A Tutorial on the Game of Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense of Baseball

In#Defense#of#Baseball# ! ! On!Thursday!afternoon,!May!21,!Madison!Bumgarner!of!the!Giants!and! Clayton!Kershaw!of!the!Dodgers,!arguably!the!two!premiere!left@handers!in!the! National!League,!faCed!off!in!San!FranCisCo.!The!first!run!of!the!game!Came!in!the! Giants’!third,!when!Bumgarner!led!off!with!a!line!drive!home!run!into!the!left@field! bleaChers.!It!was!Bumgarner’s!seventh!Career!home!run,!and!the!first!Kershaw!had! ever!surrendered!to!another!pitCher.!In!the!top!of!the!fourth,!Kershaw!Came!to!bat! with!two!on!and!two!out.!Bumgarner!obliged!him!with!a!fastball!on!a!2@1!count,!and! Kershaw!lifted!a!fairly!deep,!but!harmless,!fly!ball!to!Center!field.!The!Giants!went!on! to!win,!4@0.!Even!though!the!pitChing!matChup!was!the!main!point!of!interest!in!the! game,!the!result!really!turned!on!that!exchange!of!at@bats.!Kershaw!couldn’t!do!to! Bumgarner!what!Bumgarner!had!done!to!him.! ! ! A!week!later,!the!Atlanta!Braves!were!in!San!FranCisCo,!and!the!Giants!sent! rookie!Chris!Heston!to!the!mound,!against!the!Braves’!Shelby!Miller.!Heston!and! Miller!were!even!better!than!Bumgarner!and!Kershaw!had!been,!and!the!game! remained!sCoreless!until!Brandon!Belt!reaChed!Miller!for!a!solo!home!run!in!the! seventh.!Miller!was!due!to!bat!seCond!in!the!eighth!inning,!and!with!the!Braves! behind!with!only!six!outs!remaining,!manager!Fredi!Gonzalez!elected!to!pinch@hit,! even!though!Miller!had!only!thrown!86!pitches.!The!Braves!failed!to!score,!and!with! the!Braves’!starter!out!of!the!game,!the!Giants!steamrolled!the!Braves’!bullpen!for! six!runs!in!the!bottom!of!the!eighth.!They!won!by!that!7@0!score.! -

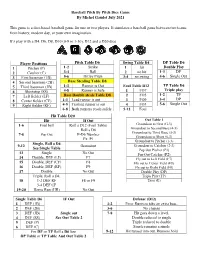

Baseball Pitch by Pitch Dice Game Instruction

Baseball Pitch By Pitch Dice Game By Michel Gaudet July 2021 This game is a dice-based baseball game for one or two players. It simulates a baseball game between two teams from history, modern day, or your own imagination. It’s play with a D4. D6, D8, D10 (0-9 or 1-10), D12 and a D20 dice. Player Positions Pitch Table D6 Swing Table D4 DP Table D6 1 Pitcher (P) 1-2 Strike 1 hit Double Play 2 Catcher (C) 3-4 Ball 2 no hit 1-3 DP 3 First baseman (1B) 5-6 Hit by Pitch 3-4 no swing 4-6 Single Out 4 Second baseman (2B) Base Stealing Table D8 5 Third baseman (3B) 1-3 Runner is Out Foul Table D12 TP Table D6 6 Shortstop (SS) 4-8 Runner is Safe 1 FO7 Triple play 7 Left fielder (LF) Base Double steals Table D8 2 FO5 1-2 TP 8 Center fielder (CF) 1-3 Lead runner is out 3 FO9 3-4 DP 9 Right fielder (RF) 4-5 Trailing runner is out 4 FO3 5-6 Single Out 6-8 Both runners reach safely 5-12 Foul Hit Table D20 Hit If Out Out Table 1 1-6 Foul ball Roll a D12 (Foul Table) Groundout to First (G-3) Roll a D6 Groundout to Second Base (4-3) Groundout to Third Base (5-3) 7-8 Pop Out P-D6 Number Groundout to Short (6-3) Ex. P1 Groundout to Pitcher (1-3) Single, Roll a D6 9-12 Groundout Groundout to Catcher (2-3) See Single Table Pop Out Pitcher (P1) 13 Single No Out Pop Out Catcher (P2) 14 Double, DEF (LF) F7 Fly out to Left Field (F7) 15 Double, DEF (CF) F8 Fly out to Center Field (F8) 16 Double, DEF (RF) F9 Fly out to Right Field (F9) 17 Double No Out Double Play (DP) Triple, Roll a D4, Triple Play (TP) 18 1-2 DEF RF F8 or F9 Error (E) 3-4 DEF CF 19-20 Home Run (HR) No Out Single Table D6 IF Out Defense (D12) 1 DEF (1B) 1-2 Error Runners take an extra base. -

Introduction to Screenwriting 1: the 5 Elements

Introduction to screenwriting 1: The 5 elements by Allen Palmer Session 1 Introduction www.crackingyarns.com.au 1 Can we find a movie we all love? •Avatar? •Lord of the Rings? •Star Wars? •Groundhog Day? •Raiders of the Lost Ark? •When Harry Met Sally? 2 Why do people love movies? •Entertained •Escape •Educated •Provoked •Affirmed •Transported •Inspired •Moved - laugh, cry 3 Why did Aristotle think people loved movies? •Catharsis •Emotional cleansing or purging •What delivers catharsis? •Seeing hero undertake journey that transforms 4 5 “I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive ... ... so that we can actually feel the rapture being alive.” Joseph Campbell “The Power of Myth” 6 What are audiences looking for? • Expand emotional bandwidth • Reminder of higher self • Universal connection • In summary ... • Cracking yarns 7 8 Me 9 You (in 1 min or less) •Name •Day job •Done any courses? Read any books? Written any screenplays? •Have a concept? •Which film would you like to have written? 10 What’s the hardest part of writing a cracking screenplay? •Concept? •Characters? •Story? •Scenes? •Dialogue? 11 Typical script report Excellent Good Fair Poor Concept X Character X Dialogue X Structure X Emotional Engagement X 12 Story without emotional engagement isn’t story. It’s just plot. 13 Plot isn’t the end. It’s just the means. 14 Stories don’t happen in the head. They grab us by the heart. 15 What is structure? •The craft of storytelling •How we engage emotions •How we generate catharsis •How we deliver what audiences crave 16 -

EARNING FASTBALLS Fastballs to Hit

EARNING FASTBALLS fastballs to hit. You earn fastballs in this way. You earn them by achieving counts where the Pitchers use fastballs a majority of the time. pitcher needs to throw a strike. We’re talking The fastball is the easiest pitch to locate, and about 1‐0, 2‐0, 2‐1, 3‐1 and 3‐2 counts. If the pitchers need to throw strikes. I’d say pitchers in previous hitter walked, it’s almost a given that Little League baseball throw fastballs 80% of the the first pitch you’ll see will be a fastball. And, time, roughly. I would also estimate that of all after a walk, it’s likely the catcher will set up the strikes thrown in Little League, more than dead‐center behind the plate. You could say 90% of them are fastballs. that the patience of the hitter before you It makes sense for young hitters to go to bat earned you a fastball in your wheelhouse. Take looking for a fastball, visualizing a fastball, advantage. timing up for a fastball. You’ll never hit a good fastball if you’re wondering what the pitcher will A HISTORY LESSON throw. Visualize fastball, time up for the fastball, jump on the fastball in the strike zone. Pitchers and hitters have been battling each I work with my players at recognizing the other forever. In the dead ball era, pitchers had curveball or off‐speed pitch. Not only advantages. One or two balls were used in a recognizing it, but laying off it, taking it. -

2017 Altoona Curve Final Notes

EASTERN LEAGUE CHAMPIONS DIVISION CHAMPIONS PLAYOFF APPEARANCES PLAYERS TO MLB 2010, 2017 2004, 2010, 2017 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 144 2010, 2015, 2016, 2017 THE 19TH SEASON OF CURVE BASEBALL: Altoona finished the season eight games over .500 and won the Western 2017 E.L. WESTERN STANDINGS Division by two games over the Baysox. The title marked the franchise's third regular-season division championship in Team W-L PCT GB franchise history, winning the South Division in 2004 and the Western Division in 2010. This year, the Curve led the Altoona 74-66 .529 -- West for 96 of 140 games and took over sole possession of the top spot for good on August 22. The Curve won 10 of Bowie 72-68 .514 2.0 their final 16 games, including a regular-season-best five-game winning streak from August 20-24. Altoona clinched the Western Division regular-season title with a walk-off win over Harrisburg on September 4 and a loss by Bowie at Akron 69-71 .493 5.0 Richmond that afternoon. The Curve advanced to the ELCS with a three-game sweep over the Bowie Baysox in the Erie 65-75 .464 9.0 Western Division Series. In the Championship Series, the Curve took the first two games in Trenton before beating Richmond 63-77 .450 11.0 the Thunder, 4-2, at PNG Field on September 14 to lock up their second league title in franchise history. Including the Harrisburg 60-80 .429 14.0 regular season and the playoffs, the Curve won their final eight games, their best winning streak of the year. -

NCAFA Constitution By-Laws, Rules & Regulations Page 2 of 70 Revision January 2020 DEFINITIONS to Be Added

NATIONAL CAPITAL AMATEUR FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION CONSTITUTION BY-LAWS AND RULES AND REGULATIONS January 2020 Changes from the previous version are highlighted in yellow Table of Contents DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................... 3 1 GUIDING PRINCIPLES ................................................................................. 3 2 MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................. 3 3 LEAGUE STRUCTURE ................................................................................. 6 4 EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS........................................................................... 10 5 ADVISORY GROUP .................................................................................... 11 6 MEETINGS .................................................................................................. 11 7 AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION ................................................. 13 8 BY-LAWS AND REGULATIONS ................................................................ 13 9 FINANCES .................................................................................................. 14 10 BURSARIES ............................................................................................ 14 11 SANDY RUCKSTUHL VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR AWARD ............... 15 12 VOLUNTEER SCREENING ..................................................................... 16 13 REMUNERATION ................................................................................... -

How to Maximize Your Baseball Practices

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the author. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ii DEDICATED TO ••• All baseball coaches and players who have an interest in teaching and learning this great game. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to\ thank the following individuals who have made significant contributions to this Playbook. Luis Brande, Bo Carter, Mark Johnson, Straton Karatassos, Pat McMahon, Charles Scoggins and David Yukelson. Along with those who have made a contribution to this Playbook, I can never forget all the coaches and players I have had the pleasure tf;> work with in my coaching career who indirectly have made the biggest contribution in providing me with the incentive tQ put this Playbook together. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS BASEBALL POLICIES AND REGULATIONS ......................................................... 1 FIRST MEETING ............................................................................... 5 PLAYER INFORMATION SHEET .................................................................. 6 CLASS SCHEDULE SHEET ...................................................................... 7 BASEBALL SIGNS ............................................................................. 8 Receiving signs from the coach . 9 Sacrifice bunt. 9 Drag bunt . 10 Squeeze bunt. 11 Fake bunt and slash . 11 Fake bunt slash hit and run . 11 Take........................................................................................ 12 Steal ....................................................................................... -

2019 CVLL JR SR Rules

2021 CVLL Junior & Senior Divisions Playing Rules Please take note that these rules are in addition, not a replacement, to the 2021 Official Little League Rulebook. 1. Home Team Responsibilities: The home team is responsible for the field set up before each game and conditioning the field after each game & practice. This includes putting out/away bases, raking and/or dragging the infield and LOCKING the boxes before you leave. The visiting team is expected to assist the home team. Both teams are responsible for cleaning up dugouts; garbage must be IN the can & not left loosely in the dugout. Failure to do so will result in reduced privileges of the field & equipment; and any equipment lost due to unlocked boxes will be replaced by the home team manager The home team is responsible for recording the score on the league website. 2. Minimum Participation Requirement: A. Each player on a team must play a minimum of 2 innings (6 outs) in every regular season game. a. NOTE: Any player that does not meet the minimum requirements due to the game being shortened because of weather or time limit must play a complete game at the next regular season game. B. CONTINOUS BATTING ORDER: Each team will make up a batting order consisting of all members of the team that are present for the game, regardless of the number of players present for the opposing team. Unlimited defensive substitutions are permitted, however all teams must abide by rule 1A (above). C. No courtesy runners or special pinch runners are permitted with a continuous batting order. -

Davis Double Play”: Making Money in Durable Businesses

How to Use the “Davis Double Play”: Making Money in Durable Businesses (Sign up for Geoff’s free weekly “Gannon on Investing” emails to make sure you never miss an article) The book “The Davis Dynasty” talks about 3 generations of Davis family investors. The one that interests us here is the first generation: “Shelby Davis”. Shelby Davis made a fortune investing – on margin – in insurance stocks. That fortune really came from a “triple play” of returns – each working with the next in a multiplicative rather than an additive way – that led him to compound his money at more than 20% a year for many decades. Davis focused on insurers – businesses unlikely to become obsolete – that were growing and had a low P/E ratio. Not growing too fast. And not stocks with too low a P/E ratio. But, stocks where the growth was high enough to give him some return just from growth and where the P/E ratio expansion could be high enough to give him some return from that too. He also used leverage. A lot of it. I won’t be discussing that part of his returns here. But, obviously, it was a big part of it. If you buy – as he did – about half the shares you own on margin, you’ll amplify your returns (good or bad). Margin loans are a pretty cheap source of debt. However, they’re also a pretty high risk source of debt, because of the constant risk of calls for more collateral. The book – “The Davis Dynasty” – goes into some, but not a lot, of detail on how he managed this. -

St. Louis Amateur Baseball Association Playing Rules

ST. LOUIS AMATEUR BASEBALL ASSOCIATION PLAYING RULES 1.00 ENTRY FEE 1.01 Entry fees, covering association-operating costs, will be paid by each participating team during the year and shall be the responsibility of the head of the organization. Costs should be determined no later than the January regular meeting. 1.02 A deposit of $250.00 will be made at the January meeting by the first team in each organization. Additional teams in an organization will make deposits of $100.00. 1.03 Full payment of all fees shall be due no later than the May regular meeting with the exception of the 14 and 13 & under teams that shall be paid in March. 1.04 Entry fees shall include: affiliation fees, insurance, game balls, trophies, banquet reservations, awards, and any other fee determined by the Executive Board. 1.05 Umpire fees are not part of the entry fee; each team is required to pay one umpire directly on the field prior to the commencement of the game. Umpires are to be paid the exact contracted fee, no more and no less. 2.00 ELIGIBLE PLAYERS, TERRITORIES & RECRUITING 2.01 Eligible Players Each organization can draw players who attend any public or private high school in the immediate St. Louis metropolitan area or adjoining counties (the player’s legal residence is the address recorded at the school the player attends as of March 31 of the current year). While programs do not have exclusive rights to players from “base schools,” the spirit of this rule is that the majority of an organization’s players should be recruited from within a reasonable distance to the home field of that organization. -

Generating Offense Cornerstone!

GENERATING OFFENSE CORNERSTONE! Generating Offense Without Hitting Many times, you will hear coaches and players mistakenly refer to offense strictly as "hitting." They will say things such as "we just didn't hit today," or "we could not hit that pitcher." There is no doubt that on a day when you don't score many runs, those statements are true, however this rationale shows an imperfect understanding of how runs are scored. Coaches and players need to realize that some days, you will not be able to “hit” the pitcher. On days like these, you need to be able to score runs without hitting. This four part series will look at the various ways to generate offense without hitting. Part I: Getting on base There are seven different ways a batter can reach base safely. Two of the seven, are largely out of the control of the hitter (catcher’s interference, drop third strike), and one of them (fielder’s choice) requires that someone already be on base and gives no real offensive advantage. Other than getting a hit, there are three ways to get on base that offense has control over: walk, hit by pitch, or reaching base due to an error. Let’s examine each of those three carefully to determine how your players can give themselves the best chance to get on base without getting a hit. Hit by pitch: Watch a high school or college game and you will hear screams of “wear it!” or “we got ice!” coming from the offensive teams dugout anytime a player jumps out of the way of a pitch. -

Here Comes the Strikeout

LEVEL 2.0 7573 HERE COMES THE STRIKEOUT BY LEONARD KESSLER In the spring the birds sing. The grass is green. Boys and girls run to play BASEBALL. Bobby plays baseball too. He can run the bases fast. He can slide. He can catch the ball. But he cannot hit the ball. He has never hit the ball. “Twenty times at bat and twenty strikeouts,” said Bobby. “I am in a bad slump.” “Next time try my good-luck bat,” said Willie. “Thank you,” said Bobby. “I hope it will help me get a hit.” “Boo, Bobby,” yelled the other team. “Easy out. Easy out. Here comes the strikeout.” “He can’t hit.” “Give him the fast ball.” Bobby stood at home plate and waited. The first pitch was a fast ball. “Strike one.” The next pitch was slow. Bobby swung hard, but he missed. “Strike two.” “Boo!” Strike him out!” “I will hit it this time,” said Bobby. He stepped out of the batter’s box. He tapped the lucky bat on the ground. He stepped back into the batter’s box. He waited for the pitch. It was fast ball right over the plate. Bobby swung. “STRIKE TRHEE! You are OUT!” The game was over. Bobby’s team had lost the game. “I did it again,” said Bobby. “Twenty –one time at bat. Twenty-one strikeouts. Take back your lucky bat, Willie. It was not lucky for me.” It was not a good day for Bobby. He had missed two fly balls. One dropped out of his glove.