The Rhetoric of Lowriding: a Misunderstood Cultural Movement in the Public Realm."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME Chicano Studies Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 119 923 ric 009 066 AUTHOR Marquez, Benjamin, Ed. TITLE Chicano Studies Bibliography: A Guide to the Resources of the Library at the University of Texas at El Paso, Fourth Edition. INSTITUTION Texas Univ., El Paso. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 138p.; For related document, see ED 081 524 AVAILABLE PROM Chicano Library Services, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79902 ($3.00; 25% discount on 5 or more copies) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$7.35 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; *Bibliographies; Books; Films; *library Collections; *Mexican Americans; Periodicals; *Reference Materials; *University Libraries IDENTIFIERS Chicanos; *University of Texas El Paso ABSTRACT Intended as a guide to select items, this bibliography cites approximately 668 books and periodical articles published between 1925 and 1975. Compiled to facilitate research in the field of Chicano Studies, the entries are part of the Chicano Materials Collection at the University of Texas at El Paso. Arranged alphabetically by the author's or editor's last name or by title when no author or editor is available, the entries include general bibliographic information and the call number for books and volume number and date for periodicals. Some entries also include a short abstract. Subject and title indices are provided. The bibliography also cites 14 Chicano magazines and newspapers, 27 audiovisual materials, 56 tape holdings, 10 researc°1 aids and services, and 22 Chicano bibliographies. (NQ) ******************************************14*************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. -

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master's

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Jerónimo Arellano, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Sarah Mabry August 2018 Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Copyright by Sarah Mabry © 2018 Dedication Here I acknowledge those individuals by name and those remaining anonymous that have encouraged and inspired me on this journey. First, I would like to dedicate this to my great grandfather, Jerome Head, a surgeon, published author, and painter. Although we never had the opportunity to meet on this earth, you passed along your works of literature and art. Gleaned from your manuscript entitled A Search for Solomon, ¨As is so often the way with quests, whether they be for fish or buried cities or mountain peaks or even for money or any other goal that one sets himself in life, the rewards are usually incidental to the journeying rather than in the end itself…I have come to enjoy the journeying.” I consider this project as a quest of discovery, rediscovery, and delightful unexpected turns. I would like mention one of Jerome’s six sons, my grandfather, Charles Rollin Head, a farmer by trade and an intellectual at heart. I remember your Chevy pickup truck filled with farm supplies rattling under the backseat and a tape cassette playing Mozart’s piano sonata No. 16. This old vehicle metaphorically carried a hard work ethic together with an artistic sensibility. -

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

Second Generation

HISTORY The New Mexican-Americans in Wartime America: riots reflect the state of the Mexican American pop How the "Z-Oot Suit Riots" and the "Second Generation" events shape the future of the Mexican American c Transformed Mexican-American Ethnic Politics Brady Dvorak In this paper, l will show how the unique state oft especially the first US-born generation of Mexican Abstract second generation) - coupled with the anxiety of\ This paper looks at the unique demographic, economic, and cultural state of ethnic Mexicans living of racial tensions in Los Angeles. And, I will sho\\ in the United States during World War II and how the "Zoot Suit Riots" both refl ected the wartime riots" created by the sensationalistic press affected ethnic relations between Latinos and Anglos and influenced the future of Mexican American civil campaign in two ways: (1) Popular interpretation< rights movements. In particular, the riots will be examined within the context of the emergence of a American youth, bridging a correlation between et pachuco youth culture within the second generation of US-born ethnic Mexicans. Newspaper there being any racial discrimination during the ric articles of the time and complimentary research will also show how popular public perception of perception of there being no racial element of disc the events affected the way in which Mexican American community leaders would negotiate the communities. With Mexican American activists or ethnic politics of civil rights until the 1960s. anti-Mexican sentiment, they preached uncompror while ignoring the more complex problems of disc Introduction disparity between Latinos and Anglos in the Unite ne of the most notorious episodes in the history of US ethnic relations, and certainly in Mexican Americans, Pachucos, and World 0 Mexican American history, was the so called "zoot suit riots" that took place in wartime Los Angeles. -

News Nepantla

UCSB Chican@ Studies Newsletter, Fall 2010, No. 3 News Nepantlfrom a LITERARY GREATS VISIT UCSB The 8th annual Luis Cisneros’s Leal Award for forthcoming book, Distinction in Writing in Your Chicano/Latino Pajamas. She Literature was introduced selected awarded on October readings from the 28, 2010 to Jimmy work‐in‐progress Santiago Baca. with comments on Named after her community Professor Luis Leal service work, who died in early encouraging 2010 at the age of everyone to pick up a 102 and who was pen and paper and one of the pioneers engage the art of in the study of literature. ‘Write the Chicano literature, first draft as if you the award honors a Jimmy Santiago Baca and Sandra Cisneros give talks co‐sponsored by the are talking to your writer on Chicano/ Department of Chican@ Studies. best friend. Latino subjects who Completely honest. literacy and of writing and has Her slippers shuffling across has achieved national and Like you were comfortable become one of the major the stage, Sandra Cisneros international acclaim through talking to them even wearing poets and writers in the approached the podium in a substantial body of work. pajamas.’ United States. bright blue pajamas sporting Jimmy Santiago Baca, a The audience was Baca has written more than multi‐colored polka dots. native of New Mexico, is a enthralled as Cisneros read a eleven volumes of poetry. In Hundreds of students powerful and courageous short story following the 2001 he published his accompanied by community voice as a poet, short story narrator through her gripping and powerful members (one stating in the writer, memoir writer, community in search of both a autobiography A Place to Q&A session that he traveled essayist, and novelist. -

Justice and Injustice in Three Mexican-American Playwrights

MAN'S INHUMANITY TO MAN: JUSTICE AND INJUSTICE IN THREE MEXICAN-AMERICAN PLAYWRIGHTS by JOSHUA AL MORA, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN • SPANISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted Dean of the Graduate School December, 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this time to thank the members of my dissertation committee: Dr. Janet Perez, Dr. Harley Oberhelman, Dr. Wendell Aycock and Dr. Roberto Bravo. A special thanks goes out to Dr. P6rez who worked very closely with me and spent many hours reading and editing my dissertation. A special note of thanks goes out to all of my committee members for their belief in me and their inspiration during what have been the most difficult times of my life. Thank you for offering your help and for all you did. A special thank you also to the Department of Classical and Modern Languages at Texas Tech University and the faculty and staff for all of your support and encouragement. Esta obra va dedicada a mi padre, que en paz descanse, y a mi madre quienes con mucha paciencia esperaron que yo terminara. Gracias a su fe y sus oraciones se cumplib esta obra. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE ROOTS OF CHICANO AND OTHER TERMS 40 III. THE WAR IN THE FIELDS 72 IV. THE STRUGGLE TO ENTER THE UNITED STATES 113 V. IN SEARCH OF RESPECT IN THE SCHOOLS 148 VI. -

Borderlands of the Rio Grande Valley: Where Two Worlds

BORDERLANDS OF THE RIO GRANDE VALLEY: WHERE TWO WORLDS BECOME ONE by Nora Lisa Cavazos, M.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in International Studies August 2014 Committee Members: Paul Hart, Chair John McKiernan-Gonzalez Robert Gorman COPYRIGHT by Nora Lisa Cavazos 2014 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public law94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As copyright holder of this work I, Nora Lisa Cavazos authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would sincerely like to thank my family for inspiring me to write about the reality of such a complicatedly beautiful place. Without the love and support from my Mom, Dad, Linda, Melissa, David, Noah, and Jaeden, none of this would have been possible. For all the times they extended their home, their food, and their stress relieving techniques, I am undoubtedly thankful. A big thank you to Dr. Paul Hart, Dr. John McKiernan-Gonzalez, and Dr. Robert Gorman for encouraging my study of the Rio Grande Valley, the place I love the most, and for pushing me beyond what I knew I was capable of. -

San Diego County Board of Education Paulette Donnellon • Guadalupe González • Alicia Muñoz • Mark Powell • Rick Shea

San Diego County Board of Education Paulette Donnellon • Guadalupe González • Alicia Muñoz • Mark Powell • Rick Shea Dr. Paul Gothold San Diego County Superintendent of Schools Tracy E. Thompson, Executive Director Juvenile Court and Community Schools 6401 Linda Vista Road, San Diego, CA 92111 | www.sdcoe.net | 858-292-3500 ©2020 SDCOE Please note that there may be grammatical errors,etc., but since this is narrative writing, we chose not to edit them in order to retain an authentic student voice. The Storytellers | 1 What What a strong, independent, resilient women Victoria J. (Urban Camp GRF) Momma Bear Momma bear protects baby from lion Victoria J. (Urban Camp GRF) Gymnastics is Life Sam loved and lived for gymnastics Victoria J. (Urban Camp GRF) Care Mama bear will protect her cub Ruby B. (Urban Camp GRF) Be Be fair, be strong, be independent Ruby B. (Urban Camp GRF) Bored Emily is jumping because she’s bored Nicole C. (Urban Camp GRF) Grizzly Bears Big and brown, splinters, and hospitalized La’Ney M. (Urban Camp GRF) Excitement It’s the weekend, sunny day, excitement La’Ney M. (Urban Camp GRF) The Notorious RBG Notorious RBG was an incredible judge Dianna J. (Urban Camp GRF) Big Bears Baby bear and mama bear are relaxing Dianna J. (Urban Camp GRF) 2 | The Storytellers Almost Flying Joselin, jumping of joy almost flying Cassandra O. (Urban Camp GRF) Jump Jasmine jumped up to the sky! Alissa C. (Urban Camp GRF) Single Mother Dad left mom stayed later died Aaliyah P. (Urban Camp GRF) Rest Easy Strong-willed determined fighter rest easy Aaliyah P. -

El Paso and the Twelve Travelers

Monumental Discourses: Sculpting Juan de Oñate from the Collected Memories of the American Southwest Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV – Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften – der Universität Regensburg wieder vorgelegt von Juliane Schwarz-Bierschenk aus Freudenstadt Freiburg, Juni 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Udo Hebel Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Volker Depkat CONTENTS PROLOGUE I PROSPECT 2 II CONCEPTS FOR READING THE SOUTHWEST: MEMORY, SPATIALITY, SIGNIFICATION 7 II.1 CULTURE: TIME (MEMORY) 8 II.1.1 MEMORY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 9 II.2 CULTURE: SPATIALITY (LANDSCAPE) 13 II.2.1 SPATIALITY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 14 II.3 CULTURE: SIGNIFICATION (LANDSCAPE AS TEXT) 16 II.4 CONCEPTUAL CONVERGENCE: THE SPATIAL TURN 18 III.1 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: PLACE – SPACE – LANDSCAPE III.1.1 PLACE 21 III.1.2 SPACE 22 III.1.3 LANDSCAPE 23 III.2 EMPLACEMENT AND EMPLOTMENT 25 III.3 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: SITE – MONUMENT – LANDSCAPE III.3.1 SITES OF MEMORY 27 III.3.2 MONUMENTS 30 III.3.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY 32 IV SPATIALIZING AMERICAN MEMORIES: FRONTIERS, BORDERS, BORDERLANDS 34 IV.1 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY I: THE LAND OF ENCHANTMENT 39 IV.1.1 THE TRI-ETHNIC MYTH 41 IV.2 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY II: HOMELANDS 43 IV.2.1 HISPANO HOMELAND 44 IV.2.2 CHICANO AZTLÁN 46 IV.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY III: BORDER-LANDS 48 V FROM THE SOUTHWEST TO THE BORDERLANDS: LANDSCAPES OF AMERICAN MEMORIES 52 MONOLOGUE: EL PASO AND THE TWELVE TRAVELERS 57 I COMING TO TERMS WITH EL PASO 60 I.1 PLANNING ‘THE CITY OF THE NEW OLD WEST’ 61 I.2 FOUNDATIONAL -

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Online items available Guide to the Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 (805) 893-8563 [email protected] © 2006 Guide to the Centro Cultural de la CEMA 12 1 Raza Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet(153 document boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 13 slide albums, 229 posters, and 975 online items)Online items available Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes).Online items available creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Access Restrictions None. -

Style Sheet for Aztlán: a Journal of Chicano Studies

Style Sheet for Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies Articles submitted to Aztlán are accepted with the understanding that the author will agree to all style changes made by the copyeditor unless the changes drastically alter the author’s meaning. This style sheet is intended for use with articles written in English. Much of it also applies to those written in Spanish, but authors planning to submit Spanish-language texts should check with the editors for special instructions. 1. Reference Books Aztlán bases its style on the Chicago Manual of Style, 15th edition, with some modifications. Spelling follows Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th edition. This sheet provides a guide to a number of style questions that come up frequently in Aztlán. 2. Titles and Subheads 2a. Article titles No endnotes are allowed on titles. Acknowledgments, information about the title or epigraph, or other general information about an article should go in an unnumbered note at the beginning of the endnotes (see section 12). 2b. Subheads Topical subheads should be used to break up the text at logical points. In general, Aztlán does not use more than two levels of subheads. Most articles have only one level. Authors should make the hierarchy of subheads clear by using large, bold, and/or italic type to differentiate levels of subheads. For example, level-1 and level-2 subheads might look like this: Ethnocentrism and Imperialism in the Imperial Valley Social and Spatial Marginalization of Latinos Do not set subheads in all caps. Do not number subheads. No endnotes are allowed on subheads. -

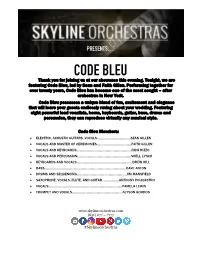

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat.