Davis Double Play”: Making Money in Durable Businesses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

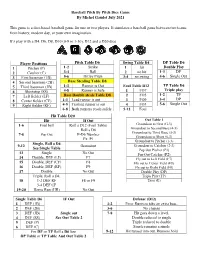

Baseball Pitch by Pitch Dice Game Instruction

Baseball Pitch By Pitch Dice Game By Michel Gaudet July 2021 This game is a dice-based baseball game for one or two players. It simulates a baseball game between two teams from history, modern day, or your own imagination. It’s play with a D4. D6, D8, D10 (0-9 or 1-10), D12 and a D20 dice. Player Positions Pitch Table D6 Swing Table D4 DP Table D6 1 Pitcher (P) 1-2 Strike 1 hit Double Play 2 Catcher (C) 3-4 Ball 2 no hit 1-3 DP 3 First baseman (1B) 5-6 Hit by Pitch 3-4 no swing 4-6 Single Out 4 Second baseman (2B) Base Stealing Table D8 5 Third baseman (3B) 1-3 Runner is Out Foul Table D12 TP Table D6 6 Shortstop (SS) 4-8 Runner is Safe 1 FO7 Triple play 7 Left fielder (LF) Base Double steals Table D8 2 FO5 1-2 TP 8 Center fielder (CF) 1-3 Lead runner is out 3 FO9 3-4 DP 9 Right fielder (RF) 4-5 Trailing runner is out 4 FO3 5-6 Single Out 6-8 Both runners reach safely 5-12 Foul Hit Table D20 Hit If Out Out Table 1 1-6 Foul ball Roll a D12 (Foul Table) Groundout to First (G-3) Roll a D6 Groundout to Second Base (4-3) Groundout to Third Base (5-3) 7-8 Pop Out P-D6 Number Groundout to Short (6-3) Ex. P1 Groundout to Pitcher (1-3) Single, Roll a D6 9-12 Groundout Groundout to Catcher (2-3) See Single Table Pop Out Pitcher (P1) 13 Single No Out Pop Out Catcher (P2) 14 Double, DEF (LF) F7 Fly out to Left Field (F7) 15 Double, DEF (CF) F8 Fly out to Center Field (F8) 16 Double, DEF (RF) F9 Fly out to Right Field (F9) 17 Double No Out Double Play (DP) Triple, Roll a D4, Triple Play (TP) 18 1-2 DEF RF F8 or F9 Error (E) 3-4 DEF CF 19-20 Home Run (HR) No Out Single Table D6 IF Out Defense (D12) 1 DEF (1B) 1-2 Error Runners take an extra base. -

Usssa Fastpitch Rule Book

OFFICIAL FASTPITCH PLAYING RULES and BY-LAWS Fourteenth Edition USSSA, LLC 611 Line Dr Kissimmee, FL 34744 (800) 741-3014 www.usssa.com USSSA National Offices will relocate April 17, 2017: USSSA, LLC 5800 Stadium Parkway Viera, FL 32940 (800) 741-3014 www.usssa.com 14th Edition (2-18 Online revision) 1 USSSA FASTPITCH RULES & BY-LAWS FOURTEENTH EDITION Table of Contents Classifications and Age Requirements ................................................................................4 Changes in Fourteenth Edition Playing Rules ....................................................................5 USSSA Official Fastpitch Playing Rules FOURTEENTH EDITION .............................6 RULE 1. PLAYING FIELD ................................................................................................6 RULE 2. EQUIPMENT ......................................................................................................8 RULE 3. DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................16 RULE 4. THE GAME .......................................................................................................25 RULE 5. PLAYERS AND SUBSTITUTES ....................................................................28 RULE 6. PITCHING RULE .............................................................................................33 RULE 7. BATTING ...........................................................................................................37 RULE 8. BASE RUNNING ..............................................................................................40 -

Iscore Baseball | Training

| Follow us Login Baseball Basketball Football Soccer To view a completed Scorebook (2004 ALCS Game 7), click the image to the right. NOTE: You must have a PDF Viewer to view the sample. Play Description Scorebook Box Picture / Details Typical batter making an out. Strike boxes will be white for strike looking, yellow for foul balls, and red for swinging strikes. Typical batter getting a hit and going on to score Ways for Batter to make an out Scorebook Out Type Additional Comments Scorebook Out Type Additional Comments Box Strikeout Count was full, 3rd out of inning Looking Strikeout Count full, swinging strikeout, 2nd out of inning Swinging Fly Out Fly out to left field, 1st out of inning Ground Out Ground out to shortstop, 1-0 count, 2nd out of inning Unassisted Unassisted ground out to first baseman, ending the inning Ground Out Double Play Batter hit into a 1-6-3 double play (DP1-6-3) Batter hit into a triple play. In this case, a line drive to short stop, he stepped on Triple Play bag at second and threw to first. Line Drive Out Line drive out to shortstop (just shows position number). First out of inning. Infield Fly Rule Infield Fly Rule. Second out of inning. Batter tried for a bunt base hit, but was thrown out by catcher to first base (2- Bunt Out 3). Sacrifice fly to center field. One RBI (blue dot), 2nd out of inning. Three foul Sacrifice Fly balls during at bat - really worked for it. Sacrifice Bunt Sacrifice bunt to advance a runner. -

2020 Baseball

2020 BASEBALL www.nfhs.org NJSIAA BASEBALL EXAM . Opens February 1 . Closes February 28 Format Section 1 Baseball Mechanics 10 questions Section 2 NJSIAA Regulations 10 questions Section 3 NFHS Rule Changes 5 questions Section 4 NFHS Points of Emphasis 5 questions Section 5 Baseball Rules 20 out of 50 questions Passing Score = 80% Chapter Date Time Location ACUA Atlantic County Umpire Association Feb. 10 6:30 PM Mainland Regional HS 69 Oak Avenue Linwood, NJ 69420 Feb. 20 7:30 PM Becton Regional HS BCUA Bergen County Umpire Association 120 Paterson Ave. East Rutherford, NJ 07073 Feb. 6 7 PM Hamilton Library DVUA Delaware Valley Umpire Association 1 Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. Way Hamilton, NJ 08619 Jan. 29 7 PM Bayonne HS / Rich Korpi Ice Rink Facility HCUA Hudson County Umpire Association 28th St and Avenue A Bayonne, NJ 07002 Independent Independent Umpire Association Feb. 19 7 PM Bankbridge Ctr. @ GCIT 555 Salina Road Each Chapter Sewell, NJ Feb. 3 7 PM Bloomfield Library NJSBUA New Jersey State Baseball Umpire Association 160 Broad Street received a Bloomfield, NJ 07003 Feb. 4 7 PM Sterling HS NJBUA-Camden New Jersey Baseball Umpire Association Camden Chapter 501 South Warwick Road Somerdale, NJ 08083 copy of this Feb. 10 7 PM Colonia HS NJSFU New Jersey State Federation of Umpires 180 East Street Colonia, NJ 07067 list at NJSIAA Feb. 5 7 PM Hunterdon Central HS Cafeteria 001 RVUA Raritan Valley Umpire Association 84 Route 31 Flemington, NJ 08822 Interpretation Jan. 30 7 PM Brick Twp. HS Cafeteria 3 Shore Shore Umpire Association 346 Chambers Bridge Road Brick, NJ 98723 Meeting. -

Summer Softball Rules

BOSTON UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION, RECREATION, AND DANCE Scott Nalette - Manager of Intramural Sports 617-353-4364, [email protected] INTRAMURAL SUMMER SOFTBALL ***PLAY AT OWN RISK--Players are reminded that they participate in Intramural Sports at their own risk. Boston University cannot accept liability for the injury of participants in the Intramural Sports Program. Team Captains need to make sure that their players are aware of this before being allowed to participate.*** CAPTAIN'S MEETING - There will be a mandatory team captain's meeting that MUST be attended by a representative, captain or co-captain preferred, from each team. The Captain’s Meeting Schedule can be found at: http://www.bu.edu/fitrec/intramural/. Each team MUST have a representative present. If a team is not represented they waive their right to veto any schedule change proposed at the meeting, and may forfeit their right to future schedule change requests. Bring along this sheet for a reference to discuss the different items. Schedules will also be handed out at this time. CANCELED, POSTPONED, AND RESCHEDULED GAMES – We generally will play games in any weather except lightening. We will usually never make a decision on cancellation before 4:00 PM on day of the game and then will try to hold off as long as possible if there is a chance of playing. If games are cancelled before 5:00pm, teams will be notified via email to the listed captain. Games that are canceled will not always be rescheduled immediately. We may wait until later in the season to see how many games we have to reschedule and what times are available to reschedule them. -

Bunt Defense

Baseball Defense CUTOFF & RELAYS Part 2: Bunt Defense Copyright © 2015 Inside Baseball All rights reserved. Copyright © 2015 Inside Baseball Table of Contents Chapter 20: Bunt Defense - Basic Runner on 1st ......................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 21: Bunt Defense - Play at 3rd with Runners on 1st and 2nd .......................................................................................... 4 Chapter 22: Bunt Defense - “Wheel Play” Shortstop Early Break to 3rd Base with Runners on 1st and 2nd ................................ 5 Chapter 23: Bunt Defense - “Wheel Play” Fake with Pick-Off at 2nd Base with Runners on 1st and 2nd...................................... 6 Chapter 24: Bunt Defense - Fake Pick-Off at 2nd Base with Runners on 1st and 2nd ................................................................ 7 Chapter 25: Bunt Defense – 2nd Baseman Early Break with Runner on 1st ................................................................................ 8 Chapter 26: Bunt Defense - First Baseman Early Break with Runner on 1st ................................................................................ 9 Chapter 27: Bunt Defense - First Baseman Early Break Pick-Off from Catcher with Runner on 1st .......................................... 10 2 Copyright © 2014 Inside Baseball Chapter 20: Bunt Defense - Basic Runner on 1st CF LF RF SS 2B 3B 1B P Positioning: Fly Ball: Ground Ball: Throw: C Pitcher: Move forward to home plate area. React to ball. Catcher: Cover area immediately in front of home plate. Move to cover 3rd base if 3B fields the ball. Make play call for fielders. 1st Baseman: Charge in when pitcher throws ball. Cover 1st base area if ball goes by pitcher. 2nd Baseman: Hold your ground until you are sure the ball has been bunted, then cover 1st base for play.. 3rd Baseman: Charge in when pitcher throws ball. Cover 3rd base area. Shortstop: Hold your ground until you are sure the ball has been bunted, then cover 2nd base for play. -

TABLE of CONTENTS

- The RULES of FASTBALL 45 FASTBALL 45 is innovative and dynamic! An exciting new product with modifications to provide a higher paced and intense version of softball. The concept is designed to enhance the best parts of the game with higher frequency. To achieve this state of play traditional rules have been broken and radicalised to; increase the amount of ball in play, increase double plays, scoring opportunities and the points system itself. FASTBALL 45 Overview: - 45 mins or 4 innings - 3 balls and 3 strikes - 4 outs per inning - Double play clears an inning - Runner(s) starting on base every inning - Double points for successful squeeze plays - Baserunners able to lead off earlier - Offensive power plays - Yellow and red cards. TABLE of CONTENTS Note WBSC rules apply except for the following modifications. 1. THE GAME REGULATION GAME - 4 innings or 45 mins. TIME LIMIT PLAYING RULES © 2019 Softball New Zealand Inc. All rights reserved - Time Limit for all FASTBALL 45 games shall be 45 mins. Where time does not allow for the complete playing of games as per Rule 1.2.1 (SNZ). The following governs the rules surrounding the time keeping of such games. a. One person to monitor time (official scorer) b. If a regulation game is completed prior to time then the game ceases c. If a regulation game is incomplete at time, then the score will revert back to the last completed innings unless the home team (team batting second) is winning. If the last completed innings is a tie, then the winner will be determined by, 1) number of hits 2) number of home runs 3) double plays 4) squeeze plays 5) double steals d. -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

Pitching Grips

Pitching Grips Pitch #1 – Four Seam Fastball The four seam fastball is a pitcher’s bread and butter pitch. It is the pitch you can throw the hardest and with the best control. Place your index and middle fingertips directly on the perpendicular seam of the baseball. The “horseshoe seam” should face into your ring finger of your throwing hand. Next, place your thumb directly beneath the baseball, resting on the smooth leather. Grip this pitch softly, like an egg, in your fingertips. A loose grip minimizes friction between your hand and the baseball. Less friction = more velocity. Pitch #2 – Change-up This pitch is important because: “hitting is timing and pitching is interrupting that timing.” Pitchers must throw a change-up to keep hitters honest, otherwise they will tee off on the fastball. Hold the ball deep in the palm. Circle around the ball with the hand. Use same mechanics as the fastball – except lengthen the stride and drag the back foot. BaseballTutorials.com 1 Pitch #3 – Cut Fastball While the four seam fastball is more or less a straight pitch, the cut fastball has late break toward the glove side of the pitcher. Start with a four-seam fastball grip, and move your top two fingers slightly off center. The arm motion and arm speed for the cutter are just like for a fastball. At the point of release, with the grip slightly off center and pressure from the middle finger, turn your wrist ever so lightly. This off center grip and slight turn of the wrist will result into a pitch with lots of velocity and a late downward break. -

Triple Plays Analysis

A Second Look At The Triple Plays By Chuck Rosciam This analysis updates my original paper published on SABR.org and Retrosheet.org and my Triple Plays sub-website at SABR. The origin of the extensive triple play database1 from which this analysis stems is the SABR Triple Play Project co-chaired by myself and Frank Hamilton with the assistance of dozens of SABR researchers2. Using the original triple play database and updating/validating each play, I used event files and box scores from Retrosheet3 to build a current database containing all of the recorded plays in which three outs were made (1876-2019). In this updated data set 719 triple plays (TP) were identified. [See complete list/table elsewhere on Retrosheet.org under FEATURES and then under NOTEWORTHY EVENTS]. The 719 triple plays covered one-hundred-forty-four seasons. 1890 was the Year of the Triple Play that saw nineteen of them turned. There were none in 1961 and in 1974. On average the number of TP’s is 4.9 per year. The number of TP’s each year were: Total Triple Plays Each Year (all Leagues) Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's <1876 1900 1 1925 7 1950 5 1975 1 2000 5 1876 3 1901 8 1926 9 1951 4 1976 3 2001 2 1877 3 1902 6 1927 9 1952 3 1977 6 2002 6 1878 2 1903 7 1928 2 1953 5 1978 6 2003 2 1879 2 1904 1 1929 11 1954 5 1979 11 2004 3 1880 4 1905 8 1930 7 1955 7 1980 5 2005 1 1881 3 1906 4 1931 8 1956 2 1981 5 2006 5 1882 10 1907 3 1932 3 1957 4 1982 4 2007 4 1883 2 1908 7 1933 2 1958 4 1983 5 2008 2 1884 10 1909 4 1934 5 1959 2 -

NFHS NEW DESIGNATED HITTER RULE 2020 Player May Be Listed As Both the Fielder and the DH

NFHS NEW DESIGNATED HITTER RULE 2020 Player may be listed as both the fielder and the DH. Player may be substituted for defensively and still be the DH. Once the DH is substituted for on offense, the role of DH is extinguished for the game and only one player may occupy that spot in the batting order. If the pitcher or catcher are listed as P/DH or C/DH they are NOT allowed courtesy runners. The player listed in the starting lineup as fielder/DH may come out of the game in either role and re-enter once. Sanders is listed as the P/DH, hitting in the third position in the batting order. In the fifth inning, McNeely enters the game as pitcher with Sanders reaching his pitch count limit. Sanders continues as DH for McNeely. Ruling: Legal 3. Sanders P /DH McNeely (5) P In the 6th inning, substitute Jackson enters to pitch replacing McNeely. Sanders remains the DH for Sanders. Ruling:Legal 3. Sanders P /DH McNeely (5) P Jackson (6) P In the 7th inning, Sanders returns to defense as the catcher and is still listed as the DH. Ruling: Legal Sanders was a starter and is eligible to re-enter the game once. 3. Sanders P /DH/C McNeely (5) P Jackson (6) P With Dolan listed in the starting lineup as the 2B/DH and batting 4th in the order, the coach wants to bring in Tatelman to hit for Dolan. Ruling: If substitute Tatelman comes in to hit (or run) for Dolan, the role of the DH is terminated for the game. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 206 2018 International Conference on Advances in Social Sciences and Sustainable Development (ASSSD 2018) Second baseman defense techniques in a double play with runner on first Haonan Yuan Tianjin University Renai College, Tianjin 30163, china [email protected] Keywords: First base manned; Second baseman; Double play; Defensive technique Abstract: In the baseball game, the second is a key base for runner. The second baseman plays a key role in the game. In addition to his ability possess other fielders, he must be sensitive, light, fast, and steady. The most important thing is to keep head clear and clearly understand the situation on the field. This article finds out the relevant information of second baseman's double play technique by searching a large number of documents. complete each step of the technical movement in the most reasonable and fastest way, and use some basic theoretical links to practice to effectively highlight the value of the second baseman completing the double play in the game. 1. Introduction In the baseball game, the second is a key base for runner. If you can enter the second base, you have a great hope of scoring. Therefore, the second is generally called the score base. The second baseman plays a key role in the game. In addition to his ability possess other fielders, he must be sensitive, light, fast, and steady. The most important thing is to keep head clear and clearly understand the situation on the field. In a baseball game, an infielder received a ground ball and passed it to the second baseman to block the runnerwho runs from the first base to the second base, then the second baseman or the shortstop caught the ball,touched the base, threw the ball to the first base to stop runner.