Hantavirus Infection Reporting on 2014 Data Retrieved from Tessy* on 19 November 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art19961.Pdf

Surveillance and outbreak reports A five-year perspective on the situation of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and status of the hantavirus reservoirs in Europe, 2005–2010 P Heyman ([email protected])1, C S Ceianu2, I Christova3, N Tordo4, M Beersma5, M João Alves6, A Lundkvist7, M Hukic8, A Papa9, A Tenorio10, H Zelená11, S Eßbauer12, I Visontai13, I Golovljova14, J Connell15, L Nicoletti16, M Van Esbroeck17, S Gjeruldsen Dudman18, S W Aberle19, T Avšić-Županc20, G Korukluoglu21, A Nowakowska22, B Klempa23, R G Ulrich24, S Bino25, O Engler26, M Opp27, A Vaheri28 1. Research Laboratory for Vector-borne Diseases and National Reference Laboratory for Hantavirus Infections, Brussels, Belgium 2. Cantacuzino Institute, Vector-Borne Diseases Laboratory, Bucharest, Romania 3. National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Sofia, Bulgaria 4. Unit of the Biology of Emerging Viral Infections (UBIVE), Institut Pasteur, Lyon, France 5. Department of Virology, Erasmus University Hospital, Rotterdam, the Netherlands 6. Centre for Vectors and Infectious Diseases Research (CEVDI), National Institute of Applied Sciences (INSA), National Institute of Health Dr. Ricardo Jorge, Águas de Moura, Portugal 7. Swedish Institute for Communicable Disease Control (SMI), Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden 8. Clinical Centre, University of Sarajevo, Institute of Clinical Microbiology, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 9. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Medicine, Thessaloniki, Greece 10. Arbovirus and Imported Viral Disease Unit, National Centre for Microbiology, Institute for Health Carlos III, Majadahonda, Spain 11. Institute of Public Health, Ostrava, Czech Republic 12. Department of Virology and Rickettsiology, Bundeswehr Institute for Microbiology, Munich, Germany 13. National Centre for Epidemiology, Budapest, Hungary 14. -

SHORT REPORT Recent Increase in Prevalence of Antibodies to Dobrava-Belgrade Virus (DOBV) in Yellow-Necked Mice in Northern Italy

Epidemiol. Infect. (2015), 143, 2241–2244. © Cambridge University Press 2014 doi:10.1017/S0950268814003525 SHORT REPORT Recent increase in prevalence of antibodies to Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV) in yellow-necked mice in northern Italy A. RIZZOLI1†, V. TAGLIAPIETRA1*†,R.ROSÀ1,H.C.HAUFFE1, G. MARINI1, L. VOUTILAINEN2,3,T.SIRONEN2,C.ROSSI1,D.ARNOLDI1 3 AND H. HENTTONEN 1 Fondazione Edmund Mach – Research and Innovation Centre, San Michele all’Adige, Italy 2 Department of Virology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 3 Finnish Forest Research Institute, Vantaa, Finland Received 3 September 2014; Final revision 17 November 2014; Accepted 21 November 2014; first published online 19 December 2014 SUMMARY Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV) is the most pathogenic hantavirus in Europe with a case-fatality rate of up to 12%. To detect changes in risk for humans, the prevalence of antibodies to DOBV has been monitored in a population of Apodemus flavicollis in the province of Trento (northern Italy) since 2000, and a sudden increase was observed in 2010. In the 13-year period of this study, 2077 animals were live-trapped and mean hantavirus seroprevalence was 2·7% (S.E. = 0·3%), ranging from 0% (in 2000, 2002 and 2003) to 12·5% (in 2012). Climatic (temperature and precipitation) and host (rodent population density, rodent weight and sex, and larval tick burden) variables were analysed using Generalized Linear Models and multi-model inference to select the best model. Climatic changes (mean annual precipitation and maximum temperature) and individual body mass had a positive effect on hantavirus seroprevalence. Other possible drivers affecting the observed pattern need to be studied further. -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea. -

Euroroundups

Euroroundups S i t u at i o n o f h a n t a v i r u S i n f e c t i o n S a n d haemorrhagic f e v e r w i t h r e n a l S y n d r o m e in eu r o p e a n c o u n t r i e S a S o f de c e m b e r 2006 P Heyman ([email protected])1, A Vaheri2, the ENIVD members 1. Research Laboratory for Vector-Borne Diseases, National Reference Centre for Hantavirus Infections, Queen Astrid Military Hospital, Brussels, Belgium 2. Department of Virology, Haartman Institute, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Hantavirus infections are widely distributed in Europe with the countries, Slovenia) their epidemiology was relatively well studied. exception of the far north and the Mediterranean regions. The In large areas of Europe, however, hantavirus infections and HFRS underlying causes of varying epidemiological patterns differ among have not been studied systematically. In many countries the regions: in western and central Europe epidemics of haemorrhagic number of infections has been on the increase in recent years fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) caused by hantavirus infections (Table 2). The European Network for diagnostics of Imported Viral follow mast years with increased seed production by oak and beech Diseases (ENIVD, http://www.enivd.de) has conducted a survey of trees followed by increased rodent reproduction. In the northern hantavirus infections and HFRS in order to learn more about the regions, hantavirus infections and HFRS epidemics occur in three epidemiological features and public health impact and discuss to four year cycles and are thought to be driven by prey - predator factors that influence the occurrence of the disease. -

Report by the Republic of Slovenia on the Implementation of The

ACFC/SR (2000) 4 REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1, OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL EXPLANATION ABOUT DRAWING UP THE REPORT __________4 PART I _____________________________________________________________6 General information______________________________________________________ 6 Brief historical outline and social arrangement _______________________________ 6 Basic Economic Indicators ________________________________________________ 6 Recent general statements _________________________________________________ 7 Status of International Law________________________________________________ 8 The Protection of National Minorities and the Romany Community ______________ 9 Basic demographic data__________________________________________________ 11 Efficient measures for achieving the general goal of the Framework Convention __ 12 PART II ___________________________________________________________13 Article 1_______________________________________________________________ 13 Article 2_______________________________________________________________ 14 Article 3_______________________________________________________________ 16 Article 4_______________________________________________________________ 18 Article 5_______________________________________________________________ 26 Article 6_______________________________________________________________ 31 Article 7_______________________________________________________________ 37 Article 8_______________________________________________________________ -

Namenkundliche Informationen

Namenkundliche Informationen 95 / 96 Herausgegeben von Ernst Eichler, Karlheinz Hengst und Dietlind Krüger Leipziger Universitätsverlag 2009 Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons-BY 3.0 Deutschland Lizenz. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/ Hergestellt mit Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft. Herausgegeben im Auftrage der Philologischen Fakultät der Universität Leipzig und der Gesellschaft für Namenkunde e. V. von Ernst Eichler, Karlheinz Hengst und Dietlind Krüger. Redaktionsbeirat: Angelika Bergien, Friedhelm Debus, Karl Gutschmidt, Gerhard Koß, Hans Walther und Walter Wenzel Redaktionsassistenz: Daniela Ohrmann Layout und Satz: Daniela Ohrmann Druck: Druckerei Hensel, Leipzig Anschrift der Redaktion: Beethovenstraße 15, 04107 Leipzig Erschienen im Leipziger Universitätsverlag GmbH, 2009 Augustusplatz 10 / 11, 04109 Leipzig Bezugsmöglichkeiten über den Verlag Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. ISSN: 0943-0849 Inhalt A Aufsätze / Articles Hans Walther Leipzigs Name im Lichte seiner Frühüberlieferung / The Name Leipzig in Early Written Records . 11 Karlheinz Hengst Der Name Leipzig als Hinweis auf Gegend mit Wasserreichtum / The Name Leipzig as an Indication of an Area with Abundant Amounts of Water . 21 Ernst Eichler Onomastischer Vergleich: Deutsch ‒ Tschechisch / Onomastical Comparison: German ‒ Czech . 33 Karlheinz Hengst Bemerkungen aus sprachhistorischer Sicht zur ältesten Urkunde von Greiz und ihrer landesgeschichtlichen Auswertung / Notes on the Oldest Document of Greiz and its Regional Historical Analysis from a Historical-linguistic Viewpoint . 37 Walter Wenzel Umstrittene Deutungen Lausitzer Ortsnamen / Controversial Analysis of Lusation Place Names . 55 Vincent Blanár Proper Names In the Light of Theoretical Onomastics . 89 Christian Todenhagen Names as a Potential Source for Conflict. A Case in Point from the USA: How Germantown, Glenn County, California, became Artois . 159 Harald Bichlmeier Einige grundsätzliche Überlegungen zum Verhältnis von Indogermanistik resp. -

Serbian Soldiers of World War I Who Died in the Netherlands

Tatjana Vendrig, Fabian Vendrig, John M. Stienen Serbian soldiers of World War I who died in the Netherlands BrusselBerlijnPekingMontevideoAbuDhabiTelAvivLondenIstanboelAlmatyBangkokHelsinkiSanJoséParamariboAnkaraSaoPauloPretoriaBangkokMilaanBamakoHoustonHa Tatjana Vendrig, Fabian Vendrig, John M. Stienen Serbian soldiers of World War I who died in the Netherlands Драга Лепа, ако не добијеш скоро моја Dear Lepa, if you don’t get my letters писма, знај да нисам више жив. Јер soon, you have to know that I am not волијем и умрети сада него доцније alive anymore. Because I’d rather die слеп ићи по свету. Ћорав човек не than wander around like a blind person. ради у руднику. Ако се избавим одавде A blind man doesn’t work in the mine. If јавићу ти. Само ми је жао што још I escape from here, I will inform you. My нисам добио слику дечију и твоју, да only regret is that I still haven’t got the бих могао видети и Ружицу. children’s and your photo, so that I could also see Ružica. Excerpt from a letter from Đorđe Vukosavljević (born in Kragujevac, Serbia) who was a non- commissioned officer in the Serbian army. The letter was written on 30th June 1918 in Soltau (Germany). Đorđe died on 22nd January 1919 in Nieuw-Milligen (the Netherlands). 6 Foreword Dear reader, After the publications about Jenny Merkus, Jacob Colyer and the diary of Arius van Tienhoven, this brochure completes a series on Dutch-Serbian relations over the past century. A team of voluntary researchers has documented the identities of 91 Serbian soldiers who died in the Netherlands during or as a consequence of the First World War. -

Masaryk University Brno Faculty of Education

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Grammatical Interference in the Language of Czech and Polish Speakers of English Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Radek Vogel, Ph.D. Bc. et Bc. Magdalena Kyzlinková Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci diplomovou vypracovala samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. Brno, 22. července 2018 …….………………… Magdalena Kyzlinková Acknowledgement In the first place, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the supervisor of my diploma thesis, Mgr. Radek Vogel, Ph.D., for his guidance, valued help and professional advice not only throughout writing this work, but also during the whole course of my studies at Masaryk University. Furthermore, I would like to thank my siblings and their families, my partner and my mother for their patience, motivation and support. Finally, special thanks are also given to all the Polish and Czech participants without whom the research could not have been conducted. Anotace Tato diplomová práce se zabývá gramatickou interferencí v jazyce českých a polských mluvčích angličtiny. Práce je rozdělena do dvou hlavních částí, teoretické a praktické. Teoretická část se skládá ze tří kapitol. První kapitola se pokouší nastínit nejdůležitější historické kontakty tří porovnávaných zemí s hlavním zaměřením na polsko-anglické a česko-anglické vztahy. Druhá kapitola je věnována popisu typologie jako lingvistické vědy, je zde nastíněn její historický vývoj, a v neposlední řadě se zaměřuje jak na typologickou, tak genealogickou klasifikaci jazyků. -

TRADITIONAL HOUSE NAMES AS PART of CULTURAL HERITAGE Klemen Klinar, Matja` Ger{I~ R a N I L K

Acta geographica Slovenica, 54-2, 2014, 411–420 TRADITIONAL HOUSE NAMES AS PART OF CULTURAL HERITAGE Klemen Klinar, Matja` Ger{i~ R A N I L K N E M E L K The P re Smôlijo farm in Srednji Vrh above Gozd Martuljek. Klemen Klinar, Matja` Ger{i~, Traditional house names as part of cultural heritage Traditional house names as part of cultural heritage DOI: http: //dx.doi.org/ 10.3986/AGS54409 UDC: 811.163.6'373.232.3(497.452) COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT: Traditional house names are a part of intangible cultural heritage. In the past, they were an important factor in identifying houses, people, and other structures, but modern social processes are decreas - ing their use. House names preserve the local dialect with its special features, and their motivational interpretation reflects the historical, geographical, biological, and social conditions in the countryside. This article comprehensively examines house names and presents the methods and results of collecting house names as part of various projects in Upper Carniola. KEY WORDS: traditional house names, geographical names, cultural heritage, Upper Carniola, onomastics The article was submitted for publication on November 15, 2012. ADDRESSES: Klemen Klinar Northwest Upper Carniola Development Agency Spodnji Plav` 24e, SI – 4270 Jesenice, Slovenia Email: klemen.klinarragor.si Matja` Ger{i~ Anton Melik Geographical Institute Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts Gosposka ulica 13, SI – 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Email: matjaz.gersiczrc -sazu.si 412 Acta geographica Slovenica, 54-2, 2014 1 Introduction »Preserved traditional house names help determine historical and family conditions, social stratification and interpersonal contacts, and administrative and political structure. -

Country Report on Conditions for Green and Sustainable Building Slovenia

BUILD SEE The Divide Between the EU Indicators and their Practical Implementation in the Green Construction and Eco‐Social Requalification of residential areas in South East Europe Working Package 3 (WP3) COUNTRY REPORT ‐ Slovenia ‐ Project Partner: BSC Kranj NAVA ARHITEKTI / Ljubljana COUNTRY REPORT SLOVENIA April 2014 1 Index Introduction 4 Aims of the project 4 Description of the methodology A brief outline of Republic of Slovenia Presentation of Gorenjska region – field of processing Chapter 1: PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ISSUES 10 1.1 INTRODUCTION 10 1.2 CURRENT SITUATION 12 1.2.1. Introduction of the strategic planning in Slovenia 1.2.2. Land use and spatial development 18 1.2.3. Implementation of Spatial Planning in Slovenia 19 1.2.4. Supporting legislation fields for improvements of urban regeneration 24 1.2.5. A comparison of spatial planning and implementation documentation at a local level 24 1.3 BEST PRACTICE AND SWOT ANALYSIS 26 1.4 RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENT (tools) 26 1.5 CONCLUSIONS REGARDING ADMINISTRATION ISSUES 30 Chapter 2: SOCIAL ISSUES 32 2.1 INTRODUCTION 32 2.2 CURRENT SITUATION 33 2.2.1 Economical aspects 33 2.2.2. Social aspects ‐ demographic, migration, population projection 33 2.2.3. Built form and the sense of place 35 2.2.4. Housing 35 2.2.5. Why we need an “Active Citizen”? 38 2.3 BEST PRACTICE AND SWOT ANALYSIS 39 2.4 RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 39 2.5 CONCLUSIONS REGARDING SOCIAL ISSUES 40 COUNTRY REPORT SLOVENIA April 2014 2 Chapter 3: BUILDING INNOVATION ISSUES 41 3.1 INTRODUCTION 41 3.1.1 Interventions in the built environment in Slovenia 41 3.1.2 Founding of sustainable construction in Slovenia 42 3.1.3 Problematic of sustainable development agendas in Slovenia 42 3.2 CURRENT SITUATION 42 3.2.1 Energy politics 42 3.2.2. -

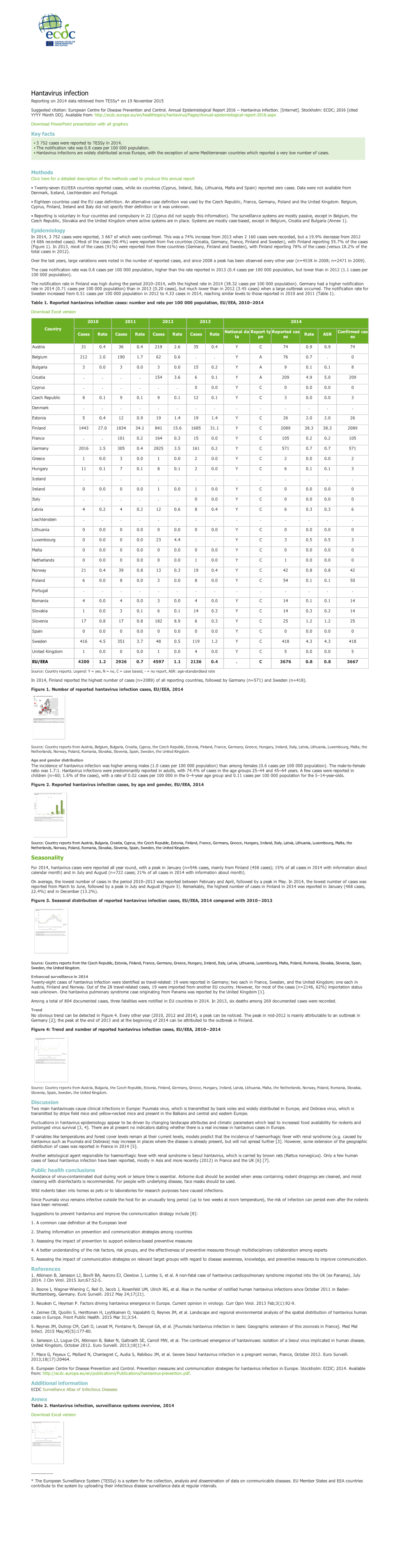

Hantavirus Infection

SURVEILLANCE REPORT Hantavirus infection Annual Epidemiological Report for 2019 Key facts • For 2019, 29 countries reported 4 046 cases of hantavirus infection (0.8 cases per 100 000 population), mainly caused by Puumala virus (98%). • During the period 2015–2019, the overall notification rate fluctuated between 0.4 and 0.8 cases per 100 00 population, with no obvious long-term trend. • In 2019, two countries (Finland and Germany) accounted for 69% of all reported cases. • In the absence of a licensed vaccine, prevention mainly relies on rodent control, avoidance of contact with rodent excreta (urine, saliva or droppings), and properly cleaning and disinfecting areas contaminated by rodent excreta. Introduction Hantaviruses are rodent-borne viruses that can be transmitted to humans by contact with faeces/urine from infected rodents or dust containing infective particles. There are several hantaviruses, with different geographical distributions and they cause different clinical diseases. Each hantavirus is specific to a rodent host. Three main clinical syndromes can be distinguished after hantavirus infection: haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), mainly caused by Seoul, Puumala and Dobrava viruses which are prevalent in Europe; nephropathia epidemica, a mild form of HFRS caused by Puumala virus, and hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome, which may be caused by Andes virus, Sin Nombre virus, and several others prevalent in the Americas. The clinical presentation varies from sub-clinical, mild, and moderate-to-severe, depending in part on the causative agent of the disease [1]. In most cases, humans are infected through direct contact with infected rodents or their excreta. There is no curative treatment and eliminating or minimising contact with rodents is the best way to prevent infection. -

Italian Language in Education in Slovenia

The ITalIan language In education In SlovenIa European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by Italn Ia The Italian language in education in Slovenia c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | t ca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Albanian; the Albanian language in education in Italy and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy, the Province of Asturian; the Asturian language in education in Spain Fryslân, and the municipality of Leeuwarden. Basque; the Basque language in education in France (2nd ed.) Basque; the Basque language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) Breton; the Breton language in education in France (2nd ed.) Catalan; the Catalan language in education in France © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Catalan; the Catalan language in education in Spain and Language Learning, 2012 Cornish; the Cornish language in education in the UK Corsican; the Corsican language in education in France (2nd ed.) ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Croatian; the Croatian language in education in Austria 1st edition Frisian; the Frisian language in education in the Netherlands (4th ed.) Gaelic; the Gaelic language in education in the UK The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, Galician; the Galician language in education in Spain provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European German; the German language in education in Alsace, France (2nd ed.) German; the German language in education in Belgium Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning.