pacheco [email protected] to register) 9am-12pm A1. Demystifying Academic Writing with Dr. Wanda Alarcon Writing is hard. The reasons are not always mechanical yet it helps to have an understanding of some of the forms in which undergraduate and graduate students are expected to write. The goals of this workshop include: introduction to academic genres; a discussion on revision; handy tips to strengthen writing. This writing workshop is geared toward undergrads and graduate students. Workshop is limited to 16 participants. A2. Healing Workshop: Remedios y Rituales Curanderas sin Fronteras will provide an interactive workshop where participants will learn how to make different remedios they can take home. The focus will be on hierbas and remedios for stress and protection. There is a small sliding scale fee of $10-$15 for materials. Limited to 20 participants. 1pm-4pm B1. Creating a Rhythm and Schedule for your Writing with Dr. Cindy Cruz Advanced grad students, post docs, and early career faculty are invited to participate in a pre-institute workshop on writing time management. Participants will: • Build skills on writing time management in academia • Learn about embodied decolonial practice, and negotiating time, research, teaching, and service • Centralize the epistemology of the "Brown" body, Person of Color, and Queer Person of Color, to help us see the body as a site of knowledge to frame agency in academia. -

Copyright by Alan Eladio Gómez 2006

Copyright by Alan Eladio Gómez 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Alan Eladio Gómez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “From Below and to the Left”: Re-Imagining the Chicano Movement through the Circulation of Third World Struggles, 1970-1979 Committee: Emilio Zamora, Supervisor Toyin Falola Anne Martinez Harry Cleaver Louis Mendoza “From Below and To the Left”: Re-Imagining the Chicano Movement through the Circulation of Third World Struggles, 1970-1979 by Alan Eladio Gómez, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2006 For the Zarate, González, Gallegos, and Gómez families And for my father, Eladio Gómez Well, we’ve had to look at ourselves, we have had to look at our history: actually we have had to define that history because it was never defined by North American historians. Antonia Castañeda Shular, Seattle, 1974 “El mismo enemigo ha querido mutilar, y si posible, hacer desaparecer nuestras culturas, tan parecidas una a la otra, y sin embargo, tanto el Chicano como el Boricua hemos podido salvar nuestra idenitidad cultural…” Rafael Cancel Miranda, Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, 1972 “Prison is a backyard form of colonialism” raúlrsalinas “Nuestra América” José Martí Por la reunificación de los Pueblos Libres de América en su Lucha el Socialismo. Partido de los Pobres Unido de América (PPUA) “Somos uno porque América es una.” Centro Libre de Expresión Teatral Artística (CLETA) Exploitation and oppression transcend national boundaries and so the success of our resistance will be largely dependent upon our ability to forge strong ties with struggling peoples across the globe. -

Voices of Feminism Oral History Project: Martinez, Betita

Voices of Feminism Oral History Project Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Northampton, MA ELIZABETH (BETITA) MARTINEZ interviewed by LORETTA ROSS March 3, 2006, Atlanta, GA August 6, 2006, Oakland, CA This interview was made possible with generous support from the Ford Foundation. © Sophia Smith Collection 2006 Voices of Feminism Oral History Project Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Narrator Elizabeth (Betita) Martinez was born December 12, 1925. As the child of a dark-skinned Mexican-born father and a white Euro-American mother, Betita met discrimination as she was growing up in segregated Washington, D.C. During World War II, Martinez attended Swarthmore College, where she was the only non- white student on campus. After graduation in 1946, she worked at the newly-established United Nations, where she researched decolonization efforts and strategies. In the late 1950s she became an editor at Simon & Schuster, and later Books and Arts Editor of The Nation magazine. She also became active in the U.S. civil rights movement, directing the New York office of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and participating in SNCC’s Freedom Summer in Mississippi in 1964. From 1968 to 1976, Martinez lived in New Mexico where she became founding editor of El Grito del Norte (The Cry of the North), a monthly community newspaper that linked the Chicano land movement to similar struggles around the world. She served as founding director of the Chicano Communications Center in Albuquerque to teach Chicanos about history and contemporary issues. After moving to California in 1976, Martinez joined the Democratic Workers Party, a Marxist group led by women, and became involved in Central American solidarity work, local struggles for social justice, and grassroots organizing to save public services. -

Barbara Carrasco Interviewed by Karen Mary Davalos on August 30, September 11 and 21, and October 10, 2007

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 3, NOVEMBER 2013 BARBARA CARRASCO INTERVIEWED BY KAREN MARY DAVALOS ON AUGUST 30, SEPTEMBER 11 AND 21, AND OCTOBER 10, 2007 Artist and muralist Barbara Carrasco lives and works in Los Angeles. She received her BFA from UCLA and her MFA from California Institute of the Arts. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America. Carrasco has taught at UC Riverside, UC Santa Barbara, and Loyola Marymount University and is the recipient of a number of fellowships and grants. Her papers are held in the Department of Special Collections at Stanford University and the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Karen Mary Davalos is chair and professor of Chicana/o studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research interests encompass representational practices, including art exhibition and collection; vernacular performance; spirituality; feminist scholarship and epistemologies; and oral history. Among her publications are Yolanda M. López (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008); “The Mexican Museum of San Francisco: A Brief History with an Interpretive Analysis,” in The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971–2006 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010); and Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (University of New Mexico Press, 2001). This interview was conducted as part of the L.A. Xicano project. Preferred citation: Barbara Carrasco, interview with Karen Mary Davalos, August 30, September 11 and 21, and October 10, 2007, Los Angeles, California. CSRC Oral Histories Series, no. 3. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2013. -

Stop the Racist Attacks' '

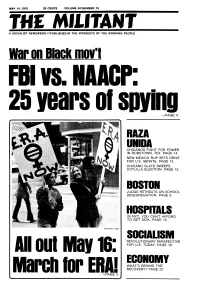

MAY 14, 1976 25 CENTS VOLUME 40/NUMBER 19 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE • • - --PAGE 4 RAZA u CHICANOS FIGHT FOR POWER IN ROBSTOWN, TEX. PAGE 14. NEW MEXICO RUP SETS DRIVE FOR U.S. SENATE. PAGE 15. CHICANO SLATE SWEEPS COTULLA ELECTION. PAGE 15. JUDGE RETREATS ON SCHOOL DESEGREGATION. PAGE 6. HOSPITALS IN NYC, YOU CAN'T AFFORD TO GET SICK. PAGE 13. Militant/Stu Singer ALISM REVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE • FOR U.S. TODAY. PAGE 16 . • ECO y WHAT'S BEHIND THE I RECOVERY? PAGE 23 . -PAGE• 3 In Brief THIS GAY CENTER HIT BY ARSON: Eleven days after the SECRET FILES TIP THE SCALES: Have you ever been WEEK'S Supreme Court upheld state laws prohibiting homosexual rejected from jury duty? Is there an FBI file on you? If the acts between consenting adults, Seattle's Gay Community answer is yes to both questions, there could be a connection. MILITANT Center was destroyed by fire. This was the second arson Federal prosecutors recently admitted that FBI and police attack in two weeks. 3 March for women's rights files are sometimes checked when juries are being selected David Neth, the center's director, told the Militant that in Springfield May 16! for "important and sensitive Government prosecutions," there has been a recent increase in threatening phone calls reported the April 19 New York Times. Prosecutors secretly 4 FBI admits to the center and bomb threats at gay bars. "The court's check these and Internal Revenue Service files to uncover spying on NAACP ruling obviously has encouraged violence by an antigay "possible antigovernment biases" among prospective jurors. -

Benefit Concert for Olga Talamante

Benefit concert for Olga Talamante February 12, 1976 A benefit concert for Olga Talamante - 26-year-old Chicana from Gilroy, California, who is the only U.S. citizen imprisoned in Argentina - will be held at 8 p.m. Friday, Feb. 20, in the Revelle Cafeteria, at the University of California, San Diego. Talamante, who has been in prison for 13 months, is an honors graduate of the University of California, Santa Cruz. She was teaching English in the city of Azul when she was arrested in November 1974, under the special state of siege laws imposed by President Isabel Peron and the Argentine government. She and several young Argentinians were convicted last September of being present in a home where subversive literature was found. Shortly after her arrest, there were reports that Talamante would be deported but, since she is now appealing her conviction, all talk of deportation appears to have stopped. Her legal counsel, civil rights attorney Leonard Weinglass, who traveled to Azul to investigate Talamante's reports that she had been tortured when arrested and to discover why there had been little action on the part of the U.S. government, claims to have substantiated the young woman's allegations. Talamante's plight has become a cause celebre in the San Francisco Bay area, not just among Chicanos but with feminists and other political activists. Some Bay area newspapers refer to her simply as "Olga." No small influence in focusing attention on the case have been Talamante's poignant letters from prison. National columnist Jack Anderson refers to her as "an American Anne Frank." According to the State Department, U.S. -

The Rag Table of Contents

The Rag Table of Contents Compiled by Phil Prim This Table of Contents was entered into a database by Hunter Ellinger before the August 2005 Rag Reunion. Through online access, Rag staffers made several updates. Year Page 1966 10 Issues 2 1967 28 Issues 4 1968 41 Issues 9 1969 30 Issues 16 1970 42 Issues 22 1971 37 Issues 30 1972 39 Issues 38 1973 39 Issues 46 1974 41 Issues 54 1975 33 Issues 62 1976 20 Issues 69 1977 6 Issues 73 The Rag Table of Contents: 1966 Page 14: Terminex Bug 10 Issues Page 16: Rag benefit (Gilbert Shelton) [updated] The Rag - Summary of 10/10/1966 Issue The Rag - Summary of 10/31/1966 Issue Page 1: The truth is "beep: on page ... (Carol Page 1: Women sit in at Selective Service office Neiman) (Thorne Dreyer) Page 1: General John Economidy (Kaye Page 4: Gentle Thursday announcement Northcott) Page 5: Student assembly (Jeff Shero) Page 3: United front against fascism (Bobby Page 8: U and I Hamburger Seale) Page 9: Stanford Greeks (Larry Freudiger) Page 4: Playboy morality (Jeff Shero) [updated] Page 5: Nixonese and English Page 12: Woman mourns dead sons (Jude Page 5: Graphic (Clelie Moore) Binder) Page 6: The Bent Spokesman (Michael Page 13: Woman's letter to Selective Service Beaudette) [updated] System Page 7: Lee Otis Johnson Page 14: The draft (Gary Thiher) Page 8: Poem and graphic Page 17: Ken Kesey (Larry Freudiger) Page 9: Review, Who Isn't Afraid of Virginia Page 21: Records (Kirk Wilson) Woolf? (Gary Chason) [updated] Page 24: MacBird (Thorne Dreyer) [updated] The Rag - Summary of 10/17/1966 Issue The -

THE GREENLINING INSTITUTE Advocacy | Research | Leadership Development the GREENLINING INSTITUTE Annual Report 2010

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 THE GREENLINING INSTITUTE Advocacy | Research | Leadership Development THE GREENLINING INSTITUTE Annual Report 2010 Board of Directors Greenlining Coalition George Dean, Co-Chair Allen Temple Baptist Church KHEIR Center Ortensia Lopez, Co-Chair American GI Forum La Maestra Family Clinic David Glover, Secretary Asian Business Association Latino Business Chamber of Greater Los Angeles Robert Apodaca, Treasurer Black Business Association Mexican American Grocers Association Jorge Corralejo Black Economic Council Mexican American Political Association Rosario Anaya California Black Chamber of Commerce Mission Language and Vocational School Alfred Fraijo California Hispanic Chambers of Commerce NaFFAA Yusef Freeman California Journal for Filipino Americans National Asian American Coalition Darlene Mar California Rural Legal Assistance Oakland Citizens Committee for Urban Renewal (OCCUR) Louise Perez CHARO Community Development Corporation Our Weekly Mark Rutledge Chicana/Latina Foundation San Francisco African American Chamber of Commerce Olga Talamante Chicano Federation, San Diego San Francisco Housing Development Corporation Founding Emeritus Board Community Resource Project, Inc. Search to Involve Pilipino-Americans Council of Asian American Business Associations Southeast Asian Community Center Ralph Abascal Economic Business Development, Inc. The East Los Angeles Community Union (TELACU) Leo Avila El Concilio of San Mateo County Ward Economic Development Corporation Ben Benavidez First AME Church, Los Angeles West -

H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol

2014 Roundtable Editors: Diane Labrosse and Dustin H-Diplo Walcher Roundtable and Web Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review h-diplo.org/roundtables Commissioned for H-Diplo by Dustin Walcher Volume XVI, No. 9 (2014) 27 October 2014 Introduction by Dustin Walcher William Michael Schmidli. The Fate of Freedom Elsewhere: Human Rights and U.S. Cold War Policy Toward Argentina. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013. ISBN: 978-0-8014-5196-6 (hardcover, $39.95). URL: http://www.tiny.cc/Roundtable-XVI-9 or http://h-diplo.org/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XVI-9.pdf Contents Introduction by Dustin Walcher, Southern Oregon University ................................................ 2 Review by Jason Colby, University of Victoria .......................................................................... 5 Review by David M. K. Sheinin, Trent University ...................................................................... 9 Review by Bradley Simpson, University of Connecticut ......................................................... 12 Author’s Response by William Michael Schmidli, Bucknell University ................................... 17 © 2014 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. XVI, No. 9 (2014) Introduction by Dustin Walcher, Southern Oregon University uestions as to the motives underlying U.S. foreign policy have long lay at the heart of the field of foreign relations history. Historians consistently weigh the relative Qimport of the search for security, economic self-interest, domestic culture, ideology, and other factors in the policymaking process. In those discussions, the desire to expand human rights abroad rarely emerges as an end in itself. As Michael Schmidli explains, although the concept of ‘human rights’ was very much a product of particular political discourses, the promotion of human rights became an important objective for the Jimmy Carter administration. -

MOVEMENTS, MOVIMIENTOS, and MOVIDAS María Cotera, Maylei Blackwell, and Dionne Espinoza

Espinoza_6886_3pp IntroduCtIon MOVEMENTS, MOVIMIENTOS, AND MOVIDAS María Cotera, Maylei Blackwell, and Dionne Espinoza We have not one movement but many. Our political, literary, and artistic movements are discarding the patriarchal model of the hero/leader leading the rank and file. Ours are individual and small group movidas, unpublicized movimientos—movements not of media stars or popular authors but of small groups or single mujeres, many of whom have not written books or spoken at national conferences. —glorIa anzaldúa, Making Face/Making Soul The 1960s and 1970s were times of great political upheaval and social transforma- tion across the globe. During this period, Mexican American youth in the United States developed a new and powerful form of political consciousness they called “Chicanismo.” Part of a worldwide youth revolt in the 1960s, their calls for “Chi- cano liberation” responded to economic inequality, everyday and institutional racism, and the increasingly militant struggle to end the Vietnam War. Within mass-based organizations, through murals and artistic practices, in community- based organizations or small consciousness-raising groups, Chicanas were on the front lines of forging these new cultures of rebellion. Women played significant roles in the major mobilizations and organizations that coalesced into what is now understood historiographically as the Chicano movement era, including both well-known movement formations—like the United Farm Workers, the Crusade for Justice, the land grant movement, and La Raza Unida Party—and numerous regional and national initiatives. Moving within and between multiple sites of struggle, they challenged conventional notions of oppositional subjectiv- ity and created their own, specifically Chicana, praxis of resistance.