Blacksburg Master Chorale Mendelssohn’S Elijah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

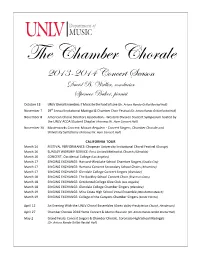

Chamber Chorale Tour Program 2014

The Chamber Chorale 2013-2014 Concert Season David B. Weiller, conductor Spencer Baker, pianist October 18 UNLV Choral Ensembles: If Music Be the Food of Love (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) November 7 29th Annual Invitational Madrigal & Chamber Choir Festival (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) November 8 American Choral Directors Association - Western Division Student Symposium hosted by the UNLV ACDA Student Chapter (Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall) November 30 Masterworks Concert: Mozart Requiem - Concert Singers, Chamber Chorale and University Symphony (Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall) CALIFORNIA TOUR March 14 FESTIVAL PERFORMANCE: Chapman University Invitational Choral Festival (Orange) March 16 SUNDAY WORSHIP SERVICE: First United Methodist Church (Glendale) March 16 CONCERT: Occidental College (Los Angeles) March 17 SINGING EXCHANGE: Harvard-Westlake School Chamber Singers (Studio City) March 17 SINGING EXCHANGE: Ramona Convent Secondary School Choirs (Alhambra) March 17 SINGING EXCHANGE: Glendale College Concert Singers (Glendale) March 18 SINGING EXCHANGE: The Buckley School Concert Choir (Sherman Oaks) March 18 SINGING EXCHANGE: Occidental College Glee Club (Los Angeles) March 18 SINGING EXCHANGE: Glendale College Chamber Singers (Glendale) March 19 SINGING EXCHANGE: Mira Costa High School Vocal Ensemble (Manhattan Beach) March 19 SINGING EXCHANGE: College of the Canyons Chamber Singers (Santa Clarita) April 12 An Evening With the UNLV Choral Ensembles (Green Valley Presbyterian Church, Henderson) April 27 Chamber Chorale 2014 Home Concert & Alumni Reunion (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) May 2 Grand Finale: Concert Singers & Chamber Chorale, Coronado High School Madrigals (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) - Program - The program will be selected from the following repertoire. THE GREATEST OF THESE IS LOVE Warum, Op. -

MEDIA RELEASE Diane Wittry Outstanding Alumnus Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Michael Dowlan [email protected] (213) 740-3233 Images available upon request DIANE WITTRY RECEIVES USC THORNTON SCHOOL OF MUSIC’S OUTSTANDING ALUMNUS AWARD Presented annually at USC Thornton’s Honors Convocation, the Outstanding Alumnus Award is conferred upon a Thornton graduate whose artistic or scholarly accomplishments reflect the ideals of the school and further the art of music. LOS ANGELES (April 23, 2013) – On Thursday, May 16, the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music will present the Outstanding Alumnus Award to acclaimed conductor Diane Wittry as part of the School’s Honors Convocation. She will also address the USC Thornton graduating class the following day during the official Commencement Ceremony. Wittry, who graduated with honors from USC Thornton in 1983 and earned a Master’s from the school two years later, is an esteemed music director, guest conductor, composer, and author. Past winners of USC Thornton’s Outstanding Alumnus Award have included 2007 National Medal of Arts recipient Morten Lauridsen; Grant Gershon, music director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale and resident conductor of the Los Angeles Opera; the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet (LAGQ); conductor Michael Tilson Thomas; and opera star Marilyn Horne, among many others. “We are thrilled to celebrate Diane Wittry with the Outstanding Alumnus Award,” said Robert Cutietta, Dean of the USC Thornton School of Music. “Her work as a conductor, music director, composer, and author is a perfect example of how her entrepreneurial spirit has led to a successful career, serving as a model for others to follow.” Wittry currently serves as the music director of the Allentown Symphony Orchestra, where she has championed an exciting, innovative programming style for concerts of all types. -

Lectures and Community Engagement 2017–18 About the Metropolitan Opera Guild

Lectures and Community Engagement 2017 –18 About the Metropolitan Opera Guild The Metropolitan Opera Guild is the world’s premier arts educa- tion organization dedicated to enriching people’s lives through the magic and artistry of opera. Thanks to the support of individuals, government agencies, foundations, and corporate sponsors, the Guild brings opera to life both on and off the stage through its educational programs. For students, the Guild fosters personal expression, collaboration, literacy skills, and self-confidence with customized education programs integrated into the curricula of their schools. For adults, the Guild enhances the opera-going experience through intensive workshops, pre-performance talks, and community outreach programs. In addition to educational activities, the Guild publishes Opera News, the world’s leading opera magazine. With Opera News, the Guild reaches a global audience with the most insightful and up-to-date writing on opera available anywhere, helping to maintain opera as a thriving, contemporary art form. For more information about the Metropolitan Opera Guild and its programs, visit metguild.org. Additional information and archives of Opera News can be found online at operanews.com. How to Use This Booklet This brochure presents the 2017–18 season of Lectures and Community Programs grouped into thematic sections—programs that emphasize specific Met performances and productions; courses on opera and its history and culture; and editorial insights and interviews presented by our colleagues at Opera News. Courses of study are arranged chronologically, and learners of all levels are welcome. To place an order, please call the Guild’s ticketing line at 212.769.7028 (Mon–Fri 10AM–4PM). -

Review Downloaded from by University of California, Irvine User on 18 March 2021 Performance

Review Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/34/4/355/5469296 by University of California, Irvine user on 18 March 2021 Performance Review Colloquy: The Exterminating Angel Met Live in HD, November 18, 2017 Music: Thomas Ade`s Libretto: Tom Cairns, in collaboration with the composer, based on the screenplay by Luis Bunuel~ and Luis Alcoriza Conductor: Thomas Ade`s Director: Tom Cairns Set and Costume Design: Hildegard Bechtler Lighting Design: Jon Clark Projection Design: Tal Yarden Choreography: Amir Hosseinpour Video Director: Gary Halvorson Edmundo de Nobile: Joseph Kaiser Lucıa de Nobile: Amanda Echalaz Leticia Maynar: Audrey Luna Leonora Palma: Alice Coote Silvia de Avila: Sally Matthews Francisco de Avila: Iestyn Davies Blanca Delgado: Christine Rice Alberto Roc: Rod Gilfry Beatriz: Sophie Bevan Eduardo: David Portillo Raul Yebenes: Frederic Antoun Colonel Alvaro Gomez: David Adam Moore Sen~or Russell: Kevin Burdette Dr. Carlos Conde: Sir John Tomlinson The Opera Quarterly Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 355–372; doi: 10.1093/oq/kbz001 Advance Access publication April 16, 2019 # The Author(s) 2019. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: [email protected] 356 | morris et al Editorial Introduction The pages of The Opera Quarterly have featured individual and panel reviews of op- era in performance both in its traditional theatrical domain and on video, including Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/34/4/355/5469296 by University of California, Irvine user on 18 March 2021 reports from individual critics and from panels assembled to review a single produc- tion or series of productions on DVD. -

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

Department Historyrevised Copy

The Music Department of Wayne State University A History: 1994-2019 By Mary A. Wischusen, PhD To Wayne State University on its Sesquicentennial Year, To the Music Department on its Centennial Year, and To all WSU music faculty and students, past, present, and future. ii Contents Preface and Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………...........v Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………............................ix Dennis Tini, Chair: 1993-2005 …………………………………………………………………………….1 Faculty .…………………………………………………………………………..............................2 Staff ………………………………………………………………………………………………...7 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………................................7 Societies and Organizations ……………………………………………..........................................8 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives …………………………………………………9 Outreach and Recruitment Programs …………………………………………….……………….15 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...18 Awards and Honors ……………………………………………………………………………….21 Other Noteworthy Concerts and Events …………………………………………………………..24 John Vander Weg, Chair: 2005-2013 ………………………………………………................................37 Faculty………………………………………………………………..............................................37 Staff …………………………………………………………………………………………….....39 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………..............................40 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives ……………………………………………..…41 Outreach and Recruitment Programs ……………………………………………………………..45 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...47 Awards -

Rockwell New Kids in the Neighborhood

Mark Singleton, Artistic Director Rockwell New Kids in the Neighborhood joined by The Vernon Chorale and Conard High School’s Solo Choir and featuring the CCSU University Singers, directed by Dr. Pamela Perry Voce Chamber Artists, Dylan Armstrong, oboe, Tom Cooke, clarinet and Dan Campolieta, piano October 20, 2012 7:30 p.m. Immanuel Congregational Church 10 Woodland Street, Hartford, Connecticut 06105 PROGRAM I Tonight Eternity Alone From Dusk at Sea, by Thomas S. Jones, Jr. René Clausen (1953 - ) Tonight eternity alone is near, The sunset and the dark’ning blue, Tonight eternity alone is near, There is no place for fear, Only the wonder of its truth. All That Hath Life & Breath Praise Ye the Lord! adapted from Psalms 96 and 22 René Clausen Sarah Armstrong, soprano All that hath life and breath praise ye the Lord, Shout to the Lord, Alleluia! Praise the Lord with joyful song, Sing to the Lord with thanksgiving, Alleluia, praise Him! Praise the Lord with joyful song, Alleluia Sing to the Lord a new-made song, Praise His name, Alleluia. Unto Thee, O Lord, have I made supplication, and cried unto the rock of my salvation; But Thou hast heard my voice, and renewed my weary spirit. All that hath life and breath praise ye the Lord, Shout to the Lord, Alleluia! Praise Him, laud, Him, Alleluia! II Entreat Me Not to Leave You Adapted from, Ruth 1:16-17 Dan Forrest (1978 - ) Entreat me not to leave you, nor turn back from following after you. For where you go, I will go; And where you live, I will live; Your people shall be my people, And your God, my God. -

Los Angeles Master Chorale Celebrates the 20Th Anniversary Of

PRESS RELEASE Media Contact: Jennifer Scott [email protected] | 213-972-3142 LOS ANGELES MASTER CHORALE CELEBRATES 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF LUX AETERNA BY MORTEN LAURIDSEN & SHOWCASES LOS ANGELES COMPOSERS WITH CONCERTS & GALA JUNE 17-22 Clockwise, l-r: Composers Eric Whitacre, Morten Lauridsen, Shawn Kirchner, Moira Smiley, Billy Childs, & Esa-Pekka Salonen. Concerts include world premieres by Billy Childs and Moira Smiley, a West Coast premiere by Eric Whitacre, and works by Shawn Kirchner and Esa-Pekka Salonen 1 3 5 N O R T H G R A N D AV E N U E , LO S A N G E L E S , C A L I F O R N I A 9 0 0 1 2 - -- 3 0 1 3 2 1 3 - 9 7 2 - 3 1 2 2 | L A M A ST E R C H O R A L E . O R G LUX AETERNA 20TH ANNIVERSARY, PAGE 2 First performances of Lux Aeterna with full orchestra in Walt Disney Concert Hall, conducted by Grant Gershon Gala to honor Morten Lauridsen on Sunday, June 18 Saturday, June 17 – 2 PM Matinee Concert Sunday, June 18 – 6 PM Concert, Gala, & Lux Onstage Party Thursday, June 22 – 8 PM “Choir Night” Concert & Group Sing CONCERT TICKETS START AT $29 LAMASTERCHORALE.ORG | 213-972-7282 (Los Angeles, CA) May 31, 2017 – The Los Angeles Master Chorale brings works by six Los Angeles composers together on a concert program celebrating the 20th anniversary of Morten Lauridsen’s choral masterwork Lux Aeterna June 17-22 in Walt Disney Concert Hall. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Alumni Newsletter

Alumni University of New Hampshire Newsletter Department of Music Fall 2013 Greetings from the Chair During the past year the Department of You may recall from my message conclusion of the 2014-15 academic Music remained a vibrant center for the last year that we are in the process year, completing a remarkable career composition, performance, teaching, of reaccreditation from the National of 43 years as a member of the UNH study, and research of music. On Association of Schools of Music (NASM). Department of Music, and 52 years campus, we presented some 14 faculty This past spring, we received the NASM as a college professor. David Seiler’s recitals, 28 large concert ensemble Visitor’s Report, which expressed accomplishments over the years concerts, 8 jazz ensemble concerts, 6 concerns regarding NASM standards have been unparalleled, not only as Traditional Jazz concerts, 17 daytime to which we were required to respond. an educator, but in service to the student potpourri recitals, and 49 junior, We were able to secure many items as Department and University. He was senior, and graduate recitals. The a result: more access to the Johnson responsible for the establishment of Department also hosted 6 guest master Theater for rehearsals and concerts, an both the Dorothy Prescott Endowment classes, and 5 guest recitals. upgrading of audio/visual equipment in and the Terry – Seiler – Verrette our classrooms, and an improvement Endowment. In an extraordinary We continue with 4 weeks of summer of building security for our majors. We demonstration of support from the instruction offered to young musicians now have an up-to-date electronic music University, the Provost’s office has through SYMS (high school age), Jr. -

ANIOŁ ZAGŁADY THOMAS ADÈS Dyrektor Naczelny Tomasz Bęben Dyrektor Artystyczny Paweł Przytocki Chórmistrz, Szef Chóru Dawid Ber

ANIOŁ ZAGŁADY THOMAS ADÈS dyrektor naczelny Tomasz Bęben dyrektor artystyczny Paweł Przytocki chórmistrz, szef chóru Dawid Ber dyrektor generalny Peter Gelb honorowy dyrektor muzyczny James Levine dyrektor muzyczny Yannick Nézet-Séguin główny dyrygent Fabio Luisi 2. ANIOŁ ZAGŁADY (THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL) OPERA W TRZECH AKTACH LIBRETTO: TOM CAIRNS WE WSPÓŁPRACY Z KOMPOZYTOREM NA PODSTAWIE FILMU LUISA BUÑUELA POD TYM SAMYM TYTUŁEM OSOBY Lucía, markiza de Nobile, gospodyni sopran Leticia Maynar, śpiewaczka operowa sopran koloraturowy Leonora Palma mezzosopran Silvia, hrabina Ávila, młoda owdowiała matka sopran Blanca Delgado, pianistka, żona Roca mezzosopran Beatriz, narzeczona Eduarda sopran Edmundo, markiz de Nobile, gospodarz tenor hrabia Raúl Yebenes, odkrywca tenor pułkownik Álvaro Gómez baryton Francisco de Ávila, brat Silvii kontratenor Eduardo, narzeczony Beatriz tenor Señor Russell bas-baryton Alberto Roc, dyrygent bas-baryton Doktor Carlos Conde bas Julio, kamerdyner baryton Lucas, lokaj tenor Enrique, kelner tenor Pablo, kucharz baryton Meni, pokojówka sopran Camila, pokojówka mezzosopran Padre Sansón baryton Yoli, synek Silvii dyszkant chłopięcy Chór (SABT) grający służących, policjantów, wojskowych, tłum Prapremiera podczas Salzburger Festspiele – 28 lipca 2016 roku Premiera inscenizacji w The Metropolitan Opera w Nowym Jorku – 26 października 2017 roku Współpraca i koprodukcja Metropolitan Opera, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Royal Danish Theatre i Salzburg Festival Transmisja z The Metropolitan Opera w Nowym Jorku – 18 -

“Lux: a Concert on Themes of Light and Hope” Saturday, March 19, 2016 8:00Pm Gerald R

CHAMBER CHOIR UNIVERSITY CHOIR JONATHAN TALBERG, CONDUCTOR GUK-HUI HAN, PIANO “LUX: A CONCERT ON THEMES OF LIGHT AND HOPE” SATURDAY, MARCH 19, 2016 8:00PM GERALD R. DANIEL RECITAL HALL PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. LUX: A CONCERT ON THEMES OF LIGHT AND HOPE (This evening’s 65-minute concert will be presented without an intermission) PROGRAM CSULB UNIVERSITY CHOIR Jonathan Talberg—conductor I Was Glad .......................................................................................................................................................... C. Hubert Parry (1848-1918) Bar Xizam ............................................................................................................................................................... Abbie Betinis (b. 1980) Sammy Sohn, Emilio Peña, Amanda Mitton—soloists; Vasken Ohanian—assistant conductor Agnus Dei .................................................................................................................................................................Gabriel Fauré from Requiem (1845-1924) The Peace of Wild Things ...................................................................................................................................... Jake Runestad (b. 1986) Hymn to the Creator of Light ....................................................................................................................................John Rutter (b. 1945) BOB COLE CONSERVATORY CHAMBER CHOIR Jonathan Talberg—conductor Дух Твой Благий (Let Thy Good Spirit) .....................................................................................................Pavel