Rita Sanchez: an Oral Interview Conducted by Rudy P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master's

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Jerónimo Arellano, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Sarah Mabry August 2018 Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Copyright by Sarah Mabry © 2018 Dedication Here I acknowledge those individuals by name and those remaining anonymous that have encouraged and inspired me on this journey. First, I would like to dedicate this to my great grandfather, Jerome Head, a surgeon, published author, and painter. Although we never had the opportunity to meet on this earth, you passed along your works of literature and art. Gleaned from your manuscript entitled A Search for Solomon, ¨As is so often the way with quests, whether they be for fish or buried cities or mountain peaks or even for money or any other goal that one sets himself in life, the rewards are usually incidental to the journeying rather than in the end itself…I have come to enjoy the journeying.” I consider this project as a quest of discovery, rediscovery, and delightful unexpected turns. I would like mention one of Jerome’s six sons, my grandfather, Charles Rollin Head, a farmer by trade and an intellectual at heart. I remember your Chevy pickup truck filled with farm supplies rattling under the backseat and a tape cassette playing Mozart’s piano sonata No. 16. This old vehicle metaphorically carried a hard work ethic together with an artistic sensibility. -

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Online items available Guide to the Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 (805) 893-8563 [email protected] © 2006 Guide to the Centro Cultural de la CEMA 12 1 Raza Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet(153 document boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 13 slide albums, 229 posters, and 975 online items)Online items available Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes).Online items available creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Access Restrictions None. -

Editors' Introduction: New Dimensions in the Scholarship and Practice Of

Editors’ Introduction 1 Editors’ Introduction: New Dimensions in the Scholarship and Practice of Mexican and Chicanx Social Movements Maylei Blackwell & Edward J. McCaughan* HIS SPECIAL ISSUE OF SOCIAL JUSTICE BRINGS TOGETHER THE WORK OF SCHOLARS and activists from Mexico and the United States, representing a variety of disciplines and movements, to discuss current trends in the scholarship Tand practices of Mexican and Chicanx1 social movements. The idea to organize a forum to share and critically assess new developments in the social movements of “Greater Mexico” came to the editors in the summer of 2010. Maylei Blackwell, Ed McCaughan, and Devra Weber crossed paths in Oaxaca, Mexico, that summer. Blackwell was helping to lead a workshop on issues of gender and sexuality with an indigenous community affiliated with the Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales. McCaughan was there completing his manuscript on art and Mexican/ Chicanx social movements, and Weber had been invited to present her research on the Partido Liberal Mexicano for a symposium commemorating the centennial of the Mexican Revolution. As we shared our work and observations about significant political and cultural developments in the social activism of Mexican communities on both sides of the border, we felt compelled to organize a forum in which activists and scholars could reflect on these changes. A great deal has changed—economically, politically, culturally, and intellectu- ally—in the decades since the watershed 1968 Mexican student movement, the historic Chicanx mobilizations of the 1960s and 1970s, and the internationally celebrated EZLN uprising of 1994. Moreover, 25 years have passed since publica- tion of the last English-language anthology to bring together research on a wide variety of Mexican social movements (Foweraker and Craig 1990). -

A Selection of Chicano Studies Resources on the Web

A Selection of Chicano Studies Resources on the Web Azteca http://www.azteca.net/aztec/ Information accumulated especially for Mexicans, Chicanos, and/or Mexican-Americans Bibliography of Chicana/Chicano Literature http://www.sdmesa.edu/library/docs/gonzalez.html An online bibliography related to Mexican-American literature with references to Mesa, City and Miramar library holdings. La Bloga: Chicano Literature, Chicano Writers, Chicano Fiction, News, Views, Reviews http://labloga.blogspot.com/ An award-winning web log with links to informative and reliable websites about Chicano/Chicana Literature. Brief History of Chicano Murals http://www.sparcmurals.com/present/cmt/cmt.html Sponsored by the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), an organization that sponsors, preserves, and documents public art. Chicano Art Digital Image Collection http://cemaweb.library.ucsb.edu/digitalArchives.html A representative sampling of the cataloged archival images in Chicano visual arts in the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives (CEMA) at UC Santa Barbara. Chicano.org http://chicano.org Chicano-focused news, editorials, and entertainment, with links to Chicano websites. Chicanos Online http://www.asu.edu/lib/archives/chiclink.htm A list of sites dealing with Chicano issues provided by the University of Arizona. Cinco de Mayo http://www.nacnet.org/assunta/spa5may.htm Bilingual (English and Spanish) account of the events that occurred during the Battle of Puebla, Mexico, on May 5, 1862, and why this day is important to Mexican-Americans. Includes bibliography at end of article. Cinco de Mayo: A Celebration of Mexican Heritage http://www2.worldbook.com/features/cinco/html/cinco.htm Contains articles on the history of Mexico, modern life and culture in Mexico, and general information on Hispanic Americans. -

Ralph Maradiaga Collection CEMA 35

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8639rd9 No online items Guide to the Ralph Maradiaga collection CEMA 35 Finding aid prepared by Mari Khasmanyan, 2015. UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2015 October 26 Guide to the Ralph Maradiaga CEMA 35 1 collection CEMA 35 Title: Ralph Maradiaga collection Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 35 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 22.1 linear feet(4 document boxes, 3 binder boxes, 2 oversized boxes, 165 posters, 41 audio recordings, and 150 video recordings). Date (bulk): Bulk, 1973-1983 Date (inclusive): 1963-1993 Abstract: The Ralph Maradiaga Collection covers Maradiaga's educational, professional and creative accomplishments. They are recorded in exhibit materials, poetry, posters and other papers. Many slides and photos are part of this collection as well. The photos cover much of his personal and professional life as an artist. Included are also numerous audio and video recordings. These recordings cover his extensive involvement in filmmaking as a producer and director. Physical Location: Del Norte (Boxes 1-7), Del Norte Oversized (Boxes 8-9), Del Norte map case (posters). There are some videos from this collection that are available for streaming online, links are provided in the video section. Language of Materials: The collection is predominantly in English, with some Spanish materials. creator: Maradiaga, Ralph Access Restrictions Collection is open for research. -

Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals a National Register Nomination

CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION Josie S. Talamantez B.A., University of California, Berkeley, 1975 PROJECT Submitted in partial satisfaction of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY (Public History) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2011 CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION A Project by Josie S. Talamantez Approved by: _______________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Lee Simpson _______________________________, Second Reader Dr. Patrick Ettinger _______________________________ Date ii Student:____Josie S. Talamantez I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and this Project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the Project. ______________________, Department Chair ____________________ Aaron Cohen, Ph.D. Date Department of History iii Abstract of CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION by Josie S. Talamantez Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals Chicano Park is a 7.4-acre park located in San Diego City’s Barrio Logan beneath the east-west approach ramps of the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge where the bridge bisects Interstate 5. The park was created in 1970 after residents in Barrio Logan participated in a “takeover” of land that was being prepared for a substation of the California Highway Patrol. Barrio Logan the second largest barrio on the West Coast until national and state transportation and urban renewal public policies, of the 1950’s and 1960’s, relocated thousands of residents from their self-contained neighborhood to create Interstate 5, to rezone the area from residential to light industrial, and to build the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge. -

Barrio Logan Trolley Station

REGIONAL MOBILITY HUB IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY Barrio Logan Trolley Station Mobility hubs are transportation centers located in smart growth areas served by high frequency transit service. They provide an integrated suite of mobility services, amenities, and technologies that bridge the distance between transit and an individual’s origin or destination. They are places of connectivity where different modes of travel—walking, biking, transit, and shared mobility options—converge and where there is a concentration of employment, housing, shopping, and/or recreation. This profile sheet summarizes mobility conditions and demographic characteristics around the Barrio Logan Trolley Station to help inform the suite of mobility hub features that may be most suitable. Barrio Logan is one of San Diego’s oldest and most culturally significant neighborhoods and job centers. The community is located south of Downtown San Diego and is adjacent to San Diego Bay’s bustling maritime industry. The Barrio Logan Trolley Station offers residents and employees connections to local restaurants and retailers, Chicano Park, and the San Diego Continuing Education César E. Chávez Campus. The station provides access to the UC San Diego Blue Line and a high frequency, late operating local bus route. The map below depicts the transit services, bikeways, and shared mobility options anticipated to serve the community in 2020. 2020 MOBILITY SERVICES MAP In 2020, a variety of travel options will be available within a five minute walk, bike, or drive to the Barrio Logan -

Greenlining's 25Th Annual Economic Summit

510.926.4001 tel The Greenlining Institute 510.926.4010 fax The Greenlining Institute Oakland, California @Greenlining GREENLINING’S 25TH ANNUAL ECONOMIC SUMMIT www.greenlining.org @Greenlining e come together for The Greenlining Institute’s 26th annual Economic Summit at a moment that feels special and pivotal. On the one hand, we face continuing attacks on communities of color and on others who are too often marginalized in this Wsociety. But in 2018, we saw that people of color will no longer just play defense against attacks on our rights; we will lead America toward a vision of equity and justice. That’s why this year’s Summit theme takes its inspiration from the words of Representative Maxine Waters – that famous “reclaiming my time” moment that so quickly went viral – in order to highlight the leaders, especially here in California, who refuse to stay silent in the face of injustice. We invite you to listen and be inspired by such stellar figures as Representative Barbara Lee, our Lifetime Achievement Award winner, California Public Utilities Commissioner Martha Guzman Aceves, She The People founder Aimee Alison, Dream Corps President Vien Truong, and acclaimed rapper, activist, producer, screenwriter and film director Boots Riley, among many others. But we also hope you’ll join our interactive Equity Lab in the afternoon and explore practical tools to move the struggle for justice and equity from thinking to doing. And today we will also be saying a very special farewell to Orson Aguilar as he transitions out of Greenlining after 11 years as our President. Orson first came to Greenlining through our Leadership Academy as a young leader more than 20 years ago. -

SI Calendar June20updated

2017 MALCS Summer Institute – Final Draft 06.27.2017 *Tuesday, July 18. Board Meeting. 9:00am-5:00pm Wednesday July 19, 2017 [EC/CC Meeting (if needed): 9:00am-12:00pm] Pre-Institute Professional, Emotional Well-Being, and Academic Workshops *Pre-Registration Required for Workshops A1-2, and B1-2. (Email At-Large Representative Dr. Sandra M. Pacheco [email protected] to register) 9am-12pm A1. Demystifying Academic Writing with Dr. Wanda Alarcon Writing is hard. The reasons are not always mechanical yet it helps to have an understanding of some of the forms in which undergraduate and graduate students are expected to write. The goals of this workshop include: introduction to academic genres; a discussion on revision; handy tips to strengthen writing. This writing workshop is geared toward undergrads and graduate students. Workshop is limited to 16 participants. A2. Healing Workshop: Remedios y Rituales Curanderas sin Fronteras will provide an interactive workshop where participants will learn how to make different remedios they can take home. The focus will be on hierbas and remedios for stress and protection. There is a small sliding scale fee of $10-$15 for materials. Limited to 20 participants. 1pm-4pm B1. Creating a Rhythm and Schedule for your Writing with Dr. Cindy Cruz Advanced grad students, post docs, and early career faculty are invited to participate in a pre-institute workshop on writing time management. Participants will: • Build skills on writing time management in academia • Learn about embodied decolonial practice, and negotiating time, research, teaching, and service • Centralize the epistemology of the "Brown" body, Person of Color, and Queer Person of Color, to help us see the body as a site of knowledge to frame agency in academia. -

Copyright by Alan Eladio Gómez 2006

Copyright by Alan Eladio Gómez 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Alan Eladio Gómez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “From Below and to the Left”: Re-Imagining the Chicano Movement through the Circulation of Third World Struggles, 1970-1979 Committee: Emilio Zamora, Supervisor Toyin Falola Anne Martinez Harry Cleaver Louis Mendoza “From Below and To the Left”: Re-Imagining the Chicano Movement through the Circulation of Third World Struggles, 1970-1979 by Alan Eladio Gómez, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2006 For the Zarate, González, Gallegos, and Gómez families And for my father, Eladio Gómez Well, we’ve had to look at ourselves, we have had to look at our history: actually we have had to define that history because it was never defined by North American historians. Antonia Castañeda Shular, Seattle, 1974 “El mismo enemigo ha querido mutilar, y si posible, hacer desaparecer nuestras culturas, tan parecidas una a la otra, y sin embargo, tanto el Chicano como el Boricua hemos podido salvar nuestra idenitidad cultural…” Rafael Cancel Miranda, Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, 1972 “Prison is a backyard form of colonialism” raúlrsalinas “Nuestra América” José Martí Por la reunificación de los Pueblos Libres de América en su Lucha el Socialismo. Partido de los Pobres Unido de América (PPUA) “Somos uno porque América es una.” Centro Libre de Expresión Teatral Artística (CLETA) Exploitation and oppression transcend national boundaries and so the success of our resistance will be largely dependent upon our ability to forge strong ties with struggling peoples across the globe. -

The Place of Chicana Feminism and Chicano Art in the History

THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Beatriz Anguiano FALL 2012 © 2012 Beatriz Anguiano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM A Project by Beatriz Anguiano Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Chloe S. Burke __________________________________, Second Reader Donald J. Azevada, Jr. ____________________________ Date \ iii Student: Beatriz Anguiano I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Chair ___________________ Mona Siegel, PhD Date Department of History iv Abstract of THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM by Beatriz Anguiano Statement of Problem Chicanos are essentially absent from the State of California United States History Content Standards, as a result Chicanos are excluded from the narrative of American history. Because Chicanos are not included in the content standards and due to the lack of readily available resources, this presents a challenge for teachers to teach about the role Chicanos have played in U.S. history. Chicanas have also largely been left out of the narrative of the Chicano Movement, also therefore resulting in an incomplete history of the Chicano Movement. This gap in our historical record depicts an inaccurate representation of our nation’s history. -

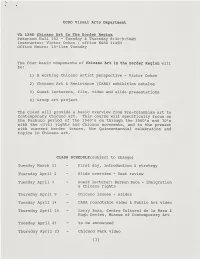

UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art

- UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art In The Border Region Peterson Hall 102 - Tuesday & Thursday 8:30-9:50AM Instructor: Victor Ochoa / office H&SS 1145D Office Hours: 10-11am Tuesday The four basic components of Chicano Art in the Border Region will be: 1) A working Chicano artist perspective - Victor Ochoa 2) Chicano Art & Resistance (CARA) exhibition catalog 3) Guest lecturers, film, video and slide presentations 4) Group art project The class will provide a basic overview from Pre-Colombian art to Contemporary Chicano art. This course will specifically focus on the Pachuco period of the 1940's on through the 1960's and 70's with the civil rights and Chicano movements, and to the present with current border issues, the Quincentennial celebration and topics in Chicana art. CLASS SCHEDULE(subject to change) Tuesday March 31 First day, introduction & strategy Thursday April 2 Slide overview - Text review Tuesday April 7 Guest lecturer: Herman Baca - immigration & Chicano rights Thursday April 9 - Chicano issues - slides Tuesday April 14 - CARA roundtable video & Public Art video Thursday April 16 - Larry Baza, Centro Cultural de la Raza & Hugh Davies, Museum of Contemporary Art Tuesday April 21 - to be announced Thursday April 23 - Chicano Park video [1] VA 128D(cont.) Saturday April 25 - Chicano Park Day - required field trip Tuesday April 28 - Issac Artenstein - "Mi Otro Yo" & video potpourri Thursday April 30 - Ireina Cervantes: personal work, Chicanas & Frida (Midterm due) Tuesday May 5 - David Avalos & BAW/TAF the