Solanum Muricatum) Fruit Grown in Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition AKA exotic, alien, non-native, introduced, non-indigenous, or foreign sp. National Invasive Species Council definition: (1) “a non-native (alien) to the ecosystem” (2) “a species likely to cause economic or harm to human health or environment” Not all invasive species are foreign origin (Spartina, bullfrog) Not all foreign species are invasive (Most US ag species are not native) Definition increasingly includes exotic diseases (West Nile virus, anthrax etc.) Can include genetically modified/ engineered and transgenic organisms Executive Order 13112 (1999) Directed Federal agencies to make IS a priority, and: “Identify any actions which could affect the status of invasive species; use their respective programs & authorities to prevent introductions; detect & respond rapidly to invasions; monitor populations restore native species & habitats in invaded ecosystems conduct research; and promote public education.” Not authorize, fund, or carry out actions that cause/promote IS intro/spread Political, Social, Habitat, Ecological, Environmental, Economic, Health, Trade & Commerce, & Climate Change Considerations Historical Perspective Native Americans – Early explorers – Plant explorers in Europe Pioneers moving across the US Food - Plants – Stored products – Crops – renegade seed Animals – Insects – ants, slugs Travelers – gardeners exchanging plants with friends Invasive Species… …can also be moved by • Household goods • Vehicles -

Of Physalis Longifolia in the U.S

The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review1 ,2 3 2 2 KELLY KINDSCHER* ,QUINN LONG ,STEVE CORBETT ,KIRSTEN BOSNAK , 2 4 5 HILLARY LORING ,MARK COHEN , AND BARBARA N. TIMMERMANN 2Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA 4Department of Surgery, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA 5Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review. The wild tomatillo, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related species have been important wild-harvested foods and medicinal plants. This paper reviews their traditional use as food and medicine; it also discusses taxonomic difficulties and provides information on recent medicinal chemistry discoveries within this and related species. Subtle morphological differences recognized by taxonomists to distinguish this species from closely related taxa can be confusing to botanists and ethnobotanists, and many of these differences are not considered to be important by indigenous people. Therefore, the food and medicinal uses reported here include information for P. longifolia, as well as uses for several related taxa found north of Mexico. The importance of wild Physalis species as food is reported by many tribes, and its long history of use is evidenced by frequent discovery in archaeological sites. These plants may have been cultivated, or “tended,” by Pueblo farmers and other tribes. The importance of this plant as medicine is made evident through its historical ethnobotanical use, information in recent literature on Physalis species pharmacology, and our Native Medicinal Plant Research Program’s recent discovery of 14 new natural products, some of which have potent anti-cancer activity. -

Solanum Pseudocapsicum

Solanum pseudocapsicum COMMON NAME Jerusalem cherry FAMILY Solanaceae AUTHORITY Solanum pseudocapsicum L. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE SOLPSE HABITAT Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. Terrestrial. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe FEATURES Erect, unarmed shrub, glabrous or sometimes with few branched hairs on very young shoots; stems wiry, 40~120cm tall. Petiole to 2cm long, slender. Lamina 3~12 x 1~3cm, lanceolate or elliptic-lanceolate, glossy above; margins usu. undulate; base narrowly attenuate; apex obtuse or acute. Flowers 1~several; peduncle 0~8mm long; pedicels 5~10mm long, erect at fruiting. Calyx 4~5mm long; lobes lanceolate to ovate, slightly accrescent. Corolla approx. 15mm diam., white, glabrous; lobes oblong- ovate to triangular. Anthers 2.5~3mm long. Berry 1.5~2cm diam., globose, glossy, orange to scarlet, long-persistent; stone cells 0. Seeds approx. Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. 3mm diam., suborbicular to reniform or obovoid, rather asymmetric; Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe margin thickened. (-Webb et. al., 1988) SIMILAR TAXA A plant with attractive glossy orange or red berries around 1-2 cm diameter (Department of Conservation 1996). FLOWERING October, November, December, January, February, March, April, May FLOWER COLOURS White, Yellow YEAR NATURALISED 1935 ORIGIN Eastern Sth America ETYMOLOGY solanum: Derivation uncertain - possibly from the Latin word sol, meaning “sun,” referring to its status as a plant of the sun. Another possibility is that the root was solare, meaning “to soothe,” or solamen, meaning “a comfort,” which would refer to the soothing effects of the plant upon ingestion. Reason For Introduction Ornamental Life Cycle Comments Perennial. Dispersal Seed is bird dispersed (Webb et al., 1988; Department of Conservation 1996). -

Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity

Natural Products Chemistry & Research Review Article Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity Morillo M1, Rojas J1, Lequart V2, Lamarti A 3 , Martin P2* 1Faculty of Pharmacy and Bioanalysis, Research Institute, University of Los Andes, Mérida P.C. 5101, Venezuela; 2University Artois, UniLasalle, Unité Transformations & Agroressources – ULR7519, F-62408 Béthune, France; 3Laboratory of Plant Biotechnology, Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tetouan, Morocco ABSTRACT Steroidal alkaloids are secondary metabolites mainly isolated from species of Solanaceae and Liliaceae families that occurs mostly as glycoalkaloids. α-chaconine, α-solanine, solamargine and solasonine are among the steroidal glycoalkaloids commonly isolated from Solanum species. A number of investigations have demonstrated that steroidal glycoalkaloids exhibit a variety of biological and pharmacological activities such as antitumor, teratogenic, antifungal, antiviral, among others. However, these are toxic to many organisms and are generally considered to be defensive allelochemicals. To date, over 200 alkaloids have been isolated from many Solanum species, all of these possess the C27 cholestane skeleton and have been divided into five structural types; solanidine, spirosolanes, solacongestidine, solanocapsine, and jurbidine. In this regard, the steroidal C27 solasodine type alkaloids are considered as significant target of synthetic derivatives and have been investigated -

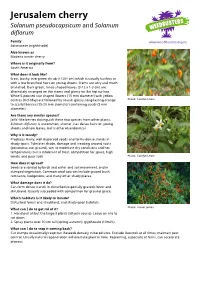

Jerusalem Cherry Solanum Pseudocapsicum and Solanum Diflorum

Jerusalem cherry Solanum pseudocapsicum and Solanum diflorum Family Solanaceae (nightshade) Also known as Madeira winter cherry Where is it originally from? South America What does it look like? Erect, bushy, evergreen shrub (<120+ cm) which is usually hairless or with a few branched hairs on young shoots. Stems are wiry and much branched. Dark green, lance-shaped leaves (3-12 x 1-3 cm) are alternately arranged on the stems and glossy on the top surface. White 5-pointed star shaped flowers (15 mm diameter) with yellow centres (Oct-May) are followed by round, glossy, long-lasting orange Photo: Carolyn Lewis to scarlet berries (15-20 mm diameter) containing seeds (3 mm diameter). Are there any similar species? Jaffa'-like berries distinguish these two species from other plants. Solanum diflorum is uncommon, shorter, has dense hairs on young shoots and new leaves, but is otherwise identical. Why is it weedy? Produces many, well dispersed seeds and forms dense stands in shady spots. Tolerates shade, damage and treading around roots (poisonous, not grazed), wet to moderate dry conditions and hot temperatures but is intolerant of frost, competition for space, high winds, and poor soils. Photo: Carolyn Lewis How does it spread? Seeds are spread by birds and water and soil movement, and in dumped vegetation. Common seed sources include grazed bush remnants, hedgerows, and many other shady places. What damage does it do? Can form dense stands in disturbed (especially grazed) forest and shrubland. Usually succeeded with competition for ground space. Which habitats is it likely to invade? Disturbed forest and shrubland, and shady open habitats. -

2641-3182 08 Catalogo1 Dicotyledoneae4 Pag2641 ONAG

2962 - Simaroubaceae Dicotyledoneae Quassia glabra (Engl.) Noot. = Simaba glabra Engl. SIPARUNACEAE Referencias: Pirani, J. R., 1987. Autores: Hausner, G. & Renner, S. S. Quassia praecox (Hassl.) Noot. = Simaba praecox Hassl. Referencias: Pirani, J. R., 1987. 1 género, 1 especie. Quassia trichilioides (A. St.-Hil.) D. Dietr. = Simaba trichilioides A. St.-Hil. Siparuna Aubl. Referencias: Pirani, J. R., 1987. Número de especies: 1 Siparuna guianensis Aubl. Simaba Aubl. Referencias: Renner, S. S. & Hausner, G., 2005. Número de especies: 3, 1 endémica Arbusto o arbolito. Nativa. 0–600 m. Países: PRY(AMA). Simaba glabra Engl. Ejemplares de referencia: PRY[Hassler, E. 11960 (F, G, GH, Sin.: Quassia glabra (Engl.) Noot., Simaba glabra Engl. K, NY)]. subsp. trijuga Hassl., Simaba glabra Engl. var. emarginata Hassl., Simaba glabra Engl. var. inaequilatera Hassl. Referencias: Basualdo, I. Z. & Soria Rey, N., 2002; Fernández Casas, F. J., 1988; Pirani, J. R., 1987, 2002c; SOLANACEAE Sleumer, H. O., 1953b. Arbusto o árbol. Nativa. 0–500 m. Coordinador: Barboza, G. E. Países: ARG(MIS); PRY(AMA, CAA, CON). Autores: Stehmann, J. R. & Semir, J. (Calibrachoa y Ejemplares de referencia: ARG[Molfino, J. F. s.n. (BA)]; Petunia), Matesevach, M., Barboza, G. E., Spooner, PRY[Hassler, E. 10569 (G, LIL, P)]. D. M., Clausen, A. M. & Peralta, I. E. (Solanum sect. Petota), Barboza, G. E., Matesevach, M. & Simaba glabra Engl. var. emarginata Hassl. = Simaba Mentz, L. A. glabra Engl. Referencias: Pirani, J. R., 1987. 41 géneros, 500 especies, 250 especies endémicas, 7 Simaba glabra Engl. var. inaequilatera Hassl. = Simaba especies introducidas. glabra Engl. Referencias: Pirani, J. R., 1987. Acnistus Schott Número de especies: 1 Simaba glabra Engl. -

An Introduction to Pepino (Solanum Muricatum Aiton)

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-1, Issue-2, July -Aug- 2016] ISSN: 2456-1878 An introduction to Pepino ( Solanum muricatum Aiton): Review S. K. Mahato, S. Gurung, S. Chakravarty, B. Chhetri, T. Khawas Regional Research Station (Hill Zone), Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India Abstract — During the past few decades there has been America, Morocco, Spain, Israel and the highlands of renewed interest in pepino cultivation both in the Andean Kenya, as the pepino is considered a crop with potential for region and in several other countries, as the pepino is diversification of horticultural production (Munoz et al, considered a crop with potential for diversification of 2014). In the United States the fruit is known to have been horticultural production. grown in San Diego before 1889 and in Santa Barbara by It a species of evergreen shrub and vegetative propagated 1897 but now a days, several hundred hectares of the fruit by stem cuttings and esteemed for its edible fruit. Fruits are are grown on a small scale in Hawaii and California. The juicy, scented, mild sweet and colour may be white, cream, plant is grown primarily in Chile, New yellow, maroon, or purplish, sometimes with purple stripes Zealand and Western Australia. In Chile, more than 400 at maturity, whilst the shape may be spherical, conical, hectares are planted in the Longotoma Valley with an heart-shaped or horn-shaped. Apart from its attractive increasing proportion of the harvest being exported. morphological features, the pepino fruit has been attributed Recently, the pepino has been common in markets antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and in Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Chile and grown antitumoral activities. -

Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa Decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives

insects Review Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives Martina Kadoi´cBalaško 1,* , Katarina M. Mikac 2 , Renata Bažok 1 and Darija Lemic 1 1 Department of Agricultural Zoology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.L.) 2 Centre for Sustainable Ecosystem Solutions, School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health, University of Wollongong, Wollongong 2522, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-239-3654 Received: 8 July 2020; Accepted: 22 August 2020; Published: 1 September 2020 Simple Summary: The Colorado potato beetle (CPB) is one of the most important potato pest worldwide. It is native to U.S. but during the 20th century it has dispersed through Europe, Asia and western China. It continues to expand in an east and southeast direction. Damages are caused by larvae and adults. Their feeding on potato plant leaves can cause complete defoliation and lead to a large yield loss. After the long period of using only chemical control measures, the emergence of resistance increased and some new and different methods come to the fore. The main focus of this review is on new approaches to the old CPB control problem. We describe the use of Bacillus thuringiensis and RNA interference (RNAi) as possible solutions for the future in CPB management. RNAi has proven successful in controlling many pests and shows great potential for CPB control. Better understanding of the mechanisms that affect efficiency will enable the development of this technology and boost potential of RNAi to become part of integrated plant protection in the future. -

Pepino (Solanum Muricatum Ait.): a Potential Future Crop for Subtropics

ISSN (E): 2349 – 1183 ISSN (P): 2349 – 9265 4(3): 514–517, 2017 DOI: 10.22271/tpr.201 7.v4.i3 .067 Mini review Pepino (Solanum muricatum Ait.): A potential future crop for subtropics Ashok Kumar*, Tarun Adak and S. Rajan ICAR-Central Institute for Subtropical Horticulture, Rehman Khera, P.O. Kakori, Lucknow-226101, Uttar Pradesh, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] [Accepted: 26 December 2017] Abstract: Pepino (Solanum muricatum) is an Andean region’s crop, originated from South America. The crop has medicinal values and underutilized for its cultivation. It has a wider adaptability across the different locations of Spain, New Zealand, Turkey, Israel, USA, Japan etc. The crop can be grown under diverse soil and climatic conditions in India also. Its fruits are juicy, mild-sweet, sub-acidic and aromatic berry which are rich in antiglycative, antioxidant, dietary fibres and low calorific energy. Fruit is visually attractive with golden yellow colour with purple stripes. The crop was evaluated for its growth and development at ICAR-Central Institute for Subtropical Horticulture, Rehmankhera, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India (planted in the month of October, 2014). The results of the study exhibited its adaptation to climatic conditions of subtropics with higher yield and acceptable fruit quality. Keywords: Solanum muricatum - Pepino - Subtropic - Adaptation. [Cite as: Kumar A, Adak T & Rajan S (2017) Pepino (Solanum muricatum Ait.): A potential future crop for subtropics. Tropical Plant Research 4(3): 514–517] INTRODUCTION Introduced crops have a vital role in the progress of mankind; on any region of the world, many most important crops did not originate there but were new crops at the time of their introduction. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Solanaceae

TAXON 57 (4) • November 2008: 1159–1181 Olmstead & al. • Molecular phylogeny of Solanaceae MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS A molecular phylogeny of the Solanaceae Richard G. Olmstead1*, Lynn Bohs2, Hala Abdel Migid1,3, Eugenio Santiago-Valentin1,4, Vicente F. Garcia1,5 & Sarah M. Collier1,6 1 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, U.S.A. *olmstead@ u.washington.edu (author for correspondence) 2 Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, U.S.A. 3 Present address: Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt 4 Present address: Jardin Botanico de Puerto Rico, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Apartado Postal 364984, San Juan 00936, Puerto Rico 5 Present address: Department of Integrative Biology, 3060 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, U.S.A. 6 Present address: Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, U.S.A. A phylogeny of Solanaceae is presented based on the chloroplast DNA regions ndhF and trnLF. With 89 genera and 190 species included, this represents a nearly comprehensive genus-level sampling and provides a framework phylogeny for the entire family that helps integrate many previously-published phylogenetic studies within So- lanaceae. The four genera comprising the family Goetzeaceae and the monotypic families Duckeodendraceae, Nolanaceae, and Sclerophylaceae, often recognized in traditional classifications, are shown to be included in Solanaceae. The current results corroborate previous studies that identify a monophyletic subfamily Solanoideae and the more inclusive “x = 12” clade, which includes Nicotiana and the Australian tribe Anthocercideae. These results also provide greater resolution among lineages within Solanoideae, confirming Jaltomata as sister to Solanum and identifying a clade comprised primarily of tribes Capsiceae (Capsicum and Lycianthes) and Physaleae. -

Solanum Macranthum M.F. Dunal Brazilian Potato Tree

Solanum macranthum M.F. Dunal Brazilian Potato Tree (Solanum crinitum, Solanum wrightii) • This species is also known as Blue Potato Vine, Giant Potato Tree or Giant Star Potato Tree; a tropical evergreen large shrub to small tree in USDA hardiness zones 9b to 13 reaching 8 to 15 (20) tall, S. macranthum also serves as a herbaceous perennial in zone 9a; this South American species can be grown as a summer annual in colder climates; initially plants are erect in habit, becoming more rounded at maturity; the texture is decidedly coarse. • Stout clubby stems are mostly hidden by the large, 8 to 12 long, ovate leaves with prominent pointed pinnate lobing, creating an overall resemblance to large oak leaves; leaves are a dark rich lustrous green with hirsute pubescence which is most prevalent beneath; stout petioles and stems also have stiff yellowish pubescence; frequently yellowish prickles are found on the stems or underside of the main veins, although a prickleless form is sometimes encountered under the cultivar name of 'Thornless'; bark is initially green, becoming splotched brown over time, then eventually the smooth gray brown bark develops very shallow cracked plates, appearing almost corky on older trees. • Clusters of attractive five-pointed star-shaped flowers appear at the margins of the canopy where they are highly visible; petals overlap and are lightly ruffled on the margins with vertically protruding central yellow anthers; the specific epithet means large anthers; flowers mature through color changes from lavender, violet, or purple progressively fading to lighter tints until individual flowers turn white before senescing; this results in a multiple flowers in the bluish purple to white ranges present together at any one time; flowering occurs whenever temperatures permit; pendent fruits resemble small green tomatoes with dark splotches and are not ornamental; flowers attract bees and butterflies. -

The Fruit Leaf C Santa Clara Valley Chapter

are Frui ia R t G rn ro fo w i l e a r s The Fruit Leaf C Santa Clara Valley Chapter y S nt an ou California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc. ta Clara C March/April http:/www.crfg.org 2009 Inside this issue Next Meeting Next Meeting ...........1 Edible Landscaping ..2 April 11, 2009 Emma Prusch Park Pitaya Festival ...........3 Social and set-up 12:30 p.m. Pepino Dulce ............4 Meeting 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. Events .......................5 Anatomy ..................6 Speaker for Avocados First Hand Experience Growing Them in the Bay Area Prusch Work Days ...7 By Jack Kay Contacts ...................8 For our April meeting, we are fortunate to have Gene Lester speak to our chapter. Many of you are familiar with Gene’s tremendous citrus collection that he grows on his property in the hills above Watsonville. Gene also has what may be the most extensive non-commercial collection of avocados trees in the bay area growing on his property. He will present to us information on this collection and Membership: what he has learned up to now growing this fruit. For information on chapter membership, notification of address and phone number changes, please contact: April Meeting Sarah Sherfy, Green Scion Exchange, 9140 Paseo Tranquillo, It is up to each individual member to make the April 11, Green Scion Gilroy CA 95020. 408 846-5373 exchange a success! What is a green scion? Well, it is material from [email protected] plants that do not go dormant in the winter. This includes plants such as citrus, avocado, guava, fejoa, sapote, loquat, Surinam cherry, etc.