The Conquest of New Granada, Being the Life Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

José-Ignacio Avellaneda Navas Vió a España En 1539

RESEÑAS ffiSTORIA estudiar la historia del sufragio. Algo Jiménez de Quesada, no sólo la prime Antón de Olalla, alférez. similar ocurrió recientemente en la Ar ra por su antigüedad, sino por la im Hemán Pérez de Quesada, alguacil gentina, donde la transición hacia la portancia de las gentes que la confor mayor. democracia ha estimulado los estudios maron. Con Quesada llegaron, en efec Juan de San Martín, contador y electorales. En ambos países, la histo to, hombres que después se destacarían capitán. riografía electoral ha visto avances en el Nuevo Reino de Granada como Gonzalo Suárez Rendón. capitán. significativos. La experiencia de Co conquistadores, funcionarios, políticos Juan Tafur, soldado de a caballo. lombia parece ser todo lo contrario: o simplemente encomenderos. Otros Hemán Venegas, soldado de a frente a unas elecciones recurrentes, los volverían a España con sus riquezas. Esas caballo. historiadores han preferido pasarlas por condiciones de liderazgo fueron perci Albarracín viajó con Quesada, alto. Por supuesto que ha habido excep bidas por el gobernador Pedro Femández Belalcázar y Federman a España en ciones. Y hay indicios de un creciente de Lugo, el organizador de la hueste, 1539. Parece que nunca volvió. Juan de interés. En su último libro -Entre La quien nombró capitanes a algunos de Céspedes fue alcalde, regidor, teniente legitimidad y la violencia, 1875-1992 ellos. Otros sobresalieron por su rique general y justicia mayor. Gómez del (Santafé de Bogotá, Editorial Nonna, za, que les permitió comprar un arcabuz Corral retomó a España en 1540 y ja 1995) -, Marco Palacios dedica nota o un caballo, lo cual les daba una más regresó. -

The Legend of Bogota S N O M M O C

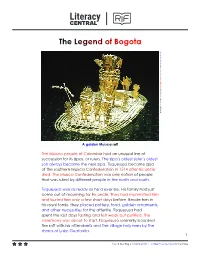

The Legend of Bogota s n o m m o C a i d e m i k i W a i v ) k r o w n w O ( ) z i t r O n á r u D o t r e b o R o i r a M ( o d r o i r a M y B A golden Muisca raft The Muisca people of Colombia had an unusual line of succession for its zipas, or rulers. The zipa’s oldest sister’s oldest son always became the next zipa. Tisquesusa became zipa of the southern Muisca Confederation in 1514 after his uncle died. The Muisca Confederation was one nation of people that was ruled by different people in the north and south. Tisquesusa was as ready as he’d ever be. His family had just come out of mourning for his uncle. They had mummified him and buried him only a few short days before. Beside him in his royal tomb, they placed pottery, food, golden ornaments, and other necessities for the afterlife. Tisquesusa had spent the last days fasting and felt weak but purified. The ceremony was about to start. Tisquesusa solemnly boarded the raft with his attendants and the village holy men by the shores of Lake Guatavita. 1 © 2018 Reading Is Fundamental • Content created by Simone Ribke The Legend of Bogota When the water was about chest-deep, Tisquesusa dropped his ceremonial robe. He let the priests cover his body in a sticky sap. Then they covered him from head to toe in gold dust until he shone and sparkled like the Sun god himself. -

Los Muiscas En Los Textos Escolares. Su Enseñanza En El Grado Sexto

LOS MUISCAS EN LOS TEXTOS ESCOLARES. SU ENSEÑANZA EN EL GRADO SEXTO LUZ ÁNGELA ALONSO MALAVER UNIVERSIDAD DISTRITAL FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE CALDAS MAESTRÍA EN EDUCACIÓN FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS Y EDUCACIÓN BOGOTÁ - OCTUBRE DE 2018 LOS MUISCAS EN LOS TEXTOS ESCOLARES. SU ENSEÑANZA EN EL GRADO SEXTO LUZ ÁNGELA ALONSO MALAVER Trabajo de grado para obtener el título de magíster en Educación Asesor: CARLOS JILMAR DÍAZ SOLER UNIVERSIDAD DISTRITAL FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE CALDAS MAESTRÍA EN EDUCACIÓN FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS Y EDUCACIÓN BOGOTÁ - OCTUBRE DE 2018 AGRADECIMIENTOS Mis más sinceros agradecimientos a los maestros de la Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, quienes desde su labor me aportaron herramientas valiosas en mi crecimiento personal e intelectual durante el desarrollo de la maestría de Educación. En especial a mi asesor, el doctor Carlos Jilmar Díaz Soler, por su paciencia, dedicación y colaboración en la realización del presente trabajo de grado. A mi familia, por su apoyo y comprensión, pero principalmente a mi madre, doña María Delfina y a mi esposo Luis Ángel, que con su amor me han dado la fuerza necesaria para crecer en mi carrera. A Dios por ser un padre amoroso, un compañero fiel y un amigo incondicional. CONTENIDO Pág. INTRODUCCIÓN 1 JUSTIFICACIÓN 5 OBJETIVOS 8 OBJETIVO GENERAL 8 OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS 8 METODOLOGÍA 9 ANTECEDENTES 12 Sobre los Muiscas, sobre los manuales y sobre la enseñanza de los Muiscas en el currículo colombiano Capítulo 1. LOS PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS. EL CASO DE LOS MUISCAS 18 1.1. Los pueblos originarios a la llegada de los europeos. Su situación 18 1.2. -

Cartagena De Indias En El Siglo Xvii Cartagena De Indias En El Siglo Xvii

editores ste libro contiene los trabajos que se presentaron en el V Simposio sobre la EHistoria de Cartagena, llevado a cabo por el Área Cultural del Banco de la Repú- blica los días 15 y 16 de septiembre de 2005. El encuentro tuvo como tema la vida de la Haroldo Calvo Stevenson ciudad en el siglo xvii, centuria que, se po- y dría decir, empezó para Cartagena en 1586 y terminó en 1697, es decir, desde el ataque de Cartagena de indias Francis Drake hasta la toma de Pointis. en el siglo xvii El siglo xvii es el periodo menos estudiado de la historiografía nacional y cartagenera. Quizás la razón estriba en que se trata de una Adolfo Meisel Roca época que no tiene los tintes heroicos de la gesta conquistadora y fundacional del siglo xvii xvi, la vistosidad de la colonia virreinal del siglo xviii, o el drama y las tristezas del xix. Llama la atención, por ejemplo, que la Histo- el siglo ria económica de Colombia editada por José Antonio Ocampo, que es el texto estándar Adolfo Meisel Roca y Haroldo Calvo Stevenson editores sobre la materia desde hace unos veinte años, se inicia con un ensayo de Germán Colmenares sobre la formación de la economía colonial y salta a un estudio de Jaime Jaramillo Uribe sobre la economía del Virreinato. La historia de Cartagena, quizás por las mismas razones, no ha sido ajena a este olvido. Cartagena de indias en banco de la república banco de la república Cartagena de Indias en el siglo xvii Cartagena de Indias en el siglo xvii Haroldo Calvo Stevenson Adolfo Meisel Roca editores cartagena, 2007 Simposio sobre la Historia de Cartagena (2005: Cartagena) Cartagena de Indias en el Siglo xvii / V Simposio sobre la Historia de Cartagena, realizado el 15 y 16 de septiembre de 2005. -

Hydraulic Chiefdoms in the Eastern Andean Highlands of Colombia

heritage Article Hydraulic Chiefdoms in the Eastern Andean Highlands of Colombia Michael P. Smyth The Foundation for Americas Research Inc., Winter Springs, FL 32719-5553, USA; [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 16 May 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 11 July 2018 Abstract: The natural and cultural heritage of the Valley of Leiva in the Eastern Colombian Andes is closely tied to the Colonial town of Villa de Leyva. The popular tourist destination with rapid economic development and agricultural expansion contrasts sharply with an environment of limited water resources and landscape erosion. The recent discovery of Prehispanic hydraulic systems underscore ancient responses to water shortages conditioned by climate change. In an environment where effective rainfall and erosion are problematic, irrigation was vital to human settlement in this semi-arid highland valley. A chiefly elite responded to unpredictable precipitation by engineering a hydraulic landscape sanctioned by religious cosmology and the monolithic observatory at El Infiernito, the Stonehenge of Colombia. Early Colonial water works, however, transformed Villa de Leyva into a wheat breadbasket, though climatic downturns and poor management strategies contributed to an early 17th century crash in wheat production. Today, housing construction, intensive agriculture, and environmental instability combine to recreate conditions for acute water shortages. The heritage of a relatively dry valley with a long history of hydraulic chiefdoms, of which modern planners seem unaware, raises concerns for conservation and vulnerability to climate extremes and the need for understanding the prehistoric context and the magnitude of water availability today. This paper examines human ecodynamic factors related to the legacy of Muisca chiefdoms in the Leiva Valley and relevant issues of heritage in an Andean region undergoing rapid socio-economic change. -

Historiografía De Las Penas Privativas De La Libertad En Colombia

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BARCELONA Tesis Doctoral Doctorado en Derecho Facultad de Derecho HISTORIOGRAFÍA DE LAS PENAS PRIVATIVAS DE LA LIBERTAD EN COLOMBIA Diego Alonso Arias Ramírez Directora de Tesis Doctora. María José Rodríguez Puerta Mayo de 2019 Firmas María José Rodríguez Puerta Diego Alonso Arias Ramírez Directora de Tesis Estudiante ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................................ 5 Capítulo I ................................................................................................................................ 13 1. CONJETURAS GENEALÓGICAS SOBRE LOS DELITOS Y LAS PENAS EN LOS PUEBLOS ABORÍGENES COLOMBIANOS ....................................................................................................................... 13 1.1. Apuntes preliminares ....................................................................................................... -

Explore-Travel-Guides-R.Pdf

Please review this travel guide on www.amazon.com Submit additional suggestions or comments to [email protected] Businesses in Colombia are constantly evolving, please send us any new information on prices, closures and any other changes to help us update our information in a timely manner. [email protected] Written and researched by Justin Cohen Copyright ©2013 by Explore Travel Guides Colombia ISBN – 978-958-44-8071-2 Map and book design by Blackline Publicidad EU Bogotá, Colombia This travel guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to share, to copy, distribute and transmit this work. Distributed by Explore Travel Guides Colombia www.gotocolombia.com [email protected] CONTENTS General Information ............................................................................. 17 Colombia Websites for Travelers .............................................................. 48 Activities in Colombia ............................................................................. 59 A Brief History of Colombia ..................................................................... 64 Bogotá .................................................................................................. 89 Outside of Bogotá ................................................................................ 153 Suesca............................................................................................. 153 Guatavita ....................................................................................... -

Systematics of Chusquea Section Chusquea, Section Swallenochloa, Section Verticillatae, and Section Serpentes (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) Lynn G

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1986 Systematics of Chusquea section Chusquea, section Swallenochloa, section Verticillatae, and section Serpentes (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) Lynn G. Clark Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Lynn G., "Systematics of Chusquea section Chusquea, section Swallenochloa, section Verticillatae, and section Serpentes (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) " (1986). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7988. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7988 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing jiages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. -

Conquista Y Descubrimiento Del Nuevo Reino De Granada, Una Anatomía De La Infidelidad.1 Susan Herman / Illinois, July1998

ARTÍCULOS ‘Cuernos’ en la cabeza de la autoridad española: Conquista y descubrimiento del Nuevo Reino de Granada, una anatomía de la infidelidad.1 Susan Herman / Illinois, July1998 Resumen also argued, the world’s first “marriage” is adulterous: Eve, as depicted in the Chapter V digression on the Fall, gets the “wander EL Carnero usa los archivos judiciales de la administración lust” (“pasea”) and has an affair with Lucifer; Adam is thus the colonial como su fuente narrativa. Este ensayo propone que la world’s first cuckold.4 metáfora que controla el texto es la “doncella huérfana”, un cuerpo desnudo de verdades no escritas todavía y que debe ser Both of these marriage allegories are enclosed in a vestida con adornos prestados antes de ser llevada ante el novio space created by an author who actively guides us through the (Felipe IV de España) y sus invitados (los lectores del texto). Este text: it opens with “Póngale aquí el dedo el lector y espéreme estudio explora cómo Rodríguez Freile construye un sistema de adelante, porque quiero acabar esta guerra [entre los caciques “comunicación digital” que les exige a los lectores asumir una de Guatavita y de Bogotá]” (IV, 74), and closes with, “Con lo posición crítica sobre los crímenes de la administración. cual podrá el lector quitar el dedo de donde lo puso, pues está entendida la ceremonia [de correr la tierra]” (V, 85).5 Whether or Palabras claves: archivos, metáfora, administración colonial not the muisca ritual is understood will be addressed below. For the moment, suffice it to say that Rodríguez Freile here engages in a system of “digital communications” that asks the reader to Abstract “walk through” the text with his fingers. -

Bibliografía

BIBLIOGRAFÍA AGUADO, Fray Pedro. Recopilación Historial. Bogotá: Medardo Rivas, [1581] 1906. ANCÍZAR, Manuel. Peregrinación de Alpha. Bogotá: Biblioteca del Banco Popular, 1972. BÁ TEMAN, Catalina y MARTÍNEZ, Andrea. Técnicas de elaboración de las pictografías ubicadas en el área de curso del río Farfacá. Bogotá, Tesis de Grado. Facultad de Restauración.Universidad Externado de Colombia. 2001. BECERRA,José Virgilio. Arte Precolombino Pinturas Rupestres. Duitama: Editorial de la CECSO. 1990 BECERRA,José Virgilio. "Sociedades agroalfareras tempranas en el altiplano cundiboyacense. Síntesis investigativa". En: RODRÍGUEZ,]. V (Ed.): Los chibchas: adaptación y diversidad en los Andes orientales de Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional-Colciencias, 2001. BECERRA, José Virgilio. Sociedades Agroalfareras tempranas en el altiplano Cundiboyacense. En: RODRÍGUEZ,].V (Ed.): Los chibchas: Adaptación y diversidad en Los Andes orientales de Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional-COLCIENCIAS, 2001. BOADA, Ana María. Asentamientos indígenas en el valle de La Laguna (Samacá - Boyacá-). Bogotá: Banco de la República, 1987. BORJAG.,Jaime Humberto. Rostros y rastros del demonio en la Nueva Granada. Indios, negros, judíos, mujeres y otras huestes de Satanás. Bogotá: Editorial Ariel, 1998. BOTIVA c., Álvaro. Arte rupestre en Cundinamarca. Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación. Bogotá: Gobernación de Cundinamarca, Instituto Departamental de Cultura, Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, Fondo Mixto de Cultura de Cundinamarca, 2000. BROADBENT, Silvia. "Los chibchas: Organización sociopolítica". Bogotá: Serie Latinoamericana N. o 5. Facultad de Sociología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 1964. BROADBENT, Silvia. Investigaciones arqueológicas en territorio chibcha. Bogotá: Universidad de Los Andes, 1965. BROADBENT, Silvia. Stone-Roofed Chambers in Chibcha Territory.Berkeley, California, 1965. I pictografías, moyas y rocas del Farfacá de Tunjay Motavita f 141 CARDALE DE SCHRlMPFF, Marianne. -

Lorenzo's Devil: Allegory and History in Juan Rodríguez Freile And

ENSAYOS Lorenzo’s Devil: Allegory and History in Juan Rodríguez Freile and Fray Pedro Simón Alberto Villate–Isaza / St. Olaf College Abstract Juan Rodríguez Freile’s El carnero, written in 1636, is a historical account of the conquest of modern–day In this article I read the allegorical and historical elements Colombia, well known for its salacious anecdotes and contained in the episode of Lorenzo, a colonial subject gruesome crimes of passion. In Julie Greer Johnson’s who deceives an indigenous priest by impersonating words, such unconventional historical events introduce the devil, as presented in two seventeenth-century texts, “incongruent elements which hint at the work’s ironic Juan Rodríguez Freile’s El carnero and Fray Pedro interpretation of the history of the region” (Satiric View Simón’s Noticias historiales de las conquistas de Tierra 168).1 These features of the text have been appropriately Firme en las Indias Occidentales. I examine how the related to Freile’s identity as a white Creole often in Lorenzo story, which seeks to promote the providential opposition to Spanish colonial institutions.2 Fray Pedro character of the conquest, ultimately fails to do so, Simón’s Noticias historiales de las conquistas de Tierra portraying deceitful tactics that destabilize Spanish Firme en las Indias Occidentales, the first volume of imperial ideology and call into question the Crown’s which was published in 1627, is a lesser-known historical authority in the territory. account of the conquest of the territory now comprised Keywords: Rodríguez Freile, El carnero, Pedro Simón, by Colombia and Venezuela. Simón deals less with the Noticias historiales, seventeenth–century colonial corruption of colonial society, and concentrates more historiography on the heroic deeds of the conquistadors and missionary priests who colonized the region. -

Rufino Gutierrez

BIBLIOTECA DE HISTORIA NACIONAL VOLUMEN XXVIII i$ 9 RUFINO GUTIERREZ IMPRENTA NACIONAL 1920 / BIBLIOTECA DE HISTORIA HAdONAL Fundadores: PEDRO n . ISAfiEZ y EDUARDO POSADA VOLÚMENES PUBLICADOS í Volumen i—La Patria Boba. ,, n— El Precursor. ,, m —Vida de Herrán. ,, iv —Los Comuneros.' ,, v—Recopilación Historial. ,, vi—La Convención de Ocaña. ,, vil—El Tribuno de 1810, ,, viii—Relaciones de Mando. ,, ix —Obras de Caldas. ,, x—Crónicas de Bogotá, tomo l.° ,, xi—Crónicas de Bogotá, tomo 2.° ,, xii—Crónicas de Bogotá, tomo 3.° ,, xm —El 20 de Julio. v ,, xiv—Biografía de José María Córdoba. ,, xv—Cartas de Caldas. v ,, x v i—Bibliografía Bogotana. ,, xvii—Vida de Márquez, tomo l9 ,, xvm —Vida de Márquez, tomo 29 ,, xx—Páginas de Historia Diplomática. ,, x x i—Vida de Miranda. ,, xxii—Epistolario de Rufino Cuervo, tomo l9 ,, xxiii—Epistolario de Rufino Cuervo, tomo29 ,, xxvi'" Historia de los Ferrocarriles en Colombia. ,, xxvii—Biografía de Salvador Córdoba. ,, xxvm —Monografías. REGLAMENTO DE LA ACADEMIA CAPÍTULO X Artículo 51. En las obras que la Academia acepte y publique, cada autor será responsable de sus asertos y opiniones; el instituto lo será solamente de que las obras son acreedoras a la luz pública. Parágrafo. El anterior artículo se insertará a la cabeza de las obras que la Academia patrocine, y como permanente en el Boletín, PROLOGO Ha querido mi distinguido amigo don Rufino Gutié rrez que presente yo a los lectores este'importantísimo libro suyo sobre la historia y la geografía de Colombia. Corres pondo con la mayor buena voluntad, ya que otra cosa no puedo ofrecer, al singular honor que me dispensa.