Higginbotham School Historic District 8730 Chippewa Street Draft Preliminary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-2009 Bill Witt

2008-2009 Title 1 Schools Required to Offer Supplemental Educational Services (SES) Title I schools that have not made Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for three or more consecutive years are required by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) to offer free tutoring to eligible students. District Name School Name Phase Academy for Business and Technology Academy for Business and Technology High 4 School Academy of Oak Park Academy of Oak Park - High School 5 Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy 2 School School Benton Harbor Area Schools Hull Middle School 6 Buena Vista School District Buena Vista High School 4 Ricker Middle School 5 Casa Richard Academy Casa Richard Academy 4 Casman Alternative Academy Casman Alternative Academy 3 Center for Literacy and Creativity Center for Literacy and Creativity 2 Cesar Chavez Academy Cesar Chavez High School 2 Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences High 2 School Detroit City School District Barbara Jordan Elementary 5 Barbour Magnet Middle School 8 Beckham, William Academy 6 Boykin Continuing Ed. Center 5 Boynton Elementary-Middle School 2 Central High School 5 Chadsey High School 5 Cleveland Middle School 8 Cody High School 5 Columbus Middle School 6 Communication and Media Arts HS 3 Cooley High School 5 Cooley North Wing 2 Courtis Elementary School 5 Crockett High School 4 Crosman Alternative High School 5 Denby High School 5 Detroit High School for Technology 2 Douglass Academy 4 Drew Middle School 8 Page 1 of 3 District -

Youth Urban Agenda Program AGENDA-BUILDING GUIDE

WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Urban Agenda/Civic Literacy Project A Civic Education Program for Urban and Suburban Youth Implemented through Middle School, High School and Post-Secondary and Adult Education and Community Organizations Youth Urban Agenda Program AGENDA-BUILDING GUIDE YOU HAVE A VOICE . LET IT BE HEARD! Cover Layout: Tina Samaddar Photos: Ella Singer Edited by: Ella Singer & Tina Samaddar Check Out Our Web-Site!! www.urbanagenda.wayne.edu WSU-based non-profit organization promoting civic education in the schools and in the community WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Urban Agenda/Civic Literacy Project 2002 FAB Wayne State University Detroit, MI 48201 313 577 2235 313 993 3435(Fax) YOUTH URBAN AGENDA PROGRAM: An Introductory Packet Table of Contents: What is Civic Literacy? 3 About the Project . 4 The Curriculum 5 Michigan Content Standards and Draft Benchmarks as applied to Youth Urban Agenda Program 15 An Event: 17 October 27, 1998 Youth Urban Agenda Convention at Cobo Hall WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY 2 Urban Agenda/Civic Literacy Project What is Civic Literacy? Civic Literacy is the knowledge of how to actively participate and initiate change in your community and the greater society. It is the foundation by which a democratic society functions: Citizen Power as a check and as a means to create avenues for peaceful change. Why an Agenda? · Civic participation not only encompasses voting in elections but also a consciousness about the issues that are most important to an individual and his or her community. Creating an agenda is an avenue to gather support and raise awareness for both community members and elected officials about what’s happening in the community. -

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH STREET ACADEMY NC 21ST CENTURY ALTERNATIVE MO 21ST CENTURY COMMUNITY SCHOOLHOUSE OR 21ST CENTURY CYBER CS PA 270 HOPKINS ALC MN 270 HOPKINS ALT. PRG - OFF CAMPUS MN 270 HOPKINS HS ALC MN 271 KENNEDY ALC MN 271 MINDQUEST OLL MN 271 SHAPE ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA HS ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA SR. ALC MN 276-MINNETONKA RSR-ALC MN 279 IS ALC MN 279 SR HI ALC MN 281 HIGHVIEW ALC MN 281 ROBBINSDALE TASC ALC MN 281 WINNETKA LEARNING CTR. ALC MN 3-6 PROG (BNTFL HIGH) UT 3-6 PROG (CLRFLD HIGH) UT 3-B DENTENTION CENTER ID 622 ALT MID./HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 FARMINGTON HS. MN 917 HASTINGS HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 LAKEVILLE SR. HIGH MN 917 SIBLEY HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 SIMLEY HIGH SCHOOL SP. ED. MN A & M CONS H S TX A B SHEPARD HIGH SCH (CAMPUS) IL A C E ALTER TX A C FLORA HIGH SC A C JONES HIGH SCHOOL TX A C REYNOLDS HIGH NC A CROSBY KENNETT SR HIGH NH A E P TX A G WEST BLACK HILLS HIGH SCHOOL WA A I M TX A I M S CTR H S TX A J MOORE ACAD TX A L BROWN HIGH NC A L P H A CAMPUS TX A L P H A CAMPUS TX A MACEO SMITH H S TX A P FATHEREE VOC TECH SCHOOL MS A. C. E. AZ A. C. E. S. CT A. CRAWFORD MOSLEY HIGH SCHOOL FL A. D. HARRIS HIGH SCHOOL FL A. -

Evaluation of the 1996-97 Ninth Grade Restructuring Program. Area A. INSTITUTION Research and Evaluation Specialists, Inc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 246 UD 032 187 AUTHOR Syropoulos, Mike TITLE Evaluation of the 1996-97 Ninth Grade Restructuring Program. Area A. INSTITUTION Research and Evaluation Specialists, Inc. SPONS AGENCY Detroit Public Schools, MI. Office of Research, Evaluation, and Testing. PUB DATE 1997-10-00 NOTE 265p. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110)-- Reports - Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Attitude Change; *Dropout Prevention; *Grade 9; *High School Students; High Schools; Principals; Program Evaluation; Public Schools; *School Restructuring; Tables (Data); Teacher Attitudes; *Teachers; Teaching Methods; *Urban Schools; Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS *Detroit Public Schools MI ABSTRACT The Ninth Grade Restructuring Program of the Detroit (Michigan) public schools was designed to restructure the ninth grade in ways that improve academic performance, develop positive attitudes toward learning, improve the school environment, reduce the dropout rate, and increase the graduation rate of students. Features of the program were instructional and direct noninstructional services, such as social work services, counseling and psychological services, tutoring by student assistants with teacher supervision, and parent participation in instructional and noninstructional activities. This report presents findings from the second year evaluation in Area A of the Detroit schools. Six principals completed a survey, and 83% believed that the program boosted student achievement. Teachers (n=58) generally thought (77%) that the program raised student achievement. Seven ninth grade administrators who responded also generally thought that the program raised achievement. Teachers and both groups of administrators identified areas in which improvements could be made and recommended its continuation. Recommendations included: the fostering of a school-within-a-school environment; continuing block scheduling; continuing to create clusters of students; and continuing to sensitize teachers to the special needs of ninth graders. -

Download the 2014/2015 Annual Report

ContentsTable of of Donors Early Childhood Education Our Priorities Donors 2 6 6 & Other GrantsSTEM Awarded 16 11 Finances If Not Me, Who? 3 11 7 Finances Board of DirectorsOther Foundation12 Staff Beyond the Classroom 17 Development Committee STEM Early Childhood Education The DPS Foundation has been creating and 4 12 Alumni AdvisoryBoard & Board Staff enhancing educational opportunities for Detroit Public 8 13 Schools students since 2009. This report contains activity for the 2014/15 school year. Fine & Performing Arts Academics 5 1410 Fine & Performing Arts MISSION Create and enhance educational opportunities for Detroit Public Schools students. VISION Every DPS student will receive the support needed to achieve his/her highest academic potential. GOALS Provide the resources to support the delivery of a holistic education to every student. Engage alumni, the DPS community, and other stakeholders in assisting and inspiring DPS students. Become the organization of choice for the As you read this report, a snapshot of the DPS Foundation in contribution of DR. GLENDA D. PRICE 2014-15 will emerge. You will learn about our priorities, the philanthropic dollars in support of DPS. PRESIDENT grants we have been able to award, and the sources of our DPS FOUNDATION funding. You will see the power that comes from the professional passion and commitment of teachers, and our partners, along with those who support our mission. This report If not me, who? That is the question that the many donors listed features just a few examples of the impact of our grant making. in this report answered for themselves. They knew that they had a responsibility to join others to ensure that our children We all want the expanded opportunities for educational had an opportunity to receive a comprehensive education in the experiences to continue. -

Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) / Human Rights Department Records

Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) / Human Rights Department Records This finding aid was created using ArchivesSpace on July 24, 2019 English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) / Human Rights Department Records This finding aid was created using ArchivesSpace on July 24, 2019 English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records UR000267 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials .......................................................................................................................................... -

Doors Swing Wide at Normal College Lola Lohse 182 Students Take Classes New Dean the Normal College Doors Had to Mrs

Winter, 1971 Vol. LY, No. 1 1010 W. 64th Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46260 Doors Swing Wide At Normal College Lola Lohse 182 Students Take Classes New Dean The Normal College doors had to Mrs. (Henry) Lola L. Lohse was swing exce ptionally wide to appointed as dean of the Normal College, accommodate the 37 .9% registration A.G.U., by action of the Indiana increase. On August 23, 182 students, 62 juniors, and University Board of Trust~es at their freshmen , 58 sophomores, 42 September 18, 1971 meeting. This action 20 seniors enrolled for first semester bears out fully the promise made by classes. Daughters of two alumni were Indiana University at the merger of among the new students. Elizabeth of Stephen Normal College and Indiana University in Rychnowski 1 daughter September, 1941. At that time l.U. Rychnowski of Buffalo, N.Y., and promised that the Normal College would Kathleen Wilson, step daughter of always retain its identity. We know the Richard Udvardi of South Bend, Indiana, alumni will be gratified that this promise both registered for Normal classes. has been fulfilled. NORMAL COLLEGE PICNIC..• No one scratches this event. Throughout the past year physical Mrs. Lohse has served as director of property improvements have been made. the Normal College since 1963. Her Strange as it may seem, everything on appointment as dean followed closely campus is practically on ground level. The upon the initiation of the four year From Our Mailbox highest anyone has to climb is two steps, program leading to the B.S. degree in Marion Dadeker Schoenly-Last April 5, 1970. -

2008-2009 BINDER All Title 1 HP Schools

2008-2009 All Title 1 HP Schools Title I High Priority Schools receive Title I, Part A funds and have not made Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for two or more consecutive years and are therefore in a phase of school improvement. District Name School Name Phase Title 1 Status Academy for Business and Academy for Business and 4Yes Technology Technology High School Academy of Inkster Academy of Inkster 1 Yes Academy of Oak Park Academy of Oak Park - High School 5 Yes Academy of Waterford Academy of Waterford 1 Yes Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. 2Yes Prep. Academy School Academy School Arts Academy in the Woods Arts Academy in the Woods 1 Yes Battle Creek Area Learning Battle Creek Area Learning Center 1 Yes Center Benton Harbor Area Schools Benton Harbor High School 5 Yes Fair Plain Renaissance MIddle 1Yes School Hull Middle School 6 Yes Blanche Kelso Bruce Blanche Kelso Bruce Academy- 4Yes Academy Connor Buena Vista School District Buena Vista High School 4 Yes Ricker Middle School 5 Yes Business Entrepreneurship, Business Entrepreneurship, 1Yes Science, Tech. Academy Science, Tech. Academy Casa Richard Academy Casa Richard Academy 4 Yes Casman Alternative Academy Casman Alternative Academy 3 Yes Center for Literacy and Center for Literacy and Creativity 2 Yes Creativity Cesar Chavez Academy Cesar Chavez High School 2 Yes Charlotte Forten Academy Charlotte Forten Academy 5 Yes Conner Creek Academy Conner Creek Academy - High 1 Yes Covenant House Life Skills Covenant House Life Skills Center 1Yes Center Central Central Page 1 of 6 District Name School Name Phase Title 1 Status Covenant House Life Skills Covenant House Life Skills Center 1Yes Center East East Covenant House Life Skills Covenant House Life Skills Center 1Yes Center West West Detroit Academy of Arts and Detroit Academy of Arts and 1Yes Sciences Sciences Detroit Academy of Arts and 2Yes Sciences High School Detroit City School District Boykin Continuing Ed. -

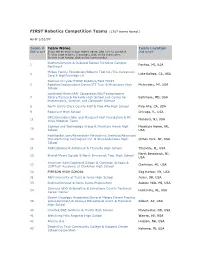

FIRST Robotics Competition Teams (1307 Teams Found.)

FIRST Robotics Competition Teams (1307 teams found.) As of 1/31/07 Team # Team Name Team Location Click to sort If you see an error in your team's name, click here to correct it. Click to sort To view team website, if available, click on the team name. To view team history, click on the team number. DaimlerChrysler & Oakland School Technical Campus 1 Pontiac, MI, USA Northeast Milken Family Foundation/Roberts Tool Co./The Carcannon 4 Lake Balboa, CA, USA Corp & HighTechHigh-LA Daimler-Chrysler/FIRST Robotics/Ford FIRST 5 Robotics/Independent Donor/ITT Tech & Melvindale High Melvindale, MI, USA School Lockheed Martin/AAI Corporation/BD/Towsontowne 7 Rotary/Tessco & Parkville High School and Center for Baltimore, MD, USA Mathematics, Science, and Computer Science 8 North Santa Clara County ROP & Palo Alto High School Palo Alto, CA, USA 9 Roosevelt High School Chicago, IL, USA DPC/Givaudan/John and Margaret Post Foundation & Mt. 11 Flanders, NJ, USA Olive Robotics Team Science and Technology Group & Mountain Home High Mountain Home, AR, 16 School USA HostRocket.com/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute/Advanced 20 Manufacturing Techniques Inc. & Shenendehowa High Clifton Park, NY, USA School 21 ASRC/Boeing & Astronaut & Titusville High School Titusville, FL, USA North Brunswick, NJ, 25 Bristol-Myers Squibb & North Brunswick Twp. High School USA American Axle/Copeland Gibson & Clarkston Schools & 27 Clarkston, MI, USA OSMTech Academy at Clarkston High School 28 PIERSON HIGH SCHOOL Sag Harbor, NY, USA 31 AEP/University of Tulsa & Jenks High School Jenks, OK, USA 33 DaimlerChrysler & Notre Dame Preparatory Auburn Hills, MI, USA Siemens VDO Automotive & Limestone County Technical 34 Huntsville, AL, USA Career Center Desert Oncology Associates/General Motors Desert Proving 39 Grounds/Intel/US Airways Educational Grant & Highland Gilbert, AZ, USA High School 40 intelitek/BAE Systems & Trinity High School Manchester, NH, USA 41 Watchung Hills Regional High School Warren, NJ, USA 42 Alvirne H.S. -

Aaa School House Aaa School House

December 5th, 2008 AAA SCHOOL HOUSE ACCOUNTABILITY + ADDED VALUE = ACHIEVEMENT Detroit Public Schools Employee Newsletter DPS BOARD CARSTENS ANNOUNCES OPPORTU- THREE DPS HIGH ‘ANGELS’ LEND A NITY FOR STUDENTS TO SCHOOLS NAMED HAND TAKE PART IN HISTORY GRAMMY SIGNATURE The DPS Board of Education is an- SCHOOL FINALIST nouncing the Presidential Inaugura- Carstens El- tion of Barack Obama and Dr. Martin Three DPS High Schools were ementary School Luther King, Jr. Holiday Creative recently selected as finalist in the received a spe- Expression Contest in recognition of GRAMMY Signature Schools cial visit from several of their the work of Dr. King and the promise program! Detroit School of Arts, ‘angels’ before the Thanksgiving of Senator Obama. 49 winners will Renaissance and Southeastern holiday. Mark Wagner, of Mark be selected in the contest, and all will are among a total of 31 schools Wagner Enterprises and several receive the prize of a lifetime-an all from around the country up for of his employees along with some expense paid trip to the inauguration the award. The grand prize win- youth, delivered enough turkeys of the Nation’s 44th president! Every ning school will receive a grant for every family at Carstens! They DPS student in grades 1 through 12 is ranging from $1000 up to $10,000 were thanked in a special assembly eligible to submit an entry choosing to be used towards their schools in which Vilanda Prograis’ 4th and from several categories – essay, poem, music department. The GRAMMY 5th graders thanked him with the music/Rap, power point /video or art- Signature School program is spon- following words: work. -

Reforming and Improving the Detroit Public Schools, Council

Reforming and Improving the Detroit Public Schools: Report of the Strategic Support Teams of the Council of the Great City Schools Submitted to the Detroit Public Schools By the Council of the Great City Schools 2008 Reforming and Improving the Detroit Public Schools ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Council of the Great City Schools thanks the many individuals who contributed to this project to reform and improve the Detroit Public Schools. Their efforts and commitment were critical to our ability to present the district with the best possible proposals. First, we thank General Superintendent of Schools Dr. Connie Calloway. It is not easy to ask for the kind of review that a project such as this entails. It takes leadership, courage, openness, and an uncompromising commitment to the city’s children. She has those qualities in abundance. Second, we thank the Board of Education of the Detroit Public Schools for supporting this effort and meeting with our teams to discuss issues and challenges facing the district. We hope this report proves useful as the board leads the district through this critical period. Third, we thank staff members and teachers in the Detroit Public Schools, who provided all the time, documents, and data that the Council team needed to do its work. Their openness was critical to our understanding of the challenges faced by the Detroit school system. Fourth, we thank the many individuals, groups, organizations, and associations with which we met. Our only regret is that we were unable to meet with everyone who we know had something valuable to contribute. Fifth, the Council thanks the school districts and organizations that contributed staff to this effort. -

The School District of the City of Detroit's Use of Title I, Part a Funds

The School District of the City of Detroit’s Use of Title I, Part A Funds Under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 FINAL AUDIT REPORT ED-OIG/A05H0010 July 2008 Our mission is to promote the efficiency, U.S. Department of Education effectiveness, and integrity of the Office of Inspector General Department's programs and operations. NOTICE Statements that managerial practices need improvements, as well as other conclusions and recommendations in this report, represent the opinions of the Office of Inspector General. Determinations of corrective action to be taken, including the recovery of funds, will be made by the appropriate Department of Education officials in accordance with the General Education Provisions Act. In accordance with the Freedom of Information Act (5 U.S.C. § 552), reports issued by the Office of Inspector General are available to members of the press and general public to the extent information contained therein is not subject to exemptions in the Act. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL AUDIT SERVICES Chicago/Kansas City/Dallas Audit Region July 18, 2008 Michael P. Flanagan Superintendent of Public Instruction Michigan Department of Education 608 West Allegan Street P.O. Box 30008 Lansing, MI 48909 Dear Mr. Flanagan: Enclosed is our final audit report, Control Number ED-OIG/A05H0010, entitled The School District of the City of Detroit’s Use of Title I, Part A Funds Under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. This report incorporates the comments you provided in response to the draft report. If you have any additional comments or information that you believe may have a bearing on the resolution of this audit, you should send them directly to the following Department of Education official, who will consider them before taking final Departmental action on this audit: Kerri L.