Effects of Aging on Circadian Patterns of Gene Expression in the Human Prefrontal Cortex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNA·RNA Triple Helix Formation Can Function As a Cis-Acting Regulatory

DNA·RNA triple helix formation can function as a cis-acting regulatory mechanism at the human β-globin locus Zhuo Zhoua, Keith E. Gilesa,b,c, and Gary Felsenfelda,1 aLaboratory of Molecular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; bUniversity of Alabama at Birmingham Stem Cell Institute, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294; and cDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294 Contributed by Gary Felsenfeld, February 4, 2019 (sent for review January 4, 2019; reviewed by James Douglas Engel and Sergei M. Mirkin) We have identified regulatory mechanisms in which an RNA tran- of the criteria necessary to establish the presence of a triplex script forms a DNA duplex·RNA triple helix with a gene or one of its structure, we first describe and characterize triplex formation at regulatory elements, suggesting potential auto-regulatory mecha- the FAU gene in human erythroid K562 cells. FAU encodes a nisms in vivo. We describe an interaction at the human β-globin protein that is a fusion containing fubi, a ubiquitin-like protein, locus, in which an RNA segment embedded in the second intron of and ribosomal protein S30. Although fubi function is unknown, the β-globin gene forms a DNA·RNA triplex with the HS2 sequence posttranslational processing produces S30, a component of the within the β-globin locus control region, a major regulator of glo- 40S ribosome. We used this system to refine methods necessary bin expression. We show in human K562 cells that the triplex is to detect triplex formation and to distinguish it from R-loop stable in vivo. -

Ldb1 Is Essential for Development of Nkx2.1 Lineage Derived Gabaergic and Cholinergic Neurons in the Telencephalon

Developmental Biology 385 (2014) 94–106 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/developmentalbiology Ldb1 is essential for development of Nkx2.1 lineage derived GABAergic and cholinergic neurons in the telencephalon Yangu Zhao a,n,1, Pierre Flandin b,2, Daniel Vogt b, Alexander Blood a, Edit Hermesz a,3, Heiner Westphal a, John L. R. Rubenstein b,nn a Program on Genomics of Differentiation, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA b Department of Psychiatry and the Nina Ireland Laboratory of Developmental Neurobiology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA article info abstract Article history: The progenitor zones of the embryonic mouse ventral telencephalon give rise to GABAergic and cholinergic Received 1 June 2013 neurons. We have shown previously that two LIM-homeodomain (LIM-HD) transcription factors, Lhx6 and Received in revised form Lhx8, that are downstream of Nkx2.1, are critical for the development of telencephalic GABAergic and 8 October 2013 cholinergic neurons. Here we investigate the role of Ldb1, a nuclear protein that binds directly to all LIM-HD Accepted 9 October 2013 factors, in the development of these ventral telencephalon derived neurons. We show that Ldb1 is expressed Available online 21 October 2013 in the Nkx2.1 cell lineage during embryonic development and in mature neurons. Conditional deletion of Ldb1 Keywords: causes defects in the expression of a series of genes in the ventral telencephalon and severe impairment in the Differentiation tangential migration of cortical interneurons from the ventral telencephalon. -

Open Dogan Phdthesis Final.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Eberly College of Science ELUCIDATING BIOLOGICAL FUNCTION OF GENOMIC DNA WITH ROBUST SIGNALS OF BIOCHEMICAL ACTIVITY: INTEGRATIVE GENOME-WIDE STUDIES OF ENHANCERS A Dissertation in Biochemistry, Microbiology and Molecular Biology by Nergiz Dogan © 2014 Nergiz Dogan Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 ii The dissertation of Nergiz Dogan was reviewed and approved* by the following: Ross C. Hardison T. Ming Chu Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee David S. Gilmour Professor of Molecular and Cell Biology Anton Nekrutenko Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Robert F. Paulson Professor of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Philip Reno Assistant Professor of Antropology Scott B. Selleck Professor and Head of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Genome-wide measurements of epigenetic features such as histone modifications, occupancy by transcription factors and coactivators provide the opportunity to understand more globally how genes are regulated. While much effort is being put into integrating the marks from various combinations of features, the contribution of each feature to accuracy of enhancer prediction is not known. We began with predictions of 4,915 candidate erythroid enhancers based on genomic occupancy by TAL1, a key hematopoietic transcription factor that is strongly associated with gene induction in erythroid cells. Seventy of these DNA segments occupied by TAL1 (TAL1 OSs) were tested by transient transfections of cultured hematopoietic cells, and 56% of these were active as enhancers. Sixty-six TAL1 OSs were evaluated in transgenic mouse embryos, and 65% of these were active enhancers in various tissues. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Download Download

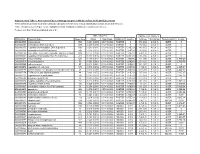

Supplementary Figure S1. Results of flow cytometry analysis, performed to estimate CD34 positivity, after immunomagnetic separation in two different experiments. As monoclonal antibody for labeling the sample, the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- conjugated mouse anti-human CD34 MoAb (Mylteni) was used. Briefly, cell samples were incubated in the presence of the indicated MoAbs, at the proper dilution, in PBS containing 5% FCS and 1% Fc receptor (FcR) blocking reagent (Miltenyi) for 30 min at 4 C. Cells were then washed twice, resuspended with PBS and analyzed by a Coulter Epics XL (Coulter Electronics Inc., Hialeah, FL, USA) flow cytometer. only use Non-commercial 1 Supplementary Table S1. Complete list of the datasets used in this study and their sources. GEO Total samples Geo selected GEO accession of used Platform Reference series in series samples samples GSM142565 GSM142566 GSM142567 GSM142568 GSE6146 HG-U133A 14 8 - GSM142569 GSM142571 GSM142572 GSM142574 GSM51391 GSM51392 GSE2666 HG-U133A 36 4 1 GSM51393 GSM51394 only GSM321583 GSE12803 HG-U133A 20 3 GSM321584 2 GSM321585 use Promyelocytes_1 Promyelocytes_2 Promyelocytes_3 Promyelocytes_4 HG-U133A 8 8 3 GSE64282 Promyelocytes_5 Promyelocytes_6 Promyelocytes_7 Promyelocytes_8 Non-commercial 2 Supplementary Table S2. Chromosomal regions up-regulated in CD34+ samples as identified by the LAP procedure with the two-class statistics coded in the PREDA R package and an FDR threshold of 0.5. Functional enrichment analysis has been performed using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Table S6. Names and Functions of 44 Target Genes and 4 Housekeeping Genes Assessed for Gene Expression Measurements

Table S6. Names and functions of 44 target genes and 4 housekeeping genes assessed for gene expression measurements. Gene Gene name Function Category Reference CD45 CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) Regulation of T-cell and B-cell antigen receptor signaling Adaptive NCBI, UniProt HIVEP2 Human immunodeficiency virus typeI enhancer2 Transcription factor, V(D)J recombination, MHC enhancer binding Adaptive (Diepeveen et al. 2013) HIVEP3 Human immunodeficiency virus typeI enhancer3 Transcription factor, V(D)J recombination, MHC enhancer binding Adaptive (Diepeveen et al. 2013) IgM-lc Immunoglobulin light chain Recognition of antigen or pathogen Adaptive NCBI, UniProt Integ-Bt Integrin-beta 1 Cell signaling and adhesion of immunoglobulin Adaptive NCBI, UniProt Lymph75 Lymphocyte antigen 75 Directs captured antigens to lymphocytes Adaptive (Birrer et al. 2012) Lympcyt Lymphocyte cytosolic protein 2 Positive role in promoting T-cell development and activation Adaptive NCBI, UniProt TAP Tap-binding protein (Tapasin) Transport of antigenic peptides, peptide loading on MHC I Adaptive NCBI, UniProt AIF Allograft inflammation factor Inflammatory responses, allograft rejection, activation of macrophages Innate (Roth et al. 2012) Calrcul Calreticulin Chaperone, promotes phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells Innate NCBI, UniProt Cf Coagulation factor II Blood clotting and inflammation response Innate (Birrer et al. 2012) IL8 Interleukin 8 Neutrophil chemotactic factor, phagocytosis, inflammatory activity Innate NCBI, UniProt Intf Interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 Negative regulation of viral entry into host cell, antiviral response Innate NCBI, UniProt Kin Kinesin Intracellular transport Innate (Roth et al. 2012) LectptI Lectin protein type I Pathogen recognition receptors (C-type lectin type I) Innate NCBI, UniProt LectpII Lectin protein type II Pathogen recognition receptors (C-type lectin type II) Innate NCBI, UniProt Nramp Natural resistance-assoc macrophage protein Macrophage activation Innate (Roth et al. -

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

Mygene.Info R Client

MyGene.info R Client Adam Mark, Ryan Thompson, Chunlei Wu May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Overview ..............................2 2 Gene Annotation Service ...................2 2.1 getGene .............................2 2.2 getGenes ............................2 3 Gene Query Service ......................3 3.1 query ..............................3 3.2 queryMany ...........................4 4 makeTxDbFromMyGene....................5 5 Tutorial, ID mapping .......................6 5.1 Mapping gene symbols to Entrez gene ids ........6 5.2 Mapping gene symbols to Ensembl gene ids .......7 5.3 When an input has no matching gene ...........8 5.4 When input ids are not just symbols ............8 5.5 When an input id has multiple matching genes ......9 5.6 Can I convert a very large list of ids?............ 11 6 References ............................. 11 MyGene.info R Client 1 Overview MyGene.Info provides simple-to-use REST web services to query/retrieve gene annotation data. It’s designed with simplicity and performance emphasized. mygene is an easy-to-use R wrapper to access MyGene.Info services. 2 Gene Annotation Service 2.1 getGene • Use getGene, the wrapper for GET query of "/gene/<geneid>" service, to return the gene object for the given geneid. > gene <- getGene("1017", fields="all") > length(gene) [1] 1 > gene["name"] [[1]] NULL > gene["taxid"] [[1]] NULL > gene["uniprot"] [[1]] NULL > gene["refseq"] [[1]] NULL 2.2 getGenes • Use getGenes, the wrapper for POST query of "/gene" service, to return the list of gene objects for the given character vector of geneids. > getGenes(c("1017","1018","ENSG00000148795")) DataFrame with 3 rows and 7 columns 2 MyGene.info R Client query _id X_version entrezgene name <character> <character> <integer> <character> <character> 1 1017 1017 4 1017 cyclin dependent kin. -

Supplementary Material

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Page 1 / 45 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Appendix A1: Neuropsychological protocol. Appendix A2: Description of the four cases at the transitional stage. Table A1: Clinical status and center proportion in each batch. Table A2: Complete output from EdgeR. Table A3: List of the putative target genes. Table A4: Complete output from DIANA-miRPath v.3. Table A5: Comparison of studies investigating miRNAs from brain samples. Figure A1: Stratified nested cross-validation. Figure A2: Expression heatmap of miRNA signature. Figure A3: Bootstrapped ROC AUC scores. Figure A4: ROC AUC scores with 100 different fold splits. Figure A5: Presymptomatic subjects probability scores. Figure A6: Heatmap of the level of enrichment in KEGG pathways. Kmetzsch V, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2021; 92:485–493. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324647 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Appendix A1. Neuropsychological protocol The PREV-DEMALS cognitive evaluation included standardized neuropsychological tests to investigate all cognitive domains, and in particular frontal lobe functions. The scores were provided previously (Bertrand et al., 2018). Briefly, global cognitive efficiency was evaluated by means of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (MDRS). Frontal executive functions were assessed with Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), forward and backward digit spans, Trail Making Test part A and B (TMT-A and TMT-B), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), and Symbol-Digit Modalities test. -

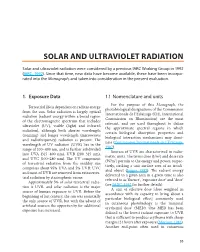

Solar and Ultraviolet Radiation

SOLAR AND ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION Solar and ultraviolet radiation were considered by a previous IARC Working Group in 1992 (IARC, 1992). Since that time, new data have become available, these have been incorpo- rated into the Monograph, and taken into consideration in the present evaluation. 1. Exposure Data 1.1 Nomenclature and units For the purpose of this Monograph, the Terrestrial life is dependent on radiant energy photobiological designations of the Commission from the sun. Solar radiation is largely optical Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE, International radiation [radiant energy within a broad region Commission on Illumination) are the most of the electromagnetic spectrum that includes relevant, and are used throughout to define ultraviolet (UV), visible (light) and infrared the approximate spectral regions in which radiation], although both shorter wavelength certain biological absorption properties and (ionizing) and longer wavelength (microwaves biological interaction mechanisms may domi- and radiofrequency) radiation is present. The nate (Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage, wavelength of UV radiation (UVR) lies in the 1987). range of 100–400 nm, and is further subdivided Sources of UVR are characterized in radio- into UVA (315–400 nm), UVB (280–315 nm), metric units. The terms dose (J/m2) and dose rate and UVC (100–280 nm). The UV component (W/m 2) pertain to the energy and power, respec- of terrestrial radiation from the midday sun tively, striking a unit surface area of an irradi- comprises about 95% UVA and 5% UVB; UVC ated object (Jagger, 1985). The radiant energy and most of UVB are removed from extraterres- delivered to a given area in a given time is also trial radiation by stratospheric ozone.