Study of Solanum Elaeagnifolium, a Successful Invasive Plant from C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3250 Ríos Mediterráneos De Caudal Permanente Con Glaucium Flavum

1 PRESENTACIÓN 3250 RÍOS MEDITERRÁNEOS DE CAUDAL PERMANENTE CON GLAUCIUM FLAVUM COORDINADOR Manuel Toro AUTORES Manuel Toro, Santiago Robles e Inés Tejero 2 TIPOS DE HÁBITAT DE AGUA DULCE / 3250 RÍOS MEDITERRÁNEOS DE CAUDAL PERMANENTE CON GLAUCIUM FLAVUM Esta ficha forma parte de la publicación Bases ecológicas preliminares para la conservación de los tipos de hábitat de interés comunitario en España, promovida por la Dirección General de Medio Natural y Política Forestal (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino). Dirección técnica del proyecto Rafael Hidalgo. Realización y producción Coordinación general Elena Bermejo Bermejo y Francisco Melado Morillo. Coordinación técnica Juan Carlos Simón Zarzoso. Colaboradores Presentación general: Roberto Matellanes Ferreras y Ramón Martínez Torres. Edición: Cristina Hidalgo Romero, Juan Párbole Montes, Sara Mora Vicente, Rut Sánchez de Dios, Juan García Montero, Patricia Vera Bravo, Antonio José Gil Martínez y Patricia Navarro Huercio. Asesores: Íñigo Vázquez-Dodero Estevan y Ricardo García Moral. Diseño y maquetación Diseño y confección de la maqueta: Marta Munguía. Maquetación: Do-It, Soluciones Creativas. Agradecimientos A todos los participantes en la elaboración de las fichas por su esfuerzo, y especialmente a Antonio Camacho, Javier Gracia, Antonio Martínez Cortizas, Augusto Pérez Alberti y Fernando Valladares, por su especial dedicación y apoyo a la dirección y a la coordinación general y técnica del proyecto. Las opiniones que se expresan en esta obra son responsabilidad de los autores y no necesariamente de la Dirección General de Medio Natural y Política Forestal (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino). 3 La coordinación general del grupo 32 ha sido encargada a la siguiente institución Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas Coordinador: Manuel Toro1. -

Solanum Elaeagnifolium Cav. R.J

R.A. Stanton J.W. Heap Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. R.J. Carter H. Wu Name Lower leaves c. 10 × 4 cm, oblong-lanceolate, distinctly sinuate-undulate, upper leaves smaller, Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. is commonly known oblong, entire, venation usually prominent in in Australia as silverleaf nightshade. Solanum is dried specimens, base rounded or cuneate, apex from the Latin solamen, ‘solace’ or ‘comfort’, in acute or obtuse; petiole 0.5–2 cm long, with reference to the narcotic effects of some Solanum or without prickles. Inflorescence a few (1–4)- species. The species name, elaeagnifolium, is flowered raceme at first terminal, soon lateral; Latin for ‘leaves like Elaeagnus’, in reference peduncle 0.5–1 cm long; floral rachis 2–3 cm to olive-like shrubs in the family Elaeagnaceae. long; pedicels 1 cm long at anthesis, reflexed ‘Silverleaf’ refers to the silvery appearance of and lengthened to 2–3 cm long in fruit. Calyx the leaves and ‘nightshade’ is derived from the c. 1 cm long at anthesis; tube 5 mm long, more Anglo-Saxon name for nightshades, ‘nihtscada’ or less 5-ribbed by nerves of 5 subulate lobes, (Parsons and Cuthbertson 1992). Other vernacu- whole enlarging in fruit. Corolla 2–3 cm diam- lar names are meloncillo del campo, tomatillo, eter, rotate-stellate, often reflexed, blue, rarely white horsenettle, bullnettle, silver-leaf horsenet- pale blue, white, deep purple, or pinkish. Anthers tle, tomato weed, sand brier, trompillo, melon- 5–8 mm long, slender, tapered towards apex, cillo, revienta caballo, silver-leaf nettle, purple yellow, conspicuous, erect, not coherent; fila- nightshade, white-weed, western horsenettle, ments 3–4 mm long. -

Rare Plant Monitoring 2017

RARE PLANT MONITORING 2017 Ajuga pyramidalis Ophrys insectifera © Zoe Devlin What is it? In 2017, we decided to carry out a small pilot scheme on rare plant monitoring. Where experienced plant recorders had submitted recent casual records of rare plants to the Centre, they were asked if they would be willing to visit their rare plant population once a year during its flowering period and to count the total number of individuals present. The response to the scheme from the small number of recorders contacted has been overwhelming positive and it has resulted in very valuable data being collected in 2017. Data on the rare plant location, the count and additional information about the site is submitted online through a dedicated web portal set up by the Data Centre. The project was discussed and agreed with the NPWS. It is framed around the 2016 Vascular Plant Red List and is mainly focused on monitoring vulnerable, near threatened and rare least concern species. Why is it important? When assessing the national FAST FACTS 2017 conservation status of very rare species according to IUCN Red List methodology, it is recommended that 37 you use annual population count data. That’s the total number of rare plant Given the numbers of rare plant populations that were monitored in the species a country might have, this 2017 pilot information can be difficult to collect in any volume. This citizen science project relies on the generosity of 22 expert volunteers to ‘keep an eye’ on That’s the number of rare plant species rare populations near them and to that were monitored in 2017 submit standardised count data once a year. -

A Review of European Progress Towards the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2011-2020

A review of European progress towards the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2011-2020 1 A review of European progress towards the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2011-2020 The geographical area of ‘Europe’ includes the forty seven countries of the Council of Europe and Belarus: Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Republic of Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Front Cover Image: Species rich meadow with Papaver paucifoliatum, Armenia, Anna Asatryan. Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the copyright holders concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mentioning of specific companies or products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by PLANTA EUROPA or Plantlife International or preferred to others that are not mentioned – they are simply included as examples. All reasonable precautions have been taken by PLANTA EUROPA and Plantlife International to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall PLANTA EUROPA, Plantlife International or the authors be liable for any consequences whatsoever arising from its use. -

Eyre Peninsula NRM Board PEST SPECIES REGIONAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Solanum Elaeagnifolium Silverleaf Nightshade

Eyre Peninsula NRM Board PEST SPECIES REGIONAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Solanum elaeagnifolium Silverleaf nightshade INTRODUCTION Synonyms Solanum dealbatum Lindl., Solanum elaeagnifolium var. angustifolium Kuntze, Solanum elaeagnifolium var. argyrocroton Griseb., Solanum elaeagnifolium var. grandiflorum Griseb., Solanum elaeagnifolium var. leprosum Ortega Dunal, Solanum elaeagnifolium var. obtusifolium Dunal, Solanum flavidum Torr., Solanum obtusifolium Dunal Solanum dealbatum Lindley, Solanum hindsianum Bentham, Solanum roemerianum Scheele, Solanum saponaceum Hooker fil in Curtis, Solanum texense Engelman & A. Gray, and Solanum uniflorum Meyer ex Nees. Silver nightshade, silver-leaved nightshade, white horse nettle, silver-leaf nightshade, tomato weed, white nightshade, bull-nettle, prairie-berry, satansbos, silver-leaf bitter-apple, silverleaf-nettle, and trompillo, prairie berry Biology Silverleaf nightshade Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. is a seed- or vegetatively-propagated deep-rooted summer-growing perennial geophyte from the tomato family Solanaceae [1]. This multi-stemmed plant grows to one metre tall, with the aerial growth normally dying back during winter (Figure 1B). The plants have an extensive root system spreading to over two metres deep. These much branched vertical and horizontal roots bear buds that produce new aerial growth each year [2], in four different growth forms (Figure 1A): Figure 1: A. Summary of silverleaf nightshade growth patterns. from seeds germinating from spring through summer; from Source: [4]. B. Typical silverleaf nightshade growth cycle. buds above soil level giving new shoots in spring; from buds Source: [5]. at the soil surface; and from buds buried in the soil, which regenerate from roots (horizontal or vertical) [1]. Origin The life cycle of the plant is composed of five phases (Figure Silverleaf nightshade is native to northeast Mexico and 1B). -

44 * Papaveraceae 1

44 * PAPAVERACEAE 1 Dennis I Morris 2 Annual or perennial herbs, rarely shrubs, with latex generally present in tubes or sacs throughout the plants. Leaves alternate, exstipulate, entire or more often deeply lobed. Flowers often showy, solitary at the ends of the main and lateral branches, bisexual, actinomorphic, receptacle hypogynous or perigynous. Sepals 2–3(4), free or joined, caducous. Petals (0–)4–6(–12), free, imbricate and often crumpled in the bud. Stamens usually numerous, whorled. Carpels 2-many, joined, usually unilocular, with parietal placentae which project towards the centre and sometimes divide the ovary into several chambers, ovules numerous. Fruit usually a capsule opening by valves or pores. Seeds small with crested or small raphe or with aril, with endosperm. A family of about 25 genera and 200 species; cosmopolitan with the majority of species found in the temperate and subtropical regions of the northern hemisphere. 6 genera and 15 species naturalized in Australia; 4 genera and 9 species in Tasmania. Papaveraceae are placed in the Ranunculales. Fumariaceae (mostly temperate N Hemisphere, S Africa) and Pteridophyllaceae (Japan) are included in Papaveraceae by some authors: here they are retained as separate families (see Walsh & Norton 2007; Stevens 2007; & references cited therein). Synonymy: Eschscholziaceae. Key reference: Kiger (2007). External resources: accepted names with synonymy & distribution in Australia (APC); author & publication abbre- viations (IPNI); mapping (AVH, NVA); nomenclature (APNI, IPNI). 1. Fruit a globular or oblong capsule opening by pores just below the stigmas 2 1: Fruit a linear capsule opening lengthwise by valves 3 2. Stigmas joined to form a disk at the top of the ovary; style absent 1 Papaver 2: Stigmas on spreading branches borne on a short style 2 Argemone 3. -

A Biophysical and Economic Evaluation of Biological and Chemical Control Methods for Solanum Elaegnifolium

A BIOPHYSICAL AND ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF BIOLOGICAL AND CHEMICAL CONTROL METHODS FOR SOLANUM ELAEGNIFOLIUM (SILVERLEAF NIGHTSHADE) IN THE LIMPOPO PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA By Dikeledi Confidence Pitso Thesis presented for the degree of Master of Philosophy In the Department of Zoology University of Cape Town September 2010 i DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT I hereby declare that the dissertation submitted for the degree MPhil Zoology at the University of Cape Town is my own original work and has not previously been submitted to any other institution of higher education. I further declare that all sources cited and quoted are indicated and acknowledged by means of a comprehensive list of references. Dikeledi Confidence Pitso ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to give thanks to the Lord Almighty for strengthening me throughout the completion of the project, also would like to thank my mother, Malethola Pitso, for being the pillar of strength in my life, I love you mom and I dedicate this thesis to you and Amahle Pitso. To my sisters, Mpho Selai, Mphai Pitso, and Suzan Selai, thank you for words of encouragement; to a wonderful man in my life, Nhlanhla Kunene, thank you for believing in me and for showing support throughout. My friends at the ARC-PPRI, Vuyokazi April and Ayanda Nongogo, thank you for everything; to Mr and Mrs Zirk van Zyl, and Mr Koos Roos it was a pleasure working with you, you are truly great sports and thank you for opening your businesses for us to work on for this study; it is much appreciated. Most importantly, I would like to extend my thanks to my supervisors, Prof. -

Evaluation of Gratiana Spadicea (Klug, 1829) and Metriona Elatior

Evaluation of Gratiana spadicea (Klug, 1829) and Metriona elatior (Klug, 1829) (Chrysomelidae: Cassidinae) for the biological control of sticky nightshade Solanum sisymbriifolium Lamarck (Solanaceae) in South Africa. THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of Rhodes University by MARTIN PATRICK HILL December 1994 · FRONTISPIECE Top Row (Left to Right): Gratiana spadicea adults and egg case; Gratiana spadicea larvae; Gratiana spadicea pupae. Centre: Solanum sisymbriifolium (sticky nightshade). Bottom Row (Left to Right): Metriona elatior adults; Metriona elatior larvae; Metriona elatior pupae. 11 PUBLICATIONS ARISING FROM THIS STUDY Parts of the research presented in this thesis, already accepted for publication are the following: Hill, M.P., P.E. Hulley and T.Olckers 1993. Insect herbivores on the exotic w~eds Solanum elaeagnifolium Cavanilles and S. sisymbrilfolium Lamarck (Solanaceae) in South Africa. African Entomology 1: 175-182. Hill, M.P. and P.E. Hulley 1995. Biology and host range of Gratiana spadicea (Klug, 1829) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Cassidinae), a potential biological control agent for the weed Solanum sisymbriifolium Lamarck (Solanaceae) in South Africa. Biological Control, in press. Hill, M.P. and P.E. Hulley 1995. Host range extension by native parasitoids to weed biocontrol agents introduced to South Africa. Biological Control, in press. 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS lowe a huge debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Professor P.E. Hulley for his guidance, support and enthusiasm throughout this project, and.for teaching me to think things through properly. He must also be thanked for constructive comments on earlier drafts of the thesis and for allowing me to use much of his unpublished data on insects associated with native Solanum species. -

Silverleaf Nightshade

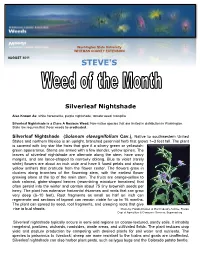

Washington State University WHITMAN COUNTY EXTENSION AUGUST 2011 STEVE'S Silverleaf Nightshade Also Known As: white horsenettle, purple nightshade, tomato weed, trompillo Silverleaf Nightshade is a Class A Noxious Weed: Non-native species that are limited in distribution in Washington. State law requires that these weeds be eradicated. Silverleaf Nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav.), Native to southwestern United States and northern Mexico is an upright, branched perennial herb that grows 1–3 feet tall. The plant is covered with tiny star like hairs that give it a silvery green or yellowish- green appearance. Stems are armed with a few slender, yellow spines. The leaves of silverleaf nightshade are alternate along the stem, have wavy margins, and are lance-shaped to narrowly oblong. Blue to violet (rarely white) flowers are about an inch wide and have 5 fused petals and showy yellow anthers that protrude from the flower center. The flowers grow in clusters along branches of the flowering stem, with the earliest flower growing alone at the tip of the main stem. The fruits are orange-yellow to dark colored, globe-shaped berries (resembling miniature tomatoes) that often persist into the winter and contain about 75 tiny brownish seeds per berry. The plant has extensive horizontal rhizomes and roots that can grow very deep (6–10 feet). Root fragments as small as half an inch can regenerate and sections of taproot can remain viable for up to 15 months. The plant can spread by seed, root fragments, and creeping roots that give rise to bud shoots. Photo by: Florida Division of Plant Industry Archive, Florida Dept of Agriculture & Consumer Services, Bugwood.org Silverleaf nightshade typically occurs in semi-arid regions on coarse-textured, sandy soils. -

Pest Risk Analysis for Solanum Elaeagnifolium and International Management Measures Proposed

Pest risk analysis for Solanum elaeagnifolium and international management measures proposed S. Brunel EPPO, 21 Bld Richard Lenoir, Paris, 75011, France; e-mail: [email protected] Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav., originating from the Americas, has been unintentionally introduced in all the other continents as a contaminant of commodities, and is considered one of the most inva- sive plants worldwide. In the Euro-Mediterranean area, it is a huge threat in North African countries. It is also present in European Mediterranean countries (France, Greece, Italy and Spain), but still has a limited distribution. Through a logical sequence of questions, pest risk analysis (PRA) assessed the probability of S. elaeagnifolium entering, establishing, spreading and having negative impacts in European and Mediterranean countries. As this assessment revealed that the entry of the pest would result in an unacceptable risk, pest risk management options were selected to prevent the introduction of the plant. Preventive measures on plants or plant products traded internationally may directly or indirectly affect international trade. According to international treaties, PRA is a technical justification of such international preventive measures. Almost all possible commodities are traded internationally, repre- unacceptable risk, pest risk management selects options to senting a value of EUR 6.5 trillion (USD 8.9 trillion) in 2004 prevent the introduction of the species or to control it. (Burgiel et al., 2006). In addition to movements of commodities, The International Standard on Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM almost 700 million people cross international borders as tourists no. 5, 2005) ‘Glossary’ defines terms used in this article such each year (McNeely, 2006). as ‘commodity’, ‘entry’, ‘introduction’, ‘establishment’, ‘wide- Movements of agricultural products and people provide a spread’. -

2859A/B 50 L/150L Poppies Papaver Rhoeas Papaveraceae Fl a ANDORRA (Spanish) 2009, Jan

Vol. 58 #4 107 ALBANIA 2008, July 30 (pair) 2859a/b 50 l/150l Poppies Papaver rhoeas Papaveraceae Fl A ANDORRA (Spanish) 2009, Jan. 17 346 32 c Daffodils Narcissus pseudonarcissus Amaryllidaceae Fl A ANTIGUA & BARBUDA 2009, Apr. 10 3034 $1.00 Peony Paeonia sp. Paeoniaceae Fl A ARGENTINA 2008, Sept. 20 2497 1 p Cherry blossoms Prunus sp. Rosaceae Fl B 2008, Sept. 27 2501 5 p Gerbera daisy, gardenia, rose Gerbera x hybrida, Gardenia sp. Rosa sp. Compositae, Rubiaceae, Rosaceae Fl A SS Z 2502 5 p Carnation, lily, delphinium Dianthus caryophyllus, Lilium auratum, Delphinium grandiflorum Caryophyllaceae, Liliaceae, Caryophyllaceae Fl A SS Z 2008, Oct. 25 2508 1 p Ceiba chodatii Bombacaceae Fl A 2509 1 p Lotus Nelumbo nucifera Nelumbaceae Fl A 2008, Dec. 13 2515 1p Forestry School 50th anniv: stylized tree T A S BAHAMAS 2009 Type of 2006, see Vol 56 #2 p55 1195B 15 c Yesterday, today & tomorrow Brunfelsia calcina Solanaceae Fl A 2009, Apr. 10 1280a-h 50 c Peonies Paeonia x hybrida Paeoniaceae Fl A MS Z BELGIUM 2009, Jan. 2 2348 1 (80c) Tulip Tulipa bakeri Liliaceae Fl A BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA 2008, July 1 628 1.50 m Water lily Nymphaea alba Nymphaeaceae Fl A 2008, Dec. 6 638 70 c Douglas fir Pseudotsuga menziesi Pinaceae T F A 639 70 c Birch Betula pendula Betulaceae T A 640 70 c Cypress Cupressus sempervirens Cupressaceae T F A BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA (Croat) 2008, Nov. 1 200 60 pf Potato tubers and plants Solanum tuberosum Solanaceae V A 201 5 m Potato flower Solanum tuberosum Solanaceae Fl A SS Vol. -

Solanum Elaeagnifolium Cavara, a New Invasive Species in the Caucasus 253-256 © Landesmuseum Für Kärnten; Download

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Wulfenia Jahr/Year: 2016 Band/Volume: 23 Autor(en)/Author(s): Zernov Alexander S., Mirzayeva Shahla N. Artikel/Article: Solanum elaeagnifolium Cavara, a new invasive species in the Caucasus 253-256 © Landesmuseum für Kärnten; download www.landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at/wulfenia; www.zobodat.at Wulfenia 23 (2016): 253–256 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Solanum elaeagnifolium Cavara, a new invasive species in the Caucasus Alexander S. Zernov & Shahla N. Mirzayeva Summary: Solanum elaeagnifolium, a native species of South America, which was not previously observed in Caucasus, is herewith newly recorded from Absheron Peninsula, Republic of Azerbaijan. Keywords: Solanum elaeagnifolium, Solanaceae, Republic of Azerbaijan, Absheron Peninsula, Caucasus, neophyte, invasive species During floristic investigations, the authors collected some specimens of invasive plants from Absheron Peninsula (Republic of Azerbaijan). Among them was a specimen that could not be identified using the ‘Keybook for the Caucasian plants’ (Grossheim 1949), ‘Flora of Absheron’ (Karjagin 1952), ‘Flora of Azerbaijan’ (Agajanov 1957), ‘Flora of Caucasus’ (Kutateladze 1967) and ‘Flora of Turkey’ (Baytop 1978). Following ‘Flora Iranica’ (Schönbeck-Temesy 1972), ‘Flora Europaea’ (Hawkes & Edmonds 1972) and ‘Flowers of Turkey’ (Pils 2006), the specimens could be identified as Solanum elaeagnifolium Cavara (Fig. 1 A–D). Geographically closest earlier recordings were made from Turkey (Pils 2006; Ilçim & Behçet 2007). Solanum elaeagnifolium Cavara, 1795, Icon. Descr. 3:22, tab. 243. Multi-stemmed, perennial herbaceous or semi-shrub plant with dense, whitish, stellate indumentum, usually with scattered, conspicuous, usually reddish spikes on stem, mature leaves and calyx; stem 50 – 80 cm or higher, erect, sparingly branched.