Engaging Chicago's Diverse Communities in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mccormick Place Lakeside Center Brochure

LAKESIDE CENTER LAKESIDE CENTER MEETING ROOMS LEVEL 2 LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 LEVEL 3 Room Sq. Ft. Dimensions Ceiling Height Theater School Room Banquet E250 966 36' 9" x 25' 8" 10' 0" † – – E251 955 36' 8" x 25' 5" 12' 0" 50 48 48 Dock Door C1 E252 2,289 40' 8" x 56' 1" 12' 1" 50 48 48 Roll Up Doors 3-10 E253 6,678 53' 1" x 126' 0" 13' 11" 744 333 384 E253a 1,840 53' 1" x 36' 0" 13' 11" 189 90 80 Dock Doors A - F E253b 1,612 53' 1" x 30' 0" 13' 11" 173 78 64 Dock Dock E253c 1,612 53' 1" x 30' 0" 13' 11" 173 78 64 Freight Door Doors Doors 29' 0" 29' 0" E253d 1,613 53' 1" x 30' 0" 13' 11" 173 78 64 29' 0" 29' 0" B3-B9 D1-D7 To E254 1,190 49' 4" x 22' 6" 8' 4" † – – Soldier Field Parking E255 1,439 57' 1" x 25' 2" 14' 1" 153 72 56 E256 1,445 57' 7" x 25' 0" 14' 1" 153 72 56 EF 2 Gate 34 Gate 35 E257 1,214 49' 1" x 22' 7" 12' 0" 50 48 40 EF 1 EF2 EF1 Roll Up Roll Up E258 2,718 56' 1" x 48' 4" 11' 11" 252 135 128 Level One Area Loading Dock Door 2 Door 11 EF1 E259 1,353 51' 9" x 26' 0" 12' 0" 138 60 64 Roll Up Door G EF2 LEVEL 4 E260 1,034 39' 6" x 26' 1" 12' 0" 102 51 40 E261 1,032 39' 7" x 26' 0" 12' 0" 102 51 40 Hall D E262 1,039 39' 8" x 26' 1" 12' 0" 102 51 40 Gate 33 Dock Hall E 300,000 sq. -

Cook County Hazard Mitigation Plan – Lemont Annex

COOK COUNTY MULTI-JURISDICTIONAL HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN VOLUME 2 - Municipal Annexes Lemont Annex FINAL July 2019 Prepared for: Cook County Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 69 W. Washington St., Suite 2600 Chicago, Illinois 60602 Toni Preckwinkle William Barnes President Executive Director Cook County Board of Commissioners Cook County Department of Homeland Security & Emergency Management VOLUME 2: COOK COUNTY HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN – LEMONT ANNEX Table of Contents Hazard Mitigation Point of Contact .............................................................................................................. 2 Jurisdiction Profile ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Capability Assessment .................................................................................................................................. 5 Jurisdiction-Specific Natural Hazard Event ................................................................................................. 10 Hazard Risk Ranking .................................................................................................................................... 12 Mitigation Strategies and Actions ............................................................................................................... 13 New Mitigation Actions .......................................................................................................................... 16 Ongoing -

Opposition Behaviour Against the Third Wave of Autocratisation: Hungary and Poland Compared

European Political Science https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00325-x SYMPOSIUM Opposition behaviour against the third wave of autocratisation: Hungary and Poland compared Gabriella Ilonszki1 · Agnieszka Dudzińska2 Accepted: 4 February 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Hungary and Poland are often placed in the same analytical framework from the period of their ‘negotiated revolutions’ to their autocratic turn. This article aims to look behind this apparent similarity focusing on opposition behaviour. The analysis demonstrates that the executive–parliament power structure, the vigour of the extra- parliamentary actors, and the opposition party frame have the strongest infuence on opposition behaviour, and they provide the sources of diference between the two country cases: in Hungary an enforced power game and in Poland a political game constrain opposition opportunities and opposition strategic behaviour. Keywords Autocratisation · Extra-parliamentary arena · Hungary · Opposition · Parliament · Party system · Poland Introduction What can this study add? Hungary and Poland are often packed together in political analyses on the grounds that they constitute cases of democratic decline. The parties in governments appear infamous on the international, particularly on the EU, scene. Fidesz1 in Hungary has been on the verge of leaving or being forced to leave the People’s Party group due to repeated abuses of democratic norms, and PiS in Poland2 is a member of 1 The party’s full name now reads Fidesz—Hungarian Civic Alliance. 2 Abbreviation of Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice). * Gabriella Ilonszki [email protected] Agnieszka Dudzińska [email protected] 1 Department of Political Science, Corvinus University of Budapest, 8 Fővám tér, Budapest 1093, Hungary 2 Institute of Sociology, University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, 00-927 Warsaw, Poland Vol.:(0123456789) G. -

Italian-Americans: the Dons of Suburbia Rotella, Carlo

Italian-Americans: the dons of suburbia Rotella, Carlo . Boston Globe ; Boston, Mass. [Boston, Mass]11 Oct 2010: A.9. ProQuest document link ABSTRACT Since World War II, the path of least resistance toward middle-class status has led to the suburbs, and Italian- Americans have enthusiastically made their way along it. [...] formulaic stories about Italian-American gangsters have helped Italianness sustain its cachet as a dominant ethnic identity in this country. FULL TEXT I'VE NEVER had much of an opinion either way about Columbus Day, but it seems like a good occasion to consider the important role played by people of Italian descent in the settlement and development of a new world in America. I mean the suburbs, of course. There isn't a more suburban ethnic group in this country than Italian- Americans, and it's worth considering what that might mean. First, the numbers. In an analysis of the 2000 census, the sociologists Richard Alba and Victor Nee found that 73.5 percent of Italian-Americans who lived in metropolitan areas lived in the suburbs, a percentage that tied them for first place with Polish-Americans, with Irish-Americans and German-Americans coming in third and fourth. And 91.2 percent of Italian-Americans lived in metropolitan areas, a higher percentage than for any other non-Hispanic white ethnic group. (Polish-Americans came in second at 88.3 percent.) Put those two statistics together, and Italian-Americans can make a pretty strong claim to the title of pound-for-pound champions of suburbanization. That would seem to suggest a history of assimilation and success. -

Newsletter, Vol 32 No 1, Summer 2001

ASLH NEWSLETTER .¿-fY FOÞ. n' ' '{q s"W.z-OO."' uæà5 PRESIDENT-ELECT Robert A. Gordon Yale UniversitY SECRETARY-TREASURER Walter F, Pratt, Jr. University of Notre Dame and Annual Meetin "Eallot l{ ÙoLUME 32, No. 1 sumtel2ool "- i lÈl Ð --- 1 2001 Annu¡lMeetlng,Chicago ' " " ' " " B¡llot.. """"""'3 NomlneeforPresldent'elect """3 NomineesforBo¡rdofDlrectors,' """"4 8 Nomlnees for Bo¡rd ofDlrectors (Gr¡düate student positlon) " " " " " NomlneesforNomlnatlngCommittee ' """"""'9 Annoutrcements ""'l0 Paull.MurPbYPrlze """""10 J.WillardHurstSummerlnstituteln LegalHistory " ' ' ' " " ll Law&HßtoryRevlew.. """"12 StudiesinleirlHistory """"12 series I 3 universlty of Texas Law Librrry lnaugurrtes Legrl Hlstory Publication ' ' H-Law. """14 of cnlifornia' vlslting scholars, center for the study of Law and socle$, university Berkeley Draftprogram..,..' lnformatlon¡boutlocatarrrngements """""30 34 Child Care for the meeting " " " UNCPressTltles ,.,.., """35 2001 Annual Meetlng. Chic¡go November 8'l l, The Society's thirty-first annual meeting will be held Thursday-Sunday, meeting are bound in the center in Chicago. Regisiration materials and the draft program for the Note th0t ofthis newsletter. Be sure to retum the registration forms by the dates indicated' 9-10t30. th.re ,rlll b, , ,.t of nrorrar sotloor on sundry motoint. No"emb.t I ltrt. hdicate on the prs In rdditlon. plGsse n0le these soeclal event$. for whlch y0ü 0re asked to reglstr¡tion form your Planned attendance: Thursdry, November 8th 2:30-4;30 pm, Chicago Historicrl Soclety (self'guided tour) tgr : ëi , $ì, , åì,' l¡. 5;30-7r00 l)rì, ASLII rcccDti0n, Àllcgr.0 ll0tel Thc Socic{y is rtlso ùlosl ¡¡p|reciatlle oIfhc lìltallcial suppot t ptovùlctl by lhe,Ânrcrictitt lì, B¡r lìoùndafioD, DePl¡rìl l-aiv Soltool, Joh¡ Marshall Líìu'School, NoÍh\\'cslent 1..¡v School, ntlrl I'rid¡y, Novc¡ltDcr' 9rr' ofChicago Larv 8ll the [hiversily School. -

Allyson Hobbs Cv June 2020

June 2020 ALLYSON VANESSA HOBBS Department of History, Stanford University 450 Serra Mall, Building 200, Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected] allysonhobbs.com CURRENT POSITIONS Stanford University, Associate Professor, Department of History, September 2008 - present Director, African and African American Studies, January 2017 – present Kleinheinz Family University Fellow in Undergraduate Education, 2019-2024 Affiliated with: American Studies (Committee-in-Charge Member) Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (Core Affiliated Faculty) Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (Researcher) Center for Institutional Courage (Research Advisor) Ethics in Society (Faculty Affiliate) Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (Program Committee) Masters in Liberal Arts Program (Faculty Advisor) Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research (Faculty Fellow) Stanford Center for Law and History (Affiliated Member) Urban Studies (Faculty Affiliate) The New Yorker.com, Contributing Writer, November 2015 – present https://www.newyorker.com/contributors/allyson-hobbs EDUCATION University of Chicago, Ph.D., History, March 2009, with distinction Dissertation: “When Black Becomes White: The Problem of Racial Passing in American Life” Committee: Professors Thomas Holt (Chair; History, University of Chicago), George Chauncey (History, Yale University), Jacqueline Stewart (Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago) Harvard University, A.B., Social Studies, June 1997, magna cum laude Received magna cum laude distinction on senior honors -

Local School Board-

Bulk Rate U.S. Postage ..N1LES. 50 CENTS DEC97 PAID N PERCOPY Edition NILES PBLlC LIBRARY Bugle News 7400 CALI WELL RILES IL 6Y714 8746N. SHERMER RD., NILES, IL 60714 VOL 4t, NO. t9 - - - - Restaurañts, Polls open from 6a.m. to 7 pm. - From the schóols cater to HiHais 50th - Left byRonema.y Tirio 'She doesn't look 50." That Local school - was the assessmenl of tt-yeat- board- Händ old -Joe Oliver, a sixth grader in . by Bud Besser Men. Warneke's class at the Fietd School is Park Ridge, wheit Hit- A Nilesjtetelóphoned bey Rodham Clinton visit6d her electionsonTuesday last week to Complain about alma mater en the day- after her Mayor Blase's new sign cri- - 5øthbirthday. bylEonemaryTirlo Candidates arelining op for the lizisg AT&T for its tower at Oliver said that he and his Sbanne Kniechbaum of Skokie Maine Township District 207 .: Howard Street äsd Milwau- classmates were excitedand Nob. 4 election when they will who has bene u poet-time intInte- Four four-year terms will be vie fon malay school hoard vacan- - kee Ave. Public Works'peo- proud lo have a IO-minute goes- loralOaklon. - filled in Ihn upcoming school : t1e took dowu the sige os the tien-answersession with the FinsI cies lhroughool suburban corn- Further information aboul the bnardetectiosin disleict 207. east side of Milwaakee Ave. Lady teIlte school aodiloniam be- munition. candidates is available from Pro- The three incumbents muaisg - - and replaced it with a new fore she addressed the entire sta- OaktonCommunity Cnllege - fessor Frank Fonsino, Chair of are Iris Friedlich, Ralph M. -

2023 Capital Improvement Program

CITY OF CHICAGO 2019 - 2023 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM OFFICE OF BUDGET & MANAGEMENT Lori E. Lightfoot, MAYOR 2019 - 2023 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM T ABLE OF CONTENTS 2019-2023 Capital Improvement Program (CIP) .............................................................................1 CIP Highlights & Program…………………...………......................................................................2 CIP Program Descriptions.................................................................................................................6 2019 CIP Source of Funds & Major Programs Chart......................................................................10 2019-2023 CIP Source of Funds & Major Programs Chart..............................................................12 2019-2023 CIP Programs by Fund Source.......................................................................................14 Fund Source Key..............................................................................................................................45 2019-2023 CIP by Program by Project……………………………...………………….................47 2019-2023 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM The following is an overview of the City of Chicago’s Capital Improvement Program (CIP) for the years 2019 to 2023, a five-year schedule of infrastructure investment that the City plans to make for continued support of existing infrastructure and new development. The City’s CIP addresses the physical improvement or replacement of City-owned infrastructure and facilities. Capital improvements are -

Poland's 2019 Parliamentary Election

— SPECIAL REPORT — 11/05/2019 POLAND’S 2019 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse Warsaw Institute POLAND’S 2019 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION Held on October 13, 2019, Poland’s general election is first and foremost a success of democracy, as exemplified by crowds rushing to polling stations and a massive rise in voter turnout. Those that claimed victory were the govern- ment groups that attracted a considerable electorate, winning in more constitu- encies across the country they ruled for the past four years. Opposition parties have earned a majority in the Senate, the upper house of the Polish parliament. A fierce political clash turned into deep chasms throughout the country, and Poland’s political stage reveals polarization between voters that lend support to the incumbent government and those that question the authorities by manifest- ing either left-liberal or far-right sentiments. Election results Poland’s parliamentary election in 2019 attrac- try’s 100-seat Senate, the upper house of the ted the attention of Polish voters both at home parliament, it is the Sejm where the incum- and abroad while drawing media interest all bents have earned a majority of five that has over the world. At stake were the next four a pivotal role in enacting legislation and years in power for Poland’s ruling coalition forming the country’s government2. United Right, led by the Law and Justice party (PiS)1. The ruling coalition won the election, The electoral success of the United Right taking 235 seats in Poland’s 460-seat Sejm, the consisted in mobilizing its supporters to a lower house of the parliament. -

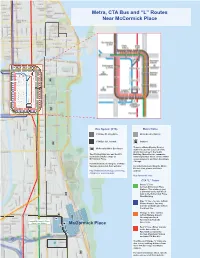

Metra, CTA Bus and “L” Routes Near Mccormick Place

Metra, CTA Bus and “L” Routes Near McCormick Place Bus System (CTA) Metra Trains CTA Bus #3, King Drive Metra Electric District CTA Bus #21, Cermak Stations There is a Metra Electric District McCormick Place Bus Stops station located on Level 2.5 of the Grand Concourse in the South The #3 King Drive bus and the #21 Building. Metra Electric commuter Cermak bus makes stops at railroad provides direct service within McCormick Place. seven minutes to and from downtown Chicago. For information on riding the CTA Bus System, please visit their website: For information on riding the Metra Electric Line, please visit their http://www.transitchicago.com/riding_ website: cta/service_overview.aspx http://metrarail.com/ CTA “L” Trains Green “L” line Cermak-McCormick Place Station - This station is just a short two and a half block walk to the McCormick Place West Building Blue “L” line - Service to/from O’Hare Airport. You may transfer at Clark/Lake to/from the Green line. Orange “L” line - Service to/from Midway Airport. You may transfer at Roosevelt to/from the Cermak-McCormick Place Green Line. Green Line Station McCormick Place Red “L” line - Either transfer to the Green Line at Roosevelt or exit at the Cermak-Chinatown Station and take CTA Bus #21 The Blue and Orange “L” trains are also in easy walking distance from most CTA Bus stops and Metra stations. For more information about specific routes, please visit their website:. -

Naród Polski Bi-Lingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America a Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities

Naród Polski Bi-lingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America A Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities June 2015 - Czerwiec 2015 No. 6 - Vol. CXXIX www.PRCUA.org Zapraszamy PRCUA PRESIDENT PRCUA CELEBRATES MAY 3rd do czytania JOSEPH A. DROBOT, JR. POLISH CONSTITUTION DAY stron 15-20 AWARDED Chicago, IL - The Polish Roman Catholic Union of America w j`zyku was proud to participate in the May Third Polish Constitution HALLER SWORDS MEDAL Day Parade that marched down Dearborn Street in Chicago on polskim. Saturday, May 2, 2015. For the 124th time, Polish Americans in Chicago honored the Cleveland, OH – The Polish May 3rd Constitution that was adopted by the Parliament of the Roman Catholic Union of America Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1791. It was the first Father congratulates PRCUA National democratic constitution in Europe and the second in the World is someone President Joseph A. Drobot, Jr. who after the U.S. Constitution. who holds you was awarded the Haller Swords Medal Mike (“Coach K”) Krzyzewski, coach of the Duke University by PAVA Post 152 on May 16, 2015. basketball team and the U.S. national basketball team was this when you cry, The award ceremony took place at the scolds you year’s Grand Marshal of the parade. Cardiologist Dr. Fred Leya, Polish American Cultural Center in and Dr. John Jaworski - well known Polonia activist and when you break Cleveland, OH, during the 80th President of PRCUA Soc. #800 - were Vice Marshals. The motto the rules, Anniversary Celebration of the Polish of the parade was "I Love Poland and You Should Too." shines with pride Army Veterans Association (PAVA) PRCUA was well represented in this year’s parade. -

2012 Appropriation Ordinance 10.27.11.Xlsx

2012 Budget Appropriations 3 4 Table of Contents Districtwide 8 Humboldt Park……………...…....………….…… 88 Districtwide Summary 9 Kedvale Park……………...…....………….…….. 90 Communications……………….....….……...….… 10 Kelly (Edward J.) Park……………...…....……91 Community Recreation ……………..……………. 11 Kennicott Park……………...…....………….…… 92 Facilities Management - Specialty Trades……………… 29 Kenwood Community Park……………...…. 93 Grant Park Music Festival………...……….…...… 32 La Follette Park……………...…....………….…… 94 Human Resources…………..…….…………....….. 33 Lake Meadows Park ……………...…....………96 Natural Resources……………….……….……..….. 34 Lakeshore……………...…....………….…….. 97 Park Services - Permit Enforcement 38 Le Claire-Hearst Community Center……… 98 Madero School Park……………...…....……… 99 Central Region 40 McGuane Park……………...…....………….…… 100 Central Region Parks 41 McKinley Park……………………………....…… 103 Central Region – Summary ...……...……................. 43 Moore Park……………...…....………….…….. 105 Central Region – Administration……….................... 44 National Teachers Academy……………...… 106 Altgeld Park………………………………………… 46 Northerly Island……………...…....………….… 108 Anderson Playground Park……….……...………….. 47 Orr Park………………………………..…..…..… 109 Archer Park……...................................................... 48 Piotrowski Park……………...…....………….… 110 Armour Square Park……........................................... 49 Pulaski Park……………...…....………….…….. 113 Augusta Playground……........................................... 50 Seward Park ……………...…....………….…….. 114 Austin Town Hall……...............................................