Pest Risk Analysis for Solanum Elaeagnifolium and International Management Measures Proposed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition AKA exotic, alien, non-native, introduced, non-indigenous, or foreign sp. National Invasive Species Council definition: (1) “a non-native (alien) to the ecosystem” (2) “a species likely to cause economic or harm to human health or environment” Not all invasive species are foreign origin (Spartina, bullfrog) Not all foreign species are invasive (Most US ag species are not native) Definition increasingly includes exotic diseases (West Nile virus, anthrax etc.) Can include genetically modified/ engineered and transgenic organisms Executive Order 13112 (1999) Directed Federal agencies to make IS a priority, and: “Identify any actions which could affect the status of invasive species; use their respective programs & authorities to prevent introductions; detect & respond rapidly to invasions; monitor populations restore native species & habitats in invaded ecosystems conduct research; and promote public education.” Not authorize, fund, or carry out actions that cause/promote IS intro/spread Political, Social, Habitat, Ecological, Environmental, Economic, Health, Trade & Commerce, & Climate Change Considerations Historical Perspective Native Americans – Early explorers – Plant explorers in Europe Pioneers moving across the US Food - Plants – Stored products – Crops – renegade seed Animals – Insects – ants, slugs Travelers – gardeners exchanging plants with friends Invasive Species… …can also be moved by • Household goods • Vehicles -

Of Physalis Longifolia in the U.S

The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review1 ,2 3 2 2 KELLY KINDSCHER* ,QUINN LONG ,STEVE CORBETT ,KIRSTEN BOSNAK , 2 4 5 HILLARY LORING ,MARK COHEN , AND BARBARA N. TIMMERMANN 2Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA 4Department of Surgery, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA 5Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review. The wild tomatillo, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related species have been important wild-harvested foods and medicinal plants. This paper reviews their traditional use as food and medicine; it also discusses taxonomic difficulties and provides information on recent medicinal chemistry discoveries within this and related species. Subtle morphological differences recognized by taxonomists to distinguish this species from closely related taxa can be confusing to botanists and ethnobotanists, and many of these differences are not considered to be important by indigenous people. Therefore, the food and medicinal uses reported here include information for P. longifolia, as well as uses for several related taxa found north of Mexico. The importance of wild Physalis species as food is reported by many tribes, and its long history of use is evidenced by frequent discovery in archaeological sites. These plants may have been cultivated, or “tended,” by Pueblo farmers and other tribes. The importance of this plant as medicine is made evident through its historical ethnobotanical use, information in recent literature on Physalis species pharmacology, and our Native Medicinal Plant Research Program’s recent discovery of 14 new natural products, some of which have potent anti-cancer activity. -

Solanum Elaeagnifolium Cav. R.J

R.A. Stanton J.W. Heap Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. R.J. Carter H. Wu Name Lower leaves c. 10 × 4 cm, oblong-lanceolate, distinctly sinuate-undulate, upper leaves smaller, Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. is commonly known oblong, entire, venation usually prominent in in Australia as silverleaf nightshade. Solanum is dried specimens, base rounded or cuneate, apex from the Latin solamen, ‘solace’ or ‘comfort’, in acute or obtuse; petiole 0.5–2 cm long, with reference to the narcotic effects of some Solanum or without prickles. Inflorescence a few (1–4)- species. The species name, elaeagnifolium, is flowered raceme at first terminal, soon lateral; Latin for ‘leaves like Elaeagnus’, in reference peduncle 0.5–1 cm long; floral rachis 2–3 cm to olive-like shrubs in the family Elaeagnaceae. long; pedicels 1 cm long at anthesis, reflexed ‘Silverleaf’ refers to the silvery appearance of and lengthened to 2–3 cm long in fruit. Calyx the leaves and ‘nightshade’ is derived from the c. 1 cm long at anthesis; tube 5 mm long, more Anglo-Saxon name for nightshades, ‘nihtscada’ or less 5-ribbed by nerves of 5 subulate lobes, (Parsons and Cuthbertson 1992). Other vernacu- whole enlarging in fruit. Corolla 2–3 cm diam- lar names are meloncillo del campo, tomatillo, eter, rotate-stellate, often reflexed, blue, rarely white horsenettle, bullnettle, silver-leaf horsenet- pale blue, white, deep purple, or pinkish. Anthers tle, tomato weed, sand brier, trompillo, melon- 5–8 mm long, slender, tapered towards apex, cillo, revienta caballo, silver-leaf nettle, purple yellow, conspicuous, erect, not coherent; fila- nightshade, white-weed, western horsenettle, ments 3–4 mm long. -

Solanum Pseudocapsicum

Solanum pseudocapsicum COMMON NAME Jerusalem cherry FAMILY Solanaceae AUTHORITY Solanum pseudocapsicum L. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE SOLPSE HABITAT Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. Terrestrial. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe FEATURES Erect, unarmed shrub, glabrous or sometimes with few branched hairs on very young shoots; stems wiry, 40~120cm tall. Petiole to 2cm long, slender. Lamina 3~12 x 1~3cm, lanceolate or elliptic-lanceolate, glossy above; margins usu. undulate; base narrowly attenuate; apex obtuse or acute. Flowers 1~several; peduncle 0~8mm long; pedicels 5~10mm long, erect at fruiting. Calyx 4~5mm long; lobes lanceolate to ovate, slightly accrescent. Corolla approx. 15mm diam., white, glabrous; lobes oblong- ovate to triangular. Anthers 2.5~3mm long. Berry 1.5~2cm diam., globose, glossy, orange to scarlet, long-persistent; stone cells 0. Seeds approx. Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. 3mm diam., suborbicular to reniform or obovoid, rather asymmetric; Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe margin thickened. (-Webb et. al., 1988) SIMILAR TAXA A plant with attractive glossy orange or red berries around 1-2 cm diameter (Department of Conservation 1996). FLOWERING October, November, December, January, February, March, April, May FLOWER COLOURS White, Yellow YEAR NATURALISED 1935 ORIGIN Eastern Sth America ETYMOLOGY solanum: Derivation uncertain - possibly from the Latin word sol, meaning “sun,” referring to its status as a plant of the sun. Another possibility is that the root was solare, meaning “to soothe,” or solamen, meaning “a comfort,” which would refer to the soothing effects of the plant upon ingestion. Reason For Introduction Ornamental Life Cycle Comments Perennial. Dispersal Seed is bird dispersed (Webb et al., 1988; Department of Conservation 1996). -

Occurrence of Horse Nettle (Solanum Carolinense L.) in North Rhine

25th German Conference on Weed Biology and Weed Control, March 13-15, 2012, Braunschweig, Germany Occurrence of horse nettle (Solanum carolinense L.) in North Rhine-Westphalia Auftreten der Carolinschen Pferdenessel (Solanum carolinense L.) in Nordrhein-Westfalen Günter Klingenhagen1*, Martin Wirth2, Bernd Wiesmann2 & Hermann Ahaus2 1Chamber of Agriculture, North Rhine-Westphalia, Plant Protection Service, Nevinghoff 40, 48147 Münster, Germany 2Chamber of Agriculture, North Rhine-Westphalia, district station Coesfeld, Borkener Straße 25, 48653 Coesfeld, Germany *Corresponding author, [email protected] DOI: 10.5073/jka.2012.434.077 Summary In autumn 2008 during corn harvest (Zea mays L.), the driver of the combine harvester spotted an unfamiliar plant species in the field. It turned out that Solanum carolinense L. was the unknown weed species. The species had overgrown 40 % of the corn field which had a size of 10.2 ha. The farmer who usually effectively controls all weeds on his field had so far not noticed the dominance of the solanaceous herb species. From his point of view, the weed must have germinated after the corn had covered the crop rows. On the affected field, corn is grown in monoculture since 1973. When the horse nettle was first spotted in October 2008, the plants had reached a height of about 120 cm, rhizomes had grown 80 cm deep and a horizontal root growth of 150 cm could be determined. In the following season (2008/2009), winter wheat was grown instead of corn on the respective field. This was followed by two years of winter rye (2009/2010 and 2010/2011). -

Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity

Natural Products Chemistry & Research Review Article Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity Morillo M1, Rojas J1, Lequart V2, Lamarti A 3 , Martin P2* 1Faculty of Pharmacy and Bioanalysis, Research Institute, University of Los Andes, Mérida P.C. 5101, Venezuela; 2University Artois, UniLasalle, Unité Transformations & Agroressources – ULR7519, F-62408 Béthune, France; 3Laboratory of Plant Biotechnology, Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tetouan, Morocco ABSTRACT Steroidal alkaloids are secondary metabolites mainly isolated from species of Solanaceae and Liliaceae families that occurs mostly as glycoalkaloids. α-chaconine, α-solanine, solamargine and solasonine are among the steroidal glycoalkaloids commonly isolated from Solanum species. A number of investigations have demonstrated that steroidal glycoalkaloids exhibit a variety of biological and pharmacological activities such as antitumor, teratogenic, antifungal, antiviral, among others. However, these are toxic to many organisms and are generally considered to be defensive allelochemicals. To date, over 200 alkaloids have been isolated from many Solanum species, all of these possess the C27 cholestane skeleton and have been divided into five structural types; solanidine, spirosolanes, solacongestidine, solanocapsine, and jurbidine. In this regard, the steroidal C27 solasodine type alkaloids are considered as significant target of synthetic derivatives and have been investigated -

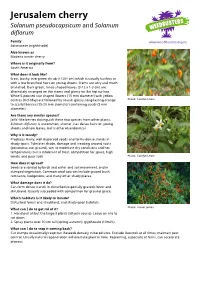

Jerusalem Cherry Solanum Pseudocapsicum and Solanum Diflorum

Jerusalem cherry Solanum pseudocapsicum and Solanum diflorum Family Solanaceae (nightshade) Also known as Madeira winter cherry Where is it originally from? South America What does it look like? Erect, bushy, evergreen shrub (<120+ cm) which is usually hairless or with a few branched hairs on young shoots. Stems are wiry and much branched. Dark green, lance-shaped leaves (3-12 x 1-3 cm) are alternately arranged on the stems and glossy on the top surface. White 5-pointed star shaped flowers (15 mm diameter) with yellow centres (Oct-May) are followed by round, glossy, long-lasting orange Photo: Carolyn Lewis to scarlet berries (15-20 mm diameter) containing seeds (3 mm diameter). Are there any similar species? Jaffa'-like berries distinguish these two species from other plants. Solanum diflorum is uncommon, shorter, has dense hairs on young shoots and new leaves, but is otherwise identical. Why is it weedy? Produces many, well dispersed seeds and forms dense stands in shady spots. Tolerates shade, damage and treading around roots (poisonous, not grazed), wet to moderate dry conditions and hot temperatures but is intolerant of frost, competition for space, high winds, and poor soils. Photo: Carolyn Lewis How does it spread? Seeds are spread by birds and water and soil movement, and in dumped vegetation. Common seed sources include grazed bush remnants, hedgerows, and many other shady places. What damage does it do? Can form dense stands in disturbed (especially grazed) forest and shrubland. Usually succeeded with competition for ground space. Which habitats is it likely to invade? Disturbed forest and shrubland, and shady open habitats. -

Eyre Peninsula NRM Board PEST SPECIES REGIONAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Solanum Elaeagnifolium Silverleaf Nightshade

Eyre Peninsula NRM Board PEST SPECIES REGIONAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Solanum elaeagnifolium Silverleaf nightshade INTRODUCTION Synonyms Solanum dealbatum Lindl., Solanum elaeagnifolium var. angustifolium Kuntze, Solanum elaeagnifolium var. argyrocroton Griseb., Solanum elaeagnifolium var. grandiflorum Griseb., Solanum elaeagnifolium var. leprosum Ortega Dunal, Solanum elaeagnifolium var. obtusifolium Dunal, Solanum flavidum Torr., Solanum obtusifolium Dunal Solanum dealbatum Lindley, Solanum hindsianum Bentham, Solanum roemerianum Scheele, Solanum saponaceum Hooker fil in Curtis, Solanum texense Engelman & A. Gray, and Solanum uniflorum Meyer ex Nees. Silver nightshade, silver-leaved nightshade, white horse nettle, silver-leaf nightshade, tomato weed, white nightshade, bull-nettle, prairie-berry, satansbos, silver-leaf bitter-apple, silverleaf-nettle, and trompillo, prairie berry Biology Silverleaf nightshade Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. is a seed- or vegetatively-propagated deep-rooted summer-growing perennial geophyte from the tomato family Solanaceae [1]. This multi-stemmed plant grows to one metre tall, with the aerial growth normally dying back during winter (Figure 1B). The plants have an extensive root system spreading to over two metres deep. These much branched vertical and horizontal roots bear buds that produce new aerial growth each year [2], in four different growth forms (Figure 1A): Figure 1: A. Summary of silverleaf nightshade growth patterns. from seeds germinating from spring through summer; from Source: [4]. B. Typical silverleaf nightshade growth cycle. buds above soil level giving new shoots in spring; from buds Source: [5]. at the soil surface; and from buds buried in the soil, which regenerate from roots (horizontal or vertical) [1]. Origin The life cycle of the plant is composed of five phases (Figure Silverleaf nightshade is native to northeast Mexico and 1B). -

Alien Plant Species in the Agricultural Habitats of Ukraine: Diversity and Risk Assessment

Ekológia (Bratislava) Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 24–31, 2018 DOI:10.2478/eko-2018-0003 ALIEN PLANT SPECIES IN THE AGRICULTURAL HABITATS OF UKRAINE: DIVERSITY AND RISK ASSESSMENT RAISA BURDA Institute for Evolutionary Ecology, NAS of Ukraine, 37, Lebedeva Str., 03143 Kyiv, Ukraine; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Burda R.: Alien plant species in the agricultural habitats of Ukraine: diversity and risk assessment. Ekológia (Bratislava), Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 24–31, 2018. This paper is the first critical review of the diversity of the Ukrainian adventive flora, which has spread in agricultural habitats in the 21st century. The author’s annotated checklist con- tains the data on 740 species, subspecies and hybrids from 362 genera and 79 families of non-native weeds. The floristic comparative method was used, and the information was gen- eralised into some categories of five characteristic features: climamorphotype (life form), time and method of introduction, level of naturalisation, and distribution into 22 classes of three habitat types according to European Nature Information System (EUNIS). Two assess- ments of the ecological risk of alien plants were first conducted in Ukraine according to the European methods: the risk of overcoming natural migration barriers and the risk of their impact on the environment. The exposed impact of invasive alien plants on ecosystems has a convertible character; the obtained information confirms a high level of phytobiotic contami- nation of agricultural habitats in Ukraine. It is necessary to implement European and national documents regarding the legislative and regulative policy on invasive alien species as one of the threats to biotic diversity. -

An Introduction to Pepino (Solanum Muricatum Aiton)

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-1, Issue-2, July -Aug- 2016] ISSN: 2456-1878 An introduction to Pepino ( Solanum muricatum Aiton): Review S. K. Mahato, S. Gurung, S. Chakravarty, B. Chhetri, T. Khawas Regional Research Station (Hill Zone), Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India Abstract — During the past few decades there has been America, Morocco, Spain, Israel and the highlands of renewed interest in pepino cultivation both in the Andean Kenya, as the pepino is considered a crop with potential for region and in several other countries, as the pepino is diversification of horticultural production (Munoz et al, considered a crop with potential for diversification of 2014). In the United States the fruit is known to have been horticultural production. grown in San Diego before 1889 and in Santa Barbara by It a species of evergreen shrub and vegetative propagated 1897 but now a days, several hundred hectares of the fruit by stem cuttings and esteemed for its edible fruit. Fruits are are grown on a small scale in Hawaii and California. The juicy, scented, mild sweet and colour may be white, cream, plant is grown primarily in Chile, New yellow, maroon, or purplish, sometimes with purple stripes Zealand and Western Australia. In Chile, more than 400 at maturity, whilst the shape may be spherical, conical, hectares are planted in the Longotoma Valley with an heart-shaped or horn-shaped. Apart from its attractive increasing proportion of the harvest being exported. morphological features, the pepino fruit has been attributed Recently, the pepino has been common in markets antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and in Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Chile and grown antitumoral activities. -

Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa Decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives

insects Review Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives Martina Kadoi´cBalaško 1,* , Katarina M. Mikac 2 , Renata Bažok 1 and Darija Lemic 1 1 Department of Agricultural Zoology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.L.) 2 Centre for Sustainable Ecosystem Solutions, School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health, University of Wollongong, Wollongong 2522, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-239-3654 Received: 8 July 2020; Accepted: 22 August 2020; Published: 1 September 2020 Simple Summary: The Colorado potato beetle (CPB) is one of the most important potato pest worldwide. It is native to U.S. but during the 20th century it has dispersed through Europe, Asia and western China. It continues to expand in an east and southeast direction. Damages are caused by larvae and adults. Their feeding on potato plant leaves can cause complete defoliation and lead to a large yield loss. After the long period of using only chemical control measures, the emergence of resistance increased and some new and different methods come to the fore. The main focus of this review is on new approaches to the old CPB control problem. We describe the use of Bacillus thuringiensis and RNA interference (RNAi) as possible solutions for the future in CPB management. RNAi has proven successful in controlling many pests and shows great potential for CPB control. Better understanding of the mechanisms that affect efficiency will enable the development of this technology and boost potential of RNAi to become part of integrated plant protection in the future. -

Host Plant Defense Produces Species-Specific Alterations to Flight Muscle Protein Structure and Flight-Related Fitness Traits of Two Armyworms Scott L

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2020) 223, jeb224907. doi:10.1242/jeb.224907 RESEARCH ARTICLE Host plant defense produces species-specific alterations to flight muscle protein structure and flight-related fitness traits of two armyworms Scott L. Portman1,*, Gary W. Felton2, Rupesh R. Kariyat3,4 and James H. Marden5 ABSTRACT expression of genes and how gene expression patterns produce Insects manifest phenotypic plasticity in their development and modifications to organ systems has applications in the fields of behavior in response to plant defenses, via molecular mechanisms ecology, conservation biology, functional genomics, population that produce tissue-specific changes. Phenotypic changes might vary dynamics and pest management, because it provides insight into between species that differ in their preferred hosts and these effects the genes and fitness traits that are being targeted by natural selection. could extend beyond larval stages. To test this, we manipulated the diet Despite the important role phenotypic plasticity plays in species of southern armyworm (SAW; Spodoptera eridania) and fall armyworm survival and evolution (Chippindale et al., 1993; Whitman and (FAW; Spodoptera frugiperda) using a tomato mutant for jasmonic acid Agrawal, 2009; Murren et al., 2015), linking environmentally plant defense pathway (def1), and wild-type plants, and then quantified induced changes to the expression patterns of specific genes (or gene expression of Troponin t (Tnt) and flight muscle metabolism of the gene suites) with distinct phenotypes has been poorly documented. adult insects. Differences in Tnt spliceform ratios in insect flight Herbivorous holometabolous insects make excellent systems to muscles correlate with changes to flight muscle metabolism and flight study phenotypic plasticity on a mechanistic level because variation in muscle output.