Gender Asymmetries in Slovak Personal Nouns Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHPT Open Register

Tested Negative for the PHPT Gene INTERNATIONAL OPEN REGISTER Last Saved: 19 January 2020 PRIMARY HYPERPARATHYROID DISEASE (PHPT) (Animal Health Diagnostic Centre - College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University USA) Below is a list of Keeshond dogs, sorted by their country, of residence, with their national Kennel Club registration numbers, their sire and dam, and giving the date when they were DNA tested for the dominantly inherited Hyperparathryoid disease. The result of the test can be either 'Positive' for the PHPT gene or 'Negative' for the PHPT gene. There is no carrier state for a dominantly inherited gene and it only takes one Positive parent to pass the gene onto approximately 50% of their progeny. The progeny of two gene negative parents, irrespective of whether they are Hereditarily Negative (Negative by Descent) or Tested Negative, will be Hereditarily Negative (Negative by Descent). Where any of the dogs listed have been imported and their country of origin has been confirmed this is shown in parenthesis, in preference to the standard (Imp) identifier. Further information can be found on www.keeshoundhealth.com Dog Name Reg/Stud No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Result AUSTRALIA (AU) CALIVALE HEARTBREAKER ANKC 2100029582 21/03/98 B Vendorfe Styled N the USA Velsen Made In Heaven Sep 08 Negative CALIVALE IM TOO SEXY ANKC 2100163691 16/05/03 B Bargeway Hurricane (GB) Calivale September Morn Sep 08 Negative CALIVALE JUST DO IT ANKC 2100257279 27/07/07 D Rymist Dealers Choice Velsen Undercover Angel Sep 08 Negative CALIVALE MRS -

Freedom House

7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 Slovakia 88 FREE /100 Political Rights 36 /40 Civil Liberties 52 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 88 /100 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. TOP https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/freedom-world/2020 1/15 7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House Overview Slovakia’s parliamentary system features regular multiparty elections and peaceful transfers of power between rival parties. While civil liberties are generally protected, democratic institutions are hampered by political corruption, entrenched discrimination against Roma, and growing political hostility toward migrants and refugees. Key Developments in 2019 In March, controversial businessman Marian Kočner was charged with ordering the 2018 murder of investigative reporter Ján Kuciak and his fiancée. After phone records from Kočner’s cell phone were leaked by Slovak news outlet Aktuality.sk, an array of public officials, politicians, judges, and public prosecutors were implicated in corrupt dealings with Kočner. Also in March, environmental activist and lawyer Zuzana Čaputová of Progressive Slovakia, a newcomer to national politics, won the presidential election, defeating Smer–SD candidate Maroš Šefčovič. Čaputová is the first woman elected as president in the history of the country. Political Rights A. Electoral Process A1 0-4 pts Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 TOP Slovakia is a parliamentary republic whose prime minister leads the government. There is also a directly elected president with important but limited executive powers. In March 2018, an ultimatum from Direction–Social Democracy (Smer–SD), a https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/freedom-world/2020 2/15 7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House junior coalition partner, and center-right party Most-Híd, led to the resignation of former prime minister Robert Fico. -

Unter Europäischen Sozialdemokraten – Wer Weist Den Weg Aus Der Krise? | Von Klaus Prömpers Von Der Partie

DER HAUPTSTADTBRIEF 23. WOCHE AM SONNTAG 09.JUNI 2019 DIE KOLUMNE Rückkehr zu außenpolitischen Fundamenten AM SONNTAG Die Reise des Bundespräsidenten nach Usbekistan zeigt, wie wichtig die Schnittstelle zwischen Europa und Asien ist | Von Manfred Grund und Dirk Wiese Sonstige Vereinigung ie wichtig Zentralasien für Mirziyoyev ermutigen, „auf diesem Weg Europa ist, hat Frank-Walter entschlossen weiterzugehen“. Steinmeier WSteinmeier früh erkannt. Im und Mirziyoyev kannten sich bereits vom November 2006 bereiste er als erster Au- Berlin-Besuch des usbekischen Präsidenten GÜNTER ßenminister aus einem EU-Mitgliedsland im Januar 2019 – dem ersten eines usbeki- BANNAS BERND VON JUTRCZENKA/DPABERND VON alle fünf zentralasiatischen Staaten. Er schen Staatsoberhaupts seit 18 Jahren. PRIVAT wollte damals ergründen, wie die Euro- Die Bedeutung Zentralasiens für Europa päische Union mit der Region zusammen- hat seit 2007 weiter zugenommen. Zugleich ist Kolumnist des HAUPTSTADTBRIEFS. Bis März 2018 war er Leiter der Berliner arbeiten könne, die – so war ihm schon hat sich die geopolitische Schlüsselregion – Redaktion der Frankfurter Allgemeinen damals klar – „einfach zu wichtig ist, als Usbekistan zeigt es – grundlegend verändert. Zeitung. Hier erinnert er an die politisch dass wir sie an den Rand unseres Wahr- Die EU-Kommission und die Hohe Vertrete- vielgestaltige Gründungsphase der nehmungsspektrums verdrängen.“ Ein rin der EU für Außen- und Sicherheitspoli- Grünen vor 40 Jahren. halbes Jahr später nahm die EU auf Initi- tik haben diesen Entwicklungen Rechnung ative der deutschen Ratspräsidentschaft getragen und am 15. Mai eine überarbeitete die Strategie „EU und Zentralasien – eine Zentralasienstrategie vorgestellt. Unter dem nfang kommenden Jahres wer- Partnerschaft für die Zukunft“ (kurz: EU- Titel „New Opportunities for a Stronger Part- Aden die Grünen ihrer Grün- Zentralasienstrategie) an. -

Art19961.Pdf

Surveillance and outbreak reports A five-year perspective on the situation of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and status of the hantavirus reservoirs in Europe, 2005–2010 P Heyman ([email protected])1, C S Ceianu2, I Christova3, N Tordo4, M Beersma5, M João Alves6, A Lundkvist7, M Hukic8, A Papa9, A Tenorio10, H Zelená11, S Eßbauer12, I Visontai13, I Golovljova14, J Connell15, L Nicoletti16, M Van Esbroeck17, S Gjeruldsen Dudman18, S W Aberle19, T Avšić-Županc20, G Korukluoglu21, A Nowakowska22, B Klempa23, R G Ulrich24, S Bino25, O Engler26, M Opp27, A Vaheri28 1. Research Laboratory for Vector-borne Diseases and National Reference Laboratory for Hantavirus Infections, Brussels, Belgium 2. Cantacuzino Institute, Vector-Borne Diseases Laboratory, Bucharest, Romania 3. National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Sofia, Bulgaria 4. Unit of the Biology of Emerging Viral Infections (UBIVE), Institut Pasteur, Lyon, France 5. Department of Virology, Erasmus University Hospital, Rotterdam, the Netherlands 6. Centre for Vectors and Infectious Diseases Research (CEVDI), National Institute of Applied Sciences (INSA), National Institute of Health Dr. Ricardo Jorge, Águas de Moura, Portugal 7. Swedish Institute for Communicable Disease Control (SMI), Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden 8. Clinical Centre, University of Sarajevo, Institute of Clinical Microbiology, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 9. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Medicine, Thessaloniki, Greece 10. Arbovirus and Imported Viral Disease Unit, National Centre for Microbiology, Institute for Health Carlos III, Majadahonda, Spain 11. Institute of Public Health, Ostrava, Czech Republic 12. Department of Virology and Rickettsiology, Bundeswehr Institute for Microbiology, Munich, Germany 13. National Centre for Epidemiology, Budapest, Hungary 14. -

Exploring Your Surname Exploring Your Surname

Exploring Your Surname As of 6/09/10 © 2010 S.C. Meates and the Guild of One-Name Studies. All rights reserved. This storyboard is provided to make it easy to prepare and give this presentation. This document has a joint copyright. Please note that the script portion is copyright solely by S.C. Meates. The script can be used in giving Guild presentations, although permission for further use, such as in articles, is not granted, to conform with prior licenses executed. The slide column contains a miniature of the PowerPoint slide for easy reference. Slides Script Welcome to our presentation, Exploring Your Surname. Exploring Your Surname My name is Katherine Borges, and this presentation is sponsored by the Guild of One- Name Studies, headquartered in London, England. Presented by Katherine Borges I would appreciate if all questions can be held to the question and answer period at Sponsored by the Guild of One-Name Studies the end of the presentation London, England © 2010 Guild of One-Name Studies. All rights reserved. www.one-name.org Surnames Your surname is an important part of your identity. How did they come about This presentation will cover information about surnames, including how they came Learning about surnames can assist your about, and what your surname can tell you. In addition, I will cover some of the tools genealogy research and techniques available for you to make discoveries about your surname. Historical development Regardless of the ancestral country for your surname, learning about surnames can assist you with your genealogy research. Emergence of variants Frequency and distribution The presentation will cover the historical development of surnames, the emergence of variants, what the current frequency and distribution of your surname can tell you DNA testing to make discoveries about the origins, and the use of DNA testing to make discoveries about your surname. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2012, No.27-28

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: l Guilty verdict for killer of abusive police chief – page 3 l Ukrainian Journalists of North America meet – page 4 l A preview: Soyuzivka’s Ukrainian Cultural Festival – page 5 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXX No. 27-28 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 1-JULY 8, 2012 $1/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine at Euro 2012: Yushchenko announces plans for new political party Another near miss by Zenon Zawada Special to The Ukrainian Weekly and Sheva’s next move KYIV – Former Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko was known for repeatedly saying that he hates politics, cre- by Ihor N. Stelmach ating the impression that he was doing it for a higher cause in spite of its dirtier moments. SOUTH WINSOR, Conn. – Ukrainian soccer fans Yet even at his political nadir, Mr. Yushchenko still can’t got that sinking feeling all over again when the game seem to tear away from what he hates so much. At a June 26 officials ruled Marko Devic’s shot against England did not cross the goal line. The goal would have press conference, he announced that he is launching a new evened their final Euro 2012 Group D match at 1-1 political party to compete in the October 28 parliamentary and possibly inspired a comeback win for the co- elections, defying polls that indicate it has no chance to qualify. hosts, resulting in a quarterfinal match versus Italy. “One thing burns my soul – looking at the political mosa- After all, it had happened before, when Andriy ic, it may happen that a Ukrainian national democratic party Shevchenko’s double header brought Ukraine back won’t emerge in Ukrainian politics for the first time in 20 from the seemingly dead to grab a come-from- years. -

SHORT REPORT Recent Increase in Prevalence of Antibodies to Dobrava-Belgrade Virus (DOBV) in Yellow-Necked Mice in Northern Italy

Epidemiol. Infect. (2015), 143, 2241–2244. © Cambridge University Press 2014 doi:10.1017/S0950268814003525 SHORT REPORT Recent increase in prevalence of antibodies to Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV) in yellow-necked mice in northern Italy A. RIZZOLI1†, V. TAGLIAPIETRA1*†,R.ROSÀ1,H.C.HAUFFE1, G. MARINI1, L. VOUTILAINEN2,3,T.SIRONEN2,C.ROSSI1,D.ARNOLDI1 3 AND H. HENTTONEN 1 Fondazione Edmund Mach – Research and Innovation Centre, San Michele all’Adige, Italy 2 Department of Virology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 3 Finnish Forest Research Institute, Vantaa, Finland Received 3 September 2014; Final revision 17 November 2014; Accepted 21 November 2014; first published online 19 December 2014 SUMMARY Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV) is the most pathogenic hantavirus in Europe with a case-fatality rate of up to 12%. To detect changes in risk for humans, the prevalence of antibodies to DOBV has been monitored in a population of Apodemus flavicollis in the province of Trento (northern Italy) since 2000, and a sudden increase was observed in 2010. In the 13-year period of this study, 2077 animals were live-trapped and mean hantavirus seroprevalence was 2·7% (S.E. = 0·3%), ranging from 0% (in 2000, 2002 and 2003) to 12·5% (in 2012). Climatic (temperature and precipitation) and host (rodent population density, rodent weight and sex, and larval tick burden) variables were analysed using Generalized Linear Models and multi-model inference to select the best model. Climatic changes (mean annual precipitation and maximum temperature) and individual body mass had a positive effect on hantavirus seroprevalence. Other possible drivers affecting the observed pattern need to be studied further. -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

Miss Universe Mexico, Andrea Meza, Crowned 69Th Miss Universe in Inspiring Televised Show Featuring an Electrifying Performance

MISS UNIVERSE MEXICO, ANDREA MEZA, CROWNED 69TH MISS UNIVERSE IN INSPIRING TELEVISED SHOW FEATURING AN ELECTRIFYING PERFORMANCE BY GRAMMY- NOMINATED ARTIST LUIS FONSI Clips from the show and images can be found at press.missuniverse.com HOLLYWOOD, FL (May 17, 2021) – Miss Universe Mexico Andrea Meza was crowned Miss Universe live on FYI™ and Telemundo last night from the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, Florida. Andrea will use her year as Miss Universe to advocate for women’s rights and against gender-based violence. After a beautiful National Costume Competition, rounds of interviews, a preliminary competition and the live Finals, Andrea was crowned with the beautiful Mouawad Power of Unity Crown, presented to her by outgoing Miss Universe 2019 Zozibini Tunzi, who now holds the title for the longest-ever reigning Miss Universe. “I am so honored to have been selected among the 73 other amazing women I stood with tonight,” said Miss Universe Andrea Meza. “It is a dream come true to wear the Miss Universe crown, and I hope to serve the world through my advocacy for equality in the year to come and beyond.” Andrea Meza, 26, is from Chihuahua City, and represented her home country, Mexico, as Miss Universe Mexico, in the 69th annual Miss Universe competition. Andrea has a degree in software engineering, and is an activist, and currently works closely with the Municipal Institute for Women, which aims to end gender-based violence. She is also a certified make-up artist and model, who is passionate about being active and living a healthy lifestyle. -

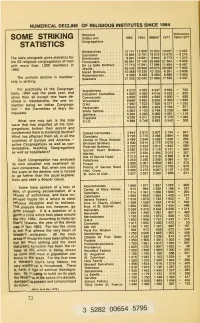

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

“English Name” Use Among Chinese and Taiwanese Students at an Australian University

NAMING RIGHTS: THE DIALOGIC PRACTICE OF “ENGLISH NAME” USE AMONG CHINESE AND TAIWANESE STUDENTS AT AN AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITY Julian Owen Harris SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS University of Melbourne By the beginning of the 21st century, Australia had become one of the world’s top 5 providers of international education services along with the USA, the UK, Germany and France. Since 2001, China has provided the largest proportion of international students to Australia, a tenfold growth in numbers from 1994 to 2003. The overwhelming majority of Chinese and Taiwanese students studying in Australian universities use what are typically called “English names”. The use of such names differs from the practice in Hong Kong of providing a new born with what might be termed an official English name as part of the full Chinese name that appears on his or her birth certificate and/or passport. By comparison, these English names as used by Chinese and Taiwanese are “unofficial” names that do not appear on the bearer’s passport, birth certificate or university administrative procedurals or degree certificates. Their use is unofficial and largely restricted to spoken interactions. Historically, English names used to be typically given to an individual by their English teacher; such classroom “baptisms” invariably occurred in Chinese or Taiwanese geographical settings. The term ‘baptisms’ and ‘baptismal events’ are drawn from Rymes (1996) and her research towards a theory of naming as practice. Noting that ‘serial mononymy is relatively uncommon in the literature on naming practices, Rymes (1996, p. 240) notes that more frequent are instances of individuals experiencing ‘a series of baptismal events in which [they] acquire and maintain different names for different purposes.’ Noting these cases among the Tewa of Arizona on Tanna in Vanuatu, Rymes (1996, pp.