An Analysis of Baseball Pitch Data: Quantifying the Effect of Speed, Location and Movement on a Batter's Chances of Getting a Hit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARNING FASTBALLS Fastballs to Hit

EARNING FASTBALLS fastballs to hit. You earn fastballs in this way. You earn them by achieving counts where the Pitchers use fastballs a majority of the time. pitcher needs to throw a strike. We’re talking The fastball is the easiest pitch to locate, and about 1‐0, 2‐0, 2‐1, 3‐1 and 3‐2 counts. If the pitchers need to throw strikes. I’d say pitchers in previous hitter walked, it’s almost a given that Little League baseball throw fastballs 80% of the the first pitch you’ll see will be a fastball. And, time, roughly. I would also estimate that of all after a walk, it’s likely the catcher will set up the strikes thrown in Little League, more than dead‐center behind the plate. You could say 90% of them are fastballs. that the patience of the hitter before you It makes sense for young hitters to go to bat earned you a fastball in your wheelhouse. Take looking for a fastball, visualizing a fastball, advantage. timing up for a fastball. You’ll never hit a good fastball if you’re wondering what the pitcher will A HISTORY LESSON throw. Visualize fastball, time up for the fastball, jump on the fastball in the strike zone. Pitchers and hitters have been battling each I work with my players at recognizing the other forever. In the dead ball era, pitchers had curveball or off‐speed pitch. Not only advantages. One or two balls were used in a recognizing it, but laying off it, taking it. -

ASA Official Rules of Softball Umpire Edition

Welcome! Pick here for General Table of Contents Pick here for Playing Rules Table of Contents On this information page you will find: General notes about this rulebook. Other Notes: General notes about this rulebook. SEARCH: This rulebook is presented using Adobe Acrobat®. This allows you the user to search the rulebook for specific text using the Adobe Acrobat®software search tool. Select the binocular icon, type in the word or phrase you are looking for and pick the search button. NAVIGATION: You may navigate the rulebook using the bookmarks shown on the left or from either of the Table of Contents pages. To Navigate using the bookmarks simply select the title of the bookmark and the Acrobat software will take you to that page. To navigate from a Table of Contents page simply select the title or page number you wish to go to. RETURNING TO THE UMPIRE MECHANICS SOFTWARE: The umpire mechanics software is still running when you launch this rulebook. This allows you to switch between the umpire mechanics software and this rulebook. There are several ways to accomplish this on a windows machine. Most commonly the taskbar at the bottom of the screen or using the “Alt” and “Tab” key to cycle through the software programs that are running on your computer. SOFTBALL PLAYING RULES Copyright by the Amateur Softball Association of America REVISED 2005 “Permission to reprint THE OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES has been granted by THE AMATEUR SOFTBALL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA.” Where (Fast Pitch Only) is shown, Modified Pitch rules are followed the same as fast pitch with the exception of the pitching rule. -

Dynamical Chaos in a Simple Model of a Knuckleball

Dynamical Chaos in a Simple Model of a Knuckleball Nicholas J. Nelson, Eric Strauss Department of Physics California State University, Chico 400 W. 1st St. Chico, CA 95929 Abstract The knuckleball is perhaps the most enigmatic pitch in baseball. Relying on the presence of raised seams on the surface of the ball to create asymmetric flow, a knuckleball's trajectory has proven very challenging to predict compared to other baseball pitches, such as fastballs or curveballs. Previous experimental tracking of large numbers of knuckleballs has shown that they can move in essentially any direction relative to what would be expected from a drag-only trajectory. This has led to speculation that knuckleballs exhibit chaotic motion. Here we develop a relatively simple model of a knuckleball that includes quadratic drag and lift from asymmetric flow which is taken from experimental measurements of slowly rotating baseballs. Our models can indeed exhibit dynamical chaos as long In contrast, models that omit torques on the ball in flight do not show chaotic behavior. Uncertainties in the phase space position of the knuckleball are shown to grow by factors as large as 106 over the flight of the ball from the pitcher to home plate. We quantify the impact of our model parameters on the chaos realized in our models, specifically showing that maximum Lyapunov exponent is roughly proportional to the square root of the effective lever arm of the torque, and also roughly proportional to the initial velocity of the pitch. We demonstrate the existence of bifurcations that can produce changes in the location of the ball when it reaches the plate of as much as 1.2 m for specific initial conditions similar to those used by professional knuckleball pitchers. -

Umpire News & Notes / 03 March 2020

Items of interest to baseball umpires, coaches, players, and fans, from the UmpireBible Umpire News & Notes / 03 March 2020 2020 Rule Changes in Official Rules (OBR) Major league baseball has posted rule changes for the 2020 season. The most significant of this year's rule changes is another of those "speed up" rules -- this one mandating that pitchers must face a minimum of three batters before being removed from the game (except for injury or ejection). Make of it what you will. I expect we'll see the occasional pitcher taking a dive. But that's just me. Other changes include shortening the period available for managers to challenge a call (shortened from 30 to 20 seconds), and several administrative items related to roster size, player assignment, and the injured player list. Read the official MLB statement HERE. For more insight, read ESPN coverage HERE. Little League Rulebook Available as Phone App Little League has a phone app that you can download ($1.99) that gives you a comprehensive set of Little League playing rules -- baseball, softball, and Challenger division, all in one app. This one-time download also allows for automatic updates for future seasons. Read about and download the app HERE. New Pickoff Rule in Minor League Class A and Lower More rule changes this year in the minor league "laboratory" for MLB. This one involves a new requirement that left-handed pitcher must step off before making a pickoff attempt at first base. Set to be implemented in Class A and below, the new rule will "eliminate the Andy Pettitte-style pickoff move." This rule was in place in the Atlantic League for the last half of last season and the result was an increase in stolen base attempts, from 1.03 to 1.69 per game. -

BASEBALL UMPIRES MANUAL 37560Textv2.Qxp 1645.Baseballumpbk.Qxd 5/5/16 2:35 PM Page 2

20th Edition 37560textv2.qxp_1645.BaseballUmpBk.qxd 5/5/16 2:35 PM Page 1 BASEBALL UMPIRES MANUAL 37560textv2.qxp_1645.BaseballUmpBk.qxd 5/5/16 2:35 PM Page 2 Published by Alabama High School Athletic Association Additional Copies Available at Alabama High School Athletic Association $10.00 per copy Printed in Montgomery, Alabama by Walker360 May, 2016 37560textv2.qxp_1645.BaseballUmpBk.qxd 5/5/16 2:35 PM Page 3 CONTENTS Code of Ethics ......................................................................... 5 Prerequisites for Good Umpiring........................................... 6 General Reminders.................................................................. 9 Pre-Game Preparations...........................................................10 Pre-Game Checklist.................................................................11 Game Responsibilities ............................................................12 The Plate Umpire .....................................................................12 The Base Umpire .....................................................................26 Observing Bases .....................................................................29 Procedure at End of Game .....................................................29 Communications and Signals ................................................29 Basic Umpiring Positions and Descriptions.........................30 37560textv2.qxp_1645.BaseballUmpBk.qxd 5/5/16 2:35 PM Page 4 Basic Positions........................................................................31 -

Junior Giants Game Rules/Regulations (8-10)

Junior Giants Game Rules/Regulations (Machine Pitch 1) -Score will not be kept at any level. All games are non-competitive and should be treated as such. (Think of it as kids just getting together to play sandlot baseball. Parents/coaches are there to facilitate and try to keep things organized and fun, not to try to beat the other team). -We do not provide specific umpires/officials for the games. A coach/helper will be “pitching” for each team. There may be a parent/helper at 1st and 3rd base to help with base running and to call players safe or out. There will be no arguing decisions at any level. This is non-competitive and free-of-charge. No one should be getting yelled at. Parents are expected to cheer for both teams and all players. Fair/foul and safe/out will be judgment calls. Close or debated decisions will go to the offensive team. Once a quick decision is made it is final and the game will continue. The adult that is “pitching” will have final say if there is a disagreement. We expect issues to be resolved quickly and the game to continue on. - Have a batting order prepared pre-game. Players will bat in one continuous batting order. -Teams will not be allowed to bat more than 9 players in any given inning. Keep a batting order. Because teams may not always bat through their entire lineup each inning, we ask that you change your batting order from game to game, since the leadoff batters will receive more at-bats as the season goes on. -

Pine Tar and the Infield Fly Rule: an Umpire’S Perspective on the Hart-Dworkin Jurisprudential Debate

Pine Tar and the Infield Fly Rule: An Umpire’s Perspective on the Hart-Dworkin Jurisprudential Debate William D. Blake, Ph.D.1 Assistant Professor Department of Political Science Indiana University, Indianapolis (IUPUI) [email protected] Abstract: What is law? Though on its face this question seems simple, it remains an incredibly controversial one to legal theorists. One prominent jurisprudential debate of late occurred between H.L.A. Hart, a positivist, and Ronald Dworkin, an interpretivist. While positivism, at its core, holds the law is a set of authoritative commands, Dworkin rejects this reflexive approach and instructs judges to incorporate and advance communal norms and morals in their decisions. In baseball, umpires utilize both legal theories, depending on the type of rule they are asked to interpret or enforce. I conclude that, like umpires, most citizens are not dogmatic about either legal theory. 1 I wish to thank Justice George Nicholson of the California Court of Appeal for encouraging my participation at this Symposium. I am eternally grateful to former Major Leaguer Jim Abbott for taking the time to respond to my questions. Finally, to the 13 year-old pitcher whom I discuss in this paper: your courage and enthusiasm are inspiring, but, for Pete's sake, please practice coming set. Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2403586 Bill Klem, one of the 2 first umpires inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, once wrongly called a runner out at home plate. A lucky newspaper photographer snapped a shot, which demonstrated Klem’s mistake. The next day, reporters demanded to know how the batter could be out in light of the incontrovertible photographic evidence. -

Ray Herbert Recalls Surprise 20-Win Sox Season in ‘62

Ray Herbert recalls surprise 20-win Sox season in ‘62 By Mark Liptak Posted Wednesday, October 30th, 2013 Winning 20 games is a feat in any era. It’s especially tough in the 21st century with pitchers working on four days’ rest and getting 35 or fewer starts. But it wasn’t a given in the mid-20th cen- tury when a bigger strike zone, no DH and four-man rotations increased the odds of a 20-win season for a capable starter. Some of the best-known Sox pitchers of modern times have not won 20 while working on the South Side – Mark Buehrle, Tommy John, Joel Horlen. Instead, some surprising names reached that pitching bench- mark like Ray Herbert, Esteban Loaiza and Jim Kaat. Herbert connects to the great Sox pitching staff of the 1960s. “Excellent” is the word that best describes a group that lead the American League in ERA Ray Herbert warming up at Comiskey Park during in four of five seasons between 1963 his surprise 20-win season in 1962 . Photo credit: and 1967, that produced 11 All-Stars www.sfmsports.net. from the pitching staff, that had two 20- game winners, three 19- game winners, a “Fireman of the Year”, and four league leaders in ERA during the decade. The names roll off the tongue…Gary Peters, Joe Horlen, Juan Pizarro, Tommy John, Hoyt Wilhelm, Eddie Fisher and Wilbur Wood. But there were also pitchers rather un- heralded, rather forgotten, who also contributed to an organization that averaged 96 wins a year from 1963 to 1965, and 92 wins between 1963 through 1967. -

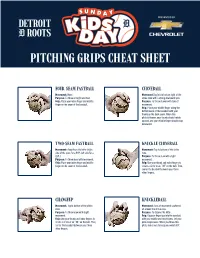

Pitching Grips Cheat Sheet

PITCHING GRIPS CHEAT SHEET FOUR-SEAM FASTBALL CURVEBALL Movement: None Movement:Top left to bottom right of the Purpose: To throw straight and fast. strike zone with a strong downward spin. Grip: Place your index finger and middle Purpose: To throw slower with tons of finger on the seam of the baseball. movement. Grip: Place your middle finger along the bottom seam of the baseball with your thumb on the back seam. When this pitch is thrown, your thumb should rotate upward, and your middle finger should snap downward. TWO-SEAM FASTBALL KNUCKLE CURVEBALL Movement: Away from the hitter (right Movement: Top to bottom of the strike side of the plate for a RHP, left side for a zone. LHP.) Purpose: To throw slow with slight Purpose: To throw hard with movement. movement. Grip: Place your index finger and middle Grip: Use your thumb and index fingers to finger on the seam of the baseball. create a circle or an “OK” on the ball. Then, center the baseball between your three other fingers. CHANGEUP KNUCKLEBALL Movement: Top to bottom of the strike Movement: Tons of movement scattered zone. all around the strike zone. Purpose: To throw slow with slight Purpose: To deceive the hitter. movement. Grip: Dig your fingertips into the baseball Grip: Use your thumb and index fingers to with your middle and ring fingers. Let your create a circle or an “OK” on the ball. Then, pink dangle loose. When you throw this center the baseball between your three pitch, make sure to keep your wrist stiff. other fingers.. -

Baseball Terms

BASEBALL TERMS Help from a fielder in putting an offensive player out. A fielder is credited with an assist when he ASSIST throws a base runner or hitter out at a base. The offensive team’s turn to bat the ball and score. Each player takes a turn at bat until three outs AT BAT are made. Each Batter’s opportunity at the plate is scored as an "at bat" for him. BACKSTOP Fence or wall behind home plate. BALK Penalty for an illegal movement by the pitcher. The rule is designed to prevent pitchers from (Call of Umpire) deliberately deceiving the runners. If called, baserunners advance one base. BALL A pitch outside the strike zone. (Call of Umpire) BASE One of four stations to be reached in turn by the runner. The baseball’s core is made of rubber and cork. Yarn is wound around the rubber and cork centre. BASEBALL Then 2 strips of white cowhide are sewn around the ball. Official baseballs must weigh 5 to 5 1/4 ounces and be 9 to 9 1/4 inches around. A play in which the batter hits the ball in fair territory and reaches at least first base before being BASE HIT thrown out. BASE ON BALLS Walk; Four balls and the hitter advances to first base. A coach who stands by first or third base. The base coaches instruct the batter and base runners BASE COACH with a series of hand signals. The white chalk lines that extend from home plate through first and third base to the outfield and BASE LINE up the foul poles, inside which a batted ball is in fair territory and outside of which it is in foul territory. -

Pony League Playing Rules Grades 5 & 6

PONY LEAGUE PLAYING RULES GRADES 5 & 6 1. Games will be 6 innings; 4 complete will make a complete game in case of rain. Games ending in a tie may be continued if both coaches agree. 2. Each team may play with 10 defensive players; however, only 4 infielders and 4 outfielders. Free substitution will be applied though whole game. 3. Everyone will bat and the batting order will remain constant through the entire game. No player will sit on the bench for more than 2 innings in a game. Late comers to the game will be added onto the end of the line-up. 4. All games will be forfeited 15 minutes after scheduled game time if a team does not have the required number of players present. A team may play with as few as 8 players in a game. 5. Score sheet should be completed before the game starts. Each coach should report to the other bench with their line-ups. Scores should be compared after each inning. 6. No hidden ball tricks. 7. No steel spikes allowed. 8. No balks will be called. 9. All players and equipment must remain on the bench or behind the bench area. 10. Runners may not advance once the pitcher has the ball and is within the pitching area. 11. A 5 run/inning rule will be enforced. 12. Batting helmets will be worn by all batters and runners. Both teams will share their batting helmets. 13. Runner at 3rd cannot advance on an overthrow to 2nd or 1st, but may advance if played upon at 3rd and there is an overthrow or a ball that goes out of play. -

Softball General Rules

SOFTBALL GENERAL RULES The Official Special Olympics Sports Rules shall govern all Special Olympics softball competitions. As an international sports program, Special Olympics has developed these rules based upon Amateur Softball Association of America rules for softball. Amateur Softball Association of America rules shall be employed except when they are in conflict with the Official Special Olympics Sports Rules. For more information, visit www.asasoftball.com. OFFICIAL EVENTS OFFERED ATHLETES CAN COMPETE IN ONLY ONE EVENT! 1. Team Competition 2. Unified Sports Team Competition – Invitational only SECTION A – GENERAL RULES 1. In cases not specifically covered by these rules, Amateur Softball Association Rules are employed except when in conflict with Special Olympics rules. 2. Protests will only be considered for rule infractions (not for umpire judgments). 3. The games rules committee shall make all final judgments. 4. Teams must play a minimum of two (documented) games against other Special Olympics teams prior to registration for district competition. The team roster must remain the same for the two qualifying games, district competition and State competition. Teams that modify their rosters will forfeit all games. Qualifying games must be played against other teams. One game must be played against a team from another Agency. Forfeited games do not count toward the scrimmage requirement. SECTION B – DIVISIONING 1. All teams will play as coed open teams following men's rules. SECTION C - FIELD 1. The field shall conform to ASA rules except when Special Olympics modifications apply. 2. The softball diamond may vary with 60 - 65 foot base lines depending on venue availability for all ages and divisions.