James Whitbourn the Seven Heavens and Other Choral Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

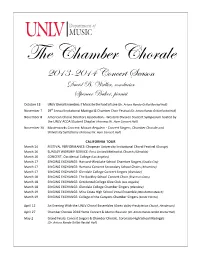

Chamber Chorale Tour Program 2014

The Chamber Chorale 2013-2014 Concert Season David B. Weiller, conductor Spencer Baker, pianist October 18 UNLV Choral Ensembles: If Music Be the Food of Love (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) November 7 29th Annual Invitational Madrigal & Chamber Choir Festival (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) November 8 American Choral Directors Association - Western Division Student Symposium hosted by the UNLV ACDA Student Chapter (Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall) November 30 Masterworks Concert: Mozart Requiem - Concert Singers, Chamber Chorale and University Symphony (Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall) CALIFORNIA TOUR March 14 FESTIVAL PERFORMANCE: Chapman University Invitational Choral Festival (Orange) March 16 SUNDAY WORSHIP SERVICE: First United Methodist Church (Glendale) March 16 CONCERT: Occidental College (Los Angeles) March 17 SINGING EXCHANGE: Harvard-Westlake School Chamber Singers (Studio City) March 17 SINGING EXCHANGE: Ramona Convent Secondary School Choirs (Alhambra) March 17 SINGING EXCHANGE: Glendale College Concert Singers (Glendale) March 18 SINGING EXCHANGE: The Buckley School Concert Choir (Sherman Oaks) March 18 SINGING EXCHANGE: Occidental College Glee Club (Los Angeles) March 18 SINGING EXCHANGE: Glendale College Chamber Singers (Glendale) March 19 SINGING EXCHANGE: Mira Costa High School Vocal Ensemble (Manhattan Beach) March 19 SINGING EXCHANGE: College of the Canyons Chamber Singers (Santa Clarita) April 12 An Evening With the UNLV Choral Ensembles (Green Valley Presbyterian Church, Henderson) April 27 Chamber Chorale 2014 Home Concert & Alumni Reunion (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) May 2 Grand Finale: Concert Singers & Chamber Chorale, Coronado High School Madrigals (Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall) - Program - The program will be selected from the following repertoire. THE GREATEST OF THESE IS LOVE Warum, Op. -

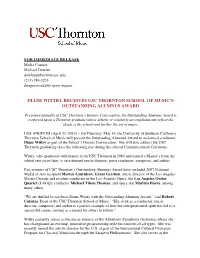

MEDIA RELEASE Diane Wittry Outstanding Alumnus Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Michael Dowlan [email protected] (213) 740-3233 Images available upon request DIANE WITTRY RECEIVES USC THORNTON SCHOOL OF MUSIC’S OUTSTANDING ALUMNUS AWARD Presented annually at USC Thornton’s Honors Convocation, the Outstanding Alumnus Award is conferred upon a Thornton graduate whose artistic or scholarly accomplishments reflect the ideals of the school and further the art of music. LOS ANGELES (April 23, 2013) – On Thursday, May 16, the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music will present the Outstanding Alumnus Award to acclaimed conductor Diane Wittry as part of the School’s Honors Convocation. She will also address the USC Thornton graduating class the following day during the official Commencement Ceremony. Wittry, who graduated with honors from USC Thornton in 1983 and earned a Master’s from the school two years later, is an esteemed music director, guest conductor, composer, and author. Past winners of USC Thornton’s Outstanding Alumnus Award have included 2007 National Medal of Arts recipient Morten Lauridsen; Grant Gershon, music director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale and resident conductor of the Los Angeles Opera; the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet (LAGQ); conductor Michael Tilson Thomas; and opera star Marilyn Horne, among many others. “We are thrilled to celebrate Diane Wittry with the Outstanding Alumnus Award,” said Robert Cutietta, Dean of the USC Thornton School of Music. “Her work as a conductor, music director, composer, and author is a perfect example of how her entrepreneurial spirit has led to a successful career, serving as a model for others to follow.” Wittry currently serves as the music director of the Allentown Symphony Orchestra, where she has championed an exciting, innovative programming style for concerts of all types. -

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

The Role of Fitrah As an Element in the Personality of a Da’I in Achieving the Identity of a True Da’I

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 4 [Special Issue - February 2012] THE ROLE OF FITRAH AS AN ELEMENT IN THE PERSONALITY OF A DA’I IN ACHIEVING THE IDENTITY OF A TRUE DA’I Zaizul Ab. Rahman Jabatan Usuluddin dan Falsafah Islamic Studies Faculty Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Malaysia Abstract In the era of fast-paced development, a dā„ī is constantly faced with a variety of challenges as a result of globalization, among which are attacks on mentality headed and sponsored by other religious groups. A strong element of true fitrah (which translates as „disposition‟) is a critical requirement in dealing with these challenges by supplying oneself with knowledge, faith and good deeds. With these elements, a dā„ī can face the era of globalization that is so rife with tribulations. A dā„ī that has no true identity is an easy mark for exploitation by those with interest in doing so. Introduction Fitrah is a highly important factor in shaping the identity of a dā„ī who is capable of carrying out a successful mission in his da‟wah movements. A dā„ī who is not in possession of an element of fitrah that has been sown with the seeds of an untainted personality cannot face the trials he will encounter from the target audience of his da‟wah. This is especially so if a comparison is made to the missionaries of other religions such as Christianity, whose missions move systematically and with detailed planning. Fitrah in Developing the Personality of a Dā‘ī In Islam, “tendency” may bear similarity to the term “fitrah”. -

Heaven in the Early History of Western Religions

Alison Joanne GREIG University of Wales Trinity Saint David MA in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology Module Name: Dissertation Module Code: AHAH7001 Alison Joanne Greig Student No. 27001842 31 December 2012 Heaven in the early history of Western religions Chapter 1 Approaches to concepts of heaven This dissertation examines concepts of heaven in the early history of Western religions and the extent to which themes found in other traditions are found in Christianity. Russell, in A History of Heaven, investigates the origins of the concept of heaven, which he dates at about 200 B.C.E. and observes that heaven, a concept that has shaped much of Christian thought and attitudes, has been strangely neglected by modern historians.1 Christianity has played a central role in Western civilization and instructs its believers to direct their life in this world with a view to achieving eternal life in the next, as observed by Liebeschuetz. 2 It is of the greatest historical importance that a very large number of people could for many centuries be persuaded to see life in an imperfect visible world as merely a stage in their progress to a world that was perfect but invisible; yet, it has been neglected as a subject for study. Russell notes that Heaven: A History3 by McDannell and Lang mainly offers sociological insights.4 Russell holds that the most important aspects of the concept of heaven are the beatific vision and the mystical union.5 Heaven, he says, is the state of being in 1 Jeffrey Burton Russell, A History of Heaven – The Singing Silence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997) xiii, xiv. -

Department Historyrevised Copy

The Music Department of Wayne State University A History: 1994-2019 By Mary A. Wischusen, PhD To Wayne State University on its Sesquicentennial Year, To the Music Department on its Centennial Year, and To all WSU music faculty and students, past, present, and future. ii Contents Preface and Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………...........v Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………............................ix Dennis Tini, Chair: 1993-2005 …………………………………………………………………………….1 Faculty .…………………………………………………………………………..............................2 Staff ………………………………………………………………………………………………...7 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………................................7 Societies and Organizations ……………………………………………..........................................8 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives …………………………………………………9 Outreach and Recruitment Programs …………………………………………….……………….15 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...18 Awards and Honors ……………………………………………………………………………….21 Other Noteworthy Concerts and Events …………………………………………………………..24 John Vander Weg, Chair: 2005-2013 ………………………………………………................................37 Faculty………………………………………………………………..............................................37 Staff …………………………………………………………………………………………….....39 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………..............................40 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives ……………………………………………..…41 Outreach and Recruitment Programs ……………………………………………………………..45 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...47 Awards -

Rockwell New Kids in the Neighborhood

Mark Singleton, Artistic Director Rockwell New Kids in the Neighborhood joined by The Vernon Chorale and Conard High School’s Solo Choir and featuring the CCSU University Singers, directed by Dr. Pamela Perry Voce Chamber Artists, Dylan Armstrong, oboe, Tom Cooke, clarinet and Dan Campolieta, piano October 20, 2012 7:30 p.m. Immanuel Congregational Church 10 Woodland Street, Hartford, Connecticut 06105 PROGRAM I Tonight Eternity Alone From Dusk at Sea, by Thomas S. Jones, Jr. René Clausen (1953 - ) Tonight eternity alone is near, The sunset and the dark’ning blue, Tonight eternity alone is near, There is no place for fear, Only the wonder of its truth. All That Hath Life & Breath Praise Ye the Lord! adapted from Psalms 96 and 22 René Clausen Sarah Armstrong, soprano All that hath life and breath praise ye the Lord, Shout to the Lord, Alleluia! Praise the Lord with joyful song, Sing to the Lord with thanksgiving, Alleluia, praise Him! Praise the Lord with joyful song, Alleluia Sing to the Lord a new-made song, Praise His name, Alleluia. Unto Thee, O Lord, have I made supplication, and cried unto the rock of my salvation; But Thou hast heard my voice, and renewed my weary spirit. All that hath life and breath praise ye the Lord, Shout to the Lord, Alleluia! Praise Him, laud, Him, Alleluia! II Entreat Me Not to Leave You Adapted from, Ruth 1:16-17 Dan Forrest (1978 - ) Entreat me not to leave you, nor turn back from following after you. For where you go, I will go; And where you live, I will live; Your people shall be my people, And your God, my God. -

Los Angeles Master Chorale Celebrates the 20Th Anniversary Of

PRESS RELEASE Media Contact: Jennifer Scott [email protected] | 213-972-3142 LOS ANGELES MASTER CHORALE CELEBRATES 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF LUX AETERNA BY MORTEN LAURIDSEN & SHOWCASES LOS ANGELES COMPOSERS WITH CONCERTS & GALA JUNE 17-22 Clockwise, l-r: Composers Eric Whitacre, Morten Lauridsen, Shawn Kirchner, Moira Smiley, Billy Childs, & Esa-Pekka Salonen. Concerts include world premieres by Billy Childs and Moira Smiley, a West Coast premiere by Eric Whitacre, and works by Shawn Kirchner and Esa-Pekka Salonen 1 3 5 N O R T H G R A N D AV E N U E , LO S A N G E L E S , C A L I F O R N I A 9 0 0 1 2 - -- 3 0 1 3 2 1 3 - 9 7 2 - 3 1 2 2 | L A M A ST E R C H O R A L E . O R G LUX AETERNA 20TH ANNIVERSARY, PAGE 2 First performances of Lux Aeterna with full orchestra in Walt Disney Concert Hall, conducted by Grant Gershon Gala to honor Morten Lauridsen on Sunday, June 18 Saturday, June 17 – 2 PM Matinee Concert Sunday, June 18 – 6 PM Concert, Gala, & Lux Onstage Party Thursday, June 22 – 8 PM “Choir Night” Concert & Group Sing CONCERT TICKETS START AT $29 LAMASTERCHORALE.ORG | 213-972-7282 (Los Angeles, CA) May 31, 2017 – The Los Angeles Master Chorale brings works by six Los Angeles composers together on a concert program celebrating the 20th anniversary of Morten Lauridsen’s choral masterwork Lux Aeterna June 17-22 in Walt Disney Concert Hall. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Revelation, Session 4 Seven Trumpets Revelation 8:6-11:19 It Is

Revelation, Session 4 Seven Trumpets Revelation 8:6-11:19 It is perhaps most helpful not to think of this central section of Revelation as a kind of timeline, with the drama of the seals followed by the drama of the trumpets followed by the drama of the bowls. Rather what we have here is a kind of triptych, with three panels set up beside each other. Or we can think of it as a kind of split screen motion picture with events juxtaposed against each other simultaneously. In each case what Revelation affirms is the power of judgment and the hope of redemption. In each case the power of the judgment is presented in such dramatic, almost overwhelming images that it is hard to grasp the hope, but in each case there is a fundamental affirmation of salvation that is there if we can pay enough attention, or rally enough faith. The depiction of the trumpet will in itself will resonate with John’s readers or hearers. There is the trumpet that calls people to worship at the temple. There is the trumpet that sounded before the fall of Jericho. There is the trumpet that is regularly part of the scenario for the last days in early Christian expectation: “For the Lord himself, with a cry of command, with the archangel’s call and with the sound of God’s trumpet, will descend from heaven, and the dead in Christ will rise first.” (1Thess. 4:16) “Listen, I will tell you a mystery, we will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. -

Alumni Newsletter

Alumni University of New Hampshire Newsletter Department of Music Fall 2013 Greetings from the Chair During the past year the Department of You may recall from my message conclusion of the 2014-15 academic Music remained a vibrant center for the last year that we are in the process year, completing a remarkable career composition, performance, teaching, of reaccreditation from the National of 43 years as a member of the UNH study, and research of music. On Association of Schools of Music (NASM). Department of Music, and 52 years campus, we presented some 14 faculty This past spring, we received the NASM as a college professor. David Seiler’s recitals, 28 large concert ensemble Visitor’s Report, which expressed accomplishments over the years concerts, 8 jazz ensemble concerts, 6 concerns regarding NASM standards have been unparalleled, not only as Traditional Jazz concerts, 17 daytime to which we were required to respond. an educator, but in service to the student potpourri recitals, and 49 junior, We were able to secure many items as Department and University. He was senior, and graduate recitals. The a result: more access to the Johnson responsible for the establishment of Department also hosted 6 guest master Theater for rehearsals and concerts, an both the Dorothy Prescott Endowment classes, and 5 guest recitals. upgrading of audio/visual equipment in and the Terry – Seiler – Verrette our classrooms, and an improvement Endowment. In an extraordinary We continue with 4 weeks of summer of building security for our majors. We demonstration of support from the instruction offered to young musicians now have an up-to-date electronic music University, the Provost’s office has through SYMS (high school age), Jr. -

“Lux: a Concert on Themes of Light and Hope” Saturday, March 19, 2016 8:00Pm Gerald R

CHAMBER CHOIR UNIVERSITY CHOIR JONATHAN TALBERG, CONDUCTOR GUK-HUI HAN, PIANO “LUX: A CONCERT ON THEMES OF LIGHT AND HOPE” SATURDAY, MARCH 19, 2016 8:00PM GERALD R. DANIEL RECITAL HALL PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. LUX: A CONCERT ON THEMES OF LIGHT AND HOPE (This evening’s 65-minute concert will be presented without an intermission) PROGRAM CSULB UNIVERSITY CHOIR Jonathan Talberg—conductor I Was Glad .......................................................................................................................................................... C. Hubert Parry (1848-1918) Bar Xizam ............................................................................................................................................................... Abbie Betinis (b. 1980) Sammy Sohn, Emilio Peña, Amanda Mitton—soloists; Vasken Ohanian—assistant conductor Agnus Dei .................................................................................................................................................................Gabriel Fauré from Requiem (1845-1924) The Peace of Wild Things ...................................................................................................................................... Jake Runestad (b. 1986) Hymn to the Creator of Light ....................................................................................................................................John Rutter (b. 1945) BOB COLE CONSERVATORY CHAMBER CHOIR Jonathan Talberg—conductor Дух Твой Благий (Let Thy Good Spirit) .....................................................................................................Pavel